iPhones and AI: What's next?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is still all the rage. Last week Apple finally joined the party, announcing that iPhone users would soon have access to ChatGPT through its Siri digital assistant, and that it plans to roll out a bunch of new AI features later this year.

It’s going to be interesting to see how Apple deals with the inevitable privacy and security issues that flow from this link-up with OpenAI. Elon Musk, who has long-standing beef with OpenAI and is building a competitor, went as far as banning iPhones from his companies:

“If Apple integrates OpenAI at the OS level, then Apple devices will be banned at my companies. That is an unacceptable security violation.

And visitors will have to check their Apple devices at the door, where they will be stored in a Faraday cage.”

Apple assures us that “requests are not stored by OpenAI, and users’ IP addresses are obscured”, but given OpenAI’s track record on respecting rules and intellectual property, a healthy amount of scepticism is certainly warranted.

But beyond consumer beware, it raises questions about how this industry should be regulated. The Australian government has made moves in this space, recently signing the Seoul Declaration and joining the Hiroshima AI Process Friends Group that will work towards “safe and responsible AI”. It has also worked with Singapore’s government to “test both country’s AI ethics principles”, and of course has its own interim response to “safe and responsible AI”, with a temporary expert group working until the end of this month to “advise us on testing, transparency, and accountability measures for AI in legitimate, but high-risk settings to ensure our AI systems are safe”.

The interim report probably gives the best indication as to the approach it will take, but a lot was left unanswered. With the ’expert group’ wrapping up at the end of this month, I’m sure a more concrete proposal to regulating AI will be forthcoming. Until then, here’s what I think.

What AI can, can’t, and may never do

Before regulating something, it’s important to know more about what it is, exactly, we’re regulating. And I think we need to be careful listening too closely to people in the industry about what AI can do (including its potential), as doing so might lead regulators astray. Those in the AI industry tend to be excellent salespeople, full of hype about their own products and they truly believe they’re on the path to making humans obsolete within years. Their sales pitches can be so convincing that on a recent visit to Silicon Valley, they managed to get a relatively well-known Chicago-trained monetary economist, Scott Sumner, to write that all communism needed to work was for everyone to as smart as the people working on AI:

“I’m probably giving you the idea that the Bay Area tech people are a bunch of weirdos. Nothing could be further from the truth. In general, I found them to be smarter, more rational, and even nicer than the average human being. If everyone in the world were like these people, even communism might have worked.”

Yeah, nah. What Sumner observed is collective delusion, reinforced by the fact these people are largely sheltered from the rest of the world while inside their Silicon Valley bubble. Large language models (LLMs) aren’t even on the road to artificial general intelligence (AGI); it’s actually astonishing how easily a group of very smart people can so easily veer wildly off course in their thinking – a warning to all technocracy fans out there!

But intellect is no excuse for ignorance; I would suggest they all go and read Hayek’s seminal paper The Use of Knowledge in Society, which cautioned against such hubris:

“Today it is almost heresy to suggest that scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge. But a little reflection will show that there is beyond question a body of very important but unorganised knowledge which cannot possibly be called scientific in the sense of knowledge of general rules: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place.”

A recent essay by independent technology analyst Ben Evans got me thinking about Hayek’s knowledge problem and AI even more. Evans asked ChatGPT how to apply for a visa to India, which the LLM got very wrong. And because of how they work, it’s hard to see LLMs ever getting questions like that right:

“This is an ‘unfair’ test. It’s a good example of a ‘bad’ way to use an LLM. These are not databases. They do not produce precise factual answers to questions, and they are probabilistic systems, not deterministic. LLMs today cannot give me a completely and precisely accurate answer to this question. The answer might be right, but you can’t guarantee that.”

An LLM can make a prediction about something using historical data – patterns – but it’s not, and never will, be capable of understanding the decentralised body of ever-changing, subjective, contextual and tacit knowledge in real time; knowledge possessed by people who cannot communicate it to third parties.

But while the billions of dollars that are being investing in LLMs will never lead to AGI, that doesn’t mean it’s all a waste. As Evans rightly notes, that would be “a misunderstanding”:

“Rather, a useful way to think about generative AI models [LLMs] is that they are extremely good at telling you what a good answer to a question like that would probably look like. There are some use-cases where ’looks like a good answer’ is exactly what you want, and there are some where ‘roughly right’ is ‘precisely wrong’.”

