Lessons from the Old Country

The British brought a lot of good (and bad) things to Australia, but perhaps the common law – an institution that governs how we interact with each other to this day – tops the good list. Back in 1914, American legal scholar Roscoe Pound famously wrote that:

“Perhaps no institution of the modern world shows such vitality and tenacity as our Anglo-American legal tradition which we call the common law. Although it is essentially a mode of judicial and juristic thinking, a mode of treating legal problems rather than a fixed body of definite rules, it succeeds everywhere in moulding rules, whatever their origin, into accord with its principles and in maintaining those principles in the face of formidable attempts to overthrow or to supersede them.”

But while durable, institutions can decay, especially when the political incentives are to find ways around them. These days not all is well in the Old Country, and I think there are some lessons Australia can learn about what not to do if we want to avoid a similar fate.

Thankfully for us, the British are much further along the road to institutional decay than Australia, largely because it’s the source of many of the bad ideas that caused it, and – as the proverb goes – a fish rots from the head down. But Australia is also the “lucky country”, endowed with natural resources, vast amounts of space, and a more favourable climate, allowing us paper over many similar deficiencies – at least temporarily.

The state of Britain

Plenty has been written about how bad the economic situation in Britain has become, and why. So, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise to anyone that after 14 years in charge of public policy, the Conservative government was recently turfed in favour of a new Labour government promising to reform problematic sectors such as housing.

Will it ‘fix’ the UK’s broken housing market? I’m doubtful, given that it appears to be “tinkering within the current system, rather than attempting the sort of big change like introducing a zoning system that has helped increase supply significantly in New Zealand and some US cities”.

Sometimes you just need to rip it all up and start over. A new study of British stagnation pointed the finger squarely at the government’s prohibition “on investment in housing, infrastructure and energy” as the cause of its lacklustre labour productivity: GDP per hour worked has grown by 7% since 2007, or just 0.4% a year. For context, Australia – which has seen virtually no labour productivity growth over the past decade – still increased GDP per hour worked by nearly 15% over the same period, double the rate of the UK.

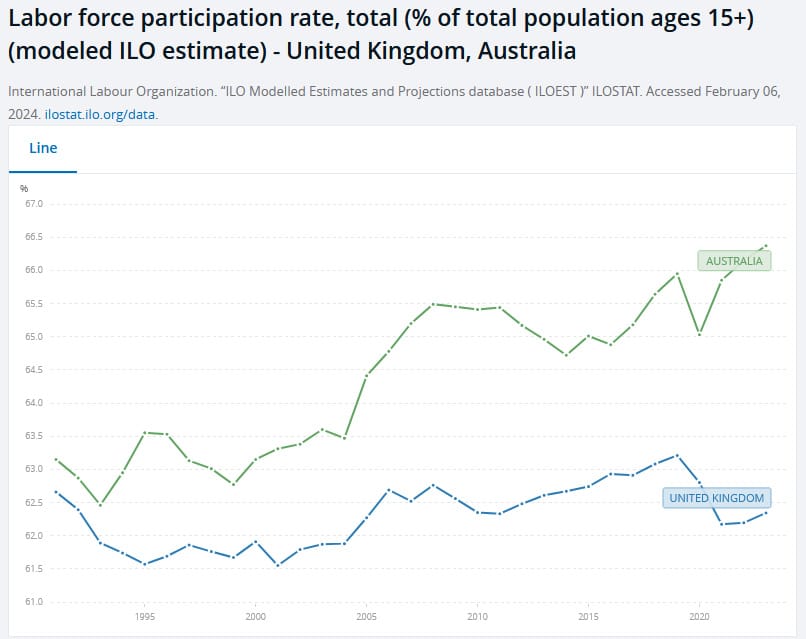

While Australians have made up for their lack of productivity by working more hours to maintain living standards (hardly sustainable!), the UK has not, with participation rates back at 1992 levels, never recovering from the Covid shock:

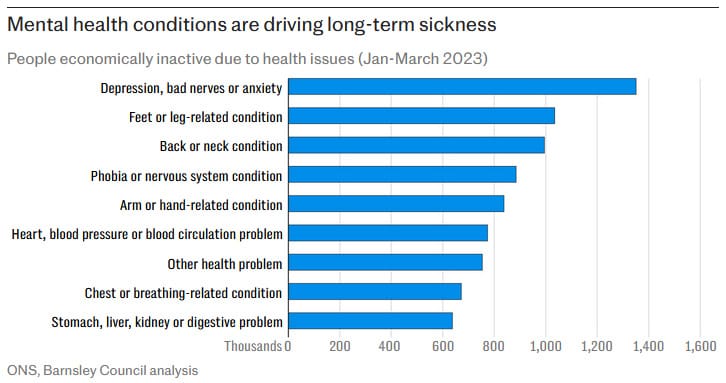

The Poms are also less healthy than they once were, and it’s getting worse. Alcoholism is on the rise, and amongst the young “tens of thousands are moving straight from university into long-term sickness… attributed largely to an ‘acceleration’ of mental health conditions post-Covid”.

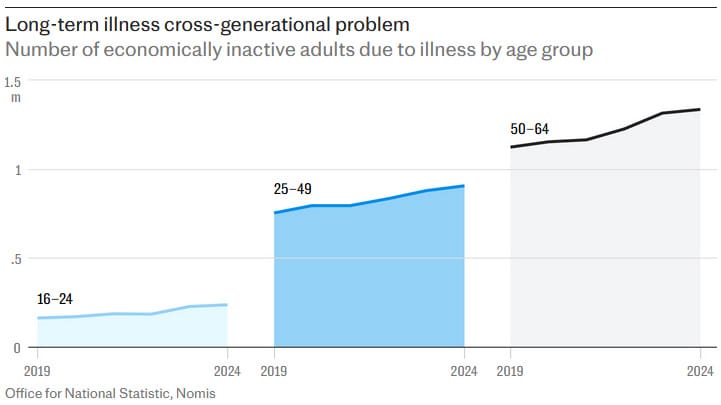

In older age groups, the “heightened loneliness and depression suffered during the lockdowns by this cohort, as well as a decrease in exercise and – again – increased drinking”, has persisted into 2024. Alcohol-related deaths are at all-time highs, and the number of “economically inactive” adults continues to rise:

If you combine all of that with the country’s soaring electricity costs, inability to build homes where the good jobs are located, and extremely expensive (by global standards) transportation infrastructure, then Britain’s stagnation shouldn’t really be a surprise. Decline through institutional decay is a choice, and it’s the one Britain’s politicians have been making since at least the Great Recession, although its roots go all the way back to 1947.

Planning to fail

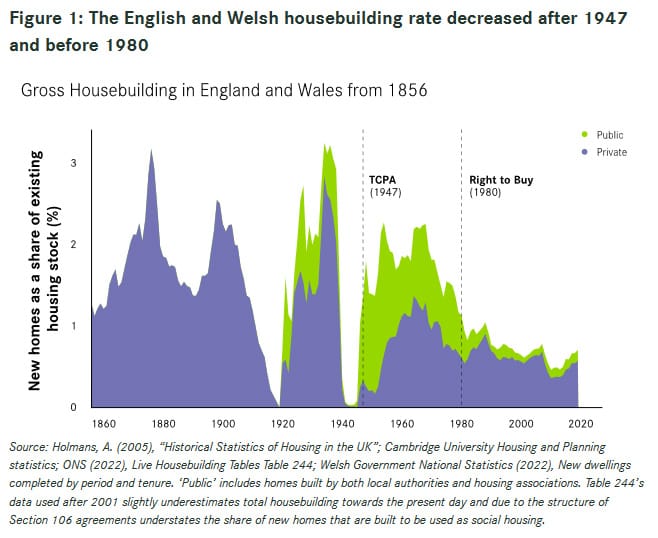

A lot of the problems in Britain today stem from the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, which empowered local communities to restrict development while also dulling their incentive to approve projects by preventing them from receiving much of the resulting increase in local taxes, with predictable results:

“England and Wales saw housebuilding rates drop by a third after the introduction of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, from 1.9 per cent growth per year between 1856 and 1939 to 1.2 per cent between 1947 and 2019. Private housebuilding fell by more than half over the same period.”

