Inching towards affordable housing

I’ve got some good news: we’re making progress on housing affordability! It won’t show up in the data immediately, but already this year a couple of state governments have announced steps that will increase housing supply:

- From 1 April 2024, the NSW government will allow apartments to be built in all residential zones (R1, R2, R3 and R4) and shop top housing in local and commercial centres (E1 and E2) within 400m of metro and rail stations.

- From mid-April, the WA government will abolish planning approval requirements for granny flats up to 70sqm in any residential zone, and will remove the requirement for an extra car bay. I’ve previously written about why this would be a great start to improving affordability.

- As part of its ongoing zoning reforms, the SA government approved medium density zoning code amendments on vacant land around metropolitan Adelaide that could see 1,000 new homes built.

The news was not as positive in other jurisdictions. For example, Queensland’s government boosted its First Home Owner Grant despite the evidence that it “works against improving affordability”.

In Victoria, this year the government has hiked land taxes, banned gas connections (raising construction costs), and from 1 May will require all homes be built to a seven-star energy efficiency standard, adding up to $40,000 to the cost of a standard new home. Those might be important considerations with benefits exceeding costs, but one indisputable trade-off is that they will make housing less affordable.

Moving to demand, there’s good news there too, from a pure housing affordability perspective. As expected, the rate of growth in student numbers looks to be slowing down:

“According to government sources, who asked to remain anonymous as they were not authorised to speak publicly, weekly approval rates throughout January were 30 to 40 per cent down on last year.

…

Home Affairs data [also] shows student visas are being refused at record levels. Nearly one in five applications for primary and secondary visa holders were knocked back in the six months to December 31.”

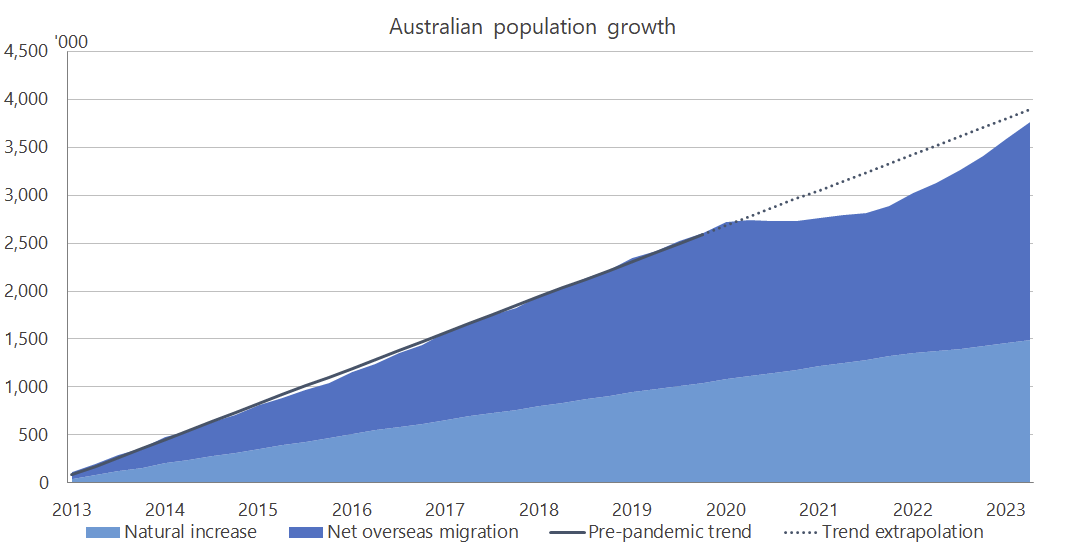

As at June 2023, the last available data point – Australia’s statisticians aren’t great at producing timely data – our population still hadn’t reached its pre-pandemic trend rate of growth. Given the catch-up was largely fuelled by the temporary phenomenon of backpackers and students arriving with no departures to offset them for a couple of years, we’re probably at, or very close, to that trend by now.

The rates of growth are temporarily high because of the pandemic border closures, but in level terms we’re still below the pre-pandemic trend.

The rates of growth are temporarily high because of the pandemic border closures, but in level terms we’re still below the pre-pandemic trend.

2024 is shaping up to be a good year for housing affordability! But fixing the housing market in this country isn’t a one-and-done policy decision; there’s still a lot more work to be done.

Maintaining momentum is critical

To understand how to successfully reform the housing market in Australia, sometimes it can be useful to look at previous structural reform initiatives. Personally, I find New Zealand’s 1980s-era “recipe” for structural reform with electoral success to be a good one – after all, structural reform can only be successful if it’s politically sustainable. The following points are taken from Roger Douglas’ The Politics of Successful Structural Reform, which is still insightful today:

- Implement reform by quantum leaps. Moving step by step lets vested interests mobilise; big packages can neutralise them.