Those in the AI space hope that LLMs will, with enough juice, be able to become true general-purpose tools. If that goal is achieved, they will accomplish something even computers and smartphones, while technically general-purpose, failed to do: move beyond being shells for various “single-purpose software: most people don’t use Excel as a word processor”.

But we’re not even close to getting there, and such lofty heights may even be impossible for LLMs to ever reach. So it’s important for whatever regulatory regime our governments devise to be flexible enough to account for all possible outcomes.

The right way to regulate AI

The true AI believers, such as the brilliant but apparently naive Leopold Aschenbrenner, want AI development locked up behind government security classifications because of the perceived risks. A Silicon Valley insider, Aschenbrenner is incredibly optimistic about the technology:

“AI progress won’t stop at human-level. Hundreds of millions of AGIs could automate AI research, compressing a decade of algorithmic progress (5+ OOMs [orders of magnitude]) into ≤1 year. We would rapidly go from human-level to vastly superhuman AI systems. The power—and the peril—of superintelligence would be dramatic.

…

I make the following claim: it is strikingly plausible that by 2027, models will be able to do the work of an AI researcher/engineer. That doesn’t require believing in sci-fi; it just requires believing in straight lines on a graph.”

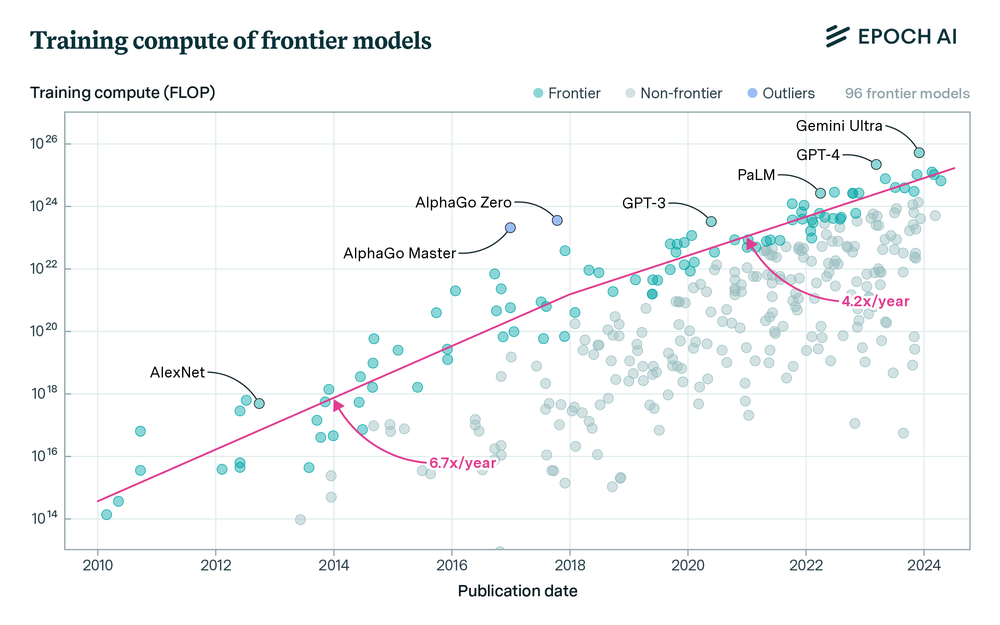

For those claims to be true it actually requires believing that LLMs are on the path to AGI (they’re probably not), and that the technology will keep growing exponentially with the same exponent. The latter is certainly plausible but assumes that we haven’t already reached something close to the saturation of training data, that the costs of training and running LLMs won’t also grow exponentially, and that the ~40% decline in the frontier model exponent we’ve seen in the last decade won’t happen in the next decade, too.

If those assumptions don’t hold indefinitely, then we could just as easily end up with something more closely resembling linear growth. Still a straight line, sure. But it would push Aschenbrenner 2027 claim out so far as to not be worth worrying about.

