Making Australia Great Again

The title of this post is a play on MAGA – Make America Great Again – which is basically a blanket term for former President Trump’s protectionist policies. Those policies are founded on the belief that the loss of manufacturing jobs in America was a deliberate choice, rather than the natural outcome of an evolving economy. Many of those policies have been broadened by the Biden administration, and if Trump wins a second term he’ll almost certainly double-down on them.

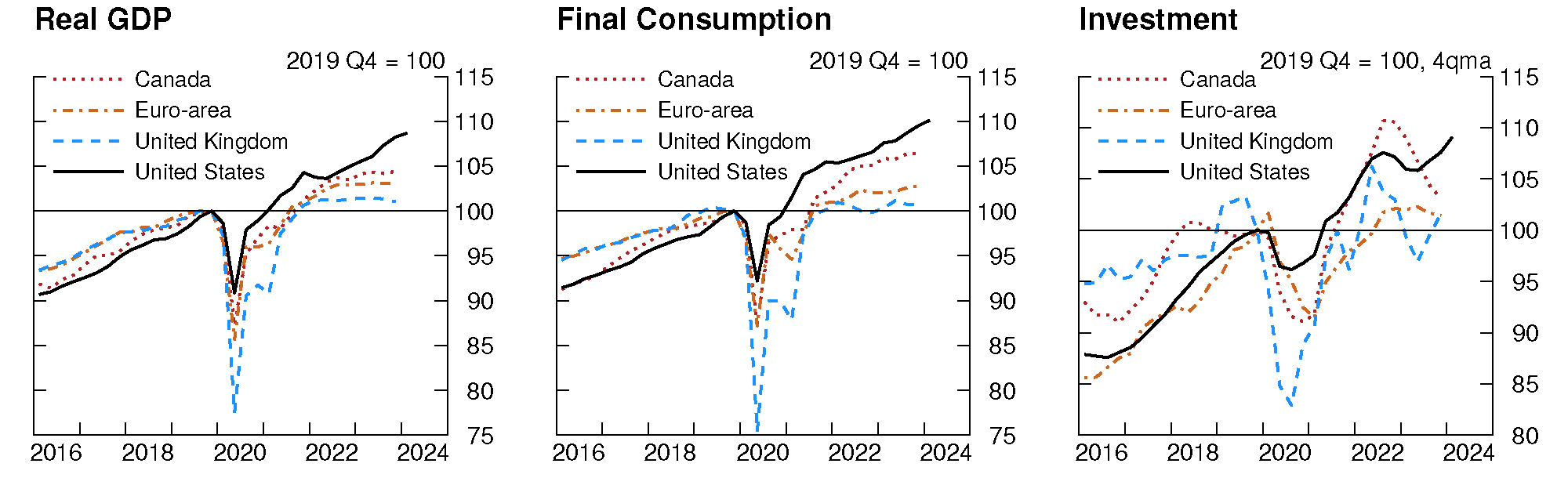

But America never lost its greatness. It’s still the world’s largest economy, is the wealthiest country after various oil-rich states, entrepots and corporate tax havens, is the second-largest manufacturing nation in the world by output, has the largest military spending by a long way, and has bounced back better than most from the pandemic:

That’s not to say that America doesn’t have its share of problems; just that losing manufacturing or its ‘greatness’ isn’t one of them.

