Inflation's bumpy landing

Australia’s March quarter inflation figures were released last week and let’s just say if you were hoping for a rate cut anytime soon – perhaps even this year – you’re going to be left disappointed. Not only did the consumer price index grow faster than analysts expected at 3.6% annually, but it actually ticked up again to 1% on a quarterly basis, which if sustained would correspond to an annualised rate of around 4.1%.

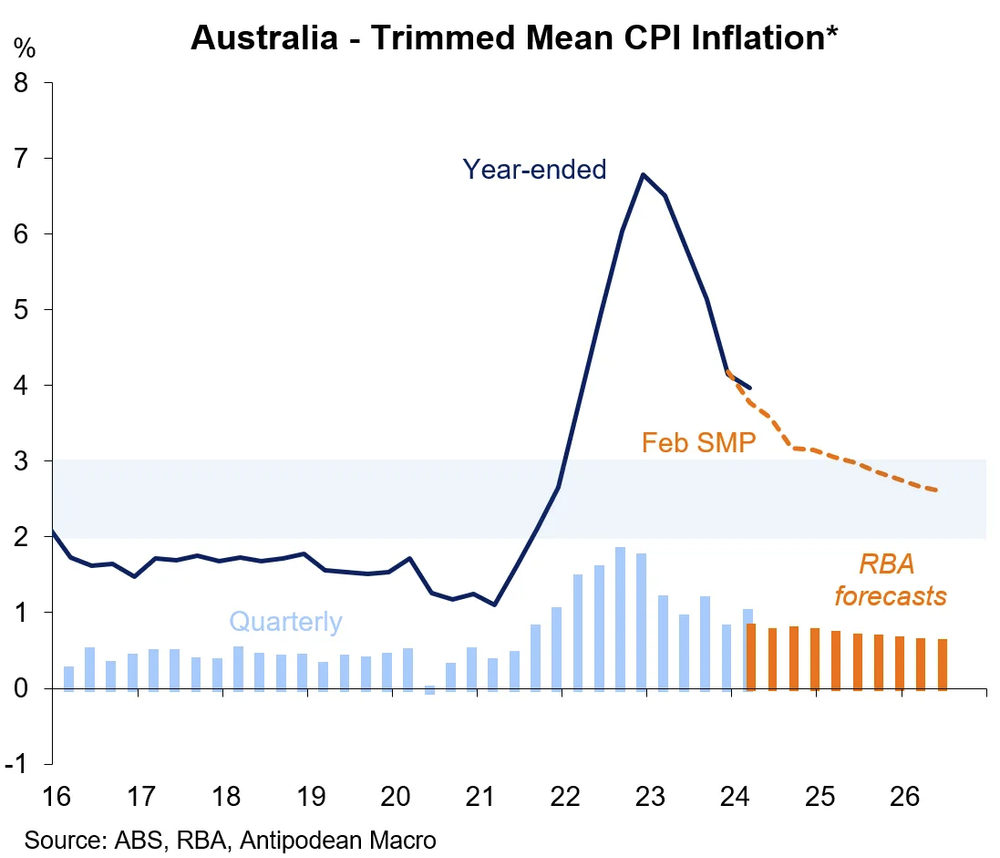

Perhaps more worryingly, the trimmed mean (core) reading, which strips out “volatile” items, rose 4.0% and is now above the most important forecast of them all: that of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

And don’t say you weren’t warned! I wrote back in January that:

“I think inflation might stay above the RBA’s 2-3% target for some time yet, which means we’re not likely to see rate cuts anytime soon – perhaps not even this year”.

