It's time to end the Future Fund

Believe it or not but last week the US Presidential race – a battle of bad policy – threw up yet another bad policy. This time it came courtesy of Donald Trump, who proposed the US government establish a sovereign wealth fund:

“Why don’t we have a wealth fund? Other countries have wealth funds. We have nothing”, Trump said during his speech to The Economic Club of New York, adding that the US fund would be financed by tariffs “and other intelligent things”.

…

“We will build extraordinary national development projects and everything from highways to airports to transportation infrastructure… We’ll be able to invest in state-of-the-art manufacturing hubs, advanced defence capabilities, cutting-edge medical research and help save billions of dollars in preventing disease in the first place”, Trump said. “And it is many of the people in this room who will be helping to advise and recommend investments for this fund”.

If I understand that correctly, Trump is proposing to raise taxes on consumers (tariffs), use those taxes to fund a sovereign wealth fund that invests in “national development”, presumably in projects with either low yields or high risk, which the private sector would typically avoid, for the benefit of economic and financial advisors who will earn a commission from every decision the fund makes.

What he’s proposing isn’t without precedent. We have our own sovereign wealth fund in Australia called the Future Fund, established in 2006 back when the federal government used to run budget surpluses and wanted to squirrel some of it away to pay for the unfunded pension promises it made to public servants that wouldn’t come due for many decades.

Plenty of other countries have sovereign wealth funds too, usually to save some windfall revenue from the sale of scarce natural resources (e.g. Norwegian oil), or to borrow and invest in assets on behalf of the government (e.g. Singapore).

But they only really work when the country in which they reside runs structurally balanced budgets, as in Norway and Singapore. A sovereign wealth fund represents a choice between investing excess revenue in something that will give future citizens some benefit, or just giving it to current citizens. For me, it depends on how the revenue was raised. An oil windfall? Bank some of it for future generations. Excess taxes or borrowing? Just give it back to the people.

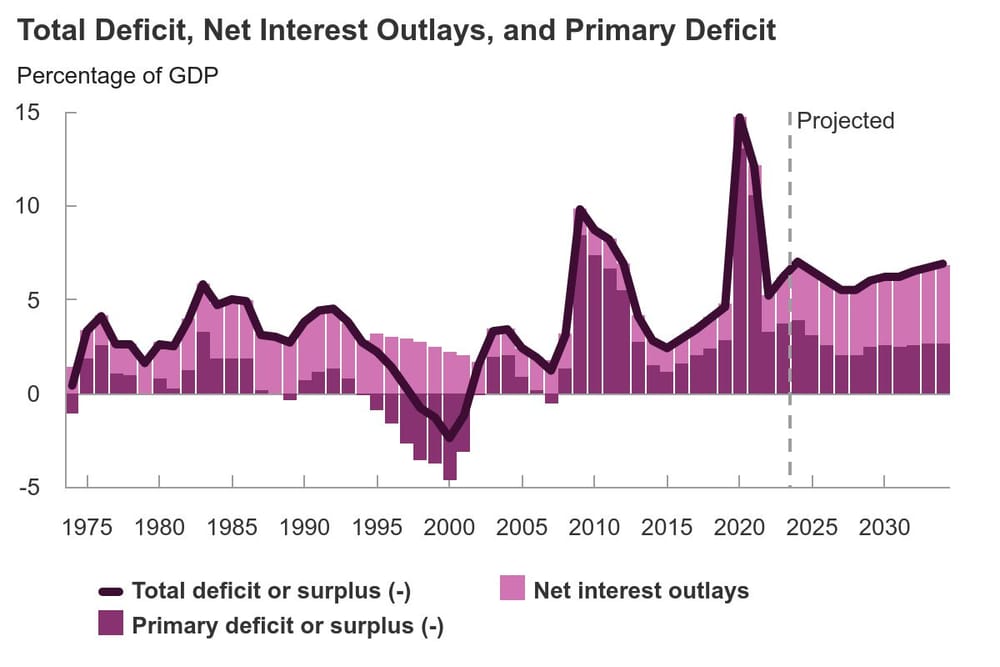

Such a choice doesn’t even have to be made in the US, which has neither windfalls nor once-off commodity revenue, and in fact runs massive budget deficits:

If all of those deficits were being used to invest in productive assets, as Singapore’s debt mostly does, then it wouldn’t be too much of an issue – its sovereign wealth fund is more of a means to ensure politicians don’t misallocate resources.

