Migrants aren't causing inflation

Perhaps it’s because the recent bout of inflation was so unusual – other than failed nation states such as Argentina, Zimbabwe, or Venezuela, it had been over thirty years since most countries had to worry about it – but people really like to blame anything and everything for it except the actual causes.

For example, earlier this year former chair of the ACCC, Allan Fels, pointed the finger at so-called ‘greedflation’:

“No one looks at the role of prices, price setting, profit margins in relation to inflation, and in relation to what could be done about high prices. The actual setting of prices by business has added quite a lot to inflation. And that’s often disregarded. Other things are blamed, monetary policy, war, etc. Business prices contribute a lot to inflation.”

Greedflation – the idea that businesses jacked up prices, leading to inflation – is also supported by think tanks such as the Australia Institute, which this week called it “profit-driven inflation”:

“In this day and age we’ve got profit-driven inflation, we’ve got supply shocks from things like Covid, the war in Ukraine, and we’ve also increasingly got climate shocks affecting things like the insurance industry very significantly.”

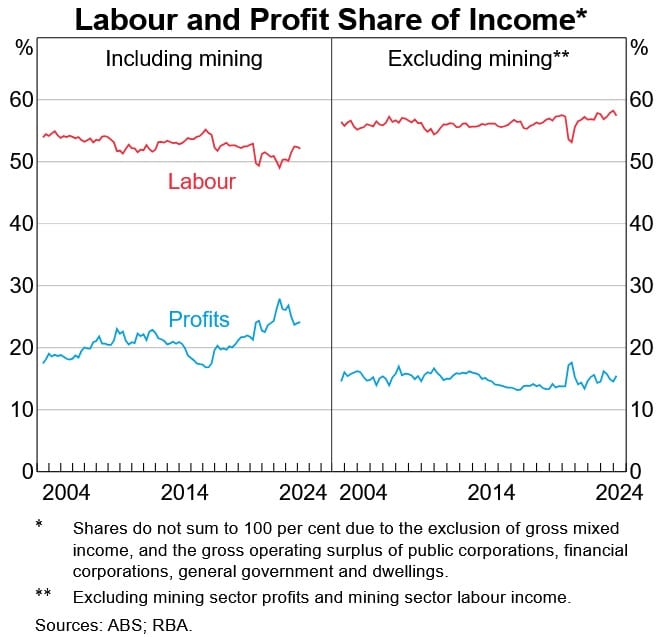

But firms are always greedy. If businesses could have jacked up prices in 2019, they would have. Did something change in 2020 to suddenly cause an outbreak of greed that also gave firms monopoly power over prices, including our commodity exporters who sell globally (i.e. are largely price-takers)? Only for that greed to rapidly subside, with the non-mining profit share of income now back to around its long-run average?

Where there is some truth is in the supply shock inflation story. Recently attention has moved to migration, specifically its impact on housing demand and the rental crisis. But some have taken it even further, claiming that migrants have “driven” the recent inflation, as alluded to in tweets like these:

Even Treasurer Jim Chalmers claimed that by “managing” the population (i.e. reducing the migrant intake), he would moderate inflation:

“We’re seeing a substantial moderation in inflation in the forecasts and in the last couple of years as well, and that is largely because of how we’re managing the budget, but it will also be increasingly about how we’re managing the population as well.”

Or there was this in a popular Murdoch rag last November:

“This surge in population, combined with the tight rental market, has combined to push Australia’s rental inflation through the roof, which is also driving up overall CPI inflation.”

To be clear, supply shocks cannot increase inflation beyond the short-run. They can temporarily increase measured inflation because of how the CPI basket is designed. But all a supply shock really does is alter relative prices in the economy. If climate change raises insurance costs, the price of insurance increases relative to all other prices in the economy. If migrants increase the demand for housing, the relative price of housing increases.

Inflation is an increase in the general level of prices. Price rises in housing and rentals incorporate both inflation and their relative price changes. There is no “rental inflation”, only a change in the relative price of housing and inflation. As the US Fed makes clear in its explainer, terms like “housing inflation” don’t exist:

“Inflation cannot be measured by an increase in the cost of one product or service, or even several products or services. Rather, inflation is a general increase in the overall price level of the goods and services in the economy.”

The only way for all prices to rise is if money growth outstrips the demand for money. So, while supply shocks can alter relative prices and measured inflation in the short-run, they cannot “drive” persistent inflation. That includes migrants, who tend to be disinflationary.

