Monday Musings (39/24)

Here’s a collection of interesting articles, essays and bits of news I saw over the past week, starting with the most important for Australia: China’s recent efforts to jump-start its ailing economy.

China’s empty bazooka

For the last couple of weeks, China’s government has been on the stimulus warpath, most recently by providing “significant increases to government debt and support for consumers and the property sector”.

But with every round of stimulus comes disappointment for investors, who for whatever reason were expecting President Xi to unleash a “bazooka” equivalent to the ill-fated one rolled out after the Great Recession. I say ill-fated because such stimulus only ‘works’ in the short-term, at the cost of distortions and longer-run wealth destruction.

It has been a wild couple of weeks!

It has been a wild couple of weeks!

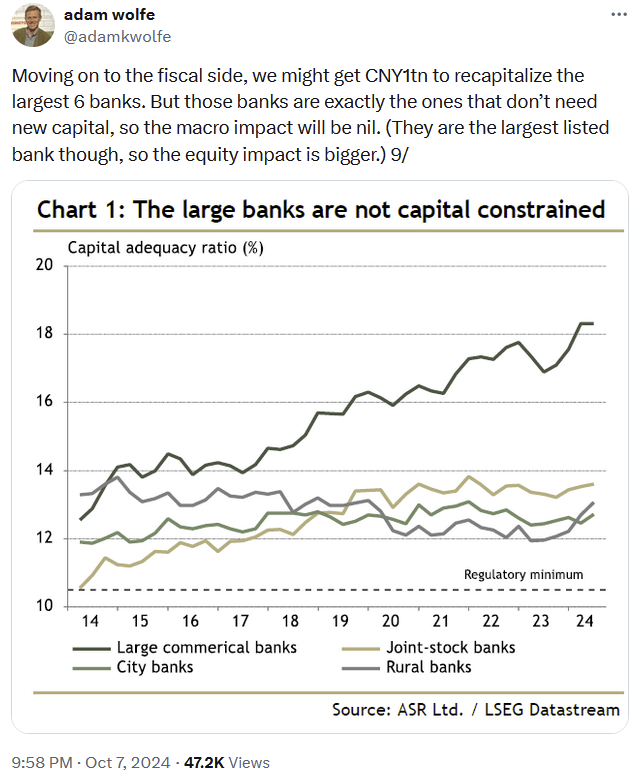

I think it’s a good thing that Xi hasn’t fired the bazooka. China definitely needed monetary easing, some of which will come automatically courtesy of the US interest rate cycle swinging into cuts. But large fiscal stimulus would be counter-productive in an economy that desperately needs resources to be reallocated away from the state, the big banks, and struggling sectors such as real estate, all of which would benefit from stimulus:

But I stop short of agreeing with China pundits such as Michael Pettis, who has long been calling for a ‘forced’ rebalancing in China away from investment and towards consumption via protectionism in advanced economies:

“Pettis saw China’s transformation into the world’s foremost manufacturing power and number two economy facilitated by policies that favoured production and investment by encouraging saving and pinning down consumption. That generated huge trade surpluses that went toward purchasing foreign assets, especially US Treasury debt.

‘I grew up like everyone else thinking, ‘Lucky America, thank God. We don’t save enough, and foreigners are generous enough to give us their savings.’ But looking at it from the point of view of trade and the currency, it became very clear that’s not generosity,’ he said.

Since trade and investment-income surpluses and deficits across the world must equal zero, Pettis argues the US is forced to run trade deficits as long as it absorbs the savings of China and other surplus economies. As those savings flow into US assets, they drive up the value of the dollar. That encourages America to import more, which benefits foreign manufacturers at the expense of jobs and earnings at their US rivals.

And to offset the manufacturing sector’s weakness, the US must borrow more to keep up the big spending, resulting in huge fiscal deficits and periodic financial bubbles.

It is the surplus countries like China, he says, not the deficit countries like the US that are the real protectionists.”

Pettis, like so many others, is confused by an accounting identity, leading him down the unfortunate road to protectionism. But there’s nothing wrong or “imbalanced” with a trade deficit; it simply means that, instead of only exporting goods and services in exchange for imports, a country also accepts foreign investment. Trade is always balanced when capital flows are included.

