Milei and the nest of rats

Several months ago I wrote about everyone’s favourite eccentric libertarian, Argentina’s President Javier Milei, and the tall challenge that lay ahead of him. Today I thought I’d take another look to see how it’s going, especially given the recent resurgence of neopopulism, price controls and tariffs in the West, which are but three of many forces that have weighed down the Argentine economy for several decades.

But first, a word of caution: economic policy can take a long time to work. Milei has only been in the top job for 11 months of a four-year term and has had to tread cautiously because of the political pressures he faces.

Specifically, Milei needs to navigate the group of people he affectionately describes as a “nest of rats”: Argentina’s congress. Milei’s party holds just 38 of 257 seats in the lower house, and 7 of 72 seats in the senate, so to get anything done he needs to convince not just the former centre-right opposition, the Republican Proposal, but also various independents to support his cause.

Shock therapy

Milei’s biggest achievement came at the end of June, when his heavily watered-down “omnibus” bill (from 600 articles to 238) cleared both houses:

“The sweeping reform push will usher in the privatisation of some state firms, the relaxation of labour laws and a new foreign investment incentive scheme, among other changes.

The raft of reforms – which contains more than 200 articles and comes with an accompanying fiscal package – was enacted after months of debate and violent protests against the bill, amid a punishing recession and harsh austerity measures that have hit Argentines hard.”

The reforms contain several promising elements. For example, if the government fails to respond to a request or application within a specific time frame, it will be automatically approved. As for the investment promotion regime, The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) reckons it:

“[P]rovides generous tax, trade and foreign-exchange benefits for 30 years for projects worth more than US$200m in the forestry, tourism, infrastructure, mining, technology, steel, energy, and oil and gas sectors… [which] will encourage large-scale investments in Argentina’s most competitive sectors.”

However, the EIU cautions that Argentina’s institutions are too unstable – it has a “history of political instability and policy swings” – for it to have as much impact as it could. Milei’s maintenance of Peronist currency and capital controls – a political decision to artificially reduce measured inflation – will also perturb investors, who are likely to “push decisions back as they take a wait-and-see approach”.

Still, the passing of the omnibus bill was the first time Milei had moved anything through congress, having relied exclusively on executive orders up to that point. From what I can gather, other than this bill Milei’s government has:

- reduced the number of federal ministries from 18 to 9 through a series of mergers, with plans to cut 70,000 public sector jobs;

- ended hereditary positions in the public sector;

- repealed rent control laws, which led to a 200% increase in supply in six months and falling rents (except for the lucky few who benefited from the old regime);

- liberalised labour laws so that the half of the population working informally can move into the formal economy;

- deregulation is being promoted through a new Ministry for Deregulation and State Transformation, which will aim to “reduce public sector employment, eliminate bureaucracy, and privatise certain state-run activities, including public works”;

- slashed subsidies for various activities, such as public transport;

- reduced the income tax threshold to capture more of the middle class;

- repealed tariffs for all imports valued under US$400;

- begun the process to privatise state owned entities such as Aerolineas Argentinas and the rail sector’s main state-run cargo firm; and

- allowed sporting clubs to incorporate, paving the way for private capital to enter the industry.

