Parliament's hectic week, a new era in policymaking, and a glimpse into Australia's future

It was a busy week for the federal parliament, with the government attempting to “ram through” 37 bills in just 4 hours ahead of a long summer break – they don’t sit again until February.

Only one hour of debate was held for a single bill – social media age limits – thanks to a “guillotine motion” negotiated with the Greens and several cross bench senators that suspended debate for the rest. Ultimately, 31 of the 37 bills or amendments passed – 27 bills with the help of the Greens, plus 4 with the Coalition – in what was a sad day for democracy described by independent MP Monique Ryan as follows:

“We need a government that will consider legislation appropriately, with consideration of due process, in a way which is evidence-based and reasonable. What we are seeing right now is not that.”

Thankfully, the worst of the lot – the truly despicable misinformation bill – was not included as part of the guillotine; it was shelved (for now) due to lack of support, along with the destructive plan to tax unrealised capital gains via a new tax on superannuation balances over $3 million, and campaign financing reforms that would have further entrenched the Liberal/Labor duopoly.

But that’s where the good news ends. From an economic point of view, most of what passed were either gimmicks that won’t do much to achieve their stated ends, or will be outright damaging with costs outweighing benefits. For example:

- The questionable Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reforms that split its management into two boards, but now the government will retain the power to override decisions on interest rates, and the RBA will be able to direct private banks how to lend, both of which the review into the RBA recommended against (for good reason!).

- Build to Rent, a gimmick that will do little more than pad the bottom line of developers who were going to build anyway. A late change means it will also ban no-fault evictions, a rule already in force everywhere except WA that is generally considered bad for tenants because it restricts supply, so tends to “exacerbate housing insecurity and lower welfare”.

- Help to Buy, a housing demand subsidy that will benefit a chosen few but make overall housing affordability worse.

- A Future Made in Australia, which is the fancy name for Labor’s revival of industrial policy that will inevitably end up being a terrible waste of resources.

It was also a bad week for democracy, and not just because of the lack of debate and process orchestrated by a Prime Minister who only two years ago promised to act with “integrity, fairness, accountability, responsibility and the public interest”.

No, the real blow to democracy came after the bill mandating social media age limits – which will in practice mandate age verification for all social media users – passed both houses.

While easily bypassed with a simple VPN, the bill " creates a framework that could easily be repurposed for broader surveillance and control beyond age verification", paving the way for the de-anonymisation and tracking of all online browsing and discourse in the future.

Don’t want to hand over your government-issued ID to a foreign social media company? No worries, you just have to let them scan your face instead! For all intents and purposes, by late next year Australian internet may soon resemble China’s.

What’s next, social credit scores?

A new era in microeconomic policymaking

In Argentina, of all places:

“Milei… has broken the mould of previous stabilisation programmes by focusing on microeconomics and institutional reform. Under the leadership of economist Federico Sturzenegger, the government has begun to dismantle decades-old webs of regulation, intermediaries, middlemen and tariffs that stymied innovation, productivity and competition. As a result, inflationary pressures have ebbed as transaction costs have declined.

For example, political organisations such as La Campora, a Peronist youth organisation co-founded by the son of former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, administered many social assistance schemes, building a clientelist relationship with the poor. Milei’s reforms have taken the Campora out of the loop and distributed benefits directly, increasing the net amount that people received. This approach, enacted at the micro level rather than the macro, has been replicated throughout the country, eliminating many of the bottlenecks that have made life so difficult and expensive for millions of ordinary Argentines.”

It takes a long time to get anything done in many parts of Australia because rules and regulations have been expanding, nearly unchecked, for many decades. While each rule might have merit taken on its own, put them all together and they work together to kill off productive activity.

For example, in Sydney planning approval takes an average of three years. Green energy projects can be delayed for so long that the proponents eventually withdraw, citing “extended delays” and “policy ambiguity”. If mining projects aren’t vetoed at the last minute by federal ingenuous or environmental discretion, they can still take half a decade to be approved. Business Chamber Queensland last year estimated that a third of businesses have staff on their books solely to “manage their regulatory compliance”, with the median regulatory compliance costs now $50,000 a year, up from $25,000 in 2021.

To use a metaphor, the growing regulatory burden is like water slowly warming until it eventually boils. The economy can survive for a long time, until it can’t. We’re not yet Argentina, but that doesn’t mean a heavy dose of good old-fashioned microeconomic reform isn’t also needed down under.