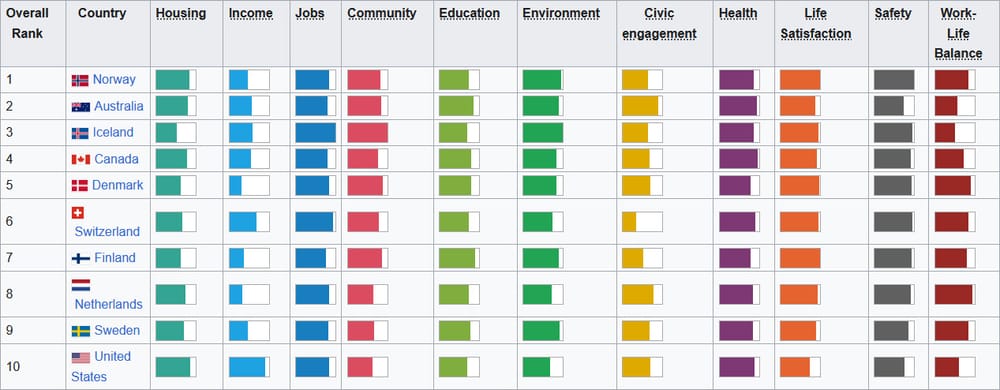

I actually think Australia is still pretty great, too. We rank highly on various global indicators, including first for equity and healthcare outcomes, third for overall healthcare, twelfth in terms of GDP per capita, and fourteenth in the ease of doing business. The OECD’s Better Life Index – which scores various measures of well-being across countries – ranks us second overall (the methodology is still being fine-tuned and currently gives an equal weighting to each measure):

We regularly punch above our weight on the world stage, so much so that the world keeps talking about our 4th overall finish on the Olympic medal tally, despite ranking 55th in population Raygun.

But that hasn’t stopped many Aussies, led by PM Anthony Albanese (Albo), from jumping on the MAGA bandwagon. The loss of Australian manufacturing was such as big blow that they want to impose some variation of Trump- and Biden-style industrial policy down under to ‘restore’ its share of output to an arbitrary point in history. Those policies have been lumped together and tabled to Parliament as the Future Made in Australia Bill 2024, which looks set to be passed in September.

We’ve never had it so good

I’ve written a lot about why a Future Made in Australia is a terrible waste of resources, but a recent article in the ABC about the forthcoming Bill got so much wrong that I thought an update was warranted.

The article begins with a story about the long – but now extinct – tradition of manufacturing in Elizabeth, a suburb in northern Adelaide. It’s a rather thinly disguised attempt to trigger an emotional response in the reader:

“The township was a hub for manufacturing Holden cars and Peter Richardson spent 17 years working on the factory floor.

Back in 2005, Mr Richardson had just bought a new family home for his wife and kids when word spread that lay-offs were looming.

About 1,400 people were expected to be made redundant as the plant looked to cut shifts for workers.

Mr Richardson was left feeling stunned.”

