Rate cuts may not help Albo, Cost of living still elevated, We need fiscal rules, and Australia doesn't deserve a sovereign wealth fund.

Sometime this week US President Trump is set to unveil reciprocal tariffs “that match the duties imposed by other countries”. Australia has very few tariffs left these days and has had a trade agreement with the US since 2005, so presumably won’t be targeted (the agricultural exemptions were inserted to protect US farmers, not Australian).

But with Trump you never really know until it happens, so be prepared for anything!

Bad news for Albo

Even if the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cuts the cash rate, as it’s widely expected to do next Tuesday, it probably won’t be the first of many consecutive cuts. What’s more likely is that the RBA accompanies any decision to ease with a relatively hawkish statement, stressing that it may not want to cut too much or too quickly given the considerable uncertainty about the role of subsidies in distorting prices and the robust labour market.

Now, that won’t stop the Albanese government from using it to spruik its inflation-busting credentials ahead of an election that must be held before late-May. But a big problem Albo will have in pushing that message is people don’t care all that much about inflation itself.

Sure, the rate of inflation has returned to something close to the RBA’s target. But prices are up – especially for “core” (trimmed mean) goods and services, and according to new research out of the ANU, that’s what really pisses people off:

“The persistent stickiness of Cost of Living anxiety throughout 2023 and 2024 despite the observed falls in headline and underlying inflation could potentially be explained by the elevated price level. From this, we could speculate that short of an outright deflation episode, a sustained period of low inflation will be required to bring down public anxiety about Cost of Living.

…

We therefore conclude that while we can predict how voters’ policy priorities will adjust in response to rising unemployment rates, we cannot predict with comparable certainty how voters’ policy priorities will adjust in response to falling inflation.”

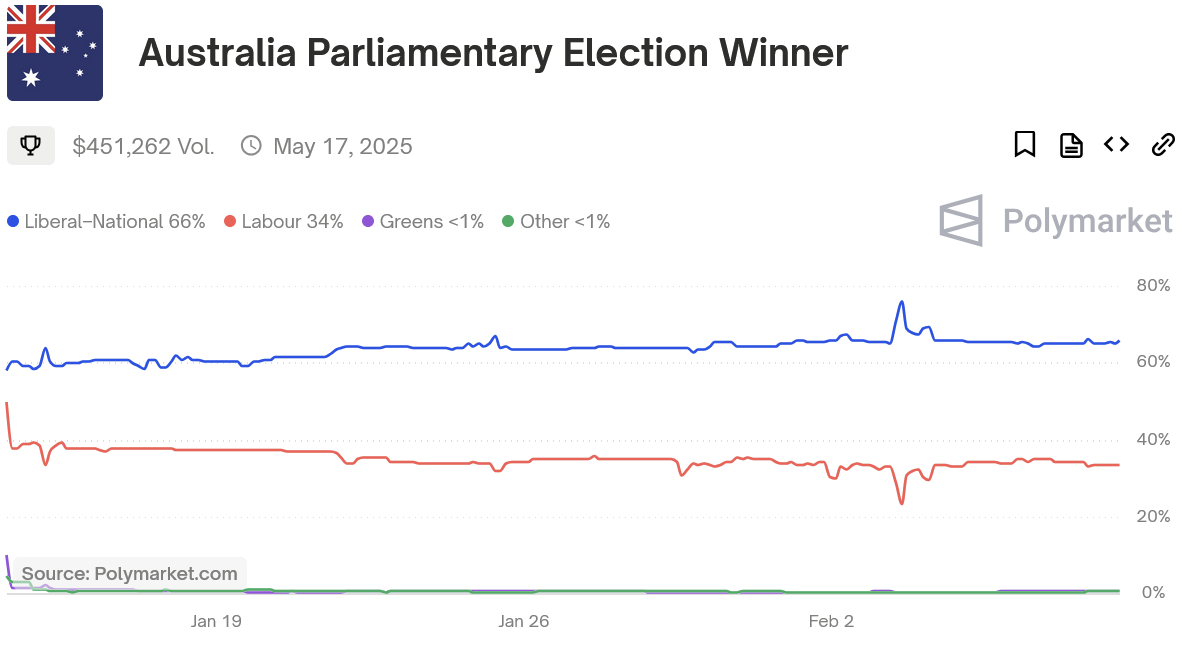

Perhaps that’s why betting markets have had Albo as a slight underdog ever since the market was created:

Voters hate high and unpredictable inflation. But once you’ve presided over inflation for a few years, getting rid of it doesn’t help you (politically) all that much because prices are still elevated.