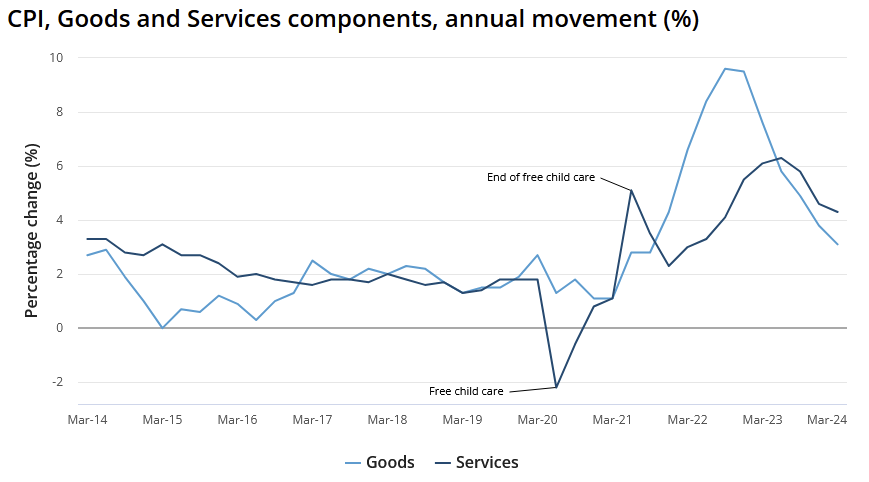

My reasoning was that “services inflation tends to be stickier than goods inflation”, and that’s exactly what’s happening. After hitting a high of 9.6% in September 2022, goods inflation is now growing at just 3.1% annually, while services inflation looks to be settling at an annual rate above 4%.

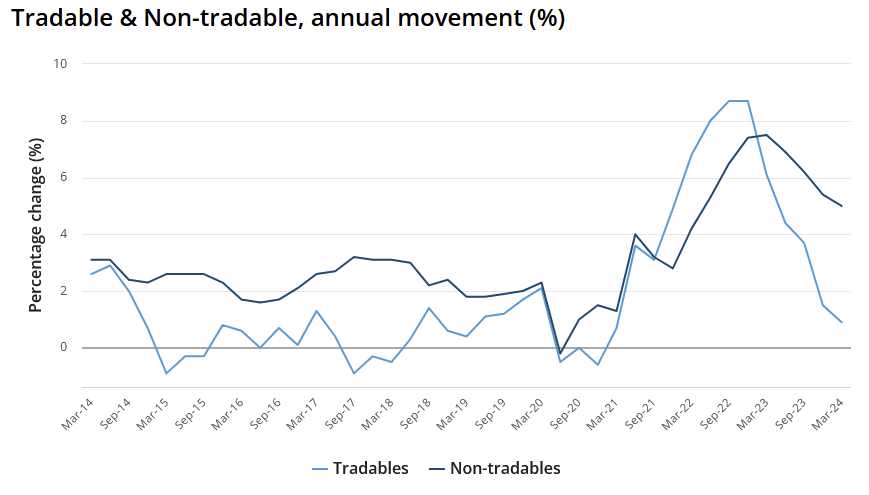

It’s a similar story with tradables versus non-tradables. While we can import disinflation from China and other countries that are investing too many resources in manufacturing – effectively subsidising foreign consumers – inflation in non-tradables is all about domestic fiscal and monetary policy goosing demand.

And on that front, we still have a lot of work to do, with the dichotomy between tradables and non-tradables especially noteworthy.

While tradables are experiencing disinflationary pressures, non-tradables look to be stabilising at an annual rate above 4%. If we can’t get services and non-tradables inflation back down, the RBA may not simply hold rates where they’re at for the rest of 2024 but could even raise them, with significant implications for the broader economy, particularly for households and businesses with variable-rate mortgages and loans.

Persistent and stubborn

Consultant Capital Economics recently wrote that “we now expect the RBA to hike rates by another 25bp (basis points) when it meets in two weeks’ time”.

That sentiment was echoed by Warren Hogan, a former Treasury economist, who argued that the RBA’s strategy doesn’t appear to be working:

“It’s [inflation] persistent and it’s stubborn. We’re trying to pull off something no country has ever done, we’ve never done. And that is get rid of inflation without a recession. Without a bad recession. And that’s that narrow path.”

And again in the AFR:

“Everything points to the fact that 4.35 per cent isn’t the right level for the cash rate. The RBA’s strategy this cycle doesn’t seem to be working. They were hoping we could do less than the rest of the world because we were more exposed to the nominal channel of monetary policy through variable rate mortgages … We just need to now get up to the [cash rate] level that other countries are, at 5 per cent.”

