How can we afford not to?

Last week’s public post argued that Australia’s federal government should avoid falling into the trap of engaging in large-scale industrial policy. I thought it was relatively comprehensive, but then Anthony Albanese promptly went ahead and announced new legislation called the Future Made In Australia Act, which while still very light on details (how can you speak over 3,000 words and still not convey much useful information?) looks like it will, when formalised, contain the plan for his government’s “new approach” to industrial policy.

We’re exactly one month out from the Budget – potentially the last ’normal’ Budget before next year’s election – and fewer than 200 days before Queensland’s state election (which is where Albo delivered his manifesto), so the timing makes sense. Albo wants to paint his government as builders; as job creators, and as “a participant, a partner, an investor and enabler”, rather than “an observer or a spectator”. According to Albo, his approach “will be guided by three principles” (I’ve trimmed it down slightly because it’s long, but it’s all from his speech):

“First, we need to act and invest at scale.

Moving beyond a ‘hope for the best’ approach where the priority has been minimising government risk, rather than seeking to maximise national reward.

Second, we need to be more assertive in capitalising on our comparative advantages and building sovereign capability in areas of national interest.

For too long, Governments have taken a reactive, patchwork approach which has been more about managing an immediate crisis rather than maximising long term opportunity.

…

Thirdly, we will continue to strengthen and invest in the foundations of economic success.

…

We recognise that for Australians to fully share in the rewards, Government needs to be prepared to use its size and strength and strategic capacity to absorb some of the risk.

Only Government has the resources to do that.

Only Government can draw together the threads from across the economy and around our nation.

To anchor this reform and secure this growth, today I announce that this year our Government will create the Future Made in Australia Act.”

To do that, Albo will create “government investment funds”, leverage “our national superannuation system” (somehow), and use a “combination of financing facilities and investor incentives”. I suspect a lot of this has already been done, in some form or another – think Hydrogen Headstart, Critical Minerals Facility, National Reconstruction Fund, Net Zero Economy Authority, Powering the Regions Fund, and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation. Together those programs already have government funding to the tune of over $50 billion, which is significant – about ten times as much as the government is spending on “strengthening Medicare” over the next five years. No doubt the Future Made in Australia Act will see even more government bodies created, and even more subsidies doled out to favoured firms.

But what is a bunch of industrial policy without a catchy name? A Future Made in Australia is clearly Albo’s version of Trump’s Make America Great Again, or Biden’s Build Back Better. Because these days, every politician needs a slogan within which to wrap their propaganda.

Albo, man of system

And that’s all a Future Made in Australia is: propaganda. Albo is trying to take us back to the days when government was less of a referee and more of an active player in the economy; to the days before the Washington Consensus, which he says “has fractured”.

But the times for which Albo pines were not good times, comparatively speaking. He’s taking this country away from what we know works, i.e. setting and enforcing the rules of the game and then letting the capitalists duke it out, and back towards what we know doesn’t work, namely government as economic referee and player. Rather than focusing on improving the simple tried and true, Albo is doubling down on the failed policies of economists and politicians long since discredited and discarded. In doing so, Albo fully embodies Keynes’ “practical man”:

“Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

But he’s also Smith’s man of system:

“The man of system… is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it. He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess–board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess–board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess–board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it.”

Albo and Treasurer Chalmers, given their fondness for industrial policy, are the last people you would want in charge of such a policy. As Larry Summers recently warned:

“Look, I think this is something we need to think very hard about. I believe that the best generals are the ones who hate wars most, and I believe the best industrial policy experts are the ones who hate it most. The problem is that the only people who talk about industrial policy are the ones who love it and are looking for a reason to do it. Anyone who can… talk for five minutes about why we need industrial strategy or resilience without saying the words “it will create US jobs” I have substantial time for but whenever it comes with a whole set of talk about US jobs then it becomes much more problematic.”

Albo mentioned jobs 9 times in his speech, and listed desired outcomes from “promoting gender equality” to “fairer wages”. Those are noble goals, but for industrial policy to even have a chance at success then it should only focus on achieving what arguably can’t be done through market forces, such as national security. Trying to target any other outcome is a distraction that will undermine that goal.

Worse, Albo risks creating a path dependent, self-reinforcing outcome where concentrated special interests capture the political process, making it extremely difficult to unwind subsidies and protection when the investments fail to produce a return. Politicians simply can’t help themselves once there are jobs to be lost, businesses that could be shut down, or towns that could disappear. This really is a gift that could keep on giving, in the form of higher prices, for many decades to come.

