Monday Musings (1/24)

As a replacement for last Friday’s missing Fodder courtesy of the long weekend, here are a few short takes for you to muse over to start your week, from last week’s happenings that probably didn’t need a full post._

1. An easy-sounding fix for the thorny problem of disinformation

In Friday Fodder ( 2/24 ), I took a quick look at the Australian government’s new interim report on AI safety. One of the three “immediate actions” listed in that report was for the government to “work with industry to develop options for voluntary labelling and watermarking of AI-generated materials”.

It turns out that might be easier said than done:

“Generative AI allows people to produce piles upon piles of images and words very quickly. It would be nice if there were some way to reliably distinguish AI-generated content from human-generated content. It would help people avoid endlessly arguing with bots online, or believing what a fake image purports to show. One common proposal is that big companies should incorporate watermarks into the outputs of their AIs. For instance, this could involve taking an image and subtly changing many pixels in a way that’s undetectable to the eye but detectable to a computer program. Or it could involve swapping words for synonyms in a predictable way so that the meaning is unchanged, but a program could readily determine the text was generated by an AI.

Unfortunately, watermarking schemes are unlikely to work. So far most have proven easy to remove, and it’s likely that future schemes will have similar problems.”

That’s from the Electric Frontier Foundation (EFF), who spend a lot of time thinking about these types of issues. As far as I can tell, every watermarking tech has so far failed to check all the necessary boxes to work in a ’live’ environment, so I’m not sure what the government can really do here without opening a whole other can of worms.

The good news is that there are promising solutions that take a different approach. Rather than watermarking AI-generated content, Nightshade is used by artists to “poison” their original work, making it very difficult for large language models to replicate it accurately:

“Nightshade transforms images into “poison” samples, so that models training on them without consent will see their models learn unpredictable behaviors that deviate from expected norms, e.g. a prompt that asks for an image of a cow flying in space might instead get an image of a handbag floating in space.”

Early days yet but in this space, I would certainly err on the side of being less prescriptive. AI watermarking, if it’s as easy to remove as the EFF suggests, risks creating a false sense of security for “watermarked” content that will inevitably be exploited by malicious actors.

2. Have we passed peak AI?

Or perhaps, peak AI-hype? I often joke around that a good time to pick the top of something, whether it’s a “critical mineral” or “artificial intelligence”, is when an Australian government bureau creates a taskforce to focus on it. For example, in May 2023 Anthony Albanese announced the creation of the Australia-United States Taskforce on Critical Minerals. Since then, prices for “critical minerals” such as nickel and lithium have fallen nearly 30% and 70%, respectively. Then just last week, the WA and NT’s Ministers for Mines/Resources jointly committed to “accelerate discussions” aimed at “incentivising investment”, i.e., new tax breaks or rebates to help keep nickel and lithium miners afloat.

Funny how that happens. Much like “peak oil”, we probably never needed a “critical minerals” taskforce, or the ‘strategies’ we have for numerous other concerns: given a bit of time, the solution to high prices are high prices! And if these minerals truly are critical, the last thing you would want to do is subsidise their use when prices are low.

Moving to AI, in September 2023 we got our very own AI in Government Taskforce. Since then, it has been all downhill: the founder of OpenAI, Sam Altman, has been fired and come back again; and the general outlook for AI – once full of infinite possibilities – looks somewhat less glamorous. The clouds of uncertainty are looming over AI for several reasons, as recently outlined by NYU Professor Emeritus Gary Marcus:

- Lawsuits against the company [OpenAI] are likely to come fast and furious.

- Battles over copyright materials may wind up cutting massively into profits.

- OpenAI lacks both profits and a moat.

- ChatGPT and related systems have a kind of truthiness problem.

- Although the underlying technology initially improved rapidly, leading to a lot of excitement, it may soon, perhaps this year or next, reach a plateau.

- It is still not clear that there will be enough adoption to justify the company’s [OpenAI] stratospheric valuations.

- Word on the street at Davos was that after the Fall drama some companies have lost some confidence in OpenAI.

- The FTC has taken a strong interest in OpenAI.

- Internal tensions [at OpenAI] are likely to remain.

Interestingly, new research from RAND found that the AI tools we have today – e.g., ChatGPT – are no more of a risk to “the potential development of biological weapons” than the regular old internet, because they “generally mirror information readily available on the internet”.

Yep. While AI might make certain forms of attacks more likely (e.g., by improving the speed and quality of Nigerian phishing emails, or developing ‘deepfake’ images and videos), ultimately today’s AI – built on large language models – will only ever be as dangerous as the internet.

