It's time to break a few eggs

This is why we can’t have nice things. Last week, federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek decided to block Victoria’s Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal, a port that would have been used for the state’s planned offshore wind industry, citing the damage it would cause to wetlands, including:

“…irreversible damage to the habitat of waterbirds and migratory birds and marine invertebrates and fish.”

One of the birds that frequents these wetlands is the sharp-tailed sandpiper, a bird that was declared ‘vulnerable’ on 5 January, just days before Plibersek’s decision. The sharp-tailed sandpiper, like the critically endangered eastern curlew and curlew sandpiper that also wade there, migrates from its breeding grounds in Siberia each year, directly over the Pacific via Alaska (juveniles) or down through Asia (adults). They’re spotted all over Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, and aren’t picky eaters, with the sharp-tailed sandpiper showing a willingness to “scoff aquatic worms, insects, molluscs, crustaceans and even seeds”.

Presumably if they lost part – 92 hectares, to be precise – of their 60,000 hectare Western Port wetland, it wouldn’t be a huge issue – they would just have to spend their winters in the 99.85% of the remaining wetland, or one of the other 39 sites in Australia where they have been spotted in large numbers. According to Bird Observer:

“Sharp-tailed Sandpipers are a flexible species which utilises a broad spectrum of wetlands and thus may be able to adjust to the vicissitudes of climate change and anthropogenic habitat alteration.”

The key risk to these wading birds isn’t their winter wetland getaways in Australia but the treacherous return trip over China and Korea they have to make to get here:

“Habitat loss on the Yellow Sea staging grounds is probably the primary threat to the species, with loss of stopover sites thought to be responsible for shorebird population declines on the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (Amano et al. 2010, Yang et al. 2011). It is estimated that up to 65% of intertidal habitat in the Yellow Sea has been lost over the past 50 years, with the rate of habitat loss estimated at >1% every year (Murray et al. 2014). This scale of habitat loss is predicted to continue owing to growing populations around the Yellow Sea.”

