It's time for CANZUK

I’m sticking with the geopolitics theme today because with the ongoing situation in Ukraine and a flotilla of Chinese warships now off the coast of Western Australia, it seems as relevant as ever.

There was also more news out of the US. First, Senator Mike Lee and Elon Musk called for the US—a founding member of NATO, or the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation—to leave, because it’s a “raw deal for America”.

That’s despite the fact that the only time Article 5 has been invoked was after the September 11 attacks, which clearly benefited the US.

Second, Trump repeated his attack on Canada, insisting that:

“Canada should be our 51st state. No tariffs, no nothing. We give them military protection. They’re about last in NATO. They say, ‘why should they spend on military, the US protects us.’ That’s true. It’s not fair. They couldn’t exist if they had to pay their way.”

He has a point on military spending: Canada spends just 1.3% of GDP on its military, putting it above only Luxembourg, Belgium, Spain, Turkey, and Slovenia (for reference, Australia spends closer to 2%, the US is at around 3.5%, while China is officially at 1.7%, but that’s debatable).

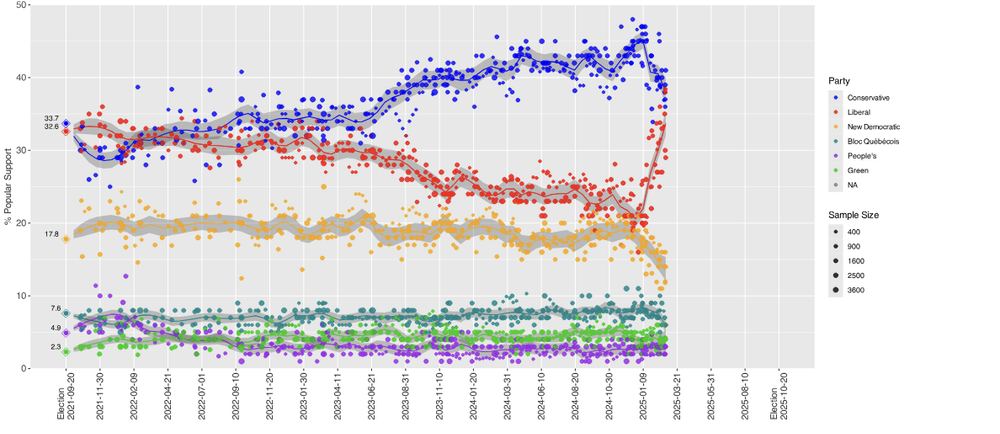

But to suggest that Canada’s lack of military spending means it should cede its sovereignty to Trump really gets to his zero-sum world-view, where international relations are all about extracting maximum benefit for the US now without regard for the longer term consequences. And one of those consequences may soon be realised—Canadian opinion of Trump is now so low that he has managed to swing their upcoming election from a Conservative landslide back in favour of Trudeau’s Liberals:

Mutual trust, long-term stability, or unintended consequences are second-order concerns for Trump. He treats foreign relationships as business deals rather than strategic partnerships, and he’s willing to bully weaker nations into compliance if need be.

So, what happens if Trump one day wakes up and decides that the alliance with Australia is a rotten deal for the US? While Australia has been off the Trump radar for now (our remoteness comes in handy sometimes!), an erratic, antagonistic and untrustworthy administration certainly raises questions about the future of the relationship.

America’s denouement?

On Monday, The Australian newspaper asked the following questions:

“Has Pax Americana reached its denouement – not at the hands of autocratic challengers but a wannabe American dictator named Donald Trump?

And will Trump’s love for authoritarian strong men embolden China’s Xi Jinping to flex his military muscles in the seas around Australia?”

If you have studied history, your answer to both questions is likely yes. The US has now passed what Niall Ferguson has dubbed “Ferguson’s Law”—not after himself but Adam Ferguson, who in 1767 observed that many a great nation had fallen into “national ruin” through the accumulation of an unsustainable debt burden:

“Ferguson’s Law states that great-power decline is the very likely consequence of excessive indebtedness. The critical threshold is not, as has sometimes been hypothesised, a particular level of the stock of debt relative to gross national product. It is when the percentage of output devoted to interest payments exceeds the percentage spent on military capability [the ‘Ferguson limit’].

…

America’s military commitments, unlike China’s, are global in extent, as has been true since 1945. Yet the US fiscal position is today far more constrained than at any time since then. The US government is now in violation of Ferguson’s Law and likely to move further beyond the Ferguson limit in the coming decades.”

There are two ways out: radical reforms of entitlement programs to fix the structural deficit, or a productivity miracle. But for every year the US stays above the Ferguson limit, the more difficult it will be to reverse the decline, and the more likely it is that “strategic rivals challenge its position”:

“One inference that might be drawn from the historical cases featured in this paper—particularly the 20th-century British case—is that a great power can afford to cross the Ferguson limit for a few years, provided it is capable of reducing its debt-service burden and increasing its military spending in the face of a growing external threat.”

An America that has succumbed to Ferguson’s Law has clear implications for Australia—for example, in the face of a regional conflict it might decide that of all its global military commitments, defending Australia is no longer a worthy goal.

It wouldn’t be the first time that happened, either: after the fall of Singapore in WWII, Churchill made it clear that “defending Australia from Japan was of little importance to Britain”, a decision that ultimately contributed to “moving Australia’s primary foreign policy allegiances from Britain to the United States”.

Given the US is fiscally stretched and a mercantilist Trump appears dead-set on moving back towards isolationism, Australia may soon need to pivot again.

Enter CANZUK

There’s no obvious replacement for Australia’s alliance with the US. The tyranny of distance is very real, and it’s both a blessing and a curse: we’re somewhat protected from threats by, to use Trump’s words, “a big, beautiful ocean”, but that ocean also separates us from would-be allies.