- Speed is essential. It is impossible to move too fast. Delay will drag you down before you can achieve your success.

- Once you start the momentum rolling, never let it stop. Set your own goals and deadlines. Within that framework, consult widely in the community to improve detailed implementation.

- Credibility is crucial, is hard to win, and can be lost overnight. Winning it depends on consistency and openness.

- The dog must see the rabbit. Adjustment is impossible if people don’t know where you are going; you have to light their path.

- Stop selling the public short. Voters need and want politicians with the vision and guts to create a better future.

Breaking down decades of anti-development attitudes and regulations doesn’t happen overnight. The best course of action is to go big and fast, and while some states may intend to head down that path, they can’t get complacent: if house prices start to ease off due to a slowdown in population growth, a recession, or because the supply-side reforms themselves start working, politicians will be tempted to kowtow to vested interests and postpone any further reform efforts. In Roger Douglas’ words, that’s the default state of politics:

“Politicians tend to close their minds as long as they can to the need for structural reform, because they believe that decisive action must inevitably bring political calamity upon the government. As their country’s economy drifts closer to crisis and structural problems are no longer deniable, they persuade themselves that action within a relatively short time of an election would give the advantage to their political opponents. They convince themselves that this stance is justified by pretending that the opponents are deceitful and interested only in their own gain, not the country’s well-being. When the economic situation is serious enough to arouse public concern, both parties may, in many cases, seek to evade the issue by offering electoral bribes to distract voters from the real problems.”

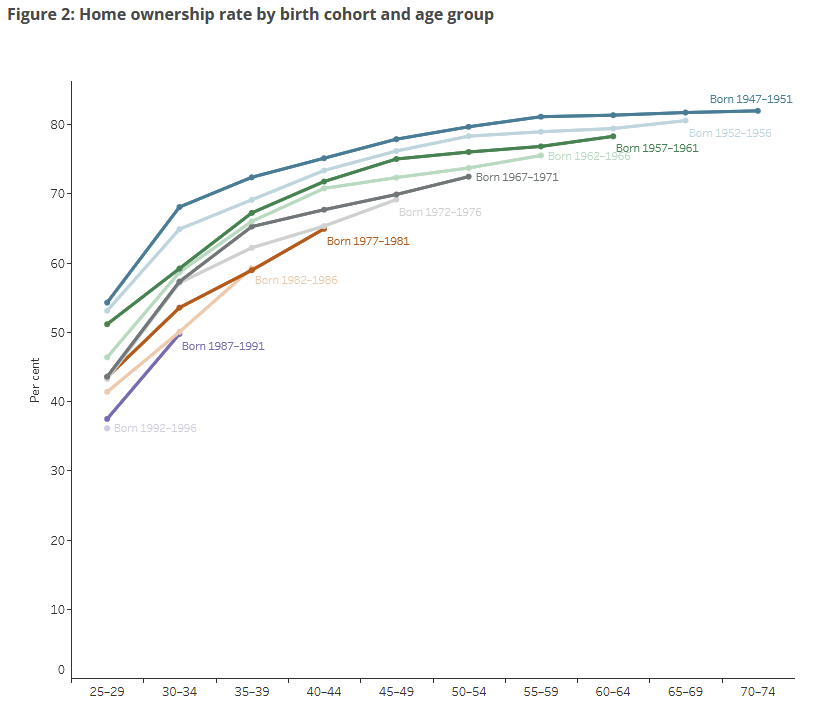

Former Prime Minister John Howard, justifying why he wasn’t concerned about housing affordability, once remarked that no one had ever stopped him in the street and said “you’re outrageous, under your government the value of my house has increased”.

He’s right, and that mentality needs to change if housing is to ever be affordable in this country. If it doesn’t, then there’s almost no chance of achieving long-term affordable housing, given the high rates of ownership among all age cohorts (homeowners are a big special interest group).

That’s a lot of voters who need to be convinced that rising property prices aren’t necessarily a good thing for the country.

That’s a lot of voters who need to be convinced that rising property prices aren’t necessarily a good thing for the country.

Douglas showed that it’s possible to reform and be politically popular, even if there’s some short-term pain for certain groups. But at all times you must ensure that the most vulnerable groups are protected, and communicate that the community as a whole will be made better off. Incidentally, that’s the strategy being used by Javier Milei in Argentina, who baffled attendees at the World Economic Forum who are very clearly of the default political mindset:

“People are intrigued because he managed to get elected on an austerity platform, by telling voters he would cut their benefits and state subsidies.”

