Ignore the doomsayers on real wages

Earlier this week the Productivity Commission (PC) released its latest report examining Australia’s “labour productivity over the COVID-19 pandemic”.

It’s a good read, and basically confirms what I’ve been saying for a long time—namely, that real wages in Australia had to fall because they were artificially high to begin with. Essentially, we were in a productivity bubble:

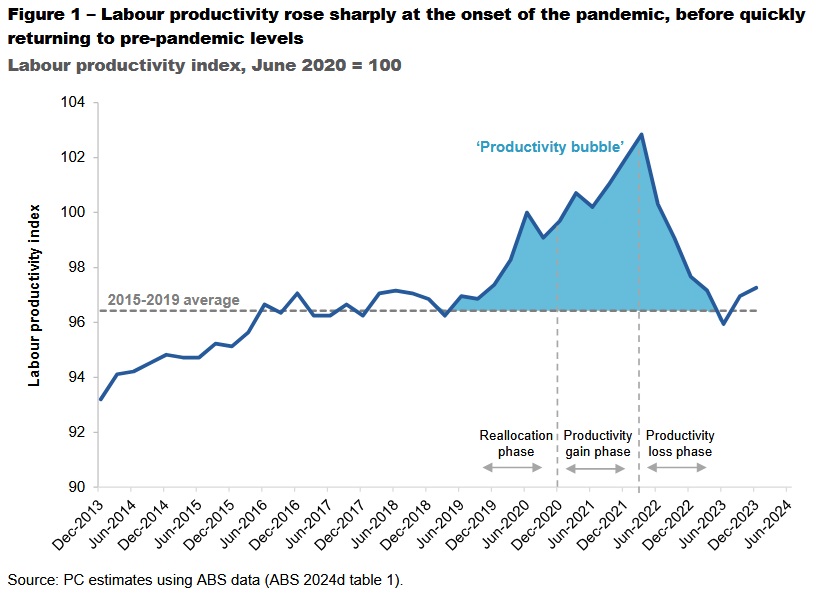

“In Australia, a peculiar pattern in labour productivity – a labour productivity bubble – emerged during the pandemic. Labour productivity rose to a record high from the onset of the pandemic in January 2020 to March 2022 before declining and returning to its pre-pandemic level in June 2023. This bubble can be divided into three phases which this paper seeks to explain.

• A ‘reallocation’ phase – the initial phase, between December 2019 and December 2020, where labour productivity rose as lockdowns were most severe, economic activity was curtailed, and labour was reallocated away from disrupted industries.

• A ‘productivity gain’ phase – the second phase, between December 2020 and March 2022, where labour productivity continued to rise as lockdowns eased and economic activity slowly rebounded.

• A ‘productivity loss’ phase – the third phase, between March 2022 and June 2023, where labour productivity declined rapidly and returned to its December 2019 level.”

Here’s the chart:

The PC didn’t get into wages at all, but given that productivity is what drives real wages, I think the idea of a productivity bubble has useful insights there, too.