At first, exemptions for designated “New Towns” and an increase in public housing construction courtesy of Minister for Housing Harold Macmillan’s explicit promise to build 300,000 homes a year helped to offset the effects of the Act. But when that policy faded and the exemptions were exhausted, so too did housing construction:

Thankfully, that was a bullet that Australia managed to dodge:

“Early 20th century Australian planning legislation drew heavily on UK planning law, particularly the Town and Country Planning Act 1932. There was strong reliance on a land use zoning system by which particular uses or developments might be ‘permitted absolutely, permitted with consent, or totally prohibited’. While the UK shifted away from land use zoning in 1947, introducing the discretionary system and nationalised development rights, no such fundamental shift followed in Australia. Subsequent iterations of Australian planning legislation have introduced discretionary criteria for assessing the social, economic and environmental impacts of development. However, new laws have tended to overlay, rather than overturn, existing planning schemes and implied development entitlements fixed by zoning.”

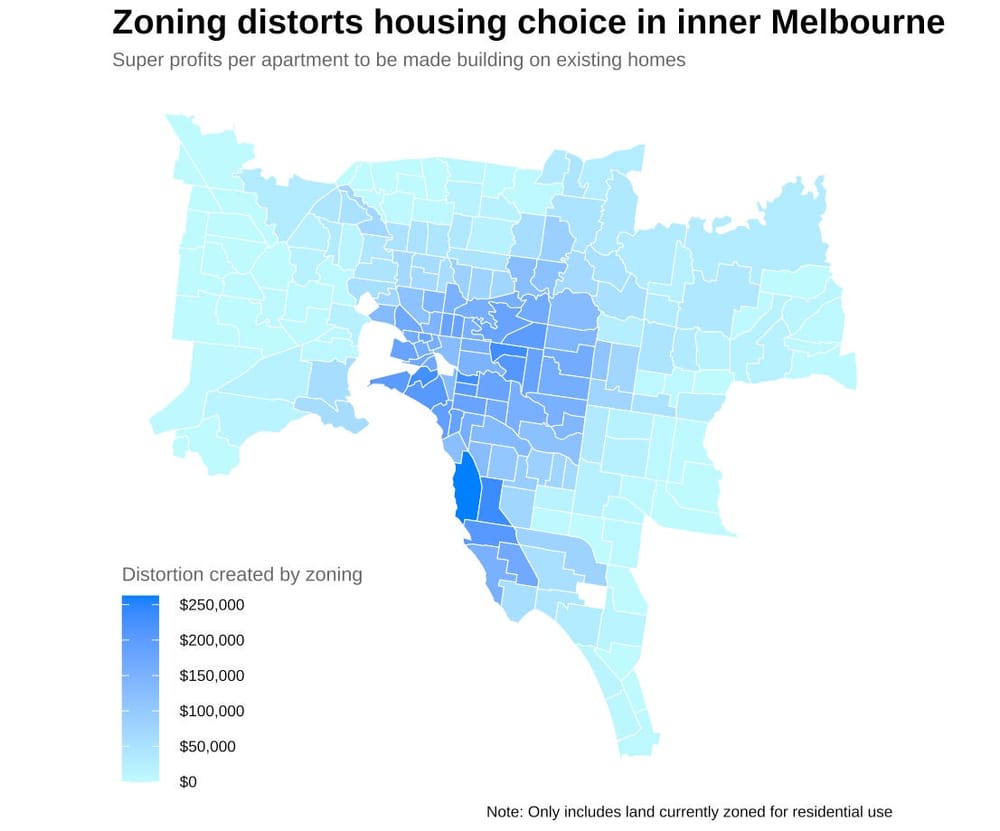

That’s not to say Australia’s mix of national housing policy and State/local urban planning and regulation of private sector development is anything close to optimal. It might be better than Britain’s, but is still lacking, with zoning driving up land prices in well-located areas:

“We’ve calculated the distortions created by zoning for inner and middle Melbourne and the situation is dire. Zoning in areas like Boroondara is distorting the value of land, to the detriment of people who want to live in apartments.

Planners should quantify the costs of restrictive zoning regularly and publish their findings. Measures of distortion created by zoning in each local area should be a metric that keeps planners up at night. This figure should be calculated for each neighbourhood every quarter, and when the number grows and yet planning applications do not then the warning lights should flash red.”

