It's time for fiscal rules

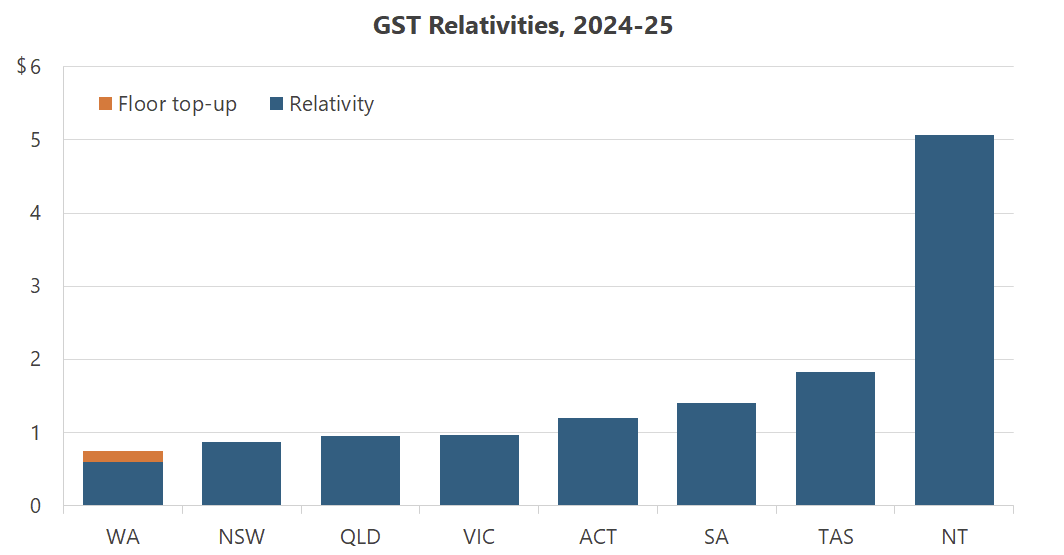

Oh boy. Another year, another GST carve-up that led to a flurry of complaints from the states that ’lost out’. This time it was the NSW and QLD Labor governments that were the most vocal, with NSW facing a $310 million cut, while QLD lost $469 million. For context, that’s a total revenue cut of around 0.25% and 0.55% in 2024-25 for each state, respectively – closer to a Budget rounding error than a major policy decision.

But you wouldn’t know that from the cries of anguish that bellowed from the Premiers of those states, Chris Minns and Steven Miles, which were no doubt heard all the way in Canberra. According to Minns:

“It’s just not reasonable for me to say to the NSW taxpayers (that we’re) either going into further debt, or we’re going to tax you more because Western Australia, and Victoria (have demanded) even more of their GST share.”

Other than NSW and QLD, no other state “demanded” more of their GST share this year. The distribution is determined by the independent Commonwealth Grants Commission, which weighs the revenue-raising capability and ’needs’ of each state under a rather complicated system of horizontal fiscal equalisation.

You can debate the pros and cons of that system but it’s broadly the same as the one that has been in place since the introduction of the GST in 2000, notwithstanding the introduction of a 70% (now 75%) floor and ’no worse off guarantee’ in 2019-20 (which I’ll get to in a bit).

If Minns doesn’t want to go “into further debt”, he could always spend less. The NSW government is currently taxing more than it has at any time in its history, and expects revenue “to grow at an average annual rate of 3.4 per cent over the four years to 2026-27”, which is above its average inflation forecast of just over 3%. Poker machine taxes and toll road revenues are also conveniently excluded from the Commission’s calculations, to the benefit of these states.

Why NSW and QLD weren’t actually dudded

There’s a formula that determines how the GST is distributed each year. It’s all quite convoluted and based on a good deal of judgement, but for the 2024-25 financial year, the Commission concluded that NSW and QLD should receive less because:

“Both states have an increased capacity to raise coal mining royalties. New South Wales also has an increased capacity, relative to other states, to raise revenue from land tax.”

