Is Albo a YIMBY?

After winning a second term in government last month, Anthony Albanese delivered the following statement:

“I say this message to the Senate and members of the House of Representatives: we have a clear mandate to build more housing. The key is supply. Get out of the way and let the private sector build it. That is going to be one of my priorities.”

Notwithstanding his improper use of the word mandate, the rest of what he said was spot on. For too long our governments have restricted supply only to respond by stimulating demand, the end result of which has been huge waste and higher prices.

In fact, Albo is guilty of doing exactly that himself, contributing the ‘dumb’ half of the federal Labor–Liberal ‘dumb and dumber’ housing policy duo. The cycle has repeated itself so often that even bankers, who generally do well out of demand-side housing stimulus, are now speaking out against it. Here was NAB’s Andrew Irvine touching on the subject as he released his bank’s latest financial results:

“If all we do is stimulate demand-side factors and don’t get more dwellings under construction, you’re not going to get more Australians into homes because there are no more homes for them to move into.”

But could that all be about to change—might Australia finally break free from the politician’s syllogism, at least for housing?

In the US, a new “abundance” movement inspired by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson has been quietly infecting the centre-left Democratic party as Donald Trump leads the Republicans in the opposite direction—toward economic populism and anti-growth nationalism. It’s too early to know for sure if that newly-formed faction will win out at the next election, or if the Democrats will once again succumb to the Elizabeth Warren acolytes who dominated the Biden administration.

But it has certainly been influential, even in Australia.

Albo’s comments, plus a recent speech by Andrew Leigh (the new Assistant Minister for Productivity), offer a glimmer of hope that the abundance agenda might have found its way into Australia’s federal Labor party. Leigh even tweeted a photo of himself with the YIMBY (yes in my backyard) Melbourne group, holding up their business card:

Here’s the part of Leigh’s speech where he directly addressed what the abundance agenda is trying to tackle in the context of housing:

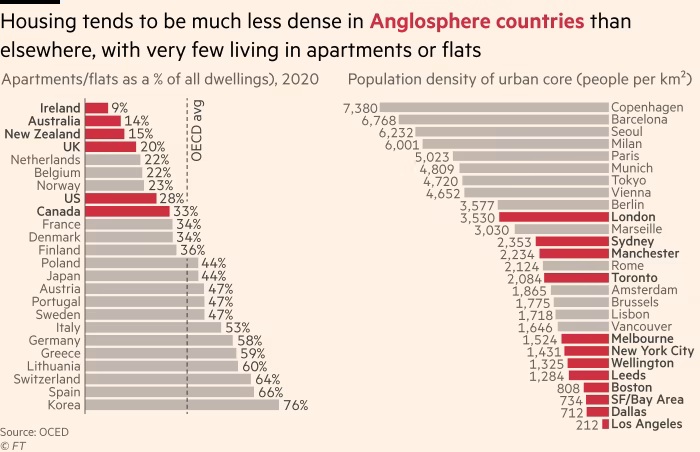

“In almost every major Australian city, the story is the same: too few homes, delivered too slowly, at too high a cost. And while interest rates and construction prices play a role, the underlying issue is institutional. We’ve designed a housing system where it is simply too hard to build.

…

The result is that new supply lags well behind need. The drivers of demand aren’t just demographic – they’re structural. We have more single‑person households. More people living alone later in life. More renters in long‑term tenancies. As household formation changes, the housing system hasn’t adapted. In some parts of Australia, building a townhouse requires the patience of a monk and the paperwork of a tax audit.”

It’s just really hard to build anything in Australia these days because there are so many people with an effective veto power at every step of the way. Leigh continued:

“Too often, the planning process is built for avoidance, not delivery. Zoning schemes reward conformity over quality. Local objections – however sincere – can block projects that meet broader strategic goals. Infill development is frequently stymied by rules designed to protect ’neighbourhood character,’ even in areas within walking distance of jobs, schools and transport.”