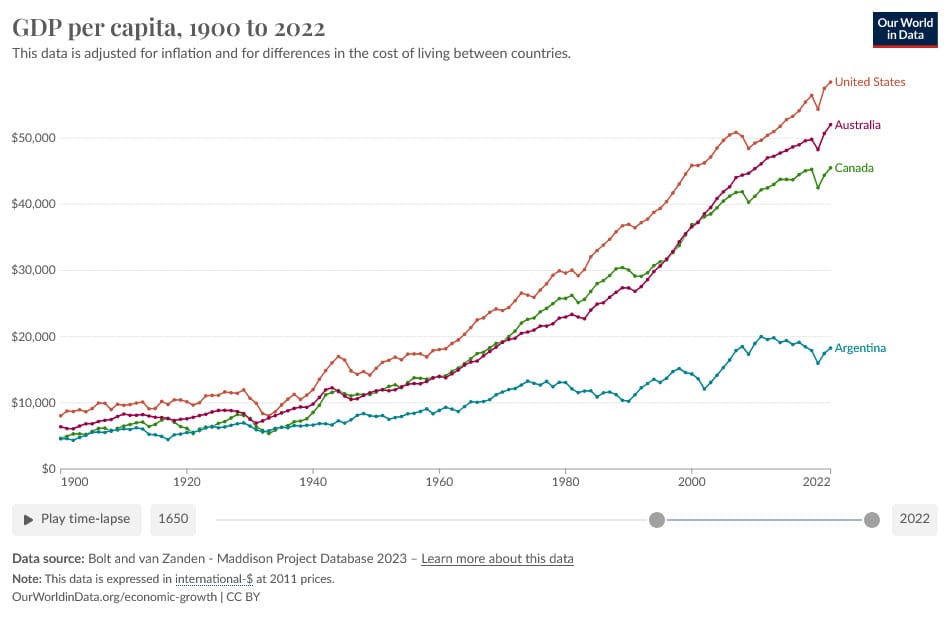

There’s no doubt that the Argentine economy is a mess and in need of something radical. It has been a mess since at least 1930, largely because it “never finished the transition to the open democracy supported by the rule of law”, as happened in Australia, Canada and the US.

Argentina subsequently fluctuated between dictatorship and democracy before Juan Perón swept to power in 1946, establishing a protectionist, planned economy riddled with “government-backed favouritism of dominant interest groups and encouraged pervasive rent-seeking instead of productive economic activity”. Known as Peronism, it has been the dominant political influence in Argentina ever since:

“Starting with the rise to power of Perón and his influential wife Eva, Argentina embarked on an irreversible path of populist social and economic policies and divide-and-rule politics that ignited Argentina’s decline. The institutional breakdowns triggered by powerful elites were chiefly characterised by uninterrupted forced resignations of Supreme Court justices, declaration of economic and political emergencies, nationalisation of firms, prosecution and torture of political opponents, nullification of the 1853 Constitution, rampant government favouritism, and media censorship.

Had the 1930 military coup never happened, and had Argentina avoided the subsequent institutional breakdowns and the populist Peronist-style divide-and-rule politics, the synthetic control and difference-in-differences estimates described herein imply that the country would have experienced a robust upward growth. In the absence of institutional breakdowns, Argentina’s per capita income would have approached the ranks of New Zealand, Spain, and Italy.”

Those are the forces that Milei is working against. He not only needs to transform a hundred years’ worth of institutional malaise, but needs to credibly commit to preserving his reforms beyond his term. That’s no easy task.

A dose of economic orthodoxy

For all the talk of chainsaws and radical libertarianism (anarcho-capitalism), Javier Milei has been rather orthodox in his approach so far.

By that, I mean he’s more or less following the playbook that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) prescribes to most basket case economies facing a crisis:

“We believe Milei is misunderstood as a ‘radical’ figure from an economic perspective, as he is amongst the most economically orthodox leaders that Argentina, and arguably Latin America, has seen in decades. He has already made significant strides in stabilising the economy, and we believe the looming 2025 midterm elections could potentially act as a catalyst for him to gain power in the Senate to accelerate the pace of reforms.”