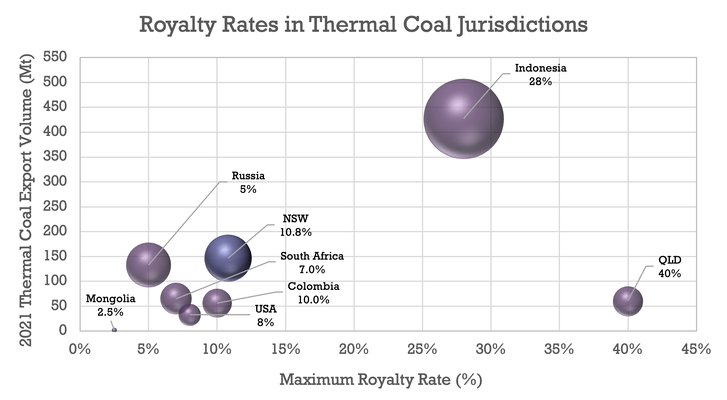

There is a bit of irony in this determination. You might recall that in 2022/23, with coal prices soaring on the back of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the leaders of NSW and QLD decided that their royalty rates were too low, with QLD in particular squeezing the sector for everything it could, hiking its maximum royalty rate to a world-leading 40%:

Those decisions raised considerable royalty revenue, for which those states are now paying the price in terms of a lower GST relativity.

The concept really isn’t that hard to grasp: because of the GST’s horizontal fiscal equalisation, when a state raises extra revenue and the other states don’t, at least some of it will be redistributed in subsequent years as part of the process to “reduce fiscal disparities between sub-central governments”.

The good news, depending on your perspective, is that following QLD’s royalty hike large miners such as BHP pledged never to do business there again:

“Given the negative impact on investment economics resulting from the change in coal royalty rates and the increase in sovereign risk due to the decision to raise royalties without consultation, we will not be investing in any further growth in Queensland.”

When QLD’s existing mines reach end-of-life and with nothing to replace them, they’ll collect fewer royalties, and the GST pendulum should swing back in their favour.

That’s actually one reason why VIC has done so well out of the GST in recent years: by banning everything from natural gas extraction to uranium mining, the Victorians have ensured that their state raises “a meagre $48 per person in mining royalties compared to a national average of $1,379”. Having fewer taxable commodities means the government has less ability to raise revenue, thus increasing their GST relativity.

Is the system broken? Perhaps. But it’s what we’ve got (thanks, Johnny H), and those are the political incentives it creates: because of the GST’s role in ensuring horizontal fiscal equalisation, states that ban certain commercial activities or otherwise do nothing to help facilitate private exchange do not have to bear the full fiscal consequences of their decisions.

WA and ScoMo’s “crude political calculation”

Now you might think that the biggest winner out of this system is WA, given it managed to negotiate a minimum relativity of 75c on the dollar yet still collects enormous iron ore royalties. Certain economists, such as Saul Eslake – who lives in Tasmania, which receives 80% more GST revenue than it generates – and Sydney’s Chris Richardson, have called the deal a “crude political calculation”:

“That represents a transfer of almost $40 billion from the federal budget to the Western Australian state government, the only government in Australia, and one of very few in the world, which is running and expects for the foreseeable future to run persistent budget surpluses, so that they can run even bigger ones.”

Is WA receiving more than it would without that “calculation”? Yes. But Richardson and Eslake are not being very good economists by ignoring the political incentives: if WA’s relativity was allowed to fall too low, what incentive would their politicians have to " slash green tape", or spend millions " to improve Western Australia’s digital capabilities to accelerate land development approvals and streamline delivery of key infrastructure projects"?

According to the Commission, WA’s relativity this year would have been 59%, so 16 percentage points below the floor and the lowest in the country. That’s probably high enough for WA’s politicians to avoid going full-VIC, i.e. making decisions that favour politically influential interest groups with the knowledge that if they mess up their economy badly enough, then the GST will be there to bail them out. But it wasn’t that long ago that WA’s relativity was at risk of falling below zero; even the most selfless politician would struggle to find the motivation to ensure productive businesses are able to thrive, and therefore pay the state considerable revenue, when most of it will flow to other states in subsequent years!

The fact of the matter is that even with ScoMo’s deal, at least 25% of the GST revenue generated in WA will still subsidise the other states and territories, such as Eslake’s Tasmania. And contra Richardson, the Commonwealth isn’t transferring “almost $40 billion from the federal budget” to WA, either: ScoMo’s deal doesn’t “cost” the federal budget anything, because the Commonwealth’s balance sheet is the chief beneficiary of very high iron ore prices.

In other words, when iron ore prices are high and WA’s relativity drops below 75%, the Commonwealth makes more than enough in additional iron ore-related corporate taxes to pay for the ’no worse off guarantee’ (ensuring other states do not lose out from WA’s floor) and keep some for itself.