Hogan may well be correct but I’m still not sure the RBA will raise rates. While I don’t know whether new governor Michelle Bullock is an inflation ‘dove’ or ‘hawk’, her predecessor Philip Lowe was certainly on the dovish side of the spectrum. As deputy governor during his term and a lifer at the RBA, one might think that Bullock shares those views. But that’s pure speculation; we just don’t know enough given she has only been in the role for several month and she doesn’t speak publicly all that often.

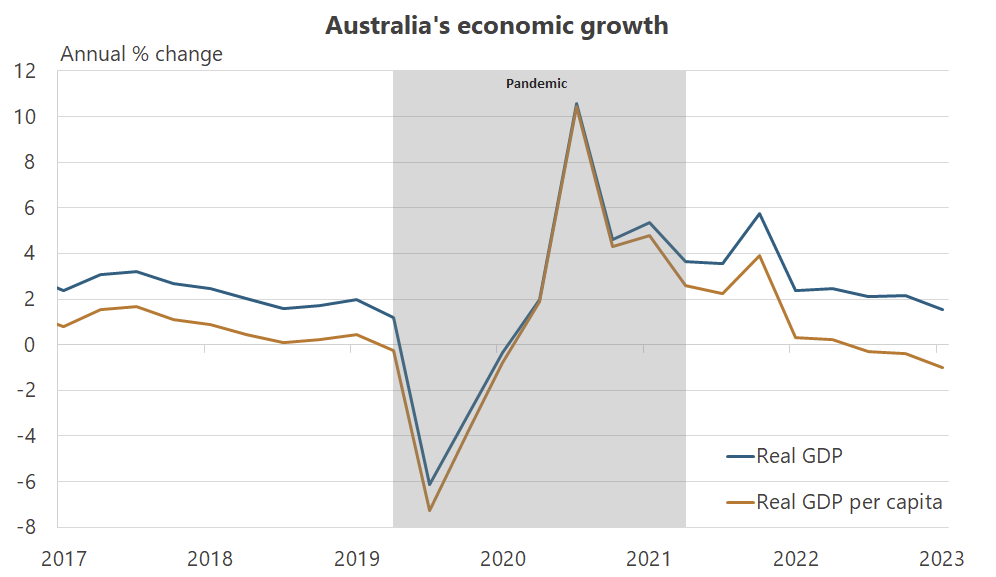

But regardless of what the RBA decides to do, at this stage, a recession looks all but certain. The economy has already contracted for three straight quarters on a per capita basis, with the only thing keeping us out of a technical recession being debt-financed fiscal spending and our high rates of catch-up migration following the pandemic’s border closures.

Just how much do migrants add to growth? A recent estimate from the US Congressional Budget Office predicted that “high rates of net immigration through 2026 will support economic growth, adding an average of about 0.2 percentage points to the annual growth rate of real GDP over the 2024–2034 period”.