What actually causes inflation

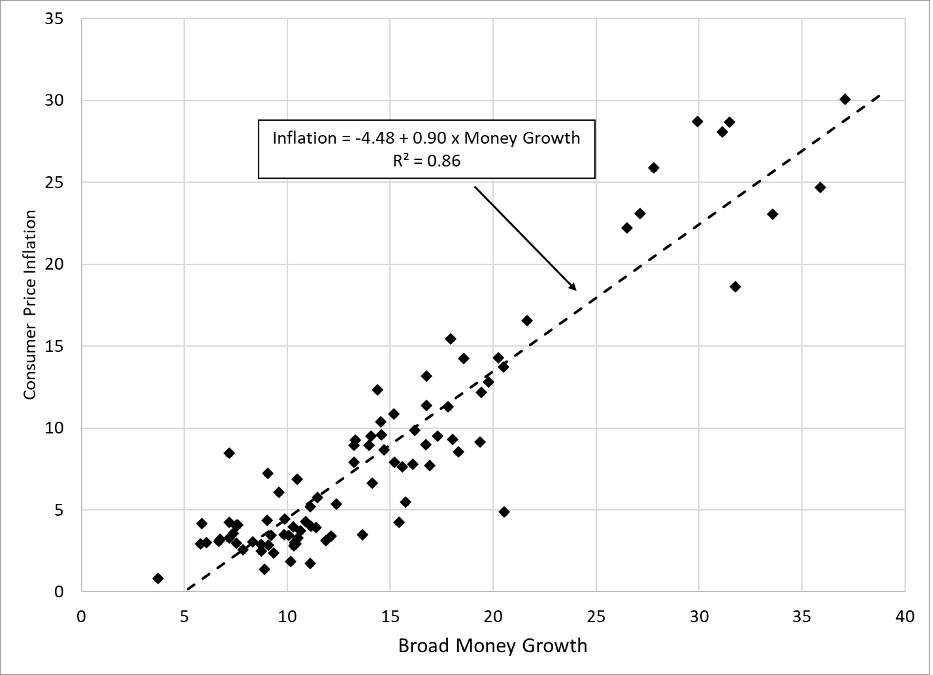

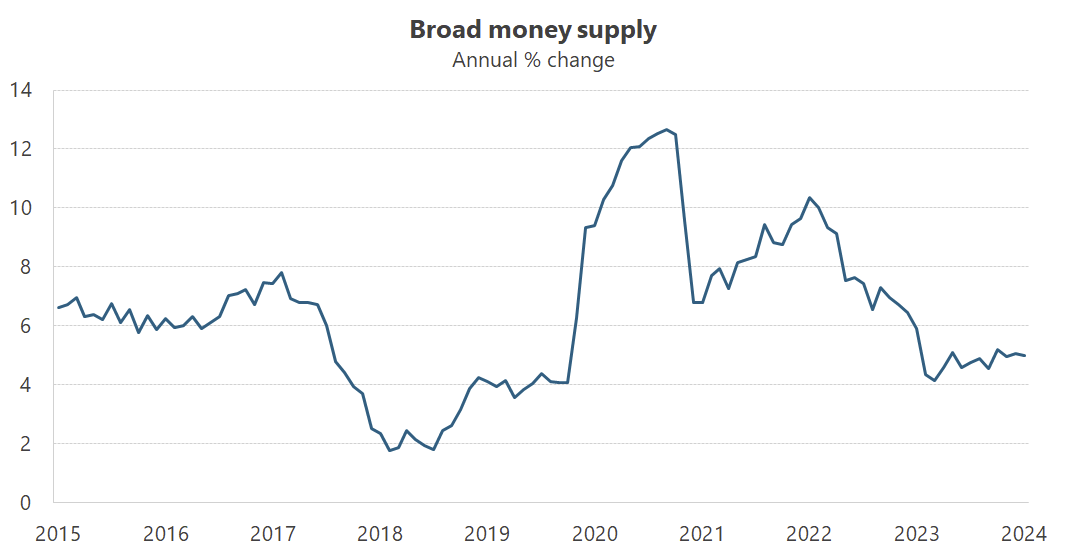

Inflation is caused by fiscal and monetary policy. In times of high inflation it’s strongly correlated with the money supply, both historically and during the recent surge:

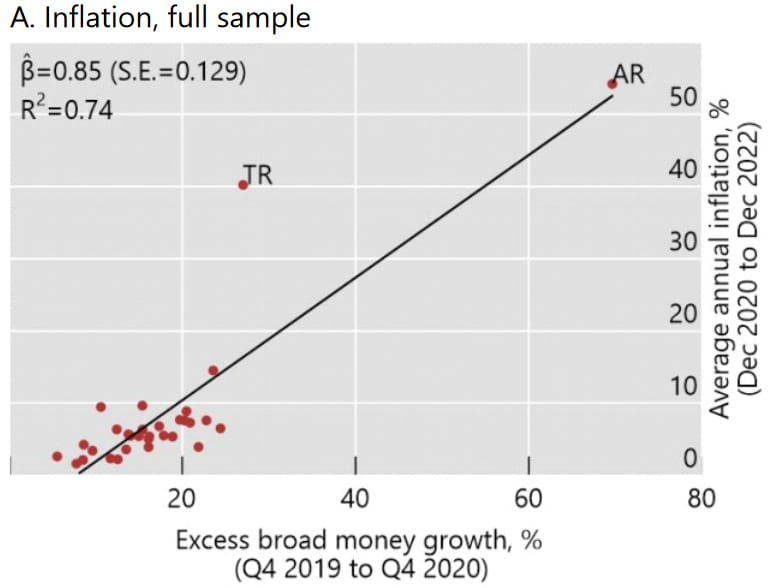

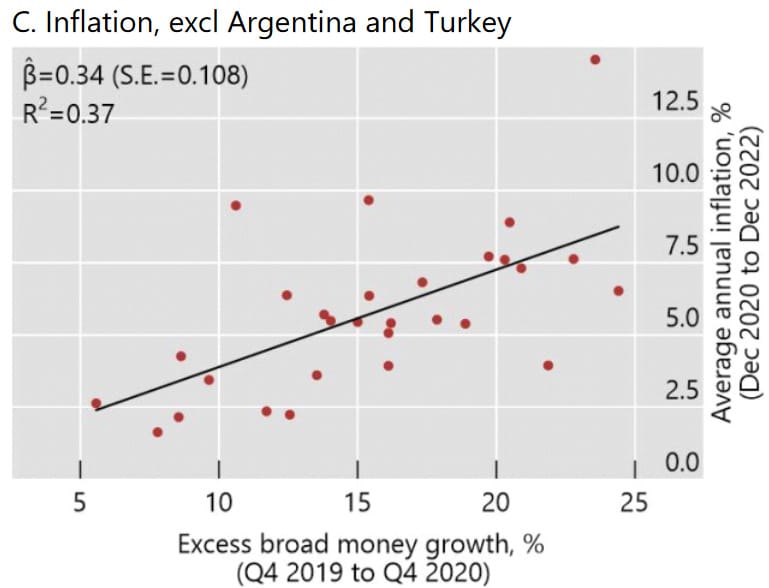

According to the Bank for International Settlements, during the pandemic money growth was predictive of each nation’s subsequent inflation:

“Across countries, the underprediction of inflation was greater for those countries that saw higher excess money growth during the pandemic. Each 1 percentage point difference in the rate of excess money growth in 2020 across countries reduces the average 2021–22 inflation forecast error by 0.25 percentage points in the full sample (panel B) and by 0.15 percentage points when the two high-inflation countries are excluded (panel D).”

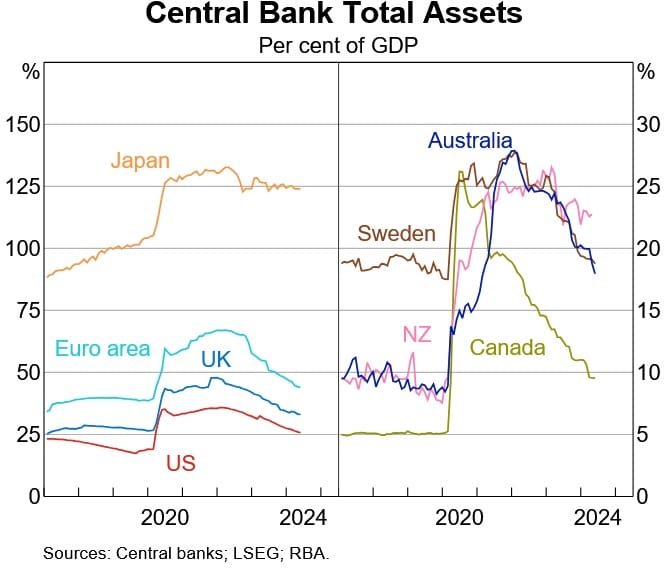

A quick look at the balance sheets of global central banks confirms that they monetised a good portion of their respective government’s pandemic fiscal spending. The RBA did exactly the same, so it’s no surprise that we experienced close to double-digit inflation down under:

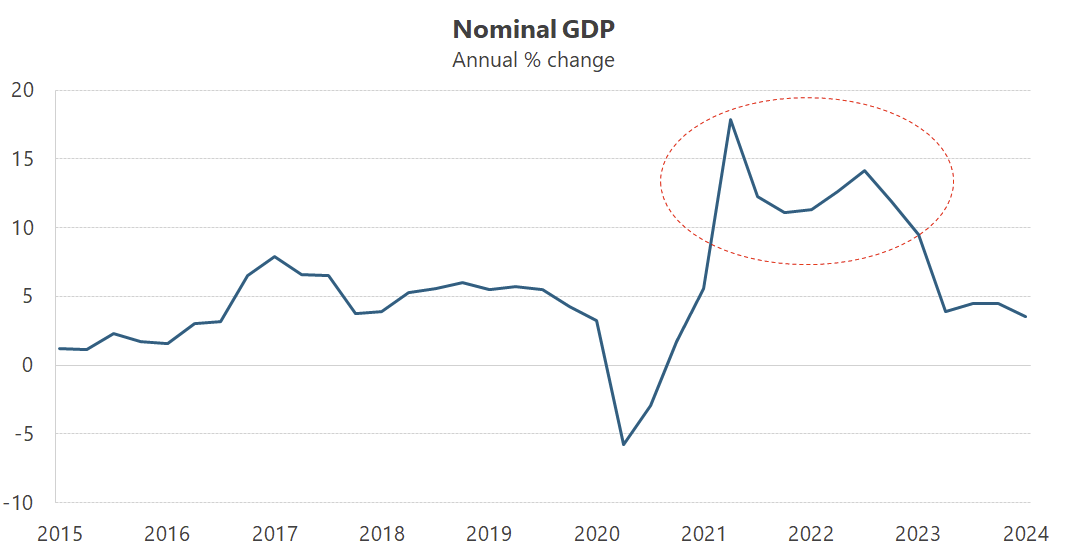

Basically, central banks created more money than people demanded for their transactions. More dollars were then chasing the same amount of goods, i.e. an aggregate demand surge that kicked off when the world’s economies opened back up and people could spend again, which is clearly visible in Australia’s nominal GDP (red circle):

But that money-induced inflation is temporary; growth in both nominal GDP and the money supply have slowed to around 5% annually, which in Australia should be consistent with moderate inflation:

There are lags in how the CPI is calculated (especially with housing), but as I wrote the other week, the RBA has (belatedly) done its job. Any above-target inflation from here is probably going to come not from money growth but government policy (e.g. wages, debt-financed handouts) and demographics.