A sign of a deeper issue

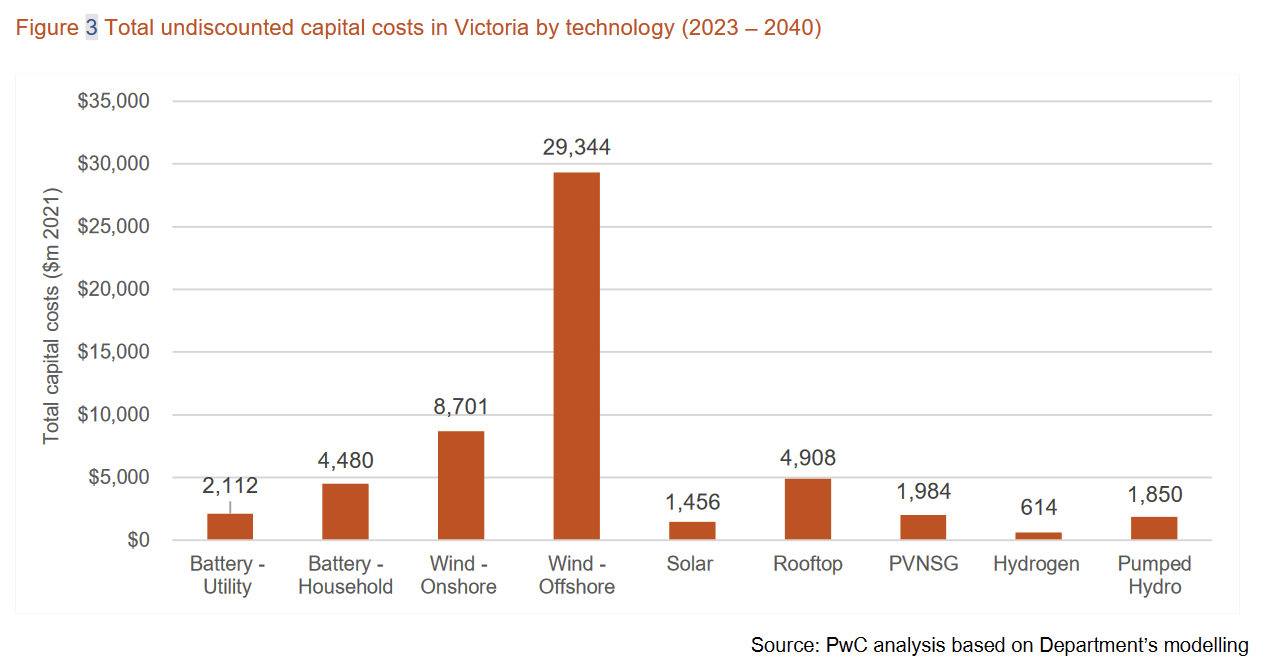

But the point I want to make isn’t about Victoria’s wading birds. It’s about the desire for state and federal governments in Australia to transition to net zero and the trade-offs that need to be made when building, transmitting and storing a lot of renewable energy in a short period of time. For instance, in Victoria new offshore wind is central to its plan of reaching a renewable energy target of 95% by 2035.

But the problem with wind is that even though it’s green, it causes potentially material disruptions to habitats. Advocates for renewables recognise the conflict, but never with an acknowledgement of trade-offs. For example, Kelly O’Shanassy, the chief executive of the Australian Conservation Foundation, said Plibersek “made the right decision”, and:

“We need to build renewables fast and there are going to be impacts to nature from all developments. But we need to make sure the most important areas with high conservation values are off limits to all developments, including renewables. We don’t need to choose between nature or renewables.”

An issue that governments are going to increasingly encounter as they try to ramp up their investment in renewables, specifically in wind but also for solar and hydrogen, is a lack of areas that don’t have “high conservation values”, however defined. And not just when those projects jeopardise birds; independent MP Allegra Spender, in her response to Plibersek’s decision, not only wanted to distinguish between the type of project but also asked for the “broader impact” to be considered:

“Every single project whether it is a renewable energy project or another mining project needs to look at its environmental impact as well as the broader impact on the economy and climate.

…

But what I want to see out of the environmental rules at the same time is to make sure we are not looking at those same environmental laws and saying, ‘you know what, keep on approving coal mines, keep on approving gas mines’.”

Spender is trying to have her cake and eat it too: she’s asking for environmental laws that are tough enough to block all coal and gas mines, but loose enough for new wind farms (just not in Victoria’s Western Port Bay area, though). But that’s not the way rules work. Either the environment is sufficiently protected by our laws, or it’s not; the type of project shouldn’t matter, unless it’s explicitly banned or exempted.

NIMBYism strikes again

But more troubling was Spender’s idea that a project’s “broader impact” is analysed before approval is granted. One of the reasons we have a housing crisis is because of an excessive concern about the “broader impact” – expressed most vocally by those who, through good fortune of birth, managed to buy when land was relatively plentiful – with zoning laws restricting what people can build to the point where it’s hard to build anything. In NSW, wind farms have already been caught up in the web of zoning, thanks to “a new ruling that requires a 2km setback from any building on any adjoining property”:

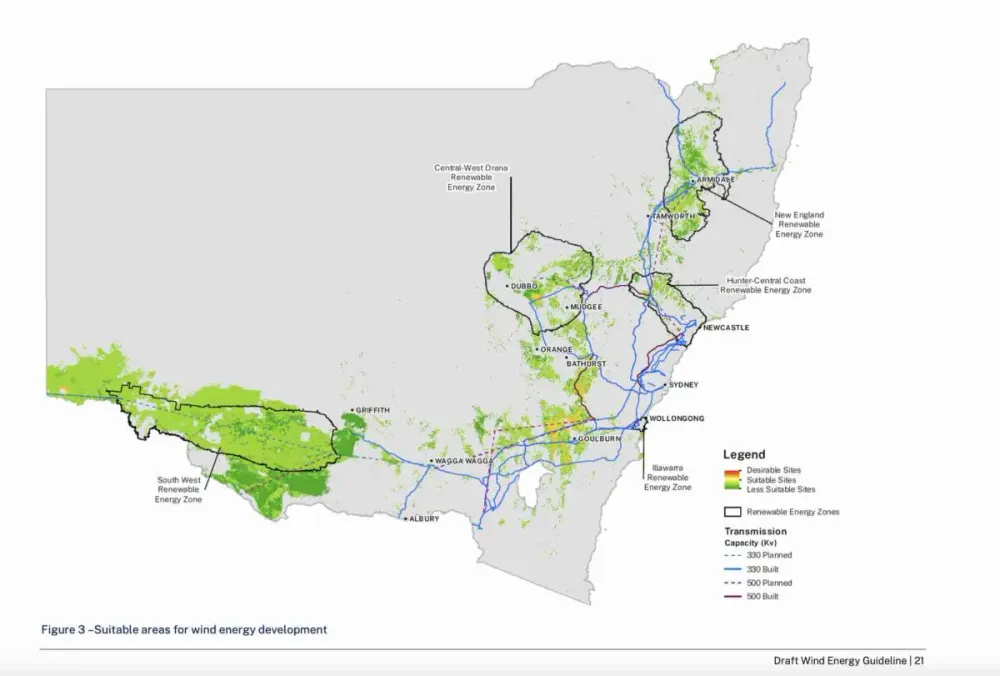

“The NSW department of planning, which has only approved one new wind project in the last three years, overlaid this new guideline on a map of NSW, resulting in vast tracks of the state being deemed “less suitable”, and only a few isolated spots deemed “desirable” for new wind projects.

…

Stephanie Bashir, from Nexa Advisory, says the NSW wind map needs to show more “desirable” locations, given NSW is aiming to have 14GW of renewable energy by 2030 and, according to Premier Chris Minns, the state is currently way behind on those plans. “How do you scale up renewable energy production if your starting point is identifying virtually no “desirable” locations to host wind farms? It doesn’t add up,” Bashir said.”

The NSW government’s map is like something out of Where’s Wally – see if you can even spot the red “desirable” sites:

The inability to build wind farms led the International Energy Agency (IEA) to revise down its renewable projections for Australia by over 10% in its January 2024 report, “due to slow project progress and ongoing policy uncertainties”. It warned that the low-hanging fruit of solar PV – “the primary source of growth in Australia in recent years” – has been saturated, creating “grid integration challenges” that need to be resolved before any more progress can be made. And the sun doesn’t always shine; to fully transition to renewables you need complementary power sources that work when the sun doesn’t, such as wind, and adequate storage (i.e., a lot of batteries).

Uncomfortable trade-offs still have to be made

Unfortunately for the proponents of renewables – but especially wind – a lot of the time the best places to build the stuff also happens to be where wildlife tends to hang out. And people. And a lot of other things that might get caught up in any assessment of “broader impacts”. If we followed Spender’s logic to its inevitable conclusion, we’d reach a point where there will be so many people that effectively have the power to veto a project that we end up with a map that has no acceptable spots to build anything at all. NSW Nationals Leader Dugald Saunders recently spelled out how it’s going to unfold:

“There’s no doubt renewables, and I think every type of renewable – whether its wind or solar, pumped hydro being looked at now as well – we’ve come to a different point now where people are really actively looking at these projects again now and thinking well maybe I don’t want that near me.

So, for proponents of renewable energy, there has to be absolutely a social license; there has to be community consultation properly, and we’ve got cumulative impact that’s happening.”

Those opposed to renewable projects, whether ideologically or for NIMBY reasons, are going to slow progress towards net zero by using the same tools environmentalists have been using for decades to slow and raise the cost of fossil fuel projects. Noise, aesthetics, tourism, recreation, wildlife, habitats, danger, lightning, their way of life – you name it, and you can be sure it will be trotted out in opposition of these projects during “community consultation”, often without any evidence at all. They don’t have to be right: they just have to delay projects for long enough to make them prohibitive.

