Jim Chalmers' Nixon moment

I thought I’d write another post on last week’s Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) decision to leave rates on hold. Why? Mostly because there was so much in the statement that I couldn’t possibly cover it all on top of the market rout (and subsequent recovery!). But also because I want to discuss the political economy of the RBA, which is becoming more and more relevant in these tumultuous times.

The federal government and RBA are seemingly at loggerheads. For example, take Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s (Albo) response to the RBA’s decision:

Natalie Barr: Prime Minister, the RBA has indicated government spending is making it more difficult to get inflation under control. Are you concerned all of your spending is adding fuel to the fire?

Albo: No, we’re making sure that our spending is designed in a way that continues to moderate inflation… We’re making sure that they’re getting that cost of living relief, but we’re doing it in a way, so it’s designed to put that downward pressure on inflation at the same time.

Here was Treasurer Jim Chalmers, who was asked a similar question:

“Budget spending is not the primary determinant of prices in the economy, but we can be helpful – and we are being helpful – with the design of our cost-of-living policies which help us get back to targets sooner.”

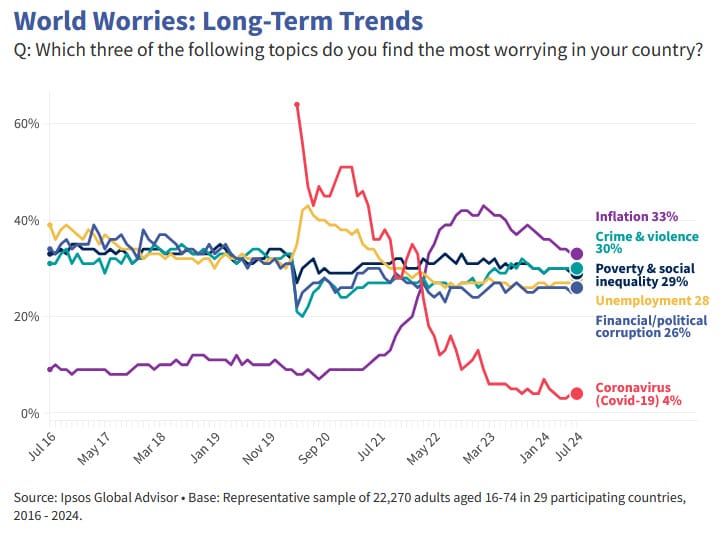

These statements are contradictory to what the RBA told us last week and I think they’re a good example of the political way of thinking. Politicians have many incentives, but none is greater than the desire to be re-elected. And inflation is deeply unpopular with the electorate when it rises beyond a certain rate, so it very quickly moves to the front of political minds:

The problem is that while there’s a good theory explaining how governments can raise inflation with debt-financed spending, politicians know that reducing such spending is also unpopular. So they attempt to have their cake and eat it too by spending in ways that they claim will “put that downward pressure on inflation”.

What’s not said is that when Albo and Chalmers speak of “inflation”, they mean short-run measured inflation: the consumer price index (CPI). They can stand up and, with a straight face, say that “Treasury says this will reduce inflation”, and it’s technically not a lie. But they’re also not being truthful; it’s a classic example of what Jagdish Bhagwati observed in a 1987 paper published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

“In economics, consensus is produced by sharpening differences; in politics, by obfuscating them.”

Economists define inflation as an increase in the general level of prices, which can be restated as a decrease in the purchasing power of money relative to goods and services. A slowdown in the CPI’s rate of growth – an imperfect measure of inflation – does not necessarily mean inflation has slowed.

We need to know why growth in the prices measured by the CPI slowed.

In this case, growth in the CPI will slow not because of any change in the rate of inflation, but because the government is rather blatantly targeting its components to make it look like inflation is falling.

Goodhart’s law strikes again

The most recent example of many such attempts to distort the CPI was in childcare:

“The Albanese government will fund a 15 per cent, $3.6 billion pay rise for childcare workers over the next two years on the proviso their employers agree to limit fee increases until after the election, and accept longer-term, union-negotiated pay deals for their workers.”

Regardless of the merits of such a decision, it will add to inflation because those higher wages are going to come from subsidies, and as it’s very labour intensive work, they likely won’t be offset through higher productivity. That’s a choice: in its 2023 draft report into the sector, the Productivity Commission said that wages in the childcare sector – which are heavily regulated – had to rise or the industry was at risk of staffing shortages. However, the “decision for governments” was whether that should occur through higher fees (i.e., paid by parents using the services) or additional government subsidy.

