Monday Musings (40/24)

Jobs and Skills Australia might see shortages everywhere, but there’s certainly never any shortage of interesting things to discuss here, starting with last week’s booming jobs figures which could have important long-run economic implications for Australia.

Running it hot

Australia’s September labour force data were good. Really good:

“Employment has risen by 3.1 per cent in the past year, growing faster than the civilian population growth of 2.5 per cent. This has contributed to the increase in the employment-to-population ratio by 0.1 percentage point, and 0.4 percentage points over the past year, to a new historical high of 64.4 per cent.

The record employment-to-population ratio and participation rate shows that there are still large numbers of people entering the labour force and finding work in a range of industries, as job vacancies continue to remain above pre-pandemic levels.

While the number of unemployed people fell slightly to 616,000 in September, overall the number of unemployed people has risen by around 90,000 people since September 2023. Despite this rise over the last year, there are still around 93,000 fewer unemployed people than there were just before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the unemployment rate was at 5.2 per cent.”

If the labour market runs hot, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) – whose models include an assumption that there’s a short-run inflation-unemployment trade-off (Phillips Curve) – is more likely to focus its attention on the inflation side of its dual mandate.

So, it certainly didn’t come as a surprise that following the employment release, the market-implied odds of a rate cut were pushed back to at least the 18–19 March 2025 RBA meeting. The Aussie dollar also strengthened nearly a full percent again the US dollar, reflecting expectations of diverging monetary conditions in the two countries.

Basically, the RBA and our various governments are running the economy hot, with the current unemployment rate below the lower bound of the RBA’s estimate of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.

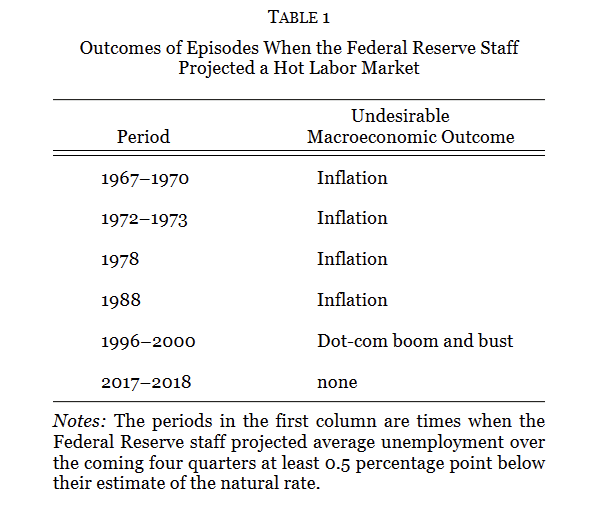

Unfortunately, there’s no evidence that overcooking the labour market is either sustainable, or without consequences. As a recent report by Christina and David Romer found, all bar one episode where the US Federal Reserve prioritised employment over inflation ended poorly:

Another problem with Australia’s strong labour market is that “nearly all the additional hours worked over the past year have been in the non-market sector”, much of which has come from the “care” sector, e.g. NDIS.

Perhaps that’s a good thing – we’re a rich, aging country, after all – but the speed at which the care sector has grown represents a large structural change in Australia’s economy that I’m not sure our policymakers have fully comprehended.

That change has implications. First, the care sector has seen virtually nil productivity growth and the prospects of that changing are slim, which means we’re going to have to increase productivity elsewhere to support overall wage growth. Where are the productivity-enhancing reforms to ensure that happens? We shouldn’t simply cross our fingers and hope for another mining boom.

Second, to the extent that the expansion in this sector is being funded with debt rather than revenue, it means a greater future tax burden (or higher inflation). That will tend to lower productivity growth, especially as Australia increasingly relies on taxing productive activities such as income.

Brickies don’t cause inflation

I would have hoped that after the first major bout of inflation since the 1980s, surely the media would at least put in a bit of effort into trying to understand its causes. Alas, it appears economic ignorance remains as strong as ever, if this story in The West Australian newspaper is any indication:

Inflation is a reduction in the purchasing power of the currency, which manifests itself as a general rise in the prices of goods and services. It is caused by monetary policy, not bricklayers. Fiscal policy has a role to play in the sense that it can make the central bank’s job more difficult, such as by reducing the expected present discounted value of structural surpluses relative to the real value of the public debt.

Brickies don’t play any role in that process. If every bricklayer in the country got together and agreed to raise prices to $5 a brick tomorrow, it would raise the price of bricklaying relative to other goods and services, but inflation – the purchasing power of the currency – would be unchanged.

Now it’s true that some measures of inflation, such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), might show an increase in the short-run. But that’s simply an artefact of how it’s calculated: the ‘basket’ is fixed in the short-run, and it doesn’t capture the substitution effect, e.g. people using more timber instead of bricks because of the change in relative prices, very well.

It’s why when the government subsidises electricity and lowers the price of electricity, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) ’looks through’ the effect that will have on the CPI. It knows that inflation hasn’t actually changed, just relative prices.