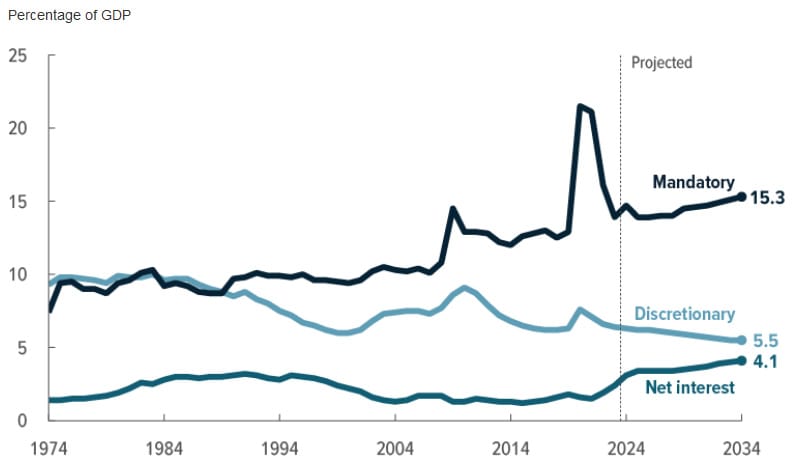

But it’s not. The US has a huge, unfunded liability problem and is mostly adding to debt to pay for current expenditures on things like Social Security and Medicare – so-called “mandatory” spending – not nationally significant infrastructure, which would fall into the “discretionary” category:

So, not only should the US avoid establishing its own Future Fund at least until it gets its fiscal shop in order, but there’s also a decent case for Australia to liquidate its own.

It hasn’t performed all that well

The Future Fund received its initial endowment on 5 May 2006 but has received several top-ups since then. To keep it simple, I’m only going to use the initial $18 billion and the nominal annualised return since inception figure provided by the Fund for the period 2005-06 to 2022-23 of 7.8%, which brings the fund to $64.5 billion today.

That’s pretty impressive. If the Howard government had instead invested that amount in the ASX200 net total returns index, which had a nominal annualised return over the same period of 6.6%, it would only be worth $52.9 billion today.

But the catch is the Future Fund receives special privileges that normal investors do not. For example, it’s exempt from income tax, both in Australia and on most of its overseas investments (under “the principle of sovereign immunity”). If it weren’t exempt, its returns would be considerably lower: the ASX200’s long-run annual dividend yield is 5.6%, two thirds of which are taxable (the other third is offset with franking credits to prevent double taxation). Using the corporate income tax rate of 30%, that means at least 1.1 percentage points of its total returns, or 16.7% (1.1/6.6), are lost to tax each year.

If we take that share off the Future Fund to level the playing field a bit, its nominal annualised return since inception falls to about 6.5%.

In other words, the Future Fund’s returns – if they weren’t exempt from tax – under perform what a simple ASX200 index fund would have returned over the same period. The difference would be even greater if the funds were invested in the S&P500, the nominal net total annual returns of which were 10.5% over the same period. Add the decline in the Australian dollar since inception, and the annual returns of that option grow to 11.4%.

That’s not a criticism of the Future Fund’s managers; it’s generally a feature of these funds to return less than an index, given they have to pay those managers. In the Future Fund’s case, its operational costs are over 1% of funds under management, as it moved from being a low-cost vehicle mostly holding things like the Telstra stock it inherited to a more active asset manager.

It’s always going to be tough to beat an index when 83 employees are being paid over $235,000 annually. And it’s not like the government is even pretending that the Fund is anything but jobs for mates these days; over the past decade it has been chaired by former federal Liberal and Labor politicians, Peter Costello and Greg Combet, neither of which are known for their investment pedigree.

It’s not 2006 any more

Other than the Future Fund’s relatively poor performance, Australia’s fiscal position has changed a lot from when we were banking surpluses to feed a sovereign wealth fund.