The rise of Boomerflation

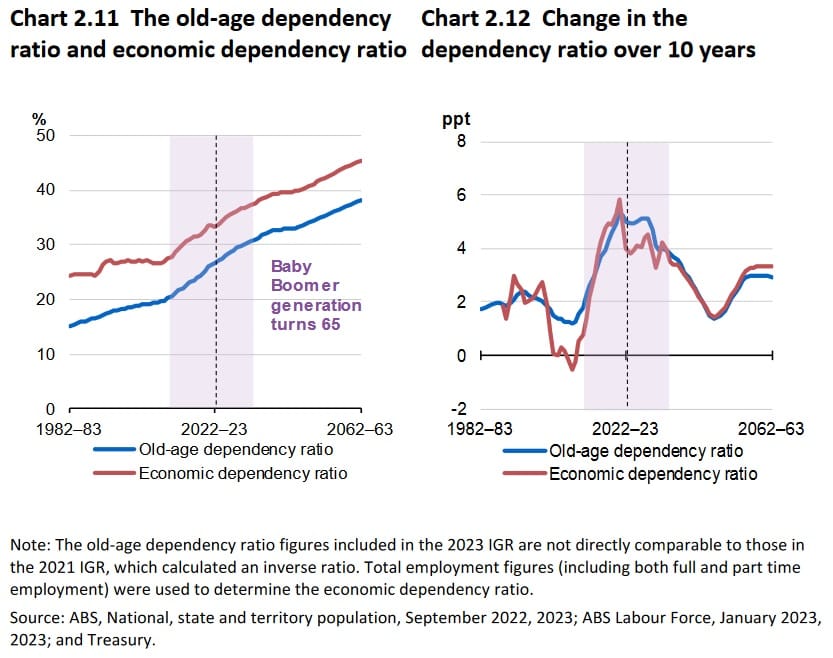

On that latter point, we have a huge cohort of Boomers currently in the process of retiring, with last year’s intergenerational report showing that “the baby boomer cohort started to reach the age of 65 in the early 2010s”.

A rising old-age dependency ratio can raise inflation if the RBA doesn’t properly offset it, which (as I’ll discuss in a bit) it may not. A study by the IMF “found a strong link between trend inflation—the average rate at which prices increase over a several-year period—and the age structure of the population”:

“Specifically, we found that the larger the proportion of young and old in the total population, the higher inflation. Put another way, when the working-age population is larger, the effect is disinflationary. This link between age and inflation holds for a large number of countries across all time periods.”

Why wouldn’t the RBA offset such changes? The IMF speculates that central banks might not tighten in the face of demographic-related inflation because of “political pressure… to cater to the inflation preferences of dominant age groups”, or a failure “to anticipate movements in the equilibrium real interest rate”.

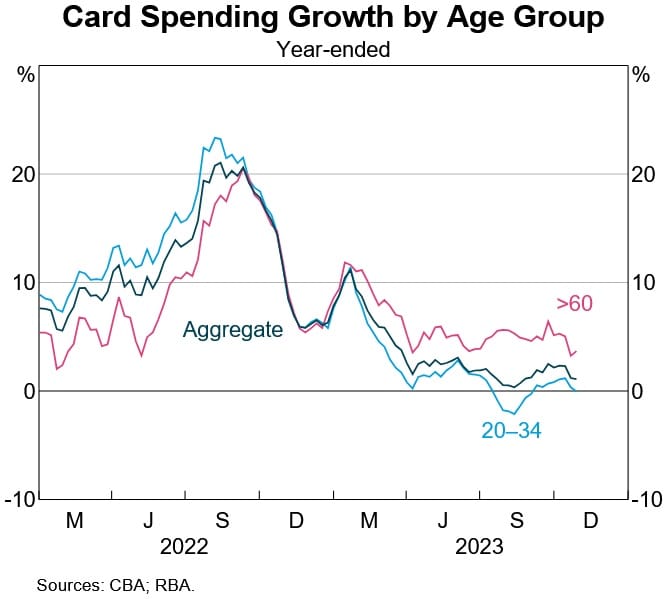

So what are Boomers up to in Australia? According to CBA/RBA research, their spending has been more resilient than those in the younger cohorts (although the opposite was true in 2022), perhaps due to:

“[R]etirees whose income growth has been relatively solid, in part owing to the indexation of government transfers such as the age pension… An additional explanation for the relatively slower fall in spending growth by retirees recently is that they have been slower than younger households to resume consumption of discretionary services (e.g. dining out or attending large events) following the removal of social restrictions.”