The wrong way to do industrial policy

I have no objection to goods being made in Australia. I have no problem with helping industry. But there’s an economically efficient way of doing that, and then there’s a Future Made in Australia.

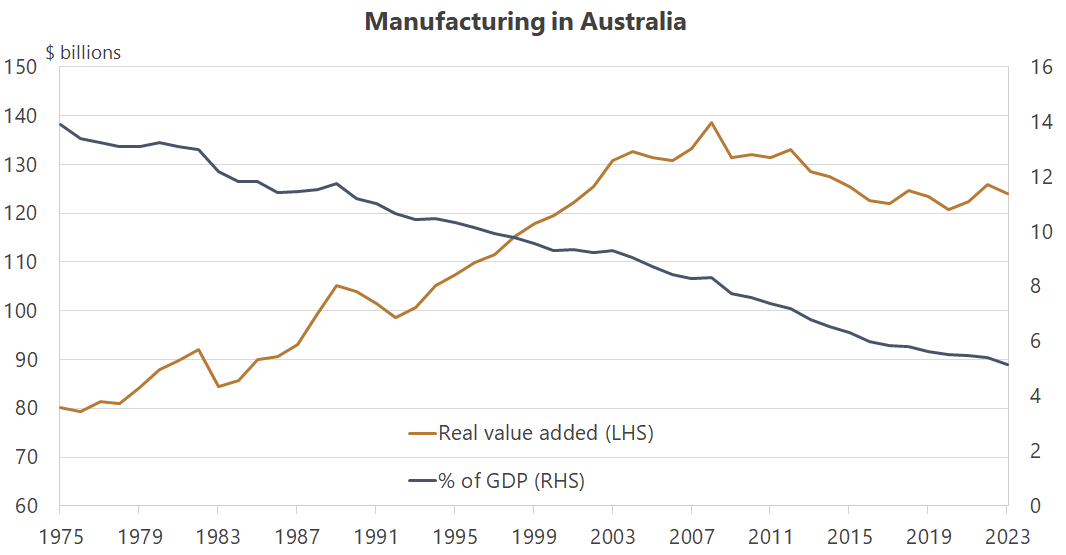

Believe it or not but we still manufacture a lot in Australia, despite its share of GDP falling steadily over time.

That’s for two reasons: one, productivity has improved. Our manufacturing industry is a lot more sophisticated and productive than it was in 1975, so we can now produce a lot more with less, which means we need fewer workers and a relatively smaller manufacturing sector.

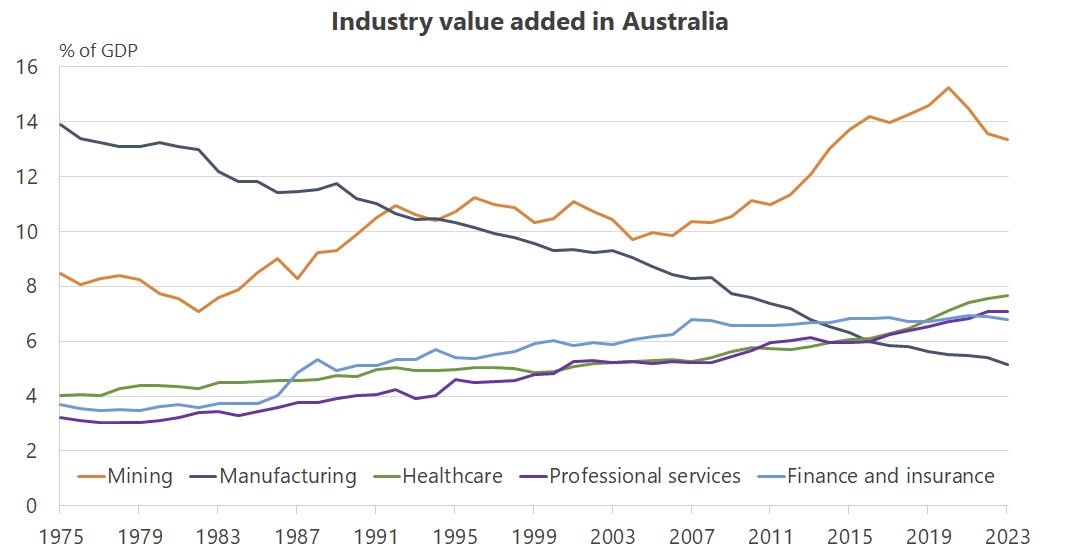

Two, manufacturing competes for scarce resources with even more productive industries, such as mining. As manufacturing became relatively less profitable – especially after the mining booms following the Great Recession in 2008 – people and capital shifted to higher value-added sectors, allowing our economy to more effectively grow and compete with the rest of the world.