Victoria is a glimpse into Australia’s future

If we don’t get our act together, that is:

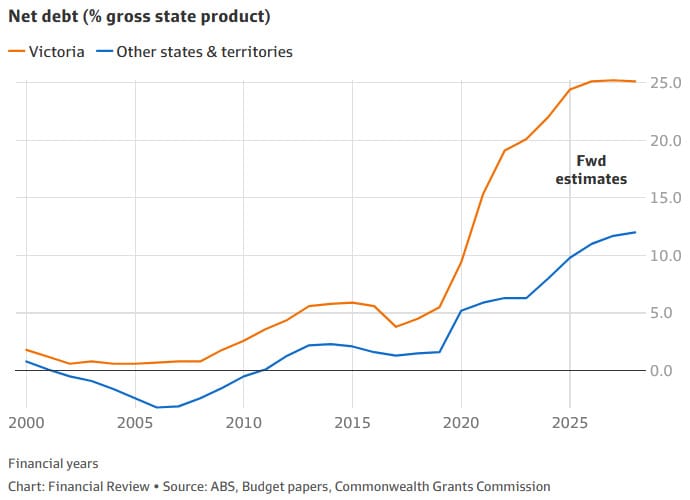

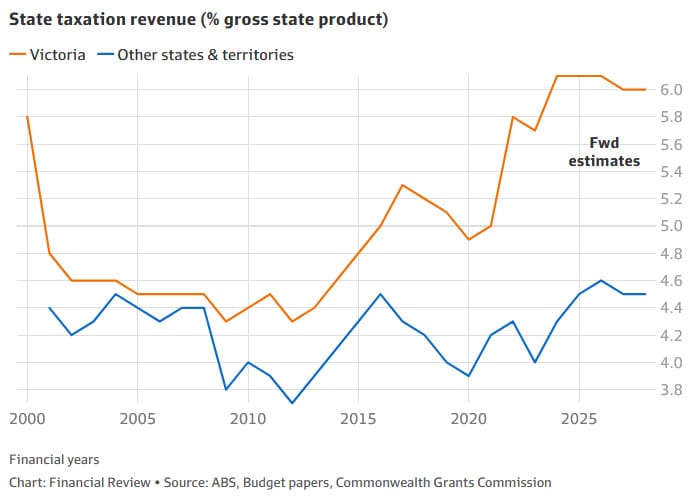

“[S]ince the turn of the century, Victoria’s status as one of Australia’s most prosperous and powerful states has been steadily eroded. It now ranks alongside South Australia and Tasmania as ‘cellar-dwellers’ in terms of relative economic performance; it is the most indebted state or territory as a proportion of its economy; and it has been almost 33 years since a Victorian was last living in The Lodge.

…

The reasons for the decline in Victoria’s relative economic position can be readily identified using the same ’three Ps’ (population, participation and productivity) framework as has been used in the intergenerational reports prepared and published by the federal Treasury since 2001.

That’s from economist Saul Eslake, who noted that the decline isn’t because Victorians work less – more of them work than the national average, and while they work less that has been relatively steady over the decades (all those public holidays!) – but because of below-average productivity papered over with state government asset sales and “persistently larger cash deficits over the past decade than any other state or territory”.

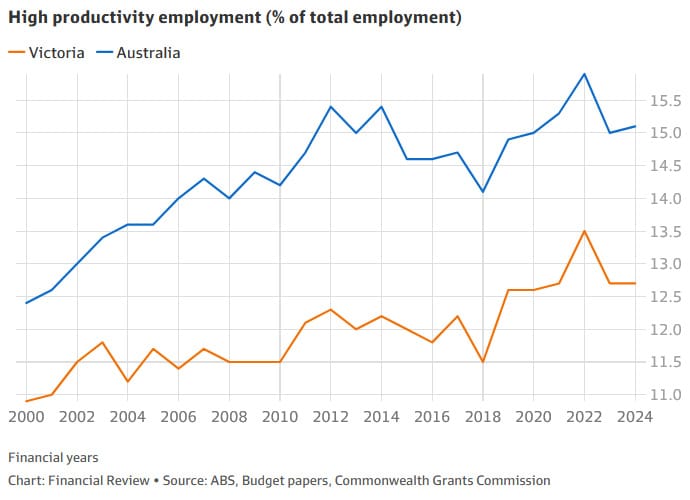

Eslake also offered up over a dozen charts. Here are a few of my favourites:

What Victoria needs is a good dose of Milei. Instead, they seem to enjoy the suffering and persistently elect Peronists like former Premier Daniel Andrews who will keep cranking up the temperature until the entire state boils.

On that note, you may have seen the report from Deloitte that did the rounds this week. It expects the free lunch being enjoyed by federal Labor (and the Liberals before it) to come to an end very soon, with the underlying federal deficit to reach $33.5bn in May 2025 as mining revenue subsides – the largest nominal contraction on record (excluding the pandemic). Here’s Deloitte:

“Over the last two decades both major political parties have fallen short of the standard of fiscal rectitude necessary to ensure the long-term health of the federal budget.

The structural budget position – that is, what the budget balance looks like after correcting for the swings and roundabouts of the economic cycle – is in deep deficit, meaning that without cyclically serendipitous commodity price booms, a surplus is out of reach.

…

[Decades of no reform] has resulted in a coddled and cosseted economy bereft of competitiveness and dynamism.

Economic and productivity growth are moribund and real incomes are declining, while income, wealth and intergenerational inequality has morphed into a broader schism through Australian society.”

As I’ve written before, politicians generally don’t change their stripes unless the “economic or political situation gets so dire that the forces blocking reform fracture, breaking up existing coalitions”.