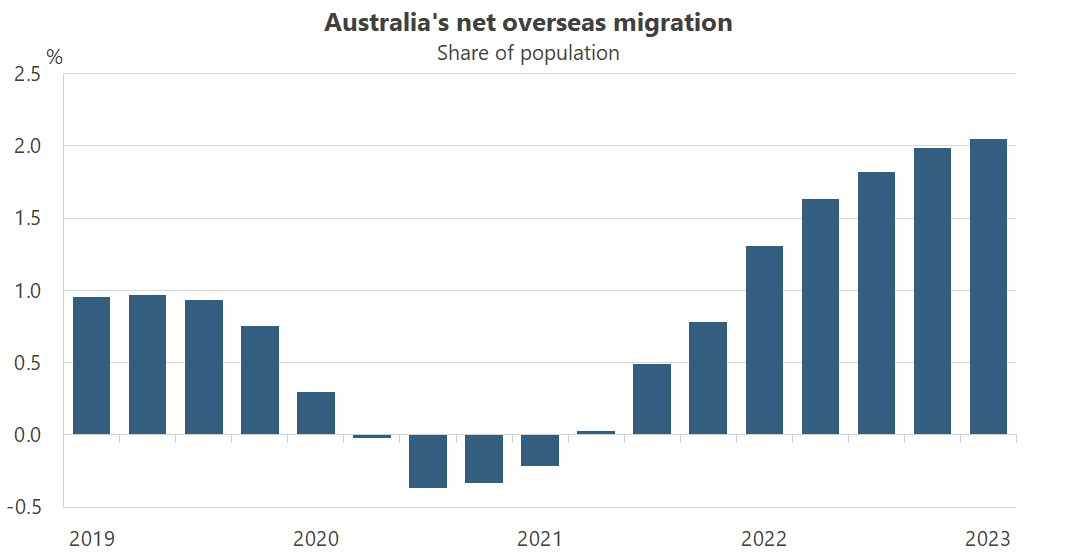

For context, in 2022 the “surge” in net overseas migration (NOM) in the US was equivalent to around 0.3% of their total population; in Australia, NOM has been running at closer to 2% of population in recent quarters.

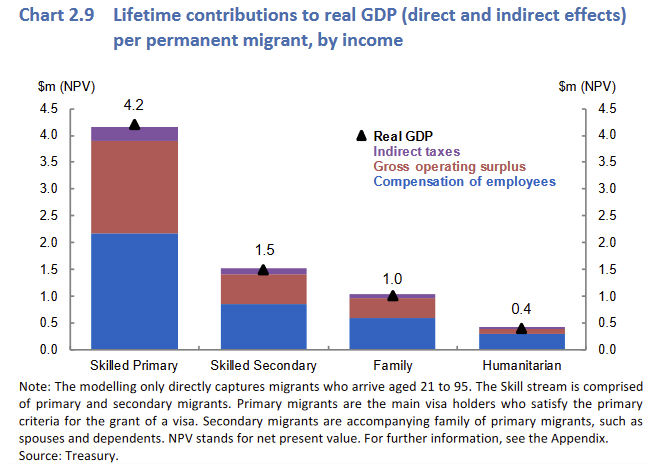

I don’t know what the migration multiplier is in Australia; I’m assuming it’s lower than in the US, because most of Australia’s migrants in the current wave are students who have strict conditions on the amount of work they can undertake. But regardless of the type of migrant, Treasury’s Intergenerational Report found that they all contribute to real GDP over their lifetimes.

In other words, given that quarterly real GDP growth was just 0.2% (0.8% annualised) in December, were it not for the recent surge in migration we’d probably already be in, or be very close to being in, a recession.

Monetary conditions aren’t all that tight

If the RBA has to keep rates higher for longer, or raise them, then economic activity is likely to slow even further. But while a recession – especially a deep one – would likely ease inflationary pressures, barring significant demand destruction such as that caused by a financial crisis (which no one should ever want to see!), inflation won’t come down immediately.