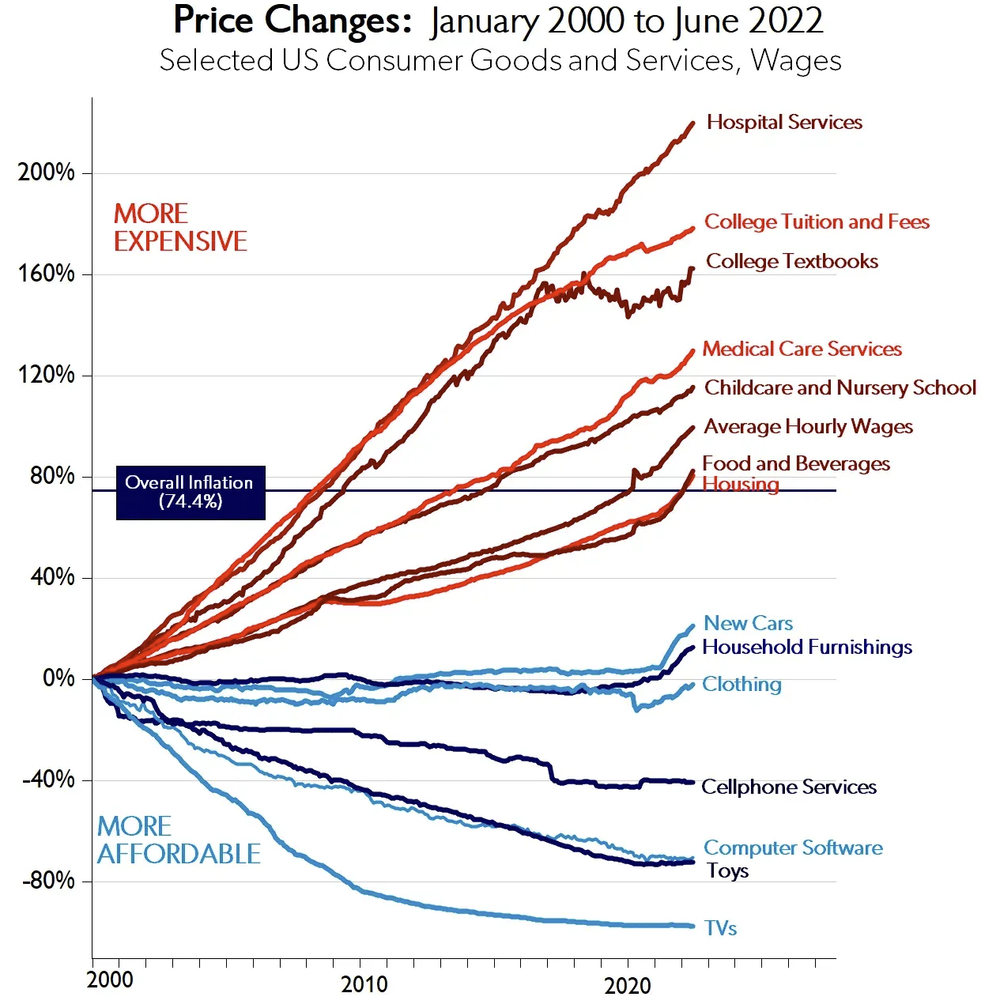

Not all of the sectors that have grown are more productive than manufacturing. Healthcare, for example, is clearly not – it’s very labour intensive, and a nurse is not that much more productive than they were 50 years ago. But that’s just the nature of Baumol’s cost disease: sure, we could all work in mining and IT, but then who would pour our coffee, play for your local AFL club, or care for your grandparents? Wages have to rise in the less productive sectors so that people will keep performing those services we value as consumers. You may have seen this chart, which is for the US but also applies in Australia (housing would be much more expensive in the Australian version!).

In Australia, our golden productivity goose is the mining sector. Our government’s books would look considerably worse without the constant stream of royalties and corporate taxes that flow directly from it. Without mining, we would have a more diverse economy – including more manufacturing – but we would be poorer as a nation, with a lower standard of living. Certain luxuries we now consider “essential” would simply be unaffordable.