3. Why housing breaks people’s brains

When the price of something we desire is “high” – indicating strong demand and/or limited supply – those prices work to ration whatever good or service it may be, ensuring it goes to those who value it the most. But high prices are also a signal that we need more supply – except, for various reasons, in housing, where artificial constraints such as land use zoning prevent the market from performing this important function.

Every economist knows this, yet stringent zoning rules persist. Why? On the weekend, Toby Muresianu published an interesting theory on the topic:

“Housing shortages look very different than other shortages of other goods, and are fundamentally counterintuitive to visualize.”

Toby cites research that shows that with just about any good available today, people understand that when there’s more or less of something, prices will come down/go up. Except for housing, where people struggle to visualise that there’s a supply problem, perhaps because they can see housing everywhere around them:

" A homeowner walking through their neighborhood might think ‘how could there be a housing shortage? I see housing everywhere. In fact, there’s more than there used to be since that apartment went up 5 years ago!’

Humans are extremely visual thinkers. ’ More than 50 percent of the cortex, the surface of the brain, is devoted to processing visual information,’ points out Williams, a Professor of Medical Optics at the University of Rochester. ‘Understanding how vision works may be a key to understanding how the brain as a whole works.’

The good news: we can use visuals to explain the housing shortage, and when people see them they often understand it better."

Toby attempts to do that with visuals such as this:

I’m not sure images like this will convince NIMBYs, but it’s worth a shot - nothing else seems to work.

I’m not sure images like this will convince NIMBYs, but it’s worth a shot - nothing else seems to work.

Do read the full essay and remember that even expensive new housing helps to reduce housing costs by creating a domino effect – for example, when people move into luxury apartments, they vacate housing for those with less wealth than themselves, who then free up housing for those with even less wealth, and so on.

4. The gender ideology divide

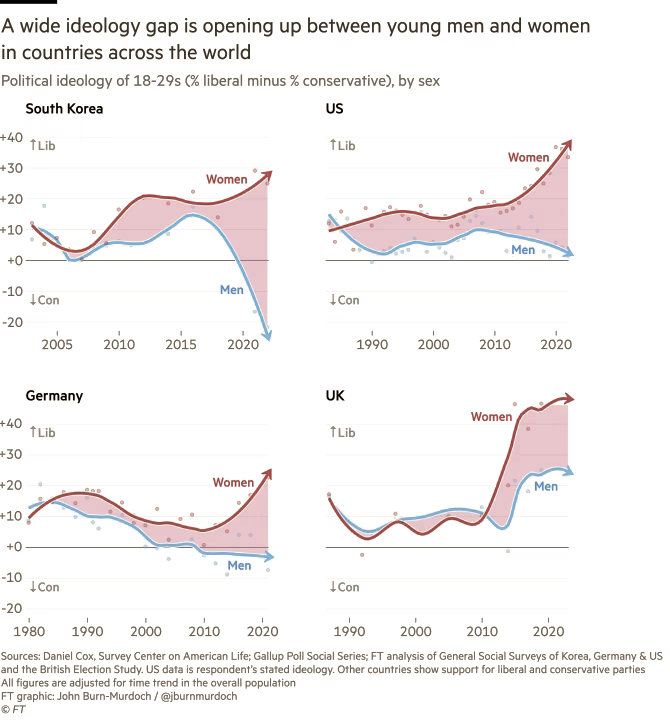

The FT had a very interesting article on Australia Day that looked at a “new global gender divide”:

“In countries on every continent, an ideological gap has opened up between young men and women. Tens of millions of people who occupy the same cities, workplaces, classrooms and even homes no longer see eye-to-eye.”

It included these charts:

According to the FT, except for Germany and South Korea, “the trend in most countries has been one of women shifting left while men stand still”.

This kind of growing divide has obvious political implications, but also important social effects. For example, the country with one of the largest divides – South Korea – also has the world’s lowest fertility rate. It turns out that if “young men and women now increasingly inhabit separate spaces and experience separate cultures”, they also form fewer families and have less children.

5. And if you missed it, from Aussienomics

When will interest rates start coming down?: I fired up my crystal ball and took a bit of a punt on this one. Well, not really, but if you’re interested in my thinking on when the RBA might start cutting rates (hint: not anytime soon) then you should check it out.

Albo’s stage 3 backflip: I’m honestly not sure why Albo was willing to risk so much political capital on a relatively small distributional change just to get his very own Oprah moment. But the whole stage 3 tax cut song and dance is a recurring sideshow to a much, much deeper issue: bracket creep. In this essay I look at fairer ways to do tax policy.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!