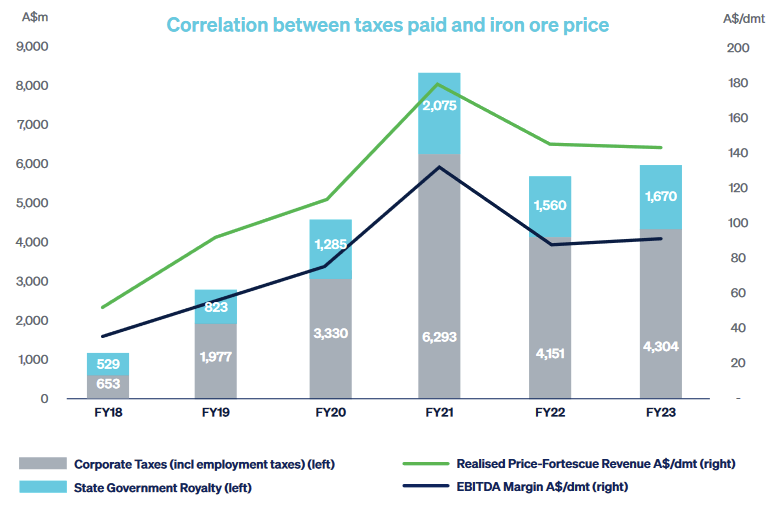

We can clearly see that by looking at the country’s most pure iron ore miner, Fortescue (notwithstanding its recent, loss-making spin-offs), which produces this helpful chart in its annual sustainability report:

The federal budget actually benefits when the iron ore price is high and WA’s relativity is below 75c (grey columns); it’s something that should be celebrated, not discouraged!

Really, the biggest winner out of the GST as designed is not WA but VIC, which will keep 97c on the dollar in 2024-25 because of its “lower capacity to raise mining revenue relative to other states”. That and the perennial claimant states, such as SA, TAS and the two territories, of course.

Funny how when you ban all sorts of commercial activities it limits your ability to raise revenue. The “crude political calculation”, which implemented a floor and benchmarked the fiscal equalisation component of GST redistribution against the stronger of NSW or VIC, rather than the state with the highest capacity to generate revenue (currently WA), actually made the whole process fairer: jurisdictions that encourage economic activity and are generally supportive of growth, which boosts their revenue raising capacity, are not punished for doing so to the same extent they were previously.

Instead of figuring out how to free up their private sector, allowing it to grow and then by proxy generate additional revenue for the government, our states would rather bicker over how the existing economic pie is cut. ScoMo’s deal isn’t perfect by any means, but at least it gets the incentives right by allowing states to keep some of the gains they helped support (or didn’t block in the name of some political calculation). In the long run, every Australian will be better off because the size of the economic pie, and every slice of it, will get bigger.

