How to lose a state election

The next Western Australian state election will be held on the 8th of March, or a little over three weeks from now. It’s a general rule of mine that as an election approaches, the policy announcements will tend to get worse as each party tries to outdo each other in a race to win over the median voter.

Enter the governing WA Labor party, which—clearly inspired by the recent big spending state election in Queensland— has proposed to cap public transport fares:

“Public transport fares would drop to a flat fee of $2.80 for SmartRider holders under a one-zone system WA Labor is promising to roll out if re-elected.

If it wins a third term in the March state election, Labor has pledged to abolish the nine-zone transport system and introduce the flat fare across the entire public transport network.

…

[WA Premier] Mr Cook would not be drawn on whether WA fares could be dropped further.”

All I can say is at least they’re not dropping fares to 50 cents, as was just done by the Queensland Liberal Party.

Anyway, here’s how WA Treasurer Saffioti justified the new subsidy:

“We know from a cost of living perspective, public transport is a great economical way to move around our suburbs.

It connects people to jobs and opportunities, it connects people to education institutions.

And for those who can’t use public transport — because they might be tradies going to a job site — it takes cars off roads.”

All of that is true because Saffioti is defining public transport generally, not her party’s policy of capping fares well below the true cost of providing the services.

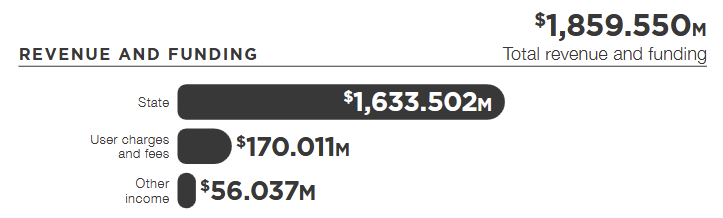

And those costs are significant. In the last financial year, the Western Australian Public Transport Authority received a subsidy of more than $1.6 billion, or around $550 per resident in the state:

Most people in the state don’t use the public transport network. Of those that do, they received an effective subsidy that averaged $11 per trip. That’s a lot of coin to be spending on something that a private network of buses would be able to achieve at a much lower cost to the taxpayer!

Is Western Australia’s public transport network nicer – ‘gold plated’, if you will – than a hypothetical bus-dominant alternative? Of course; people like Perth’s ever-expanding network of trains, even if they make little economic sense in one of the least dense cities in the world.

In fact, that’s the reason why I titled this essay How to lose an election: I know that what I’m writing would quickly make me the most unpopular person in Perth if it was proposed as policy!

But someone has to say it, and it’s my view that using heavily subsidised trains to connect Perth’s seemingly endless sprawl of low density suburbs must be the most costly, wasteful way to build a transport network. METRONET – not an acronym, despite the capital letters – will surely go down in history as one of the worst examples of boom-time largess, saddling the people of Western Australia with debt that will take many decades to repay.

But there is a way to fix it.

Two wrongs don’t make a right

Go to the top comment of just about any social media post discussing the perks of Perth and there’s a good chance it will look something like this:

One reason Treasurer Saffioti wants to “take cars off roads” through public transport subsidies is because the Western Australian government doesn’t charge people for using its roads, so the quantity demanded is too high and you end up with this:

“A new RAC survey released on Friday shows that 80 per cent of drivers believe Perth roads have become more congested in the past year.

Three-quarters of drivers say they have seen an increase in road rage and driver frustration as the traffic backed up — 10 per cent worse than 2023’s survey.

It comes as congestion and traffic firms as a State election issue, with the major political parties vowing to throw millions of dollars at the worst hot spots.”

By having “free” roads, externalities such as pollution and traffic proliferate, and if the government did nothing about it they would soon lose office. But rather than addressing the pricing problem directly and risk upsetting a vocal subset of voters who have become accustomed to “free” stuff, their prerogative is to just throw money at the inefficient overbuilding of capacity to meet the artificially high demand.

But there’s a problem with that plan. After a short period of time, a phenomenon known as induced demand kicks in. Basically, as people notice the roads getting less busy due to drivers substituting their cars for cheaper public transport, the roads gradually become just as congested as they were before.

Rinse, repeat.

Now before you jump down my throat about roads not being “free”, I’m well aware that drivers technically pay for the roads via the federal fuel excise tax. But only 57 cents on the dollar of that actually goes back into transport infrastructure, and more importantly it doesn’t fully account for when or what you drive.

For example, big trucks pollute more and cause greater damage to roads than small commuter vehicles. Conversely, small vehicles driving during the busiest times of the day cause significant costs in the form of road congestion.

The first-best way of dealing with the many externalities associated with “free” roads is to put a price on them. For example, say you wanted to build a new bypass to alleviate congestion on a highway that, because of urban sprawl, now runs through a residential area. Rather than have taxpayers fork out the original cost plus an extra 70% (because such projects always seem to find a way to run over budget), why not pay for it with a toll?