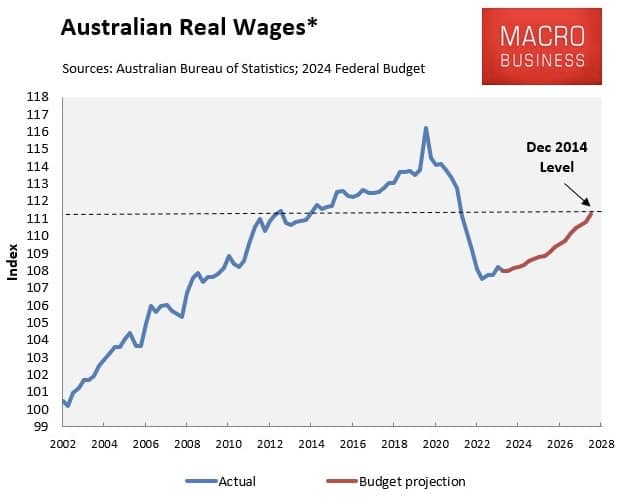

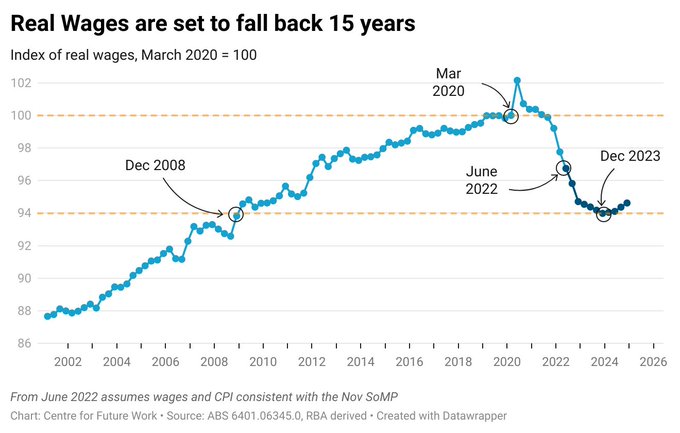

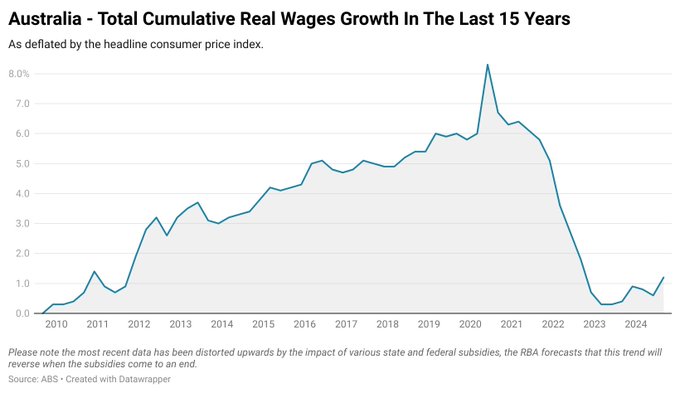

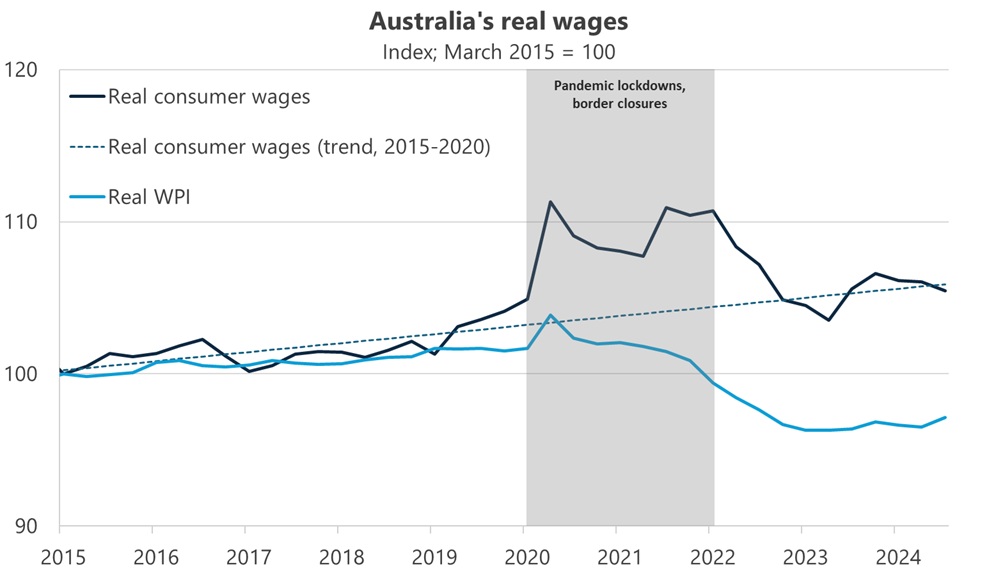

For example, you may have heard of Australia’s ‘cost of living crisis’, which is directly related to the large decline in Australia’s measured real wages. Charts like these have been trotted out as justification over the past few years by think tanks, journalists, and even sitting senators, all of whom have their own pet policy response:

All of those charts measure real wages by deflating the wage price index (WPI) with the consumer price index (CPI). Now, most of the time that’s perfectly fine. But during periods of rapid change, like we experienced with labour productivity during the pandemic, it can lead you astray.

Why? Because the WPI is not actually a measure of people’s wages but a measure of wages for specific jobs. That means it can miss changes in wages from people changing job titles or roles, and so tends to lag reality when reality is moving quickly.

Then there’s the CPI, which is also flawed in certain situations: it only captures pure price changes, not substitution effects or changes in the composition of household expenditure—both of which were happening rapidly during the pandemic! That means it can easily over- or under-estimate how much people’s costs have really changed during periods of rapid adjustments in the composition of household spending.

Put them together, and folks trotting out charts like the ones above are probably overestimating Australia’s real wage decline and the ‘cost of living crisis’.

Thankfully, there is another way! My preferred measure of real wages is what’s known as consumer wages. They’re calculated by deflating total non-farm compensation per hour worked by household final consumption expenditure—essentially, taking wages and salaries plus employers’ social contributions and dividing it by what households actually spend it on.

Looking at consumer wages shows that Australian households experienced a pandemic-induced real wage bubble, in-line with the productivity bubble: a big rise, then back to somewhere slightly above pre-pandemic levels. Here I’ve plotted it against the WPI/CPI method used above to show the difference between the two indicators:

As you can see, real consumer wages are almost exactly where they would have been if the 2015-2020 trend had continued—which is also what the PC found happened to productivity:

“The eventual return to the long term trend, as opposed to productivity remaining higher, appears to have been driven by the flow of workers back into lower-productive industries, a slowing capital-to-labour ratio and a decline in the average skills and experience of the workforce as new workers joined the labour force.”

These data suggest that Australia’s cost of living crisis has likely been overblown. However, real wages simply returning to the long-run trend “is not a cause for celebration”. Australia’s productivity growth is still in the gutter—and has been for more than a decade—so our governments must respond proactively if we ever want to see real wages moving sustainably higher again, i.e., without driving up unemployment by coercively setting wages higher than labour productivity.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!