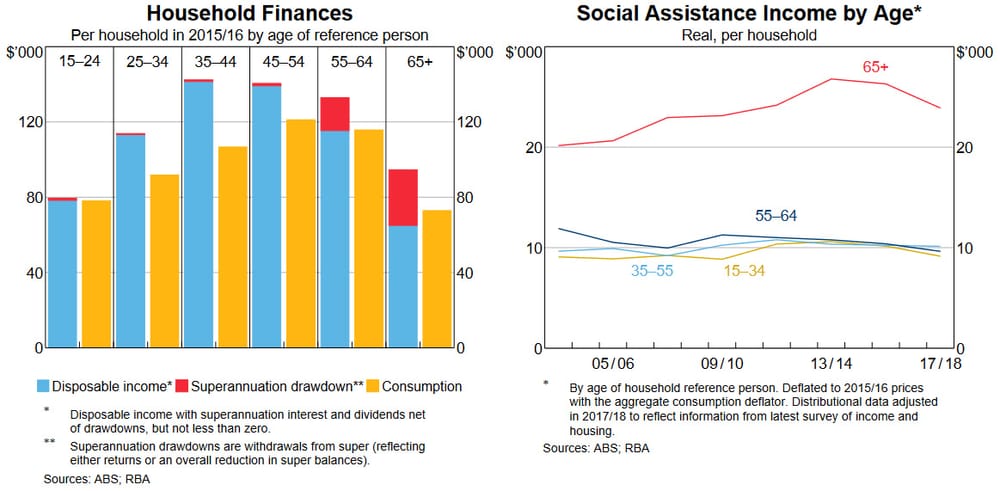

Since 2000, older Australian households have seen their consumption spending grow “nearly twice as fast as the average of other households”, supported by:

- Growth in real pension payments “in excess of both the consumer price index and the wage price index since 2003”.

- Children staying at home for longer (increasing household size).

- The drawdown of superannuation.

- Higher financial incomes, with older households benefiting the most “because they hold more financial wealth, on average”.

Retired Boomers still spend, on average, less than other households. But that spending is more likely to be inflationary because their consumption is greater than their labour income (i.e. output), and much of their income comes from debt-financed government transfers.

Again, the RBA can offset these potentially inflationary impacts, but it may not want to – perhaps more-so now that the Treasury Secretary is on its board.

Migrants help to keep inflation down

According to the RBA, it’s the “increase in young overseas migrants over the past decade… [that] has made Australia relatively well placed, compared with many other advanced economies, to adjust to the effects of an ageing population”.

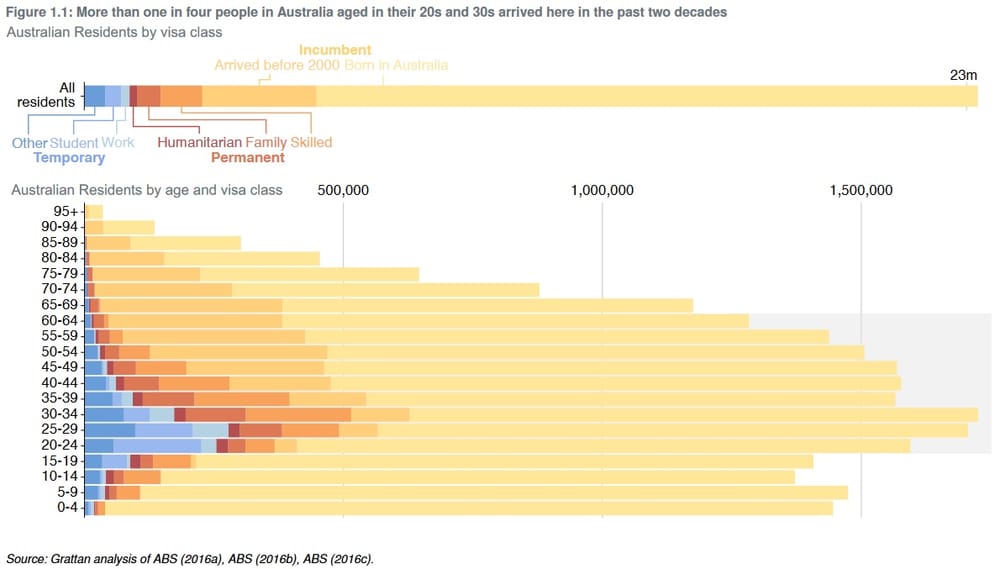

Migrants to Australia tend to be young and, at least in the permanent stream, well-educated:

“In 2021–22, 76 per cent of new migrants were aged between 15 to 34. This compared to 27 per cent of the incumbent population… the majority (79 per cent) held a Bachelor degree or higher, with another 13 per cent holding an Advanced Diploma or Diploma level qualification.”

Temporary migrants are forever young because most only hang around for a few years; they’re always going to increase our working aged population. Permanent migrants temporarily ease population ageing but don’t resolve it, given that they will also age. But they’re also more likely to work full-time than the Australian-born population, and given their average age on arrival, can certainly help to ease Boomerflation in the medium-term.

This cool chart from the Grattan Institute shows just how important migrants are for fleshing out our working-age cohort, ensuring our demographics aren’t too ’top heavy':

Australia is in the fortunate position of having our pick of the world’s best and brightest migrants. If we maintain those standards, future migrants will continue to be young, educated and employable on arrival, reducing inflation because they raise output. With more output, a given amount of money chases more goods and services, putting downward pressure on prices and offsetting Boomerflation: the RBA’s job is done for it!