Higher fees would be neutral for inflation: a transfer from parents to childcare workers. A government subsidy, however, adds to inflation because the economy is capacity constrained and it’s being financed with debt. So, it will increase overall demand, i.e. result in more money chasing the same number of goods and services. It will reduce the purchasing power of the dollar relative to goods and services.

But the trick Albo is pulling here is mandating that fee increases be limited over the next 12 months for childcare centres to be eligible. Although trick is probably not the right word to describe it; according to Employment Minister Murray Watt, it’s a stated goal:

“To be eligible to receive this extra money for pay, childcare centres will need to limit any fee increases to 4.4 per cent over the next 12 months. So there’s actually a measure in this policy to ensure that it isn’t inflationary.”

The way the ABS measures childcare in the CPI is by looking at the out-of-pocket costs for families. Essentially, the government is doing everything it possibly can to make sure that childcare costs don’t meaningfully rise until after the election.

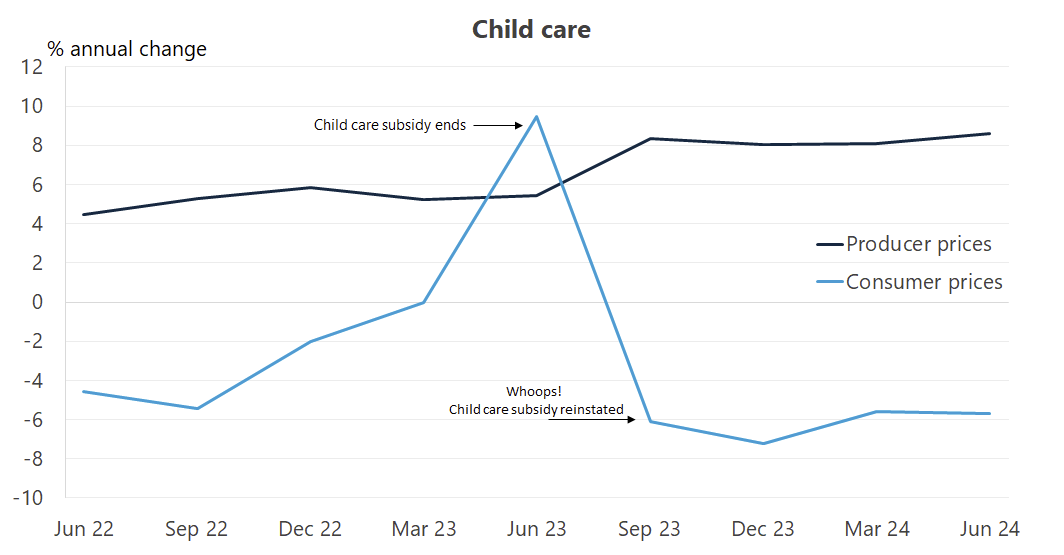

And the plan will work, too. This is a sector where measured consumer prices have been falling for many years due to various government subsidies:

But the actual inflation is already baked in – just look at childcare producer prices, which are growing at over 8% annually. The inflation is there, it just won’t be captured by the CPI until 2025 at the earliest.

Basically, Albo is trying to hide the political hot potato of rapidly rising childcare prices, while ensuring that childcare facilities can still pay competitive wages to attract and retain staff. In essence, he’s reducing measured inflation while making actual inflation worse. Such antics fall into the realm of Goodhart’s Law, which is often stated as:

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”.

In this case, the government’s focus on reducing the CPI is leading to the manipulation of its components, rather than addressing underlying inflationary pressures. In doing so, they’ve made the headline CPI a poor measure of inflation.

Political pressure can be costly

Our governments – federal, state and territory – are all spending far too much for where we’re at in the business cycle. There’s no question they’re making the RBA’s job more difficult; the fact that the central bank was forced to finally admit as much is telling: the RBA is ultimately a political organisation, which owes its independence to political decision makers, so it was no doubt a big decision to publicly call out its master.

I’m just thankful that the Australian and global public has grown so accustomed to an independent central bank, because in practice there’s nothing stopping Chalmers from taking control of the RBA; he just knows that doing so would be political suicide.