There’s also no need for “huge fiscal deficits” to “absorb” China’s “excess” savings; if there were no government bonds for China to buy, it would invest in something else, or import additional goods (prices adjust!).

Further, you can’t just magic up consumption; it has to happen organically, flowing from years of saving and productive investment. China has invested a lot, but much of it isn’t all that productive; for every BYD (which probably would have succeeded without government support), there are hundreds of failed EV manufacturers that suck savings away from more productive investments.

For Chinese households to truly consume more, they need to be free to save and invest in more than just the next real estate bubble. In the meantime, its trading partners shouldn’t worry about the deficit; China’s manufacturing subsidies and repression of its savers is effectively a wealth transfer from Chinese households to trading partners, not the other way around.

Undermine encryption at your peril

Law enforcement would love it if encryption didn’t exist, because it would make their jobs easier. Instead of having to do actual police work, they could just wiretap everyone’s messages with dragnet surveillance techniques and pinpoint the ‘bad actors’.

That was the view of Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull back in 2017, the Coalition’s former tech guru because he invested in a mate’s start-up and was lucky enough to get out before the dot-com bubble burst. He infamously claimed that he could force tech companies to give him the keys to their encryption without compromising it, because:

“The laws of mathematics are very commendable, but the only law that applies in Australia is the law of Australia.”

Well, it turns out that the laws of mathematics won after all; you cannot, in fact, put backdoors in encryption without undermining the encryption itself:

“A cyberattack tied to the Chinese government penetrated the networks of a swath of US broadband providers, potentially accessing information from systems the federal government uses for court-authorised network wiretapping requests.

For months or longer, the hackers might have held access to network infrastructure used to cooperate with lawful US requests for communications data, according to people familiar with the matter, which amounts to a major national security risk. The attackers also had access to other tranches of more generic internet traffic, they said.”

Australia’s equivalent legislation passed in 2018 with the full support of the Coalition and Labor. It was used zero times in 2023, and Reece Kershaw, the head of the Australian federal police, said it would be used zero times again in 2024:

“So it sounds as though despite having laws that create compulsory powers, agencies don’t know how or what to compel without voluntary assistance from social media companies. Much of the encryption bill would appear to be practically useless.”

It’s good news that either the anti-encryption legislation was designed so poorly for law enforcement to use, or law enforcement is too technically inept to use it, because if it was being used then the Chinese would probably have had access to our private communications by now, too.

AI and the road ahead

Meta recently demonstrated the ability of its AI to take text inputs and generate custom videos and sounds. Apparently you can simply give it a picture and some instructions and it will create a personalised video for you, which sounds pretty great for those in the film business.

As for the broader applications, here’s what Meta had to say:

“As we continue to improve our models and move toward a potential future release, we’ll work closely with filmmakers and creators to integrate their feedback. By taking a collaborative approach, we want to ensure we’re creating tools that help people enhance their inherent creativity in new ways they may have never dreamed would be possible. Imagine animating a ‘day in the life’ video to share on Reels and editing it using text prompts, or creating a customised animated birthday greeting for a friend and sending it to them on WhatsApp. With creativity and self-expression taking charge, the possibilities are infinite.”

I think it’s a good example of one of the many applications people will find for today’s AI (i.e. large language models). One I’m not as bullish on would be robotaxis:

“Tesla’s strategy relies solely on a combination of ‘computer vision,’ which aims to use cameras the way humans use eyes, with an artificial-intelligence technology called end-to-end machine learning that instantly translates the images into driving decisions.

That technology already underpins its “Full Self-Driving” driver-assistance feature that, despite its name, can’t be operated safely without a human driver. Musk has said Tesla is using the same approach to develop fully autonomous robotaxis.

Tesla’s competitors - including Waymo, Amazon’s Zoox, General Motors’ Cruise and a host of Chinese firms - use the same technology but typically layer on redundant systems and sensors such as radar, lidar and sophisticated mapping to ensure safety and win regulatory approval for their driverless vehicles.