Migrants add to demand too, of course, but the literature suggests it’s not close to how much they add to output. For example, a recent IMF report on Australia found that:

- Migrants do not cause adverse effects on native employment growth, because their output leads to a response in the capital stock (investment), raising the capital-labour ratio (productivity).

- Even large migrant inflows do not lead to “significant inflationary pressures”, although there might be a small decrease in housing affordability at the margin, reflecting “structural supply shortages and is best addressed by boosting supply”.

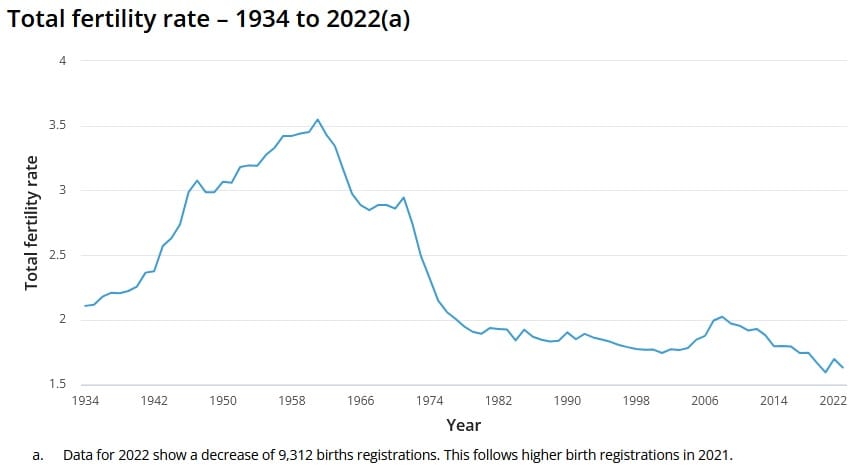

Australia’s fertility rates are flat or falling, making the case for migration even stronger than it has been in the past:

Now, it’s true that migrants create costs as well as benefits. For example, a sudden influx puts pressure on infrastructure, and our governments might be slow to react. So, there could be an argument for region-based migration (i.e. so not everyone goes to Sydney). We already have State-sponsored visas which could relatively easily be increased for regions where migrants are more urgently needed.

Given how important migration is for Australia, there’s also a good argument for easing the restrictions we put on housing construction in well-located suburbs, so that supply can respond to demand and young Australians aren’t priced out of the market.

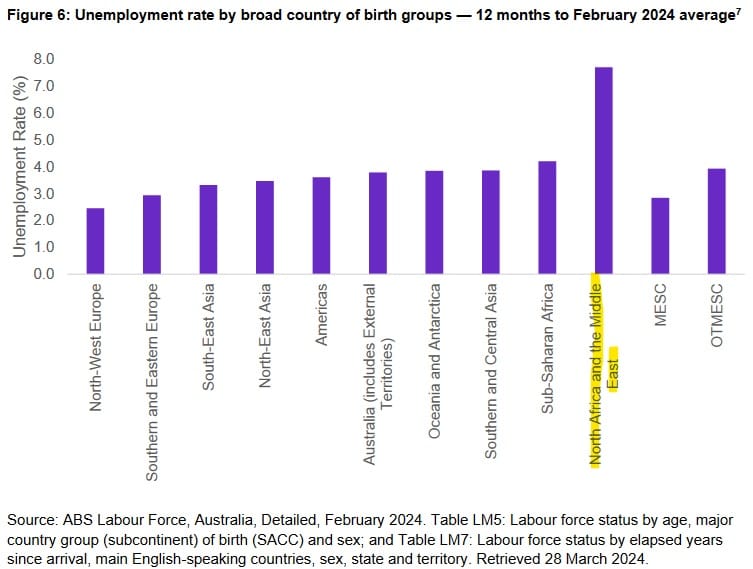

It’s also true that voters have turned on migration, especially in places like Europe. But recent European migration has been dominated by large inflows from Middle Eastern and North African countries, and even in Australia people from those regions have much poorer outcomes than the migrants that Australia traditionally welcomes.

Basically, Australia is different to Europe, and we can continue to welcome migrants to reduce inflation, raise living standards, and help postpone other crises our policymakers haven’t had the will to address, such as our structural fiscal problems.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!