Cost of living pressures still biting

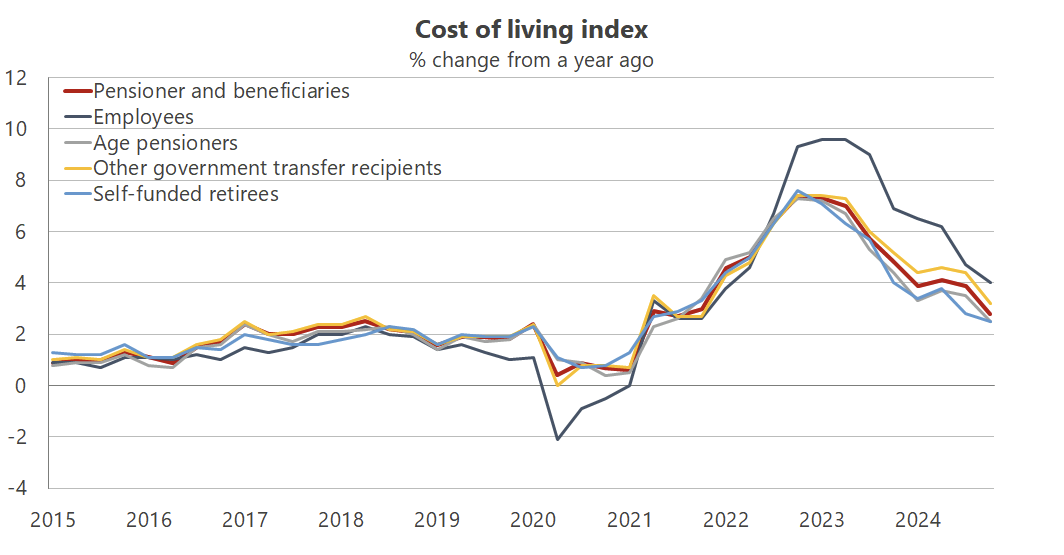

Speaking of inflation, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released its quarterly Living Cost Indexes for December, which unlike the Consumer Price Index (CPI) includes mortgage costs. That makes it a more relevant measure of cost of living pressures in terms of what households are actually feeling.

The good news is that the rate of growth in the cost of living has eased considerably. The bad news is that the annual rate of change (2.0 - 4.0%) is still around twice what people were accustomed to prior to the pandemic (1.0 - 2.0%):

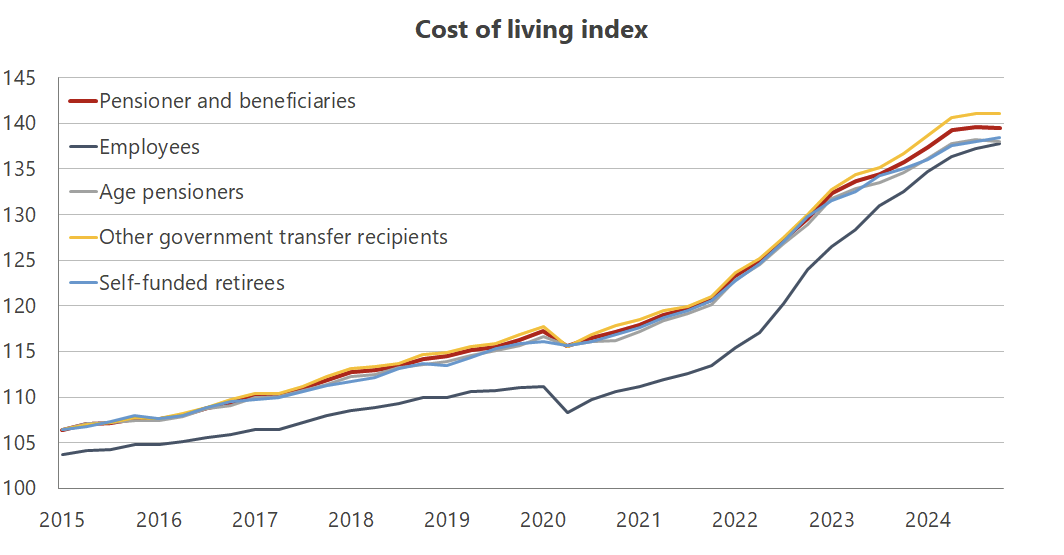

The level is also considerably higher that it was only a few years ago:

The biggest drivers of cost of living pressures are alcohol and tobacco (the government automatically indexes its taxes on these twice a year), recreation and culture, and insurance (which is linked to asset prices e.g. housing).

Looking at these data, I’m amazed the Albanese government didn’t freeze alcohol taxes last year. As one of the big “cost of living” pressure points, it may have helped to win over support of its former ‘working class’ base.

We need fiscal rules