Importantly, you can’t just allocate additional resources into manufacturing, as Albo wants to do, and change this fact. We could make more solar panels in Australia, sure, but that means less of something else – maybe healthcare or education. We pay for our consumption of these services with productivity elsewhere, and there’s always an opportunity cost: by allocating more resources from higher to lower productive uses, such as from Chinese solar panels to Australian solar panels, we can’t have as much of something else.

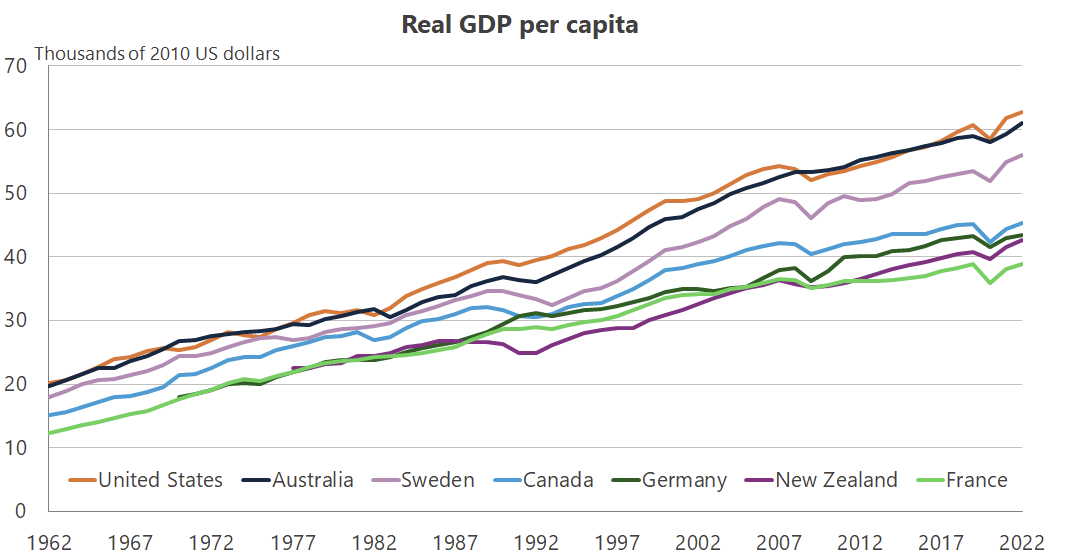

Productivity is everything

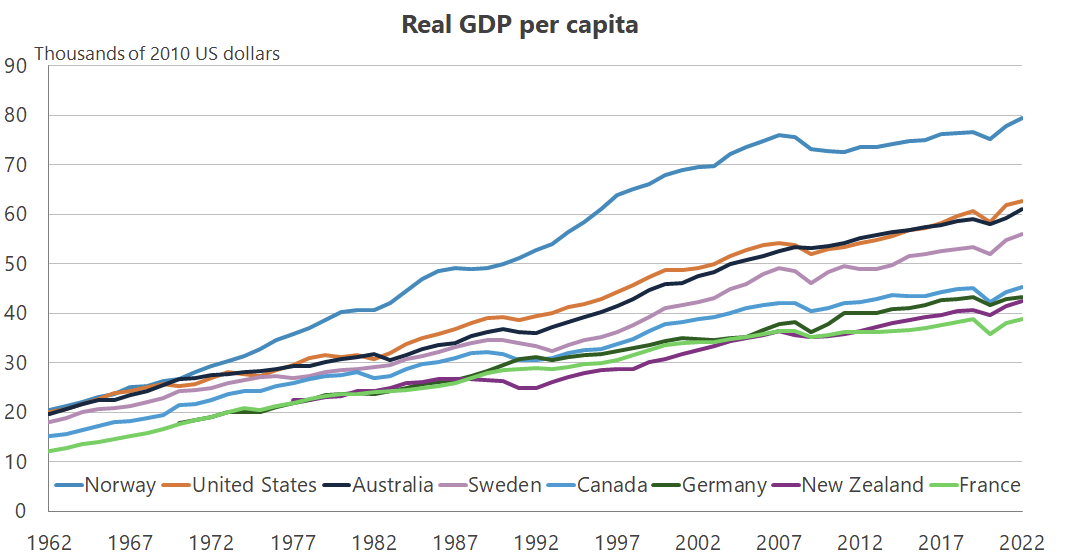

Australia has done comparatively well because we were fortunate enough to be blessed with many of the world’s most sought-after commodities, but also because our governments trusted a lot to Albo’s much-derided “invisible hand”. Today, our real GDP per capita is right up there with the US and is well ahead of other advanced nations, thanks in no small part to a hugely productive mining sector.