Joshua Gans, an Australian economist focused on competition policy and intellectual property research at the University of Toronto, recently offered a much more sensible approach to regulation than those proposed by so-called ‘doomers’ that tend to dominate the Silicon Valley AI thought bubble. According to Gans, there are three principal concerns people have with AI:

- Historical experience: New technology doesn’t necessarily produce net benefits.

- Identifiable harms: “AI has been used to surveil citizens, to imitate individuals through deepfakes, and to enhance military weapons.”

- Unintended and unforeseeable consequences: “For example, there is now widespread concern that social media is damaging children’s mental health.”

These are all legitimate points but I found it interesting that the final example, while popular among those who trust the media, rests on dubious grounds – although perhaps that actually reinforces Gans’ point that whatever we decide to do with AI, we shouldn’t rush into it:

“The fact that unintended consequences are often difficult to reverse poses its own problems, and appears to force a binary choice between AI or no AI. But this is a false dilemma. In fact, it means that we should engage in more small-scale experiments with AI to identify potential harms when it is still possible to limit their damage.

…

The potential irreversibility of a new technology’s unintended consequences also suggests a more nuanced and multifaceted role for AI regulation. We must engage in continual research to identify consequences immediately after they appear and to conduct appropriate cost-benefit analyses.”

For me there are two main risks for AI, neither of which involve some super intelligent AI turning us all into paper-clips. The first risk is that bad people will use LLMs as part of their arsenal against the rest of us. While I’m not sure we need specific AI regulation to deal with that above and beyond our current laws, we can’t rule it out and some modernisation might be beneficial. So as Gans suggests, appropriate cost-benefit analyses should be done on whether it’s in our interests to write some AI-specific rules into what we already have.

The second risk is that, filled with fears of becoming paper-clips, we go too far and end up neutering what’s a promising technology and the many benefits it might bring.

Beware the moat

An internal Google document that leaked around a year ago admitted that “We have no moat and neither does OpenAI”. The document was, of course, referring to the fact that in the arms race of AI, there are no entry barriers to slow down potential competitors. But that hasn’t stopped them from trying to build one: in his recent testimony to Congress last year, OpenAI’s founder and CEO Sam Altman called for “a new agency that licenses any effort above a certain threshold of capabilities”:

“I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong. We want to work with the government to prevent that from happening.”

OpenAI now has 35 in-house lobbyists, and that will increase to 50 by the end of 2024. If you’re a dominant firm in a contestable market worried about competition, regulation is often music to your ears. Those open source models popping up at a cost of $100? Gone; they simply won’t be able to meet whatever licensing or testing requirements the new agency – which will inevitably take advice from people like Aschenbrenner and Altman, especially as governments won’t be able to pay the million-dollar salaries needed to attract top AI talent – imposes on them. Entry is then restricted to large companies which can afford the added costs.

It’s a tried-and-true strategy used by monopolists from Alcoa to Standard Oil and is well documented in the literature. There’s a reason the disgraced former CEO of FTX, Sam Bankman-Fried, was quite keen on crypto regulation – who knows how long he might have been able to keep the ruse going without competition!

Remember this guy? He was a big fan of his industry being regulated. Source

Remember this guy? He was a big fan of his industry being regulated. Source

Could AI go wrong and cause more harms than benefits? Absolutely, which is exactly why governments should be conducting “appropriate cost-benefit analyses”. Public safety – like national security – is one of the more common arguments for regulation (protection), whether legitimate or not. We should take the views of AI doomers, especially when they stand to personally benefit from any measures that slow progress and increase the size of their proverbial moat, with the appropriate amount of caution.

As it stands, AI such as ChatGPT are not really intelligent at all; they’re nothing but very large, predictive language models and there are signs that they’re already hitting a wall of diminishing returns (the low hanging fruit used to train them has been picked). Add to that the fact that robots are still pretty awful and require many humans just to maintain them, even if an evil, self-improving AI wanted to wipe out humanity, “it will be a gradual, multi-decade process”.

We already have a litany of laws and regulations that are well equipped to handle many possible unintended consequences of AI. And given where AI is at after years of work – even in lowest of low hanging fruits, customer support, LLMs " can only be trusted to take the simplest of actions" – the best course of action might just be to let this new industry play out and deal with any consequences as and when they arise.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!