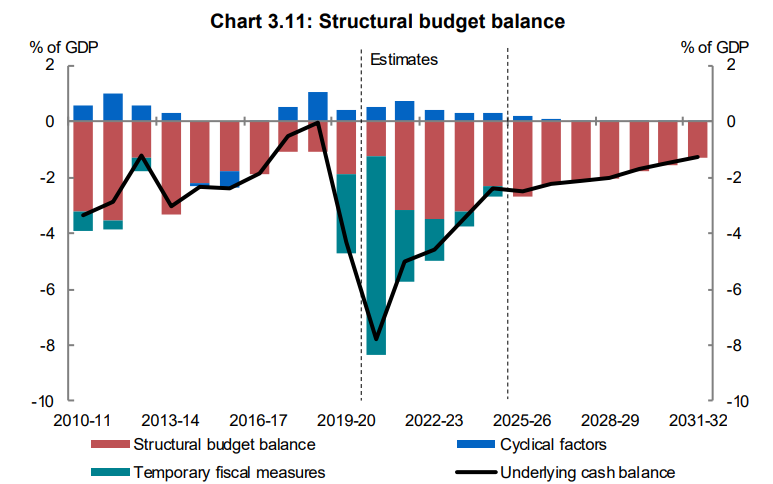

Today, the federal government is deeply in debt ( over 30% of GDP), and runs persistent structural budget deficits. The structural part of the deficit means we’re going to need to see some kind of policy shift in how we collect revenue (e.g. tax reform) or what we’re spending on (e.g. entitlement reform) if we’re any hope to balance the budget again in ’normal’ times:

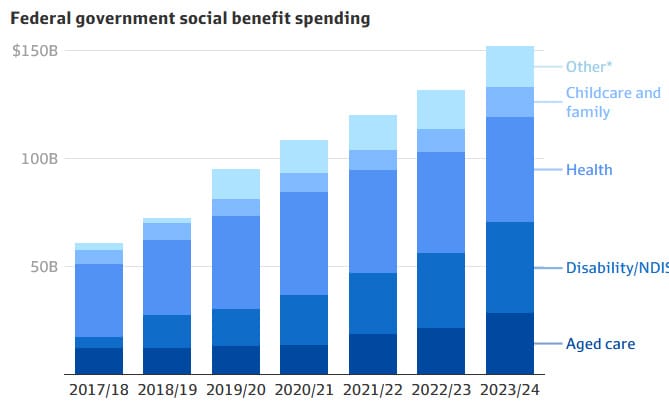

I’ve written before about the need for tax reform. But on the spending side, it turns out we’re increasingly borrowing to pay for current expenditures on things like social benefits, not nationally significant infrastructure:

Not only is that adding to inflation, but it’s worsening the structural deficit; it’s unsustainable. It also means we probably can’t afford to carry a Future Fund that returns less than ASX200 and is no longer using “saved” money: for every dollar of assets at the Future Fund, that’s one more dollar that the federal government has to borrow.

The Future Fund is worth around $220 billion, and a proxy for the government’s cost of borrowing – 10-year bond yields – are a touch over 4%. Put the two together and the opportunity cost of the Fund is at least $10 billion per year.

The future is now

The Future Fund was created when the fiscal sun was shining, assets were being sold off, and so it made sense to put some cash away to shift some benefits to the future to cover obligations politicians at the time were making.

However, we’re now deep in debt and so having a sovereign wealth fund is basically just the government borrowing money to make bets with it. There is of course an argument to do that; equities earn more than government bonds, so a well-managed, debt-financed sovereign wealth fund could be in the nation’s interest.

But stocks are volatile – the equity premium only exists because of the extra risk – and I don’t know about you, but having bureaucrats taking punts on the stock market isn’t something I’d put in the “public good” basket. In fact, the closer we get to the government’s superannuation liabilities falling due, the less need there is for the Future Fund even if you believe its original purpose still holds: the last thing we’d want is for equity values to plummet at precisely the time the government needs to start drawing on it to pay former bureaucrats’ pensions.

The fact of the matter is that every dollar in the Future Fund is a dollar that you could be using, or the government could be using to pay off some of its debt, reducing the amount it will have to tax you in the future.

It’s time to end the Future Fund.

ADDENDUM: A careful reader pointed out that although the Future Fund was initially endowed in 2006, it still held over 75% of its portfolio in cash as of January 2008, i.e. just before the Great Recession stock market crash. By 30 June 2010, its cash balance had fallen to 13%. In other words, because it was so fortuitous in its entry point, the Future Fund has likely underperformed the ASX200 by even more than I estimated in this post.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!