It’s not the greedy landlords

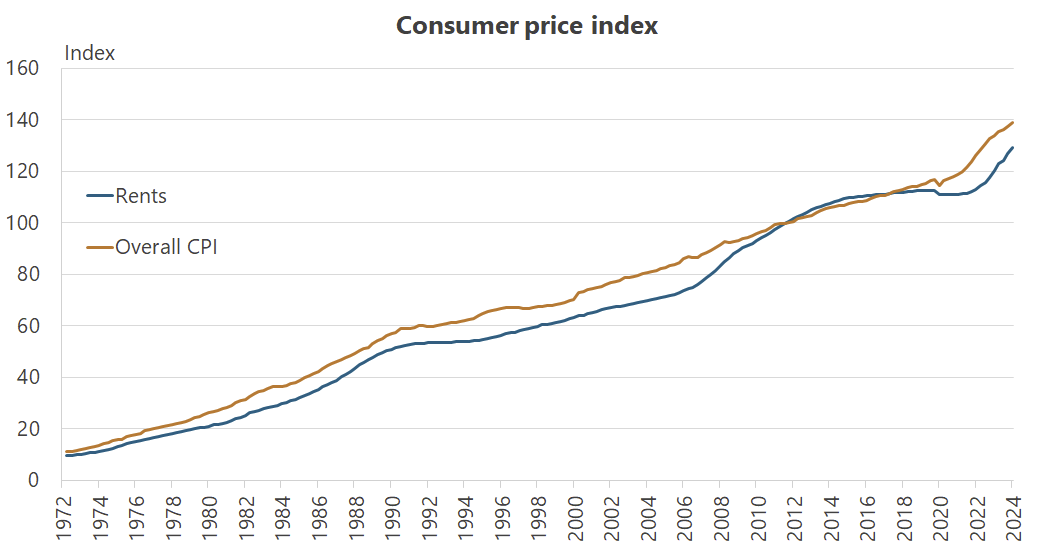

The market for rentals is quite competitive, which is probably why in the long-run rental costs have tracked overall prices relatively closely:

Researchers at the RBA went a step further and looked at anonymised tax data to see if there was “evidence that higher interest rates have been a key driver of increases in rents over the past few years”. They found that there was some, but it pales in comparison to how much landlords’ costs have risen:

“The largest estimate suggests that direct pass-through results in rents increasing by $25 per month when interest payments increase by $850 per month (the median monthly increase in interest payments for leveraged investors between April 2022 and January 2024). Overall, the results are consistent with the view that the level of housing demand relative to the housing stock is the key driver of rents.”

That’s what would be expected in a competitive market, with many landlords competing for many tenants, charging rents based on what the market can bear. In such a market, policies such as rental freezes would be highly distortive, unleashing a wave of unintended negative consequences.

Do we have labour shortages?

Economist Matt Nolan recently took a look at this year’s Occupation Shortage List, a big list of supposed shortages published by Jobs and Skills Australia. I’ve long been suspicious of such lists, because:

- in an economy where 1.1 million people change jobs every single year, how is a central bureaucracy supposed to keep up-to-date with the needs of employers; and

- Australia has a market economy. If there’s a true “shortage”, prices (wages) will rise until that job is filled or pulled.

In a market, a shortage means you can’t get the good you want – or in this case, worker – at any price. For example, if the government imposes a price ceiling on a certain good, and that price is below the market equilibrium price, demand will outstrip supply and you’ll end up with a shortage.

As Nolan notes, Jobs and Skills Australia gets around that inconvenient problem with its methodology by redefining “shortage”:

“Here measures related to labour availability (unemployed), vacancies, and skill complexity - along with a series of employment and population based flow measures - are used to describe the underlying supply and demand of workers in a given occupation.

This measure is combined with survey information relating to firm difficulty finding labour to generate the skills list we make use of.”

That methodology can work for an entire economy when measuring labour market tightness. But when you start to apply it to individual industries or professions, you quickly run into problems:

“Industry by industry, firm by firm, the nature of competition or the structure of the production process could lead to varying patterns of vacancies irrespective of a shortage. But universally, a shortage in one industry should lead to the price of labour in that industry to be bid up.

Using our supply and demand curve above, the shortage should either start to generate rising wages OR we should be able to describe the constraint that is leading to a persistent gap (i.e. public wage setting, monopolistic competition). Once we identify these reasons we can then identify whether there is a related market failure, and use these measures to inform policy.”

Nolan dismisses the latter explanation by simply looking at Australia itself: how likely is it that, given Australia’s vast wealth, that our labour markets are so broken that they “blunt market signals” to the point that we have true shortages? Unlikely, as if we did we would probably be significantly poorer!

Instead, Nolan writes [emphasis in original]:

“[I]f firms are unwilling to put their money where there mouth is to ‘fill a skill gap’, then I don’t really care what random filler text their CFO has put in a survey - there isn’t a real shortage.