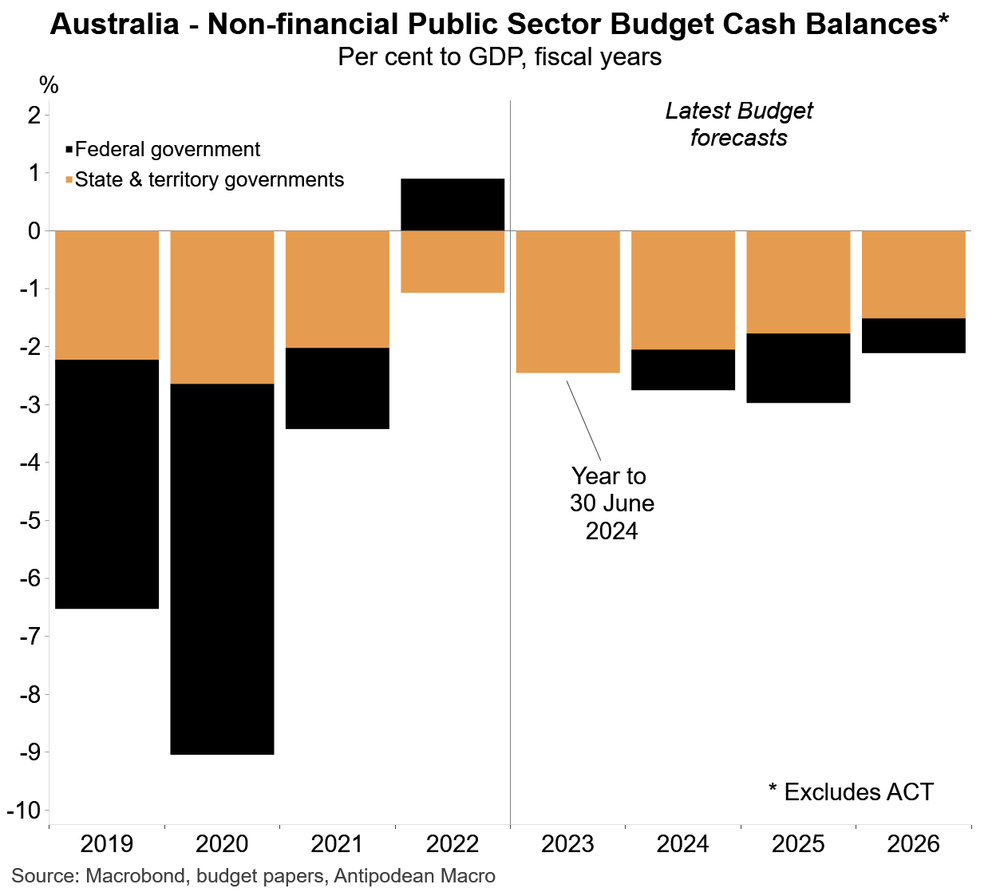

States are not good economic managers, so incentives matter

WA might be doing plenty to support certain sectors of its economy but that doesn’t mean I would go as far as calling it well-managed. There is no good reason, at all, for our states and territories – yes, including WA – to be racking up debt when the economy and inflationary pressures, both of which disproportionately benefit revenue over the expenditure side of the balance sheet, are this strong.

Responding to the GST claims made by NSW, WA Premier Roger Cook said that:

“The New South Wales government have to be able to demonstrate what all state governments need to do — manage your budget. live within your means, make wise investments. That’s what we’ve done and we’ll continue to do.”

Right. This is a Premier running a government that earlier this week had to go “cap-in-hand to parliament for an additional $1.3 billion on top of a previous billion-dollar top up” for a Treasurer’s Advance to meet urgent expenditure claims.

Does that sound like a well “managed” budget to you?

Then there’s the WA government’s own projections for net debt, which it expects to grow as a share of GSP from 6.4% this year to 10.0% in 2026-27, despite record royalty and GST receipts.

Cook will no doubt argue that the increase in debt is necessary for its record asset investment program, but that only begs the question: why are our state and territories “investing” so much in an inflationary, capacity constrained environment, with national unemployment near a 50-year low 3.7% (3.6% in WA)?

I’m no Keynesian, but the guy certainly had some bangers. I’m especially fond of his 1937 warning to Franklin Roosevelt that “the boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury”.

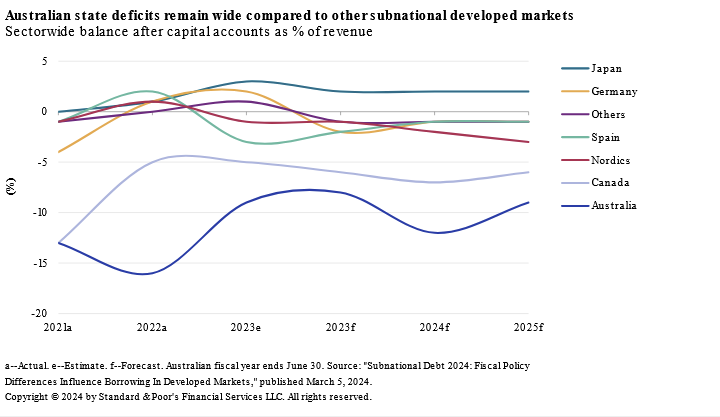

It’s time for our states and territories to rein it in, lest we have no fiscal capacity to react to future (inevitable) shocks. And if they can’t be trusted to do that themselves, then perhaps it’s time for some fiscal rules to force their collective hands. According to ratings agency SP Global, the lack of such rules has led to a relatively large “revenue-expenditure imbalance for Australian states and territories”, and is a “key downside risk to our institutional framework assessment”:

Unlike other advanced economies, our states are “not bound by external fiscal rules… [which] bestows on them more flexibility to invest and maintain sizable after capital account deficits”.

The problem is a lot of that “investment” (public sector speak for “spending”) probably won’t turn out all that great given all the cost overruns because they’re doing it in a capacity constrained economy! And don’t get me started on the handouts, such as the WA government’s $250 payment per school student, which are pure political candy.

Personally, I think our states could use some fiscal rules, handcuffing them during the good times so that when the next shock rolls around we actually have some fiscal firepower to respond to it. Currently, only NSW has any kind of fiscal target in its legislation, but it’s not even worth the paper it’s printed on – there are no penalties if the government misses them.

We’re now in a world where money is no longer free, and governments should only spend if they’re willing to raise the taxes they need to pay for it. They need to stop issuing more debt than people will be willing to hold, because if they don’t then the inflation we had in 2022-23 won’t look all that bad compared to what could be in store for us after the next crisis…

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!