But it could be better; we could have been Norway, had we managed our mineral wealth more appropriately. Like Australia, Norway is commodity-rich, almost entirely from oil. But instead of spending and borrowing against the windfall, as our governments have done in Australia, the Norwegian government had the foresight to run budget surpluses and set up a sovereign wealth fund to pay for future obligations, with fiscal rules linked to the fund’s expected returns preventing the government from draining it prematurely.

Norway’s fund has now banked around A$450k per citizen. Obviously it’s too late for us to do similarly; unlike Norway where fiscal surpluses are the name of the game, all levels of Australian government are heavily indebted and running deficits. We’re also paying over 4% on that debt, while Norway’s fund returns a long-run net annual real return of 3.8%, so it makes zero sense to “save” anything – we’d be better off just paying off our debt.

How can we afford not to?

Australia has a huge opportunity. We can avoid a self-defeating spiral into industrial policy but still benefit from our trading partners’ foray into that wasteful realm by buying their subsidised goods – the closest thing we’ll get to a free lunch. Or we can join them, with our tiny domestic market that makes it virtually impossible to compete at scale, diversifying ourselves into relative poverty. When asked whether Australia can compete with China in producing solar panels, Albo said:

“It’s not whether we produce solar panels, it’s how can we afford not to? How can we be dependent – when one in three Australian households have solar panels on their roofs – not to have some national resilience here?”

Albo doesn’t realise it, but he answered his own question: we’re already dependent on China for solar panels! From where does he think the 33% of Australians who already have them, got them? Just how we don’t make cars, washing machines, pyjamas, ballpoint pens or toasters in this country anymore, we don’t need to manufacture solar panels, windmills or green steel. We can sell something else and trade for them (economists call this comparative advantage). If not from China, then Malaysia or Vietnam, although barring a major war it’s not clear why China wouldn’t want to continue exporting solar panels, given its own industrial policy has left it with considerable excess capacity.

Contra Albo, the time to diversify our economy is when it’s profitable to do so and not a day sooner. Governments should ensure their balance sheets are healthy enough to help facilitate such a transition (the Norway model), should it happen relatively rapidly – always a possibility in a country with a large mining sector that’s dependent on volatile commodity prices. But moving early risks wasting resources that could be better used elsewhere.

Incentives and opportunity costs

The IMF, seeing the turn towards industrial policy and protectionism, recently warned that:

“Industrial policies targeted to specific sectors, if poorly designed, may impede resource allocation to more productive firms or sectors… To lessen the negative growth impact from increased geoeconomic fragmentation, it is important to steer clear of damaging unilateral trade and industrial policies.”

Politicians are not omniscient. Albo and the bureaucrats he instructs to execute his Future Made in Australia have information issues and their own set of incentives. Those constraints will make it very difficult for them to find investment opportunities that create benefits exceeding costs, given that people risking their own money have not been able to.

Sure, Albo could avoid that by only picking ‘winners’, but then the question becomes why? Are Australians incapable of adjusting to changing demand, from shifting from older industries to the ones at the forefront of the new energy transition? Not likely. And unlike those investing their own money, Albo and his bureaucrats face very little cost if they make the wrong decisions – perhaps only their prorated share of lost tax revenues, which is likely more than offset by the pay and prestige they get from running these programs.

Further, Albo’s Future Made in Australia will raise prices and reduce the amount of capital available for unsubsidised entrepreneurs. We will, by definition, be producing less output using more resources. And any “jobs” created will come from those other, unsubsidised firms, not the unemployed, given we’re at full employment and have well-publicised skills shortages. According to the Productivity Commission’s Danielle Wood:

If we are supporting industries that don’t have a long-term competitive advantage, that can be an ongoing cost. It diverts resources, that’s workers and capital, away from other parts of the economy where they might generate high value uses.

We risk creating a class of businesses that is reliant on government subsidies, and that can be very effective in coming back for more."

Australia has a small, open economy. We cannot afford to go down the road of industrial policy, even if some of our allies are doing so. International trade and the rule of comparative advantage is especially important to small countries like ours, because they give us access to economies of scale that are not available domestically.

Instead of industrial policy, we should be supporting industry by eliminating our remaining trade barriers, relaxing occupational licensing laws, breaking down the NIMBYs and their zoning restrictions so people can move to where the jobs are at, and start thinking in terms of trade-offs.

It may sound boring but we know it works, unlike Albo’s Future Made in Australia, which – other than for a few well-connected businesses and workers – will make us all worse off.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!