There’s no economic or equity case not to: the benefits are concentrated among the road’s users, so they should really be the ones paying for it.

But don’t screw it up

However, execution is key. What you don’t want to do is end up like Sydney, where the government transferred the monopoly rights for its toll roads to private parties in exchange for some quick cash.

Instead, look to places like Singapore, where the government has been using fully automatic, variable prices for nearly 30 years. Or France, where highways are privately managed (government owned) but the operator is responsible for upkeep, modernisation, and safety. The private operator charges tolls with prices regulated using a model that should be familiar to Australians, as it’s how we manage natural monopolies from electricity to rail.

My point is there are lots of viable models out there, but the key is to ensure that the cost of constructing and maintaining transport infrastructure is shared among those who use it.

Unfortunately, the political incentives in Western Australia are always for overbuilding rather than proper pricing. Thanks to the 75% GST floor deal and rock-solid commodity prices and volumes, the state is rolling in royalty revenue. If it whacked tolls on its highways, 25% of any revenue collected would flow straight to claimant states like Tasmania.

That’s a hard sell to taxpayers in Western Australia, and if you combine it with the fact that state politicians generally aren’t the sharpest knives in the drawer, it means Canberra – which currently pays at least half of any significant road network upgrade – is the entity that would have to put the squeeze on them for anything to change.

And Canberra will be aware of that – one of its key independent advisors recently recommended as much:

“Infrastructure Australia says the Government should use the ‘power lever’ of the GST distribution to drive state governments into adopting policies the organisation believes will drive economic growth.

Top of its list is the introduction of ‘road user charging’ — congestion charges in inner-city areas and road tolls for major freight transit routes.

‘Australia’s level of vertical fiscal imbalance provides the Australian Government with a powerful lever to drive national change, particularly when funding is tied to specific conditions,’ the report says.

‘Despite a recent increase in tied funding, states and territories have discretion over how they spend the majority of funding provided by the Australian Government’.”

Our states need a solid injection of common sense and fiscal discipline, and strong-arming them by threatening to withhold funding or offering incentive payments is probably the best way to achieve that.

Congestion pricing is also needed

On top of raising the price of public transport so that it more accurately reflects its costs, and whacking tolls on major highways, Western Australia also needs congestion pricing to control the mess that is the City of Perth’s rush hour traffic.

Like the other two ideas, congestion pricing would see users of the roads pay a price that reflects the full social cost of their trip, rather than being subsidised by non-users. Those best placed to find alternatives (e.g. travel at different times, use public transport, work from home) would do so, helping to control the congestion and pollution externalities associated with roads. Moreover, the funds raised could be used to improve infrastructure or reduce other distortionary taxes.

But one problem with congestion pricing, as with tolls and properly priced public transport, is it’s deeply unpopular with the electorate:

“[M]ore than half of New York State voters who responded to a Siena College survey released in December opposed it [congestion pricing]. Some opponents have continued to fight the program in court. President Trump has said he will kill the program and Gov. Philip D. Murphy of New Jersey recently wrote the president a letter urging him to act.”

That’s from New York, which recently imposed a congestion toll of $9 to enter a new “congestion relief zone” in Manhattan. While that’s not the best way to price roads – you really want a dynamic price that adjusts based on traffic so that you ’nudge’ people to shift non-commute trips to other times of the day or onto different routes – the effects were instant:

“A report this week from the MTA also showed significant drops in travel times, including 30-40 per cent for vehicles entering Manhattan’s business district. It also found that city buses were moving faster and that their ridership was slightly higher.

According to the Congestion Pricing Tracker, a project by college student brothers Benjamin and Joshua Moshes that monitors commute times via Google Maps, peak times through the Holland Tunnel fell from 20 minutes pre-toll to nine minutes this week.”

Shocking, right? When the price of driving increases, fewer people drive. And New York’s congestion toll, now that it has been in place for several weeks, has quickly grown in popularity to the extent that a majority support its continuation.

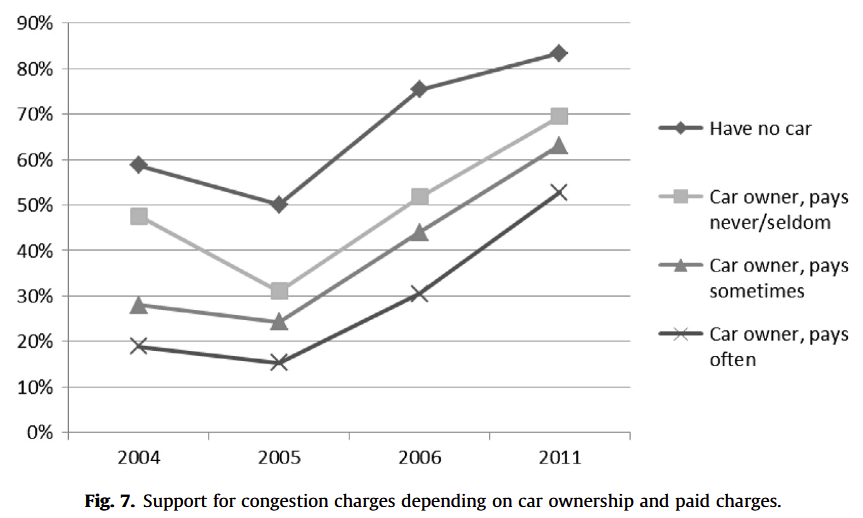

That’s consistent with the academic literature, which shows that “public support for congestion charges increase substantially after charges have been introduced”:

“At the beginning, there is little or no public support for road pricing. Support increases with the recognition for a problem of congestion, environmental damage, or adverse effects of traffic on quality of life. Sufficient public support leads to the development of detailed plans and schemes. This generally results in a fall-off of public support and can lead to rejection of the policy. Support builds up again once the scheme has been implemented and the benefits are recognised.”

Or in chart form, showing the real experience from Stockholm (2005 was the year before the pilot went into effect):

To sum up, instead of expanding highways and building rail lines that subsidise urban sprawl, the Western Australian government just needs to fix its own policies that prevent prices from doing their job. As an added bonus, road pricing would also improve the relative appeal and competitiveness of METRONET, allowing the state government to raise prices and offset some of the billions of dollars it loses each year on operational costs alone.

But ultimately, none of what I’ve written matters because the median voter seems to love heavily subsidised public transport, i.e. having their bus and train rides paid for by tradies, those out in the regions, and anyone else who doesn’t or can’t use the network.

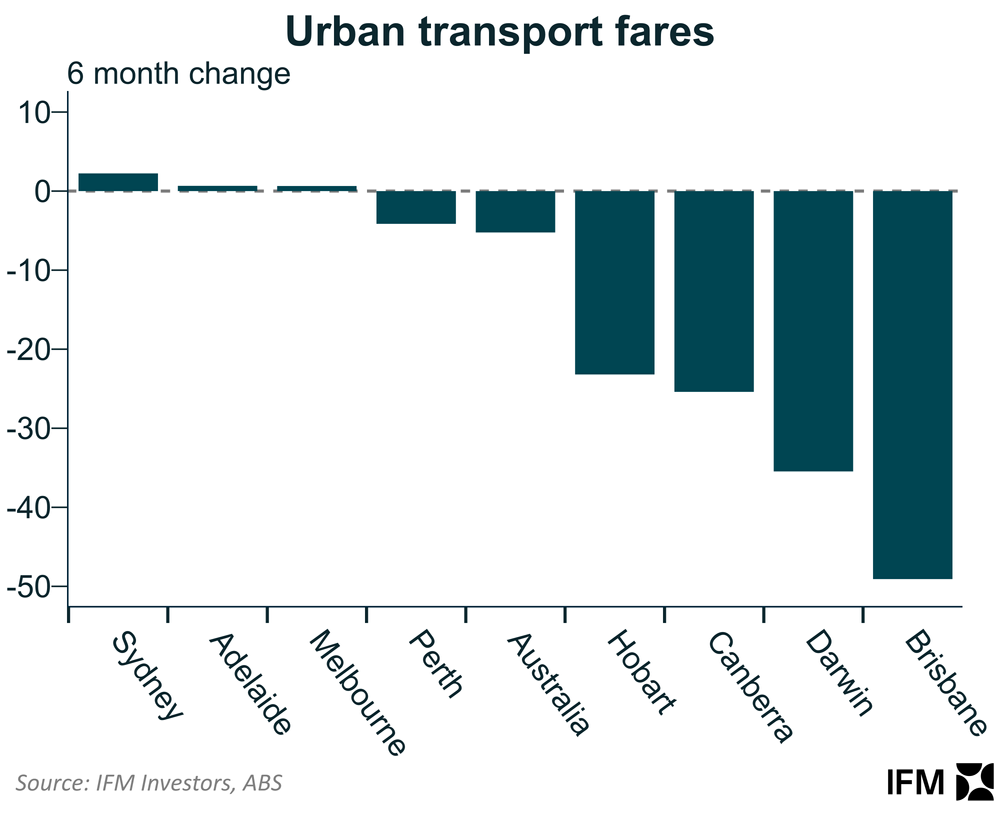

WA Labor will win the March election, and the subsidy for road and public transport users will grow even larger. The same pattern can be observed in just about every jurisdiction in Australia, with prices either frozen well below inflation or being cut outright:

As artificially cheap public transport becomes engrained in the nation’s culture, it effectively becomes an entitlement. And good luck to any future government that is forced to consider raising prices when the inflationary-driven revenue gravy train stops running!

All I have left to say is it’s a good thing I’m not running for political office, because in the race to spend other people’s money on bad policies, I’d come in dead last.

We get the congestion we deserve.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!