Here’s the impact:

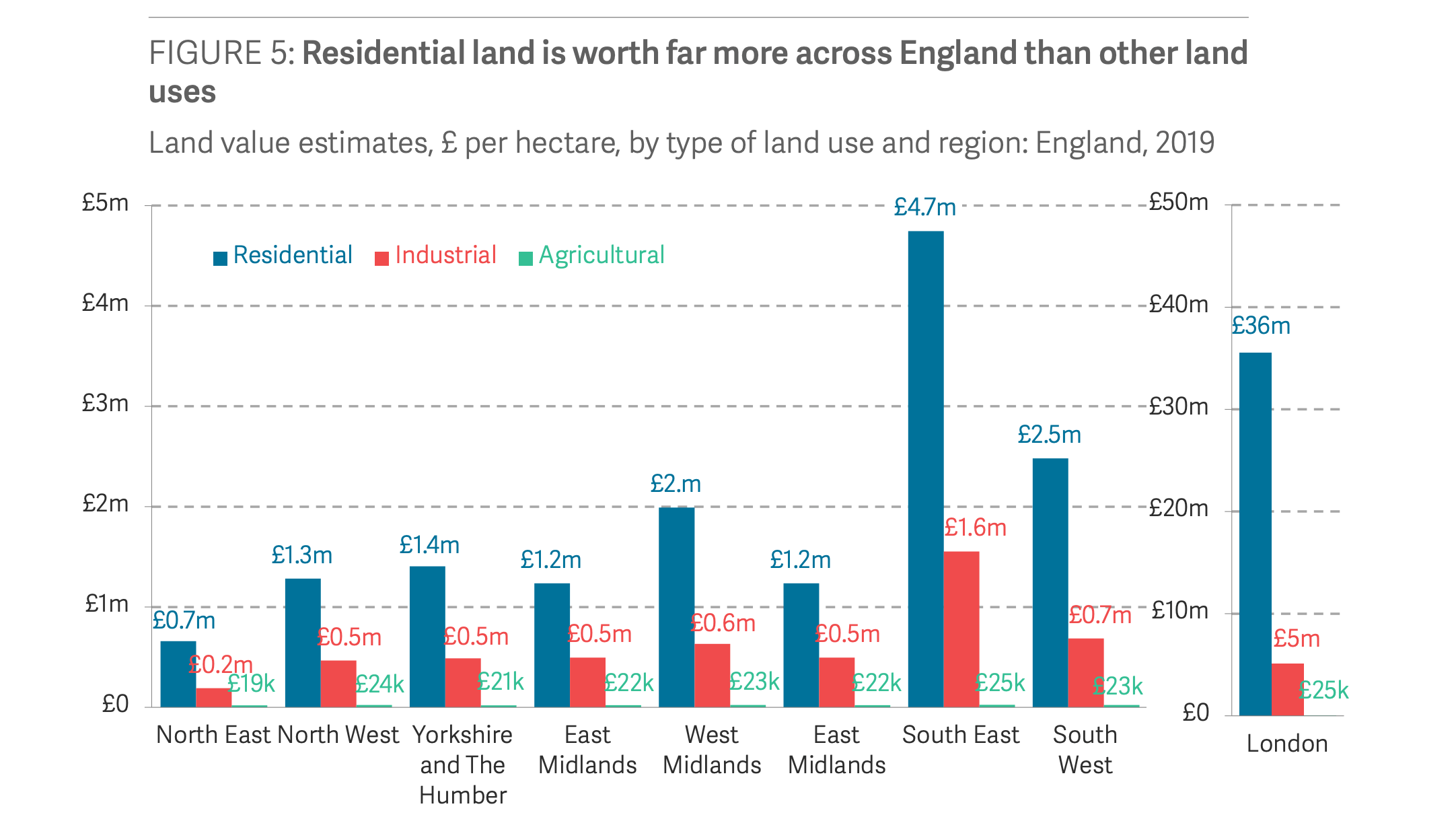

The Resolution Foundation mapped the impact of land use restrictions in England by comparing prices for residential-zoned land to adjacent farm or industrial land, with the difference a proxy for the cost of zoning:

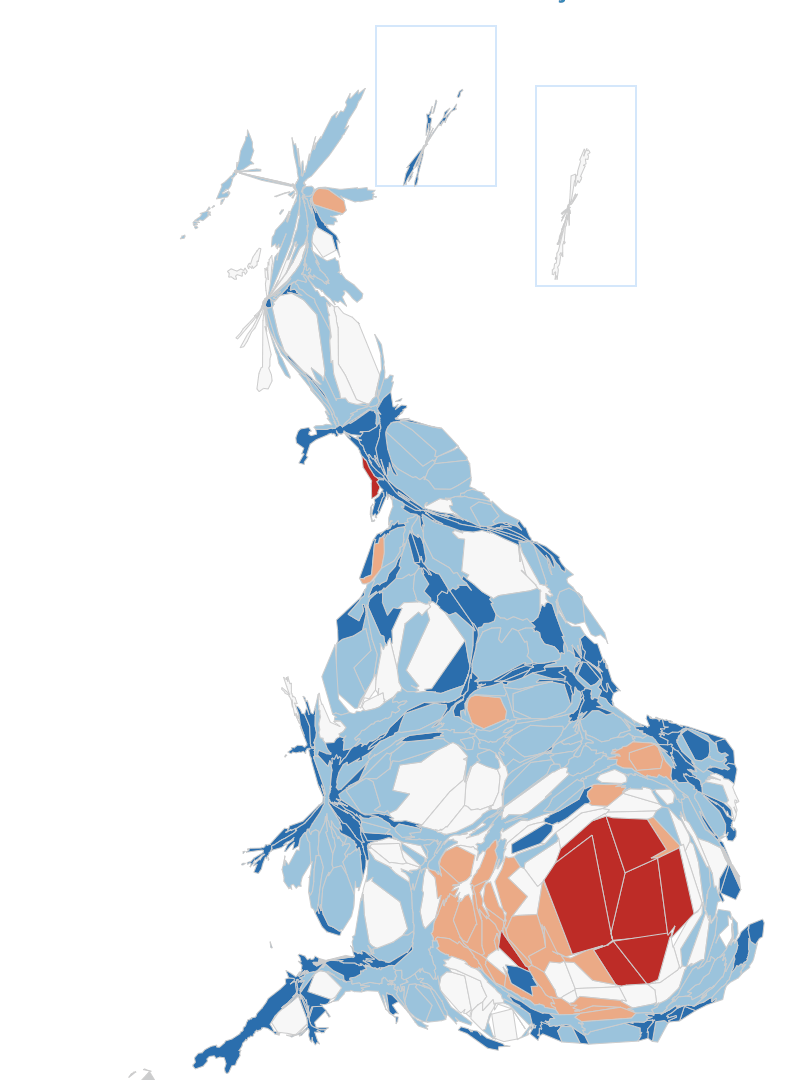

We might have got there via a different institutional path to Britain, but the effect is the same: it drives up the cost of housing to the point that it stops people from moving to where they can be more productive. In the UK that’s the South-East, where an average job in the “dark red areas pays double as much as the average job in dark blue areas” (although even that engine of growth is slipping):

In Australia it’s our capital cities, yet the people close to the peak of their career productivity are increasingly fleeing, and housing costs are likely the culprit: there’s " a strong negative correlation between the ratio of house prices and the direction of people flows for 30- to 39-year-olds", with potentially high future costs:

“Young people will continue to leave Sydney, lest they come from significant familial wealth. This demographic shift has future ramifications beyond people being unable to see the grandkids as often. Cities are important breeding grounds for career development, and younger generations may permanently miss these key formative experiences. At the same time, they also bring an inimitable level of dynamism to a city’s economy. Young people are more likely to work in innovative start-ups and provide the backbone of many essential services.”

In other words, if we don’t sort out our housing issues then it may not be long before we join Britain in economic stagnation.

Britain can’t build

But it’s not just houses. Compared to France – a highly taxed, heavily unionised country where “strikes are so common that French unions have designed special barbecues that fit in tram tracks so they can grill sausages while they march” – the UK is still relatively unproductive, and “France’s GDP per capita is only about the same as the UK’s because French workers take more time off on holiday and work shorter hours”.