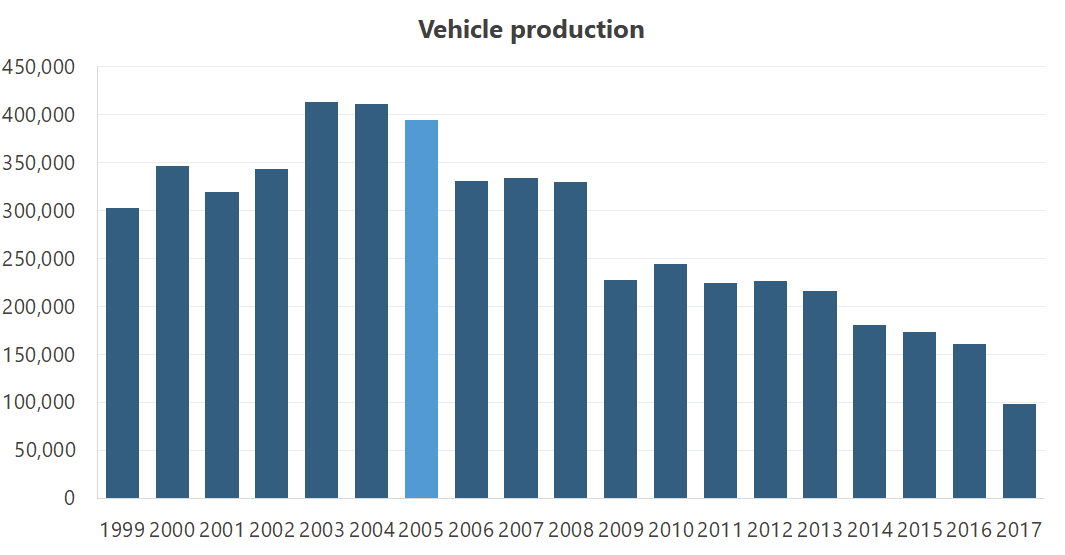

I have no doubt that would have been a shock. Vehicle manufacturing in Australia was peaking in the early-mid 2000s when Richardson was laid off:

But industries fail all the time, and we wasted billions of dollars propping up the auto industry before it eventually collapsed. Indeed, one of the reasons the US has such a successful economy is because of “structural factors, such as labour market flexibility and business dynamism”, that allow it to adapt through sectoral reallocation.

Australia isn’t bad at that, either; Richardson moved from cars to furniture, then to clothing. All eventually shuttered, but presumably he continued to find work, and he wasn’t alone: the University of Adelaide estimated that within a year of Holden closing its doors in 2017, over 80% of its workers had found new jobs.

The thing is, economies change and job losses happen. More than a million Australians change employers every year, or nearly 10% of the workforce. We used to make cars, textiles, electronics, appliances, bicycles, toothbrushes… the list is a long one, yet unemployment today is close to historic lows. It just wasn’t a good use of people’s time to be making those things in Australia.

We’ve also become wealthier, thanks in part to importing such goods from overseas where they can be made with fewer resources. Instead of toiling away in a physically-demanding factory, today around four in five Aussie workers are in the services sector – a luxury afforded only to the wealthiest of nations.

On a wing and a prayer

Moving back to the ABC article, after trying to tug on the reader’s heartstrings the author went on to lament the fact that “manufacturing once represented about 29 per cent of Australia’s GDP”, before introducing Professor Roy Green to say that process was “very short-sighted, very narrow, and counterproductive”:

“Professor Green said the main emphasis was on ‘rebuilding capability’.

‘Extending manufacturing competitiveness into areas where each country feels that they have proficiency, skills base, and ultimately a competitive advantage’, he said.”

A lot of buzzwords in there! Ignoring the fact that it wasn’t a conscious policy decision to move away from manufacturing – we happen to be endowed with an abundance of natural resources that Japan, Korea and China want a lot of, and Aussies love to consume services – Green went on to elaborate:

“He said it was about picking areas of competitive advantage, citing the example of South Korea which developed a strategy in the 1960s and was now among the leading manufacturers.

‘It was told by the World Bank, if you work hard at it, you might become self-sufficient in rice production. That was the message they were given by the sort of market-based economists’, he said.

He explained South Korea decided it wanted to become a manufacturing nation.

‘So they started in a small way, with import substitution, making their own cars and so on. Now, they’re in large areas of manufacturing… and they did it themselves’, he said.”

The World Bank, that bastion of “market-based economists” (I jest), never told South Korea it couldn’t become successful at manufacturing, and it certainly never said “you might become self-sufficient in rice production”.

The Bank has been working with South Korea since 1955, and was fully on board with the government’s desire to progress from an agrarian society into a manufacturing hub. It directly assisted South Korea’s government in improving its state capacity, and offered “a combination of financial and technical assistance in four sectors (agriculture, transportation, finance, and education)” – mostly loans and grants for large infrastructure projects such as railways.

Yes, the Bank was against Korea’s foray into car manufacturing, but its ’experts’ have got a lot of things wrong over the years (doesn’t that also show the folly of trying to pick winners – you can easily miss them?).

According to Columbia University’s Arvind Panagariya, if anything industrial policy and targeting slowed South Korea’s development:

“Let’s look at that: 1963 to 1973—full decade—Korea grew 9.1%. This is, of course, the beginning of the miracle. Was that beginning of the miracle in any way connected to this industrial targeting? No, in fact, this is a period during where there is no industrial targeting. Policies are all neutral, entrepreneurs are left to themselves to decide what they want to export.”