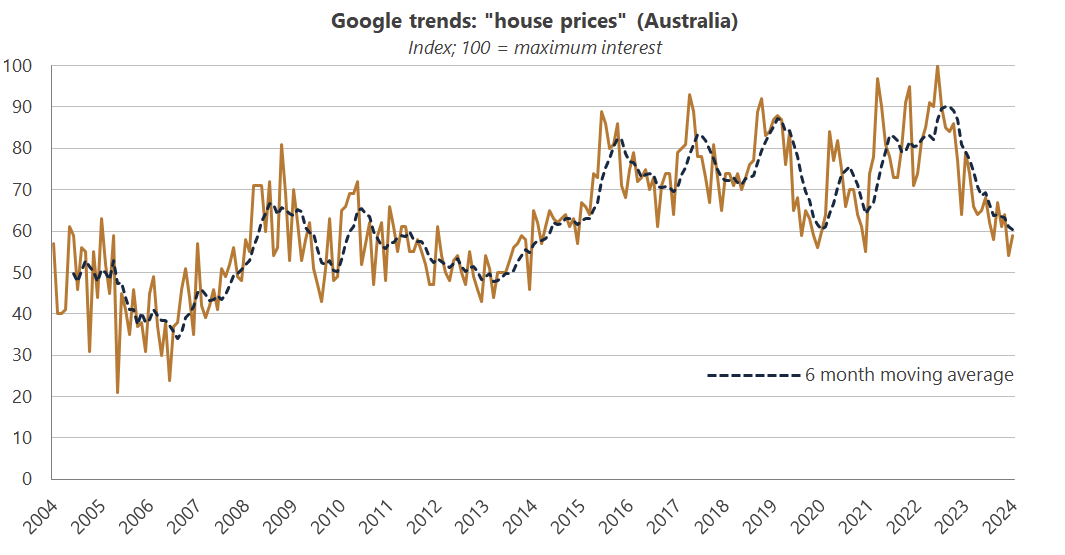

People care a lot about house prices in this country. Nationally, Google Trends interest has been trending up over the past two decades, with the most recent peak in interest coming in June 2022, which was around when the post-pandemic dwelling demand peaked (price growth was running above 20% annually). But it has been in free-fall ever since as rising interest rates have taken the frothiness out of the market.

The public’s interest in house prices as waned since peak growth in mid-2022.

The public’s interest in house prices as waned since peak growth in mid-2022.

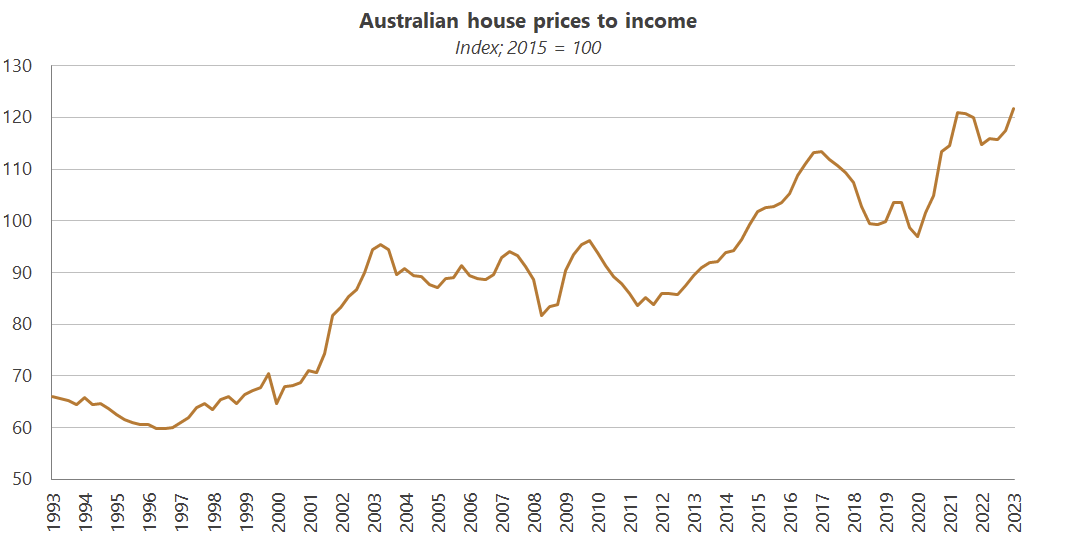

That suggests the public’s concern about house prices – at least compared to other issues, such as the cost of living – may be waning. That’s despite affordability continuing to decline: in Australia, it now costs about twice as much in terms of income to buy a house than it did in the mid-1990s.

As a share of income, house prices have never been more expensive.

As a share of income, house prices have never been more expensive.

The ratio of mortgage payments to income, which had been relatively stable at around 8% for more than a decade prior to the pandemic, have also reached record highs.

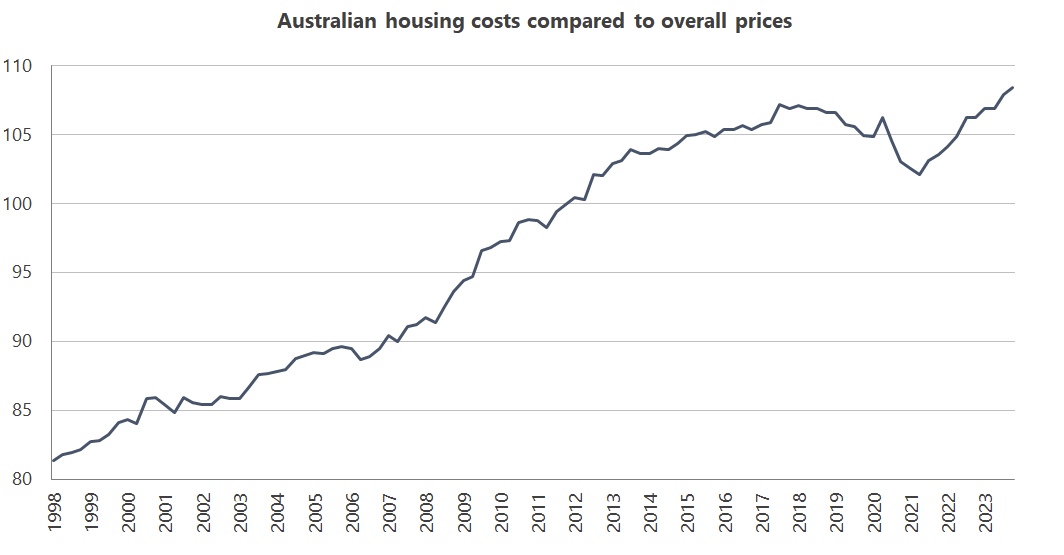

Another way to look at housing affordability is to compare it to the price of everything else people spend their incomes on. Housing costs have been rising faster than other goods and services since the late 1990s, and are now nearly 10% above overall CPI. In other words, houses are now also relatively unaffordable.

We’re almost back to the pre-pandemic trend.

We’re almost back to the pre-pandemic trend.

Our various levels of government look to be on the right track towards reversing this trend, although they could all still do much more.

Housing targets are the wrong approach

A central pillar of the the federal government’s proposed solution to the housing problem – announced just two months after the peak in housing interest (politicians bend with the wind) – is to create 1.2 million new homes in “well-located” areas, by providing $3.5 billion to state and territory governments that “achieve more than their Accord targets and undertake reforms to boost housing supply and improve housing affordability”.

Zoning laws are created and enforced by state and local governments, which is why this approach was taken. It’s just a shame that the government decided to use a target. Why, you ask? Because of Goodhart’s Law: now that housing completions are a target for state and territory governments, they will inevitably game them, and housing completions will cease to be a reliable measure of housing supply.

Housing takes time to build and the clock on the 1.2 million target doesn’t even begin until July 2024 , so completions data should be reliable until at least the end of this financial year. But over time, states and territories will do whatever they can to claim ’their share’ of the $3.5 billion carrot that the Albanese government has dangled in front of them. They will count “houses” that they shouldn’t, set up entire teams to work the system, or perhaps cut corners that leave people in homes containing serious defects.

When you throw money at a problem, it doesn’t always work out (you might recall the tragic “pink bats” scheme). According to lawyer Bronwyn Weir:

“The issue is that governments are spending millions and billions of dollars, including the federal government, to try to address housing supply.

…

The federal government should be demanding that states and territories are accountable for not just delivering new homes at a rapid pace, but new homes that meet the minimum standards of safety and compliance.”

The focus on completions is only getting more intense. Last month, NSW Premier Chris Minns – who admitted that his state " is last on the east coast when it comes to housing completions" – said that “it’s really important NSW is first on the east coast when it comes to completions”.

In this new competition, the priority for jurisdictions will be to:

- have more completions per resident than the other states, so as to bank as much of the $3.5 billion as possible;

- reach your targets, to save political face; and

- in a distant last place, consider whether what you’re doing will help housing affordability.

The game will only intensify going forward, with completions data telling us very little about trends in actual housing supply and affordability, which is what we should be caring about.

All housing is good housing

If the Albanese government had just created large incentives for increasing density-improving reforms, to be adjudicated by an independent body akin to the former National Competition Council, that would have been enough to get states, territories and local governments moving. Instead, in addition to the 1.2 million target, it decided to tack on a “well-located” clause, $2 billion for “social homes”, and $350 million for 10,000 “affordable homes”.

The 2022 Housing Accord defined “well-located” housing as “in and around train stations and TAFE campuses”. “Social homes” were not defined, while “affordable homes” were defined as “housing that is provided at below market rent to qualifying tenants (usually between 70 and 80 per cent of market rent)”.

Regular readers might know where I’m going with this: it’s far too prescriptive. The federal government doesn’t just want homes; it wants certain types of homes. By putting restrictions on the type of housing supply that qualifies, these conditions will make it more difficult for states to improve housing affordability.

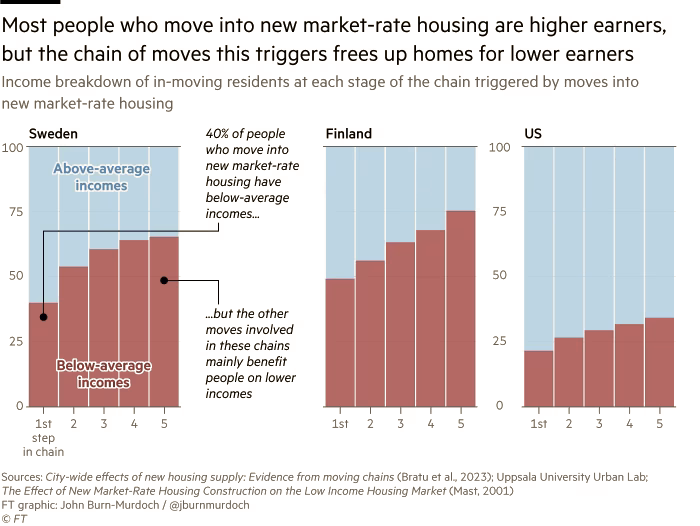

To borrow from the great Chinese reformer Deng Xiaoping, it doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white so long as it catches mice. The thing you have to understand about housing is that it all helps improves affordability, regardless of whether it’s “social” or “luxury”.

The domino effect of luxury housing helps everyone.

The domino effect of luxury housing helps everyone.

We need to build more houses, period. Given that we are surely approaching the physical and mental limits of urban sprawl in this country, most of the new housing is going to have to be medium and high density, which accounts for just 28% of our housing stock today. But rezoning suburbs away from single-family detached houses will not be popular with everyone and will need community buy-in (as Douglas would say, “the dog must see the rabbit”). Politicians have to communicate why higher density is important: many people can’t visualise the need for supply, and the natural tendency for residents is to object to density.

One problem with the current approach being adopted by many states is that they’re targeting specific areas for high density (often bypassing local government in the process), while leaving the vast majority of the adjacent land zoned for low density detached housing. That risks creating eye-sores and stirring up local angst, as developers push the boundaries on what is suddenly quite expensive land. A more sensible approach, as was successfully executed in Auckland, would be to up-zone all land to at least medium density. That would prevent the price of land rising as much, encourage development to spread out more evenly, and reduce the visual differences between existing and new housing.

Once again, communication is the key. Density gets a bad rap, but it doesn’t have to be a bunch of ugly, Soviet-style apartments. Just as low density doesn’t always have “character” (lots of parking lots, roads and the associated cars spring to mind), medium and high density housing can be done well, improving a suburb’s character and amenities.

Where’s the, ahem, “community character” in low-density developments like this?

Where’s the, ahem, “community character” in low-density developments like this?

Increased density can also help jurisdictions reach their environmental goals: with higher density we wouldn’t need as many cars, and investments in lower-carbon transport options like rail, bus, cycle and footpaths suddenly start to make economic sense. Fewer white elephants, fewer tax dollars wasted on infrastructure to nowhere.

Australians aren’t inherently opposed to density. For example, many of us love traveling to cities like Barcelona and Lisbon, which have estimated densities of 16,000/km2 and 5,446/km2, respectively.

Barcelona on the left, Lisbon on the right. Higher density doesn’t have to be ugly!

Barcelona on the left, Lisbon on the right. Higher density doesn’t have to be ugly!

By comparison, Melbourne leads the way in Australia at 503/km2, followed by Sydney 433/km2, Adelaide 426/km2, Perth 342/km2, and Brisbane 159/km2.

To solve our housing crisis, we don’t have to get anywhere near the kind of density some of Europe’s most vibrant cities have had for centuries. But we most definitely have to start inching ourselves in that direction!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!