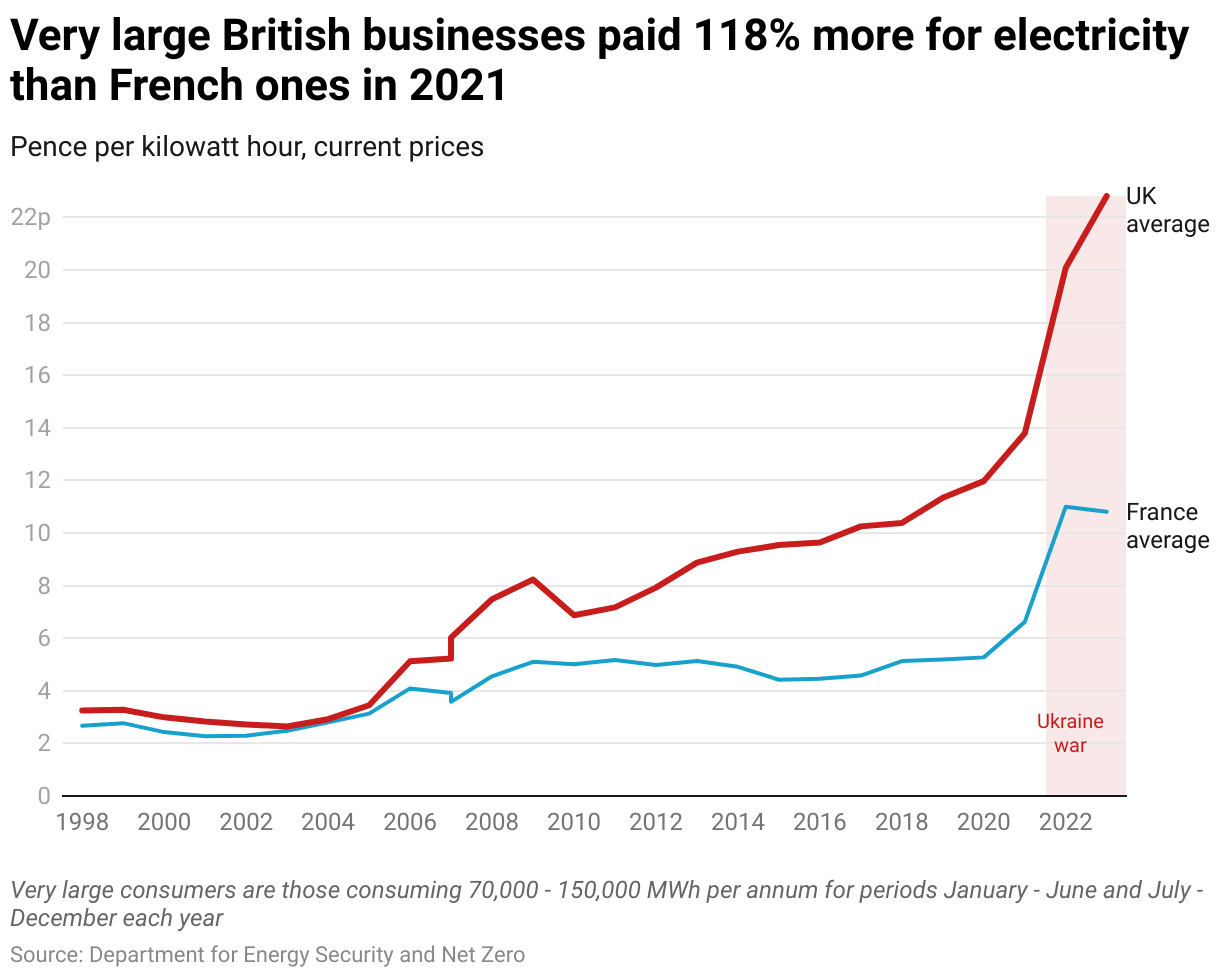

The key advantage France has over the UK is it can build. Housing supply is relatively unregulated, post-War Paris has continued to grow much faster than London, its major cities have excellent transport infrastructure (I was there last year and it’s better than Germany these days), and energy – 70% of which is from nuclear – is more abundant and reliable:

That gives France flexibility:

“Because France gets these big things right, it can afford to get a lot of other things wrong. If Britain could catch up with France on housing, infrastructure and energy, without making the sort of mistakes it makes on regulation and tax, the implication is that we could be far richer than they are, as we were for centuries before the 1950s.”

Today, per capita electricity generation in the UK is just two thirds of what it is in France. It’s trying to build more nuclear power plants, but at a cost four times greater per megawatt than the Czechian government is paying South Korea’s KEPCO to build.

How did Britain get itself into such a bind? Distortions in the tax code that penalise capital investments, higher input costs (energy) that make it less competitive destination for capital investment, and because “the state bans the very investments that would be most valuable”.

When building isn’t outright illegal, the regulatory burden can be prohibitive: the application process to build a tunnel connecting Kent and Essex cost $A580 million, and runs 360,000 pages long. Reopening just five kilometres of track for the Bristol-Portishead rail link took 18,000 pages at a cost of $A60 million.