When the South Korean government started industrial policy in the 1970s, it picked winners and plenty of losers. Would the winners have won anyway? We can’t know. But we do know that growth slowed until the policy was abandoned in the 1980s and the government returned “to liberalisation and neutral policies, no targeting”, which saw growth pick up again.

In his recent book Free Trade and Prosperity, Panagariya looked at other countries and found that it was only when they removed their protections – e.g. the import substitution policies Green is suggesting – that they started to truly develop:

“A common argument made by critics is that if we take a snapshot of a rapidly growing economy such as Taiwan in the 1960s or China in the 1980s, we would observe continuing high levels of protection. This raises the question of why protection rather than liberalisation might not be the source of the rapid growth. The answer to this misleading critique has two parts. First, in both cases, liberalisation preceded or accompanied growth acceleration. If the countries still looked highly protected, it is because they began too far away from the free trade position and too close to autarky. Second, if protection was indeed the source of rapid growth in these cases, its reduction during the following years should have led to a decline in the growth rate. But the opposite was observed when Taiwan in the 1970s and China in the 1990s and 2000s opened their economies further.”

Professor Green – who apparently advises state and federal governments – wants Australia to move in the other direction; for the government to forcefully expand manufacturing’s share of GDP, target specific industries, all to “get much greater complexity and resilience. That’s the reason for [a] Future Made in Australia”.

But you don’t need to make stuff in Australia to improve complexity and resilience: both France and the USA have larger services sectors than Australia but are much more economically complex, yet their manufacturing sectors are only about double ours.

Could we double our manufacturing share of economic output? Sure; the government can certainly increase the production of certain goods by more than would occur in a freer market. But there’s an opportunity cost of doing so, and in Australia a good amount of our low economic complexity and manufacturing share is due to the huge commodity sector that bids labour and capital away from its next-best uses, including manufacturing. Any diversion of resources away from that sector – Australia’s most productive – will lead to a potentially significant reduction in wealth.

Australia should sit this one out

When announcing a Future Made in Australia, Albo was quick to invoke the argumentum ad populum fallacy:

“All these countries are investing in their industrial base, their manufacturing capability and their economic sovereignty. And – critically – none of this is merely being left to market forces or trusted to the invisible hand,” Mr Albanese said in April.

“It is being facilitated, enabled and empowered by national governments from every point on the political spectrum. Because this is not about ideology, it’s about opportunity – and urgency… Australia can’t afford to sit on the sidelines”.

To the contrary, we can’t afford to play a game that is effectively a race to the bottom. If we truly want to keep Australia great and improve our “economic sovereignty”, start with fixing housing policy. Remove all restrictions on energy extraction, and legalise nuclear power. Cut red and green tape, helping renewables compete with coal and reduce the need for perpetual subsidies.

Most of all, stop racking up public debt and start banking some of the commodity windfalls so that if something bad were to happen, we’d have the fiscal capacity to do something about it. Is that not resilience?

The fact is no country becomes (or stays) successful through import substitution policies, which is what our government is attempting with a Future Made in Australia. They become Argentina. When the Bill was read to Parliament, Senator Helen Polley said the quiet part out loud:

“We can be self-sustaining with everything we need, and we can make it right here in Australia. Australia has leading industries, world-class resources and the smartest workers on the planet.

Put simply, A Future Made in Australia is about seizing the opportunities of the move to renewable energy while becoming a country that makes more things in its own backyard… We can no longer rely on the rest of the world for the products that we need when we have the capacity to make them right here.”

But why? Just because you have the capacity to make something doesn’t mean you should make it. Nations get and stay prosperous only after unwinding such policies, building productive infrastructure, ensuring there’s a competitive marketplace, supporting robust education and health systems, and then getting out of the way!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!