Tesla’s strategy is simpler, and much cheaper, but has two critical weaknesses, industry executives, autonomous-vehicle experts and one of the Tesla engineers told Reuters. Without the layered technologies used by its peers, Tesla’s system struggles more with so-called “edge cases” — rare driving scenarios that self-driving systems and their human engineers struggle to anticipate.

The other major challenge: The end-to-end AI technology is a ‘black box,’ the Tesla engineer said, making it ’nearly impossible’ to ‘see what went wrong when it misbehaves and causes an accident.’ The inability to precisely identify such failures, he said, makes it difficult to safeguard against them.”

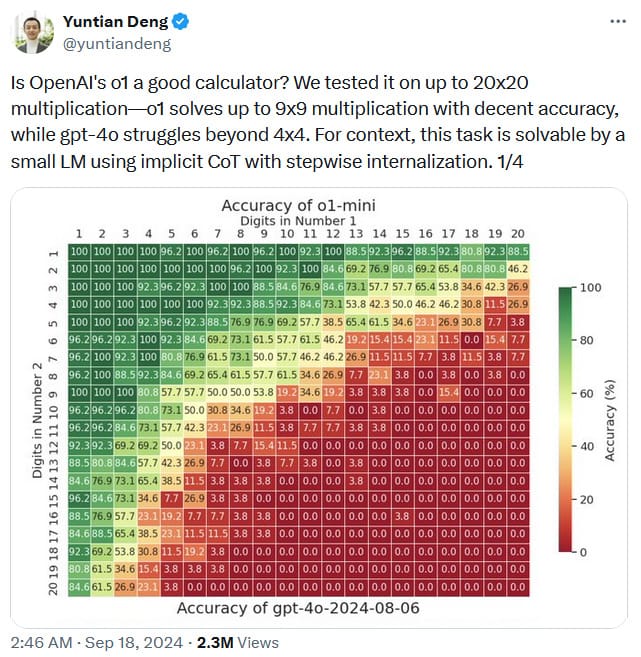

Large language models aren’t well suited for what driving cars on roads full of humans and “edge cases”. And I’m not sure it ever will be, as predictive models are incapable of genuine logical reasoning and so tend to perform worse the more complicated the problem becomes, even in basic multiplication that could be done perfectly with a regular calculator:

I think we’ll get robocabs, but they’ll be driven by Waymo and the Chinese companies that are investing in hardware sensors, not Tesla and its fully software-based solution.

Markets would appear to agree with me if Friday’s stock price movements were any indication of the future prospects of each model (Uber is Waymo’s partner and didn’t announce any market-sensitive news on Friday):

AI is impressive – and is getting better every day! – but that doesn’t mean we’re not in an AI-hype bubble. Elon’s hyped-up cybercabs and the recent move by OpenAI – which was supposedly created to ensure that AI “benefits all of humanity” – to move to a ‘for profit’, so that founders like Sam Altman can cash out more of their equity, strike me as warnings that a lot going on in the AI space might be just a bit too frothy relative to fundamentals.

The World should be against protectionism

The Aspen Institute recently published an interesting paper on protectionism. Specifically how damaging it is and, yes, that includes industrial policies such as a Future Made in Australia. Here are some takeaways:

- Trump’s tariffs reduced manufacturing employment and raised prices and unemployment rates. They also failed at their stated goals of reducing the trade deficit and thwarting China, given many goods were simply rerouted.

- The decline in US manufacturing jobs reflects the country’s relative productivity – workers now have new, better (higher paying) opportunities.

- Industrial policies targeting specific industries will likely have public benefits that exceed public costs. A better approach would be to fund basic research and build productive infrastructure that enables innovation and dynamism more broadly.

As for China, its manufacturing success has come with “overinvestment in many sectors, a deeply imbalanced economy with too little consumption spending, a growth model struggling to transition away from exports, massive overbuilding of real estate, and an inadequate safety net”.

I mentioned above that you can’t sustainable increase consumption spending without first getting productivity up, so more fiscal stimulus will only worsen China’s economic situation. What China needs is for its people to be allowed to save and invest in what they want, rather than what Xi Jinping considers appropriate.