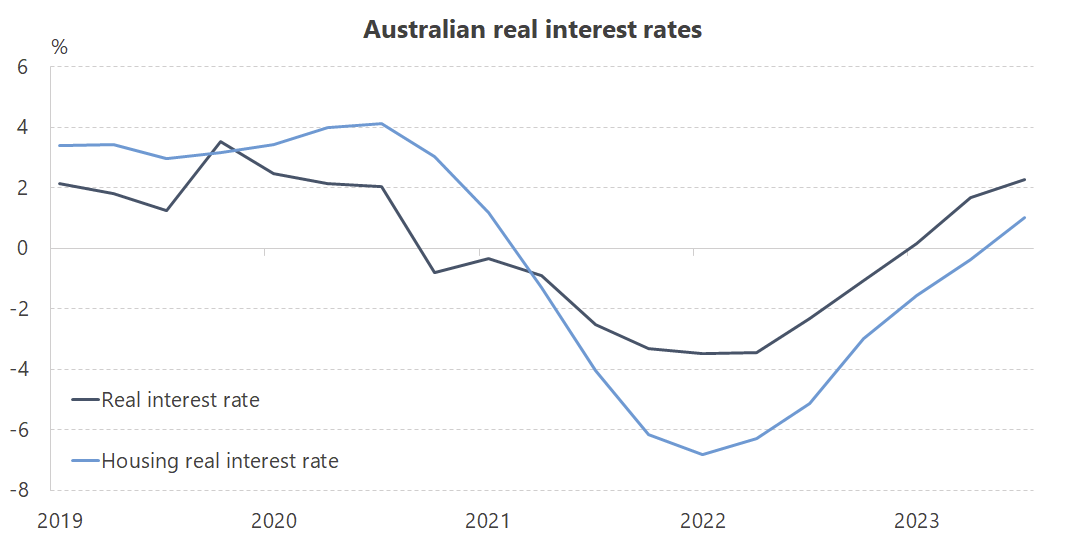

One reason for that is because real interest rates have only been positive for a few quarters. Housing real interest rates have only just ticked into positive territory – if you want to know why prices went so berserk, it’s because the banks, aided by the RBA’s rate cuts and term funding facility, were literally paying people to borrow money. Combine that with supply constraints and, well, Bob’s your uncle.

Real interest rates are owner-occupied housing lending rates minus the annual rate of growth in overall and housing consumer price indices.

Real interest rates are owner-occupied housing lending rates minus the annual rate of growth in overall and housing consumer price indices.

Interest rates are now positive and economic conditions are easing, but lags in the wage setting process mean that inflationary expectations may be embedded into nominal wages growth, raising the cost of services (for which labour is a major expense).

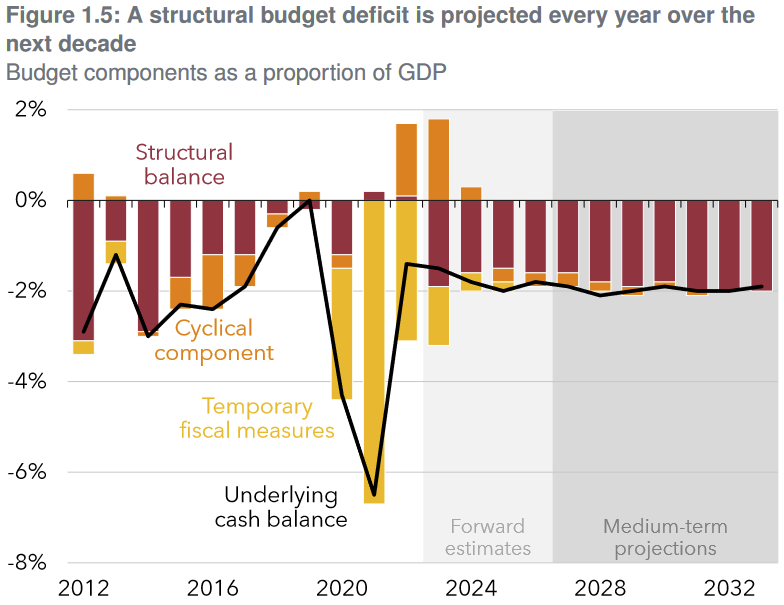

Another reason inflation is proving to be sticky is because fiscal policy remains stimulatory with structural deficits as far as the eye can see.

Additionally, lots of the economic reform led by this government – which is key to boosting the capacity of the economy, reducing labour costs and inflation – may have unintended consequences that exacerbate inflationary pressures (I speak, of course, of its foray into industrial relations and policy), ultimately undermining the RBA’s efforts.

We need more than just monetary policy

To get inflation down and avoid making the job a whole lot harder than it needs to be, fiscal and monetary policy need to work together rather than against each other:

“When they [the RBA] raise interest rates, that raises interest costs on the debt, someone’s got to pay for that and so fiscal policy has to tighten with monetary policy. And a lot of the experiences we’ve seen have been times that combined fiscal policy, monetary policy and economic reform. That’s what really helps inflation. It’s not obvious the monetary policy can do it all alone.”