Until that happens, we’re just going to get more security theatre like age limits on social media, instead of meaningful microeconomic and institutional reform.

Nothing is harder to predict than the future

Venture capital firm a16z recently recorded a podcast on “prediction markets and beyond”, which I thought was an excellent discussion for anyone interested in these things. And you really should be: prediction markets were much more accurate than traditional polling in the recent US election, and this is just the beginning.

Basically, prediction markets are all about price discovery. Everyone has their own model about how to think about the future but that information is dispersed and can be tacit (i.e. difficult to communicate). When a prediction market emerges, it gives people the incentive to reveal that information, with the price of a specific outcome the aggregation and transmission of all that dispersed information.

It’s basically how all markets function, it’s just until recently there was no market for predicting events, and certainly not at the scale we’ve seen recently.

Take an election. If you thought someone had a 70% chance to win, but the market odds are 55%, you would buy and hold the asset. That action pushes the price up closer towards 70%, and the price converges; the difference between what most people believe and the asset’s price is eventually arbitraged away.

But there are even broader impacts. When a prediction market is deep and liquid and the stakes (potential rewards) are high, they increase the incentive to go out and do other work, like discover better ways to poll people, as the French whale did with neighbour polls in the recent US election. If the market is narrow and illiquid (e.g. if bet sizes are capped), you’re not going to do that because your upside is limited.

A smaller market also increases the possibility that the only people swimming in the water are sharks with inside information, and you really don’t want to enter those waters.

As for how to interpret prediction markets, always remember that, say, 60% odds of winning doesn’t mean they’re going to win 100% of the time; it just means that over enough contests – e.g. 100 – where one side has odds of 60%, they should win about 60 and lose 40. It’s the same as flipping a coin: just because the odds are 50/50 and it comes up heads 100% of the time after a single flip, doesn’t mean you should therefore dismiss the theory of probability!

So, what’s next? Prediction markets are expanding well beyond politics. For example, people can use them to bet on which published scientific papers will replicate, improving scientific progress itself – you end up with a profession’s consensus, rather than anonymous referees. It also provides the incentive to replicate when the stakes are high, which has been difficult for traditional academic processes to encourage.

I found the discussion did veer off a bit when they suggested you could use markets to get an idea about the effects of a specific policy. For example, will GDP go up or down after a new immigration policy? To me that’s a bit much; because GDP is so broad and a single policy can be swamped by other forces, you’d just end up with a bunch of diluted GDP prediction markets.

But nonetheless, it was a very interesting discussion about prediction markets and the future of forecasting and well worth a listen if you’re interested in that stuff (and you should be!).

Fun fact

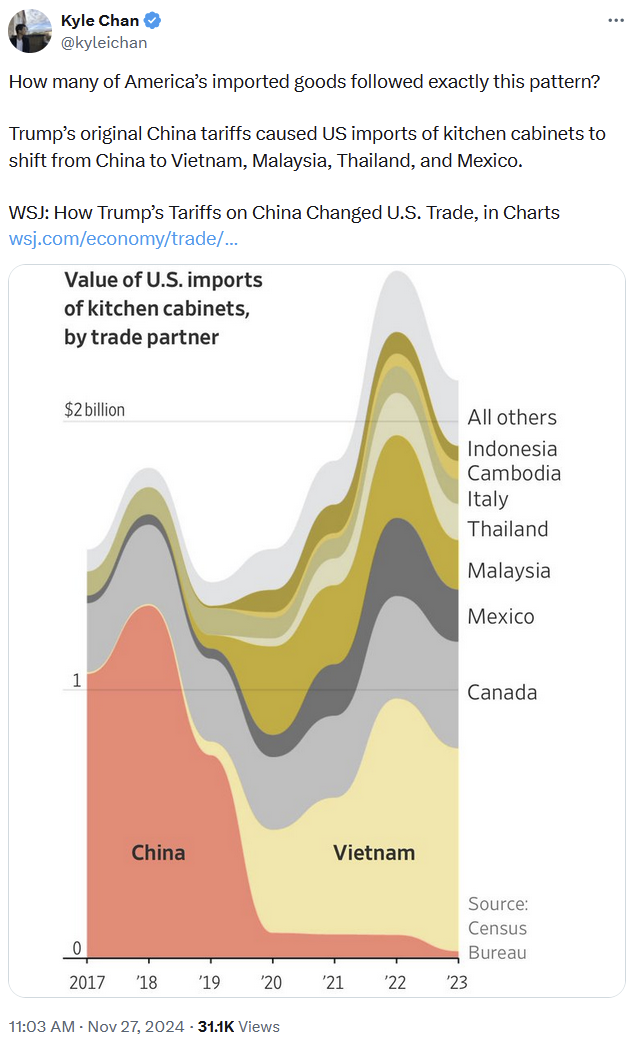

When you restrict trade from specific countries you don’t necessarily stop it, as the flows are gradually redirected at slightly higher cost:

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!