Yes. As just one example, almost everyone agrees that we should have more density near our inner cities and close to public transport nodes like heavy rail (Leigh quoted a figure of 94% in favour). Yet when the NSW government tried to enable just that by rezoning land within 400 metres of four railway stations to allow buildings up to six storeys, the Ku-ring-gai council unanimously agreed to sue them.

That’s the sort of obstructionism that has to end if Australia is to ever have housing abundance. And as good as Leigh’s speech was at pointing out problems, it was lacking in decisive action. From what I could gather, this was the extent of the policy agenda:

“We need states and territories to work with the federal government to deliver a system that recognises the pace required – not by skipping safeguards, but by sequencing them better. A system that integrates planning with delivery, consultation with construction, ambition with execution.”

Of course I agree with that statement, but I’m not convinced that the Albanese government will change its spots and actually… do it. Indeed, despite having set up a Housing Accord with an ambitious target for new housing supply, the Albanese government has so far failed to deliver.

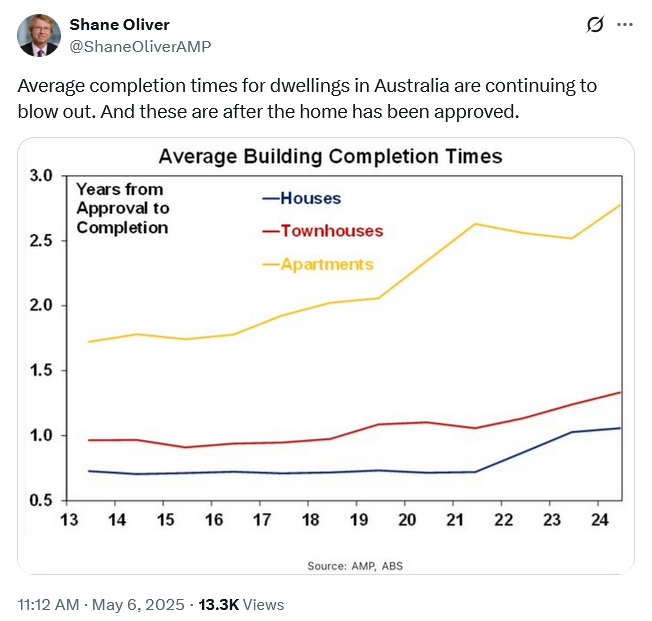

Perhaps unsurprisingly, recent Australian housing data aren’t anything to write home about; average completion times have continued to grow for all forms of housing, likely due to Australia’s deteriorating construction productivity:

That’s in part because the Accord itself was flawed. As I wrote last year:

“[T]o fix the housing crisis, a federal government has to work with the states. Labor’s Housing Accord – at least when it was initially announced – appeared prepared to do that, with states committing to ’expedite zoning, planning and land release for social and affordable housing’, and to ‘working with local governments to deliver planning reforms and free up landholdings’.

But that was 2022. I went through what the states planned to do to meet those stated goals, and it wasn’t promising: most states just included catchy phrases to tick the box, like ‘streamlining the planning approvals assessment process’ (VIC), or undertake ‘planning reforms that streamline planning approvals’ (QLD).

When something concrete was offered, such as in NSW where the government pledged to reduce minimum lot sizes and roll out ‘a consolidated package of planning reforms’ (and actually did it), the actions have been significantly watered down following the dreaded ‘consultation’ process and local push-back.

Most troubling – and this goes to the root of the problem with the Housing Accord and why it won’t do much to improve affordability – is that every measure has some kind of ‘social and affordable dwelling’ condition attached.”

On the latter point, Klein and Thompson explicitly warn against such “affordable housing” traps, which they say highlights “the grim absurdity of liberal [centre-left] housing policy”:

“Liberals lament that private developers want to build profitable developments when what is needed most is affordable housing. But even aside from how much housing is built, one way to make housing more affordable is to make it cheaper to build. The problem is many liberal jurisdictions have layered on rules and regulations that make housing pricier even when it is constructed—and that, of course, makes it less affordable.”