Or let me frame this another way - it is sometimes said that wage measures are a poor measure of scarcity as they do not correlate well with these types of constructed measures. But can’t this be interpreted as simply saying that constructed measures are bad?

As price represents scarcity, if your scarcity measure doesn’t relate to price you have a problem - not the price!

If we want a measure that is useful for policy, then we need to know what skills are scarce. To understand what skills are scarce, we need to identify where intense labour market pressure has driven up the returns on those skills.”

Jobs and Skills Australia has a very fancy methodology to measure labour market “shortages”, when it should really just look at prevailing wages rates for specific skills, which would capture all the required information anyway.

As economists like to say, a price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive. If the government wanted to ease labour market tightness, it would scrap the “shortage lists” and instead encourage people to improve their skills where prices (wages) are high, or allocate visa spots to people who already have those skills. Ignore the CFOs who don’t want to pay market wages and let prices do the talking instead!

Victoria’s Potemkin illusion

Victoria’s state government announced a massive zoning overhaul on Sunday:

“Toorak, Armadale, Brighton and Sandringham are among the suburbs where 50 new activity centres – transport hubs zoned for higher-density living – will be designated to help ease the housing crisis.

Taller apartment buildings will be fast-tracked across the 50 sites in a shift that will transform the skyline of the city’s south-east.”

The state’s Liberal party and Teal members such as Zoe Daniel immediately opposed it without offering a reasonable alternative; just pure NIMBYs.

Perhaps sensing the weakness, Premier Allan even had the gall to quip:

“I actually want to thank the local Liberal member, James Newbury and his Liberal colleagues who have come here today because they are demonstrating how we got here in the first place.”

Allan’s Labor party has held power in Victoria for all but four of the last twenty seven years. The housing crisis is her crisis, but because the Victorian Liberals responded in precisely the wrong way, she still feels confident enough to engage in such lines of attack. Hard to see the Libs coming back from this one.

Look, any increase in housing at this point is desirable. But Victora’s policy, which concentrates development solely around various hubs, could have been better. When you only up-zone in limited areas, it creates a weird, unnatural dynamic that riles up local opposition because of the huge, 20-story apartment blocks directly adjacent to detached houses, like this in California:

Such policies also (unintentionally) tend to concentrate transport pollution to where the most people live, which can lead to “asthma, respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, and increased mortality”, offsetting some of the gains in affordability – at least until everyone drives an electric vehicle.

So, it’s a start. And it’s definitely better than doing nothing at all. But there’s a lot of land between these 50 zones where it will remain illegal – either explicitly, or implicitly through the many layers of rules and regulations that drive up costs – to build anything but a single detached dwelling. The so-called ‘missing middle’ of small apartment buildings, duplexes, town houses, and granny flats will remain missing.

Fun fact

SpaceX caught a rocket with giant metal ‘chopstick’ arms, 120 years after the Wright Brothers first achieved sustained flight.

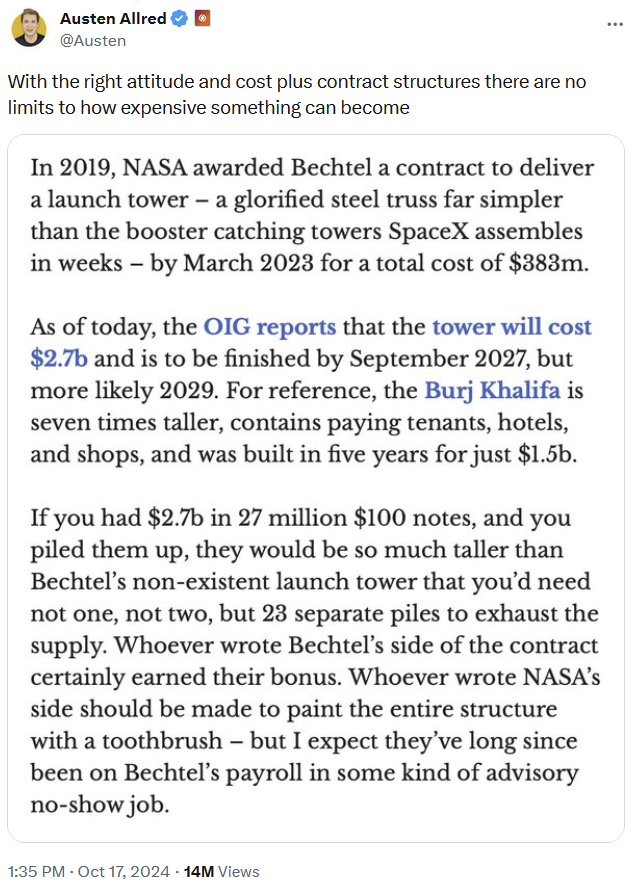

Reusable rockets are innovations that are seriously reducing the cost of space flight. Meanwhile, here’s what NASA is up to:

That’s all for now!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!