Still, that doesn’t mean Australia can’t increasingly look to broaden its trade and military ties with other like-minded nations, such as Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom – together known as “CANZUK”.

Senator James Paterson has been advancing the Australian side of things since Brexit, noting that all have shared values and common institutions: among the top 10 freest economies in the world; compatible common law legal systems; Westminster style-parliamentary democracies; and part of the Commonwealth.

The pandemic put a premature end to the last round of discussions, but if anything is going to give it a jump-start it’s a second term of Trump. And there’s a lot to like about it: other than their cultural and historic similarities, the four nations have a combined GDP of around nine trillion international dollars, which would make them the fourth largest economy in the world.

They would also have the third highest military spending, behind only the US and China. Throw in the fact that the UK is a nuclear power, Canada already has nuclear energy and might want weapons given its fraying relationship with the US, and Australia—depending on the outcome of the upcoming election—might soon be interested in both, and you have a powerful deterrent against would-be aggressors.

Doing the deal

What might a CANZUK deal look like? The short version is you would expand the Closer Economic Relations (CER) agreement that Australia and New Zealand already enjoy:

“This is an agreement that the World Trade Organisation has described as ’the world’s most comprehensive, effective and mutually compatible free trade agreement.’

…

[I]t is a perfect blueprint for what’s possible, and an appropriate medium-term goal for the Australia-UK relationship.”

Using the CER as the model, a future CANZUK agreement might include:

- Mutual recognition of goods, allowing products sold in one country to be legal in all others.

- Occupational recognition, allowing registered professionals in one country to practice in the other.

- Free trade in goods and services through the elimination of all tariffs and trade barriers.

- Free movement of labour, with citizens of all countries able to live and work in the other country without needing a visa.

- The ability to access each country’s government procurement processes, i.e. bid for contracts on equal terms.

Now, you wouldn’t have all of that from day one. It took Australia and New Zealand “30 years of gradual, deliberate and sustained fine tuning, evolution and development” to get to where they are today.

Canada might also be a major sticking point in any negotiations: it doesn’t even permit a lot of the items on the above list between its own provinces, let alone other countries, so it would need to get its own house in order first—although there’s nothing like having an increasingly unhinged neighbour to the south to motivate you!

But even without a fully committed Canada, there’s no reason why it couldn’t start as ANZUK, perhaps with Canada’s initial involvement being as a ‘future partner’ until it can credibly commit to the above terms.

The best thing about the CER model is it avoids a European Union-style loss of sovereignty, where decisions from immigration to the curvature of bananas are determined in Brussels, not London, leading to Brexit.

It achieves that in two main ways. First, politicians would maintain full control over who comes and goes, and the benefits for which they’re eligible: for example, New Zealanders only get limited access to Australia’s welfare system, while Australians going the other way get full access to New Zealand’s, reflecting the relative generosity of the two systems.

Second, there would be no trade harmonisation, where participating countries have to bicker amongst one another and agree on one standard for all, which in practice results in costly, zero-sum lobbying.

Mutual recognition, by contrast, achieves the same goal – making it “easier to do business across borders and give consumers a wider and more competitive range of goods and services” – while still allowing for regulatory independence through exemptions that “undermine individual jurisdictions’ sovereignty” (permanent) or threaten “health, safety or environmental” (temporary).

Now, that all sounds good to me—but the first question any well-meaning nationalist would ask is: wouldn’t there be huge migration flows from one country to another, causing all sorts of issues for their infrastructure, housing, and so on?

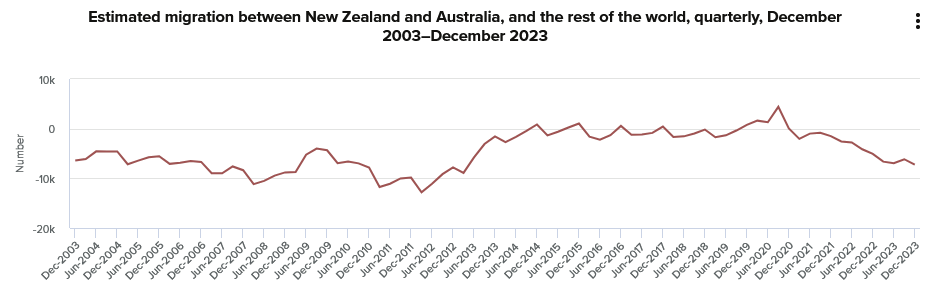

That’s certainly possible, and New Zealand regularly sees an exodus of workers to Australia due to higher salaries and better opportunities across the ditch.

But such flows are small—“about 30,000 a year during 2004–2013, and 3,000 a year during 2014–2019”. And given that Australia is the wealthiest of the four nations, and New Zealand the poorest, it’s unlikely that flows to/from Canada and the UK would be significant, especially given the greater distances involved.

The increased flow of people between countries also has large benefits, not only for the workers themselves (who are able to improve their living standards), but by better matching workers to employment where they’re most productive. And if net outflows truly become a problem, then the solution is for the affected country’s politicians to remove any roadblocks that stand in the way of their own economic success.

In that sense, the free movement of labour between the countries is, in the long-run, almost certainly a net benefit: if politicians undermine their country’s growth-enabling institutions too severely, competition from the other jurisdictions will act as something of a ‘check’ on poor policy-making—i.e., incentivise politicians to adopt policies that enhance growth to retain talent.

Still, at first it would inevitably be a prickly issue, and so rather than completely free movement, special visa categories with relatively relaxed conditions to go with free trade and mutual recognition would be a good start for any CANZUK agreement.

Pie in the sky stuff, to be sure. But crazier things have happened, and there’s nothing like a geopolitical crisis to open people’s minds to new ideas!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!