So what’s going on, and why is it so difficult to change anything when even the Prime Minister and one of his assistant ministers clearly understand that the housing crisis is a supply issue?

The problem, as usual, is politics. Upton Sinclair famously observed that “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

That’s also true for politicians, especially at the local level where organised NIMBY (not in my back yard) groups can and do swing elections against them. So while change needs to happen at the local level, the impetus for it probably needs to come from the top, where politicians are less susceptible to a local minority’s influence. Here’s Klein and Thompson again:

“The political economy of those ideas [building homes when housing is scarce] is fraught. It requires passing law after law in city after city. Today’s housing rules are exquisitely local, which would be appropriate if housing policy was bound by city limits. But the consequences of housing policy reverberate across states, and even across the nation. Gate the great cities of California and families flee to Texas and Arizona. When you allow housing to become scarce where the wages are highest, you shut down a powerful engine that long kept social mobility in America high. So what level of government—and of society—is appropriate for housing policy? Should it be run by states? By the federal government?”

But there’s yet another problem. In Australia, Sinclair’s quote could probably be rewritten to “It is difficult to get houses built when the nation’s wealth depends on not building them.”

The fact is most Australian households own their home (67%), and a majority of those owners (52%) have a mortgage. As Cameron Kusher recently wrote, housing and land are the preferred asset classes Australians use to save:

“As at Dec 24, residential land accounted for 37% of total household assets, superannuation was 20.5%, dwellings were 15.5%, currency and deposits were 9.1% and shares and other equity were 7.8%. More than one third of household assets sits in residential land which is up from 34.7% a decade ago, 34.3% 20 years ago and 26.7% 30 years ago.”

You’re just not going to win an election by promising to reduce people’s wealth, so deliberately reducing nominal house prices through more supply is a political non-starter. That means the best you can hope for is a reduction in real house prices, or at least a policy that prevents prices from rising even further as a share of incomes.

And achieving that would be a significant victory—for both housing affordability and Australia’s economic well-being: in a functional market, housing costs as a share of income should fall as incomes grow. Recent studies have estimated that the income elasticity of housing demand is below one (somewhere between 0.25-0.75), i.e., if incomes increase by 10%, the share of spending on housing should fall by 2.5-7.5%.

That this hasn’t been happening in Australia is evidence that housing supply is relatively inelastic and owners are capturing some of the nation’s real income gains. You don’t have to reduce nominal house prices to eliminate such ill-gotten gains (whether deliberate or not); you just have to let the market function properly again!

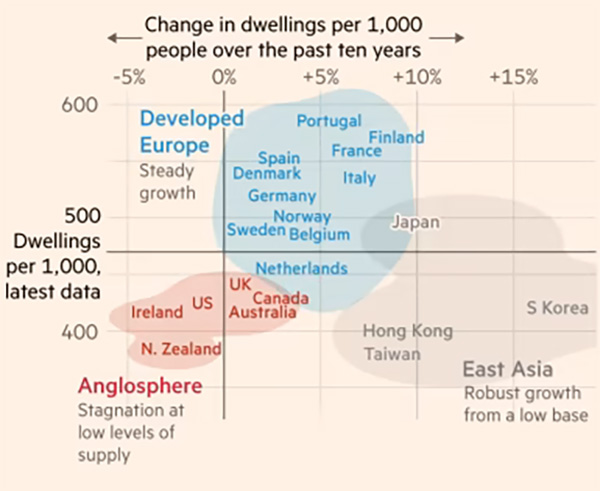

Indeed, nominal house prices are unlikely to fall anyway because we’ve under-built housing for so long that there’s enormous pent up demand. It could take a decade or more of cutting regulatory costs, improving construction productivity, and just building houses before nominal prices even begin to ease:

Anyway, I’m glad that we’ve now got politicians who are at least willing to discuss an abundance agenda for Australia! There’s certainly plenty that can be done to clear the way, if the Albanese government is as serious about getting stuff built as Albo and Leigh claim to be. It won’t be easy, but generational reform never is.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!