India’s institutional limits

Narendra Modi has been Prime Minister of India for over a decade now – since May 2014. He has certainly improved the situation from the previous mob, but according to Shruti Rajagopalan and Shreyas Narla, it has been far from perfect:

“India’s political economy in transition defies simple explanations based on rankings or anecdotes about corruption. The regulatory legacy of socialist times combined with reform challenges in a federal system complicates matters. Add to this an economic model of picking national champions in a system with high entry barriers and protectionism—cronyism inevitably follows.

These factors have led India to adopt, what Lant Pritchett, Kunal Sen and Eric Werker call, a deals-based economic approach rather than a rules-based one. While this has improved the business environment for some crucial sectors and firms, it has entrenched cronyism further.”

Modi started by pledging to follow a rules-based approach “to tackle cronyism and encourage genuine market competition”. And for a couple of years it worked, with Modi’s government passing competition reforms, establishing an independent central bank, and rolling out a single GST, “eliminating corruption at state borders”.

But over time the opposition and local interests started to coordinate, “paralysing any further economic reforms”. Instead of persisting, Modi – who as any good politician would, wanted to “do something” – abandoned his original model “for a deals-based system, entrenching cronyism, with the government favouring specific sectors and firms instead of broad reforms to ease entry, competition and innovation”.

For India to become an advanced economy, it needs to get back to the rules-based approach. But it’s difficult to see how that’s possible; Modi doesn’t have much time left – he’s in his third term, and is 74 years old – and the last election was close, suggesting there’s now even less of a mandate for such reforms.

A business-friendly but more “deals-based” India might be good for the stock market (large corporates are best-placed to “deal” with the government), but it will come at the cost of long-run growth. And if India’s institutions don’t improve – or regress – it may not bode well for Australia, which stands to gain from an economically-strong and wealthier India through its geographical location, trade openness, and abundant resources.

Fun fact

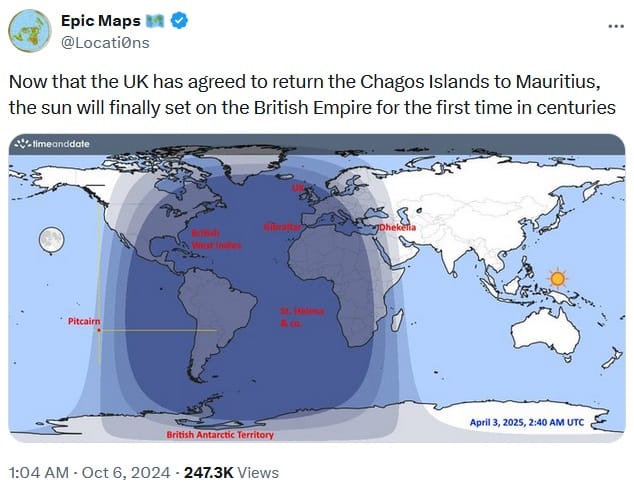

The sun is setting on the British Empire:

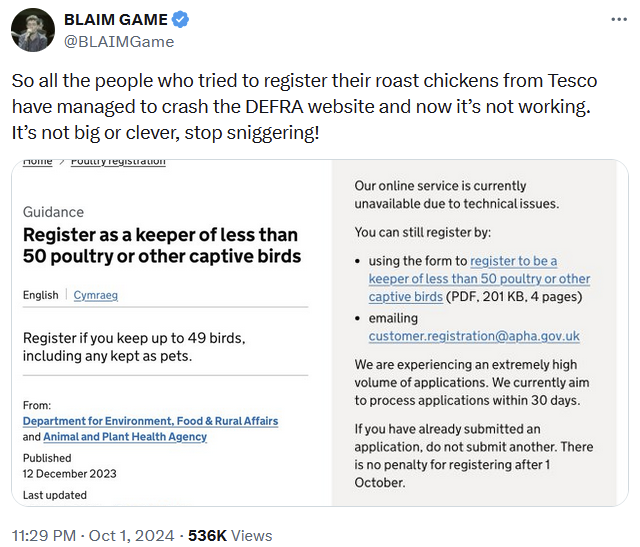

And as a bonus follow-up to last week, the Poms are complying with the government’s new requirement to register their chickens in a way only they can:

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!