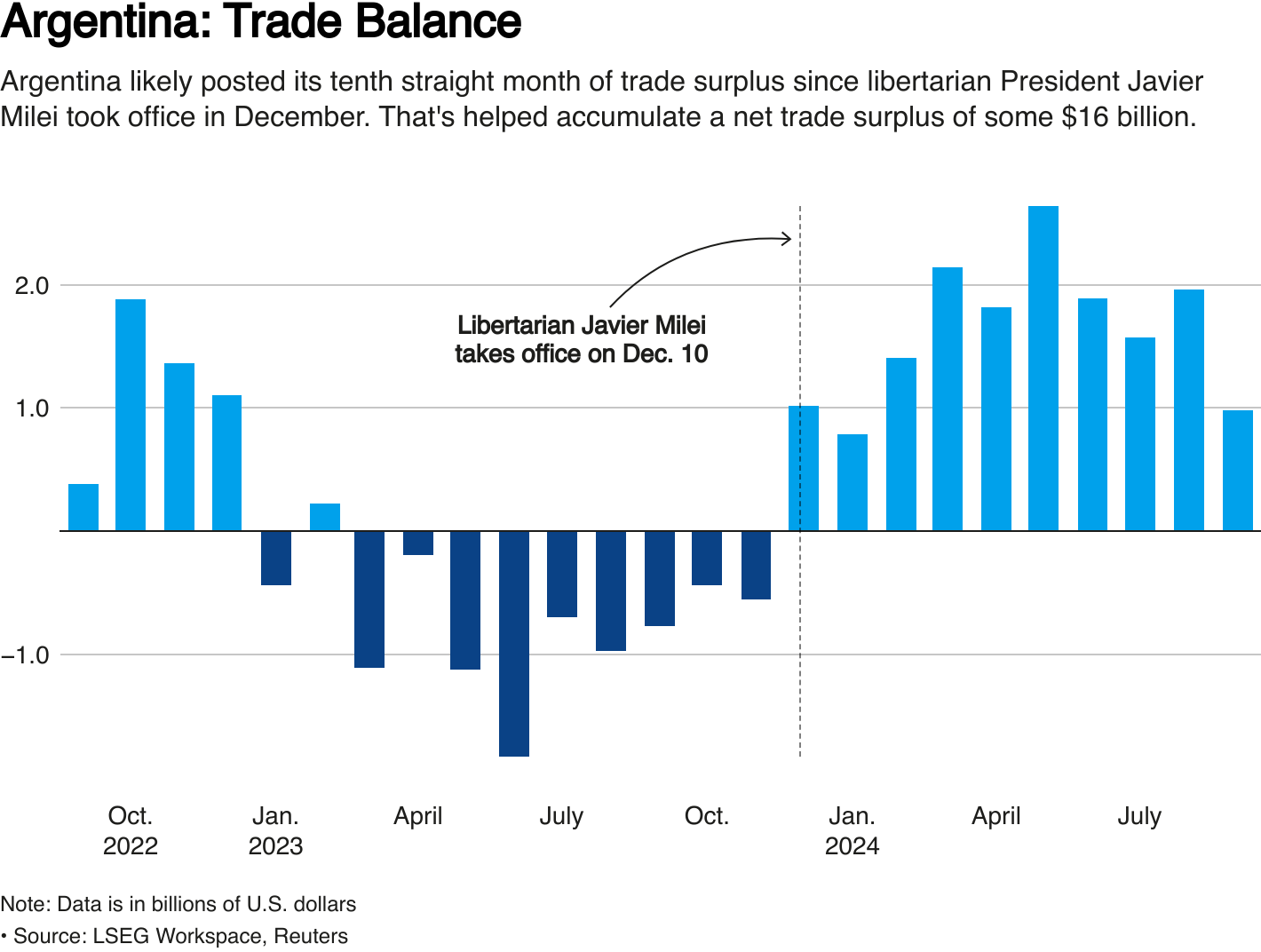

Under Milei, Argentina posted its first budget surplus in 12 years. It has also reduced monthly inflation from more than 25% in December 2023 to 2.7% in October 2024 – still a hugely problematic 37.7% annualised, but certainly better than 1,350%!

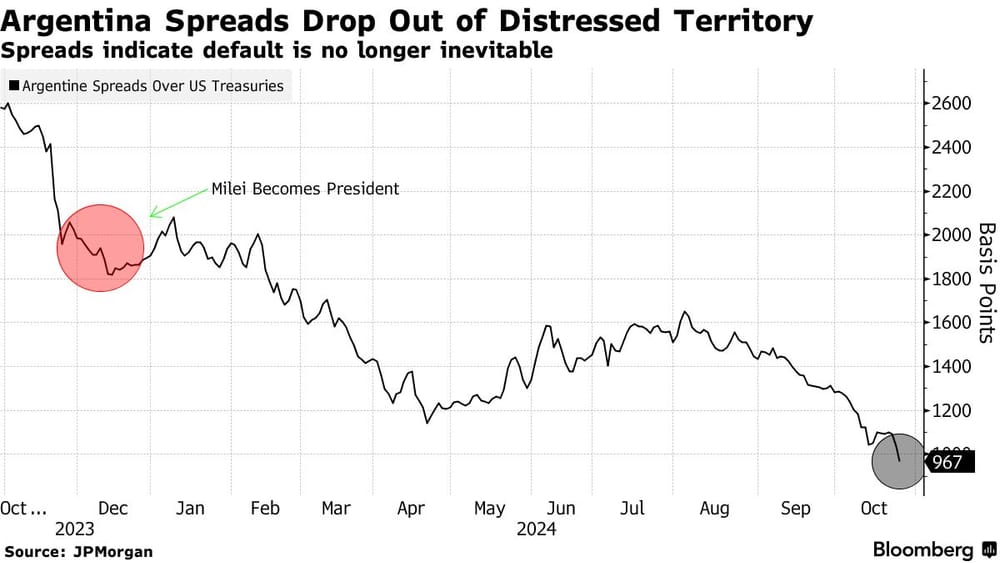

Importantly for Milei’s prospects, real wages are even beginning to recover, and bond markets are no longer pricing Argentina’s debt at “distressed” levels:

The problem for Milei is that it could take years for his policies to have enough of an impact to offset the short-term costs that people are facing. Those tens of thousands of bureaucrats that now need to find private employment? That’s not going to happen overnight. Discontent will gradually build among a decent portion of the population as they begin to realise that they’re poorer than they thought they were. That was all baked in; whether people correctly ascribe the causality to the previous government, or to Milei, will go a long way to determine his success.