But that doesn’t mean the government can’t influence the RBA in other ways. Chalmers has already appointed two former union officials to influential monetary policy-setting positions, and has been accused of trying to use the recent review of the RBA as an opportunity to “stack out the board” with puppets. Such actions raise concerns about potential political interference in monetary policy – an issue that has historical precedents.

One notable example of such interference comes from the US in the early 1970s. Former US President Richard Nixon – who resigned in scandal 50 years ago last Thursday – sought to influence the US Federal Reserve (Fed) for political gain, knowing full well that stacking the Fed’s board might get him the easier monetary policy he so desperately craved:

“I’ve told [Treasury Secretary John] Connally to find the easiest money man he can find in the country. And one that will do exactly what Connally wants and one that will speak up to Burns… and Connally is searching the god damn hills of Texas, California, Ohio. We’ll get a populist Senator [sic] on that Board one way or another… If you know of someone that’s that crazy let me know too… I want a man on that board that I can control. I really do. Basically that Connally can control.”

Research suggests that Nixon’s pressure on Fed chair Arthur Burns led “to a 100 basis points lower interest rate”, which caused “a 5% higher price level after 4 years”. His motivation was the forthcoming 1972 election:

“Evidence from the Nixon tapes, recently made available to researchers, clearly reveals that President Nixon pressured Burns, both directly and indirectly through Office of Management and Budget Director George Shultz, to engage in expansionary monetary policies prior to the 1972 election.

…

[The] monetary stimulus helped to boost the economy in time for the 1972 election, helping to deliver Nixon’s landslide victory. However, the excessive aggregate demand stimulation prior to the election created serious problems for the economy that took nearly a decade to resolve.”

To be clear, I don’t think Albo and Chalmers are knocking down RBA governor Michele Bullock’s door begging for easy money. But they’re not all that far off. Nixon covered up his inflationary mishaps with price controls, starting in August 1971, i.e. 15 months before the general election. In a sense, Albo and Chalmers are doing the same: they’re temporarily hiding the inflationary impacts of their policies by manipulating measured prices ahead of the 2025 election.

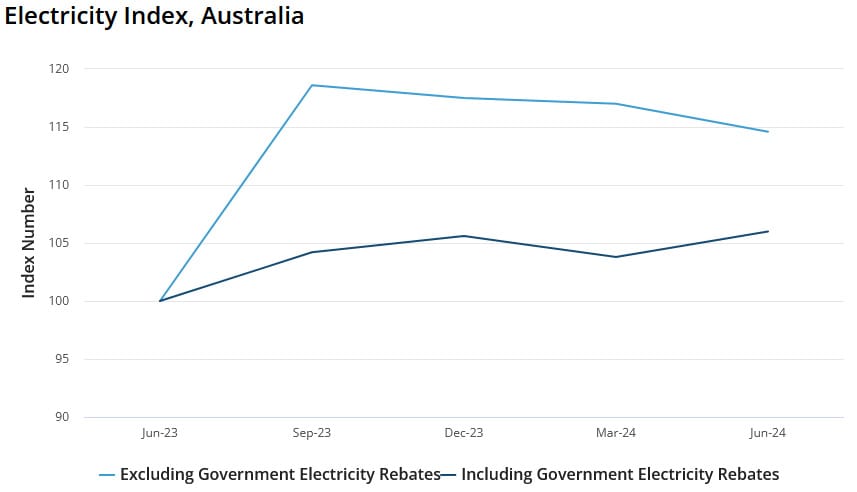

The good news is that our statistical agency has come a long way since the 1970s and is able to look through such distortions, providing helpful insights like this:

So too does the RBA, which explicitly said it expects measured inflation to temporarily fall because of the government’s cost of living payments, only to bounce right back up because they haven’t actually reduced inflation:

“Headline inflation is likely to be lower than underlying inflation in the near term, largely due to the Australian Government’s temporary measures to reduce the cost of living, and then increase as these measures unwind.

…

Paying attention to underlying measures makes sense because headline inflation can be affected by large swings in the prices of individual items that are unrelated to broader conditions in the economy. Such swings can occur for several reasons, including… a change to a government policy that results in a large change in the price of a particular item.”

So far, RBA governor Michele Bullock looks to be avoiding becoming the next Arthur Burns, who after pushing back for years eventually caved to Nixon’s demands and ended his Fed tenure in disgrace. I only hope Bullock can continue to resist the inevitable political pressure as the election draws nearer and the polls narrow, and set monetary policy based on what’s economically appropriate, not what’s politically convenient.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!