If nothing is done to prevent such tactics, which create huge costs for investors and governments in terms of uncertainty and potential delays, we’re going to be forced to run what’s left of our old, dirty and dilapidated coal-fired plants (who would invest when the government has effectively ordered them to shutter) for a whole lot longer than necessary. It’s always about trade-offs, and when someone blocks green energy in their backyard, they’re probably creating pollution in someone else’s.

The way out of this quagmire

But the good news is that there’s still a way out. To achieve their renewable energy goals, Australian governments – starting with the federal government, given we have two, overlapping levels of environmental protection laws – are going to have to ask themselves what’s more important: saving a few birds, or acknowledging we may need to break a few eggs to achieve much more significant benefits?

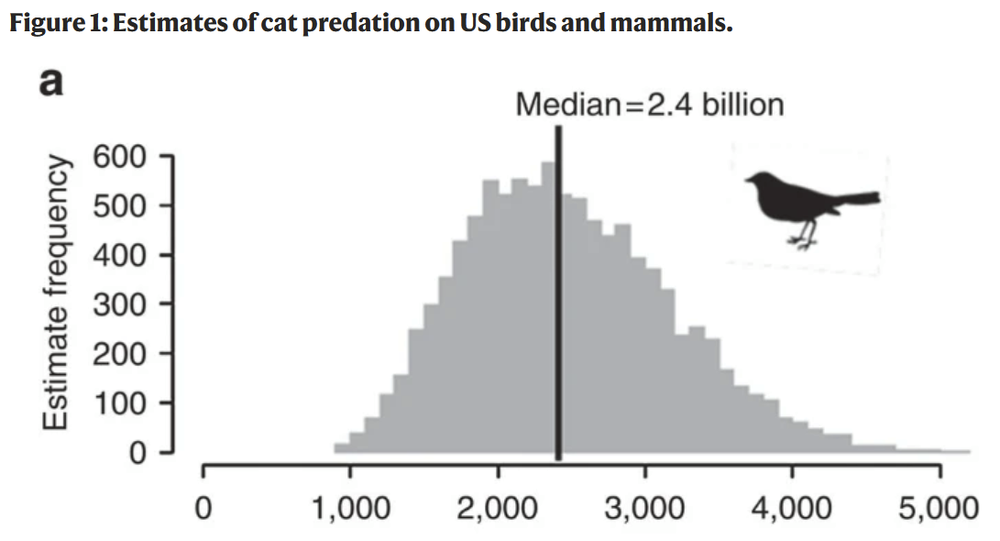

They need to start thinking in terms of trade-offs, and that might mean sacrificing some habitats in the name of clean energy. In net terms, birds might even be better off: more renewables will mean less pollution (especially from coal, Australia’s fossil fuel of choice), which at least one study found kills something like 19x more birds per gigawatt-hour of electricity produced than wind turbines. A more recent study in Environmental Science & Technology found that “Wind turbines do not have any measurable impact on bird counts”, even for large birds such as hawks, vultures and eagles. The same could not be said for shale oil and gas projects, which “reduces subsequent bird population counts by 15%”, and by up to 25% when drilled in “important bird areas”.

One irony of this whole saga is that we seem perfectly fine killing birds in other ways, such as with tall buildings and house cats. But we already have tall buildings and house cats, so for some reason people don’t seem to care. In fact, I’d hazard a guess that many of the people who supported Plibersek’s decision are also against wind farms because of the risk to birds, yet still own cats and live in apartment buildings.

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t know whether Victoria’s Renewable Energy Terminal, to be located on the fringe of one of Australia’s 67 Ramsar wetlands sites, was the right spot for the port; perhaps it could be built at similar cost elsewhere, with even less damage done to wildlife.

My point is much broader: the whole process has shown a disturbing lack of acknowledgement about the importance of considering trade-offs when thinking about the environment. The costs are always mentioned, but rarely do the benefits get a shout out. That mentality will need to change if our governments are to have any hope of reaching their net zero targets. And yes, that might mean breaking a few eggs along the way to save many more in the long run.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!