It’s never too late

The UK is further along the road to expensive, poor-quality housing and inadequate infrastructure than is Australia. Notwithstanding recent efforts to destabilise Australia’s reputation as a place where capital is safe from regime uncertainty, and an energy transition that looks shakier by the day, our major structural problem relates to housing.

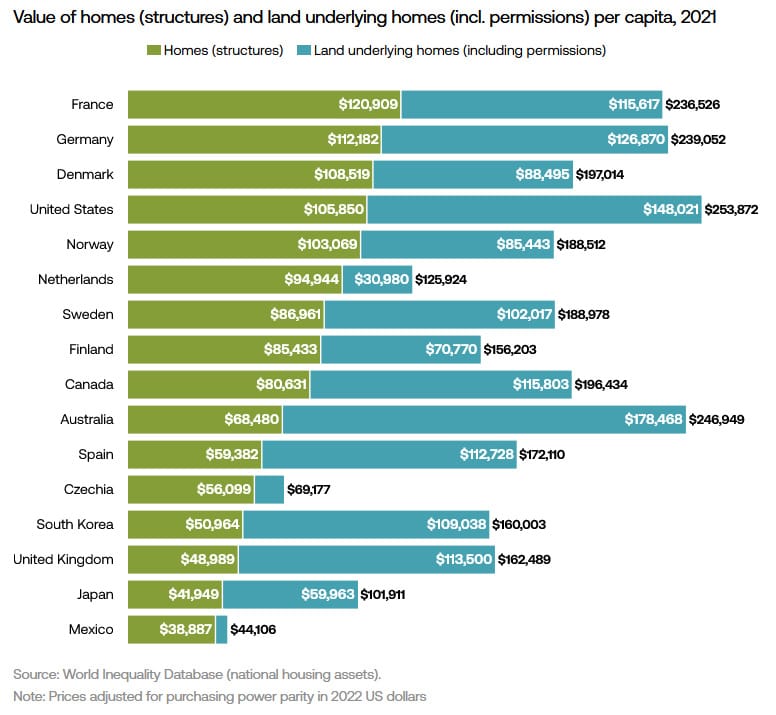

In fact, we have the world’s largest measured gap between the structural value of our homes and the value of the land on which they’re built, implying a significant regulatory premium:

We choose to have expensive housing, and that’s an awful lot of potential social and economic value that we’re leaving on the footpath. As economist Saul Eslake said last week, our problems – like many of the UK’s – stem from “60 years of bad policies”. The first thing politicians should do to fix it “is stop doing dumb things”:

“Stop needlessly inflating demand by scrapping all the programs that needlessly inflate demand, and stop constraining supply by stop doing the things that constrain supply.”

Given the mountain of evidence about how programs that inflate demand and restrict supply reduce housing affordability, surely our governments have at least stopped doing that, right? Unfortunately, no – this was tweeted yesterday:

If we can’t stop doing dumb things like stimulating demand into a market with inelastic supply, what hope do we have for politicians to do the much harder job of structural reform?

It certainly won’t be easy; the political incentives run in the opposite direction to housing affordability. To paraphrase former Prime Minister John Howard, he never met anyone who complained about their house price going up, and nearly 70% of Australian households own their home – and they all vote. Zoning reform works, but the benefits take several years to materialise against a political cycle that runs for, at most, three to four years.

The report on the UK I cited earlier recommended that [emphasis in original]:

“Britain’s best chance of achieving rapid economic growth in the near term is via a combination of higher private investment, more agglomeration – that is, greater clustering of economic activity in productive places – and lower energy costs.

These economic foundations are important determinants of how productive workers and businesses are.”

Like in the UK, Australians still respect the rule of law, reward entrepreneurship and tolerate freedom of expression (although we’re rapidly losing that). Those are much more difficult to develop than sensible transport, energy and housing policy, which require nothing more than to “remove the barriers that stop the private sector from doing what it already wants to do: build homes, bridges, tunnels, roads, trams, railways, nuclear power plants, grid connections, prisons, aqueducts, reservoirs, and more”.

It sounds simple but my worry is: what incentives are there for politicians to risk their careers on structural reform, other than when the economic situation gets so dire that they literally cannot afford to just stimulate demand anymore? I mean, even with a woefully poor economy by global standards, Britain’s politicians still refuse to engage on the reforms needed to right their economic ship. Australia isn’t quite as bad (yet) and our public debt to GDP is about half that of the UK’s, so kicking the can down the road for another few political cycles is probably still the path of least resistance.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!