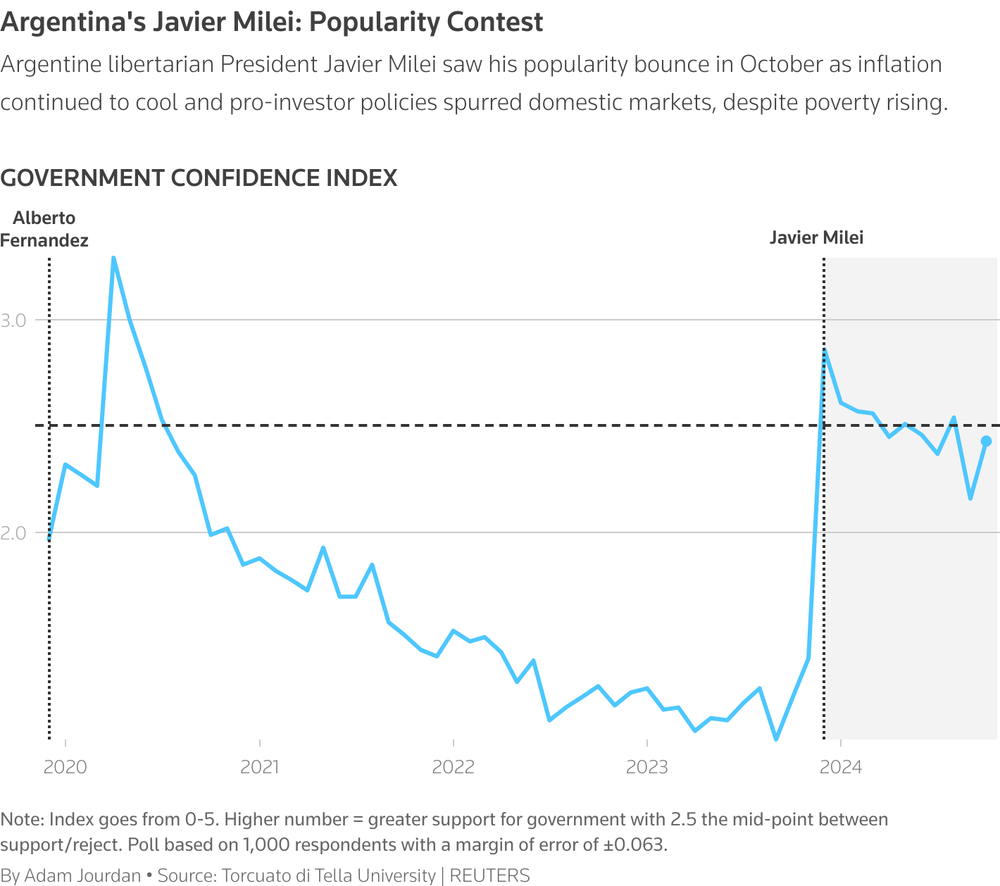

Indeed, popularity is clearly at the front of Milei’s thinking. He has midterm elections coming up in 2025, and given how precarious the balance in congress is, he can’t afford to lose more ground at the risk of becoming a lame duck for two years.

And Argentines are struggling. More than 50 percent of them are living in poverty, the worst rate in two decades, ‘caused’ in part by the huge 50% currency devaluation Milei oversaw early in his term. I put ‘caused’ in inverted commas because it wasn’t Milei but his predecessors that squandered the nation’s wealth and put the currency on an unsustainable path:

Yes, Milei has delivered the reality check in one go by firing government workers, slashing subsidies, ending welfare programs and devaluing the currency. But even if he hadn’t, it’s not clear that Argentina would have been able to maintain the ruse for much longer. Many were already impoverished; they just didn’t know it yet, thanks to debt-financed handouts and price controls that made things “affordable” to anyone that could find them on the empty shelves.

The good news for Milei is that the country’s poverty rate has finally begun to decline. And after plunging in September, his popularity rose again in October:

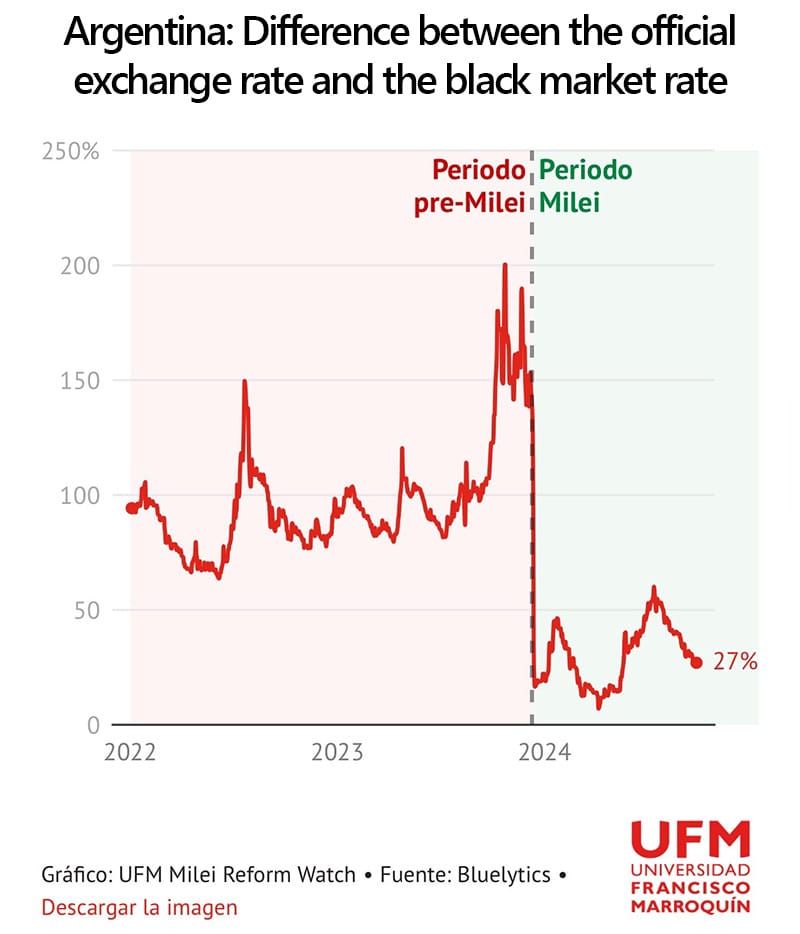

Maintaining popularity is likely why Milei has held off on some of his more extreme policy reforms, such as delaying plans to dollarise the economy until after the midterms. That, and his government has struggled to build up US dollar reserves as it’s spending them “on maintaining the peso’s official exchange rate, in order to prevent a spike in inflation”. It’s a move that’s probably a winner with the electorate, but will increase the time it takes for the painful reform period to finish.

According to economist Roberto Cachanosky, there’s plenty Milei promised prior to the election that he has held off on to maintain his precarious political support:

“One! He promised to dollarise the economy immediately. I want to dollarise as much as he does, but the central bank has no dollars. Two! He promised the IMF would lend him money to dollarise. That wasn’t true. Three! He said he’d cut off his arm before he’d raise any taxes. But he’s raised the PAIS tax [a tax on purchasing dollars], income tax, and fuel tax, and he tried to raise export taxes too. Four! He promised to remove currency restrictions, but they’re still in place. When you export, you should get 1,500 pesos for every dollar you’re paid from abroad [the informal exchange rate is now closer to 1,150], but you only get 950, the rest the state keeps. None of this is liberal!”

The key for Milei is holding on to that support while also avoiding the fate of Chile, which maintained currency restrictions for too long during its own ‘shock therapy’ in the 1970-80s:

“Every month between June 1979 and June 1982, Chile’s domestic inflation exceeded international inflation by a significant margin, generating a growing overvaluation of the peso and a rapid loss in the country’s degree of international competitiveness: domestic costs increased at the rate of inflation, while prices for export goods (when expressed in pesos) rose at the much slower rate of increase of the dollar. As a result, a progressively large current account deficit developed; it was almost 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1980, climbed to 8 percent in 1981, and reached the staggering figure of 14 percent of GDP in 1982. These deficits were financed with short-term dollar-denominated bank loans and other forms of speculative capital. In mid-1982 the authorities could no longer hold the line, and the peso was devalued by 13 percent. This was only the beginning of a process of heightened instability and recurrent devaluations; in the next thirty months the peso lost 70 percent of its value.”

So far, so good – Argentina has run a current account surplus for two consecutive quarters, largely because Milei’s currency controls are significantly less severe than his predecessors’, along with a recovery in the country’s exports:

But Milei is walking a fine line. The longer the rate of inflation remains above the fixed 2% devaluation of the peso, the greater the pressure on the trade balance and risk of a sharp, destabilising currency correction. An artificially strong peso will increasingly deter tourists (although from first-hand experience, the black market ‘cambio’ trade is likely thriving), worry potential investors, and keep Milei’s ultimate goal of dollarisation well out of reach.

But if doing so allows Milei to maintain his popularity in the lead-up to the midterm elections next year by keeping inflation in check (by Argentine standards), then it’s a political calculation that may well pay off, increasingly the likelihood that his reforms will be durable.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!