We have a Budget coming up in the next six weeks, and while it will almost certainly report a surplus, it will be an operational surplus only. Net debt will continue to increase due to the government’s “investments”, which are stimulatory and will make the RBA’s job more difficult.

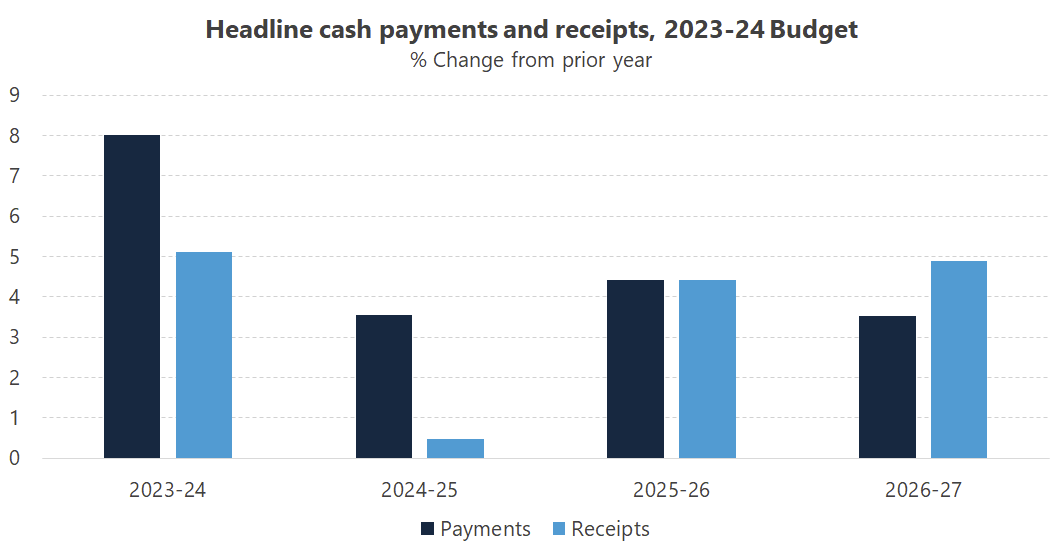

Worryingly, federal spending looks set to grow much faster than real GDP and revenue until at least 2026-27, noting it will be politically difficult to actually achieve those future reductions in spending growth given how much social spending – e.g. NDIS, aged care, health and defence – is effectively locked-in across the forward estimates.

As economic growth slows, unemployment rises from 50-year lows, and commodity prices moderate, revenue growth will slow or perhaps even contract. That means more deficit spending, additional interest payments, and higher inflation than we would have had if fiscal policy was working with monetary policy, rather than against it:

“What matters is structural surpluses over the 10 to 20 years that it takes to repay debt. Inflation fundamentally comes from more government debt than people think the government will be able to repay, but to repay over the long, long, long run.”

There are three ways to achieve long-run structural surpluses (and no, the faux operational surplus that the government will boast about in six weeks does not count): cut spending, raise taxes, or improve productivity and ‘grow’ out of it.

Meaningfully raising taxes from here would be rather difficult, given Australia already had the largest average tax rate increase in the developed world last year due to bracket creep and the government just spent it all, so changes to spending and structural reform look like the best options. Ideally you’d do some of all three, mitigating the costs of any tax hikes by undertaking badly needed, productivity-boosting tax reform, which would mean you don’t actually have to cut spending (just slow the rate of growth).

Even better, you codify “fiscal rules and institutional reforms that support disciplined fiscal policy”, so that it’s not always working against monetary policy; but good luck finding a politician willing to handcuff their ability to spend (and convince their colleagues to go along with it)!

Alas, the Australian public don’t appear to believe the government has a credible plan to achieve any of those policy options, with consumer inflation expectations 12 months from now rising to 4.6% this month. That’s well above the RBA’s 2-3% target and will be a mindset that’s tough to break, likely feeding into wage negotiations and services inflation for some time yet. Unless something suddenly changes, I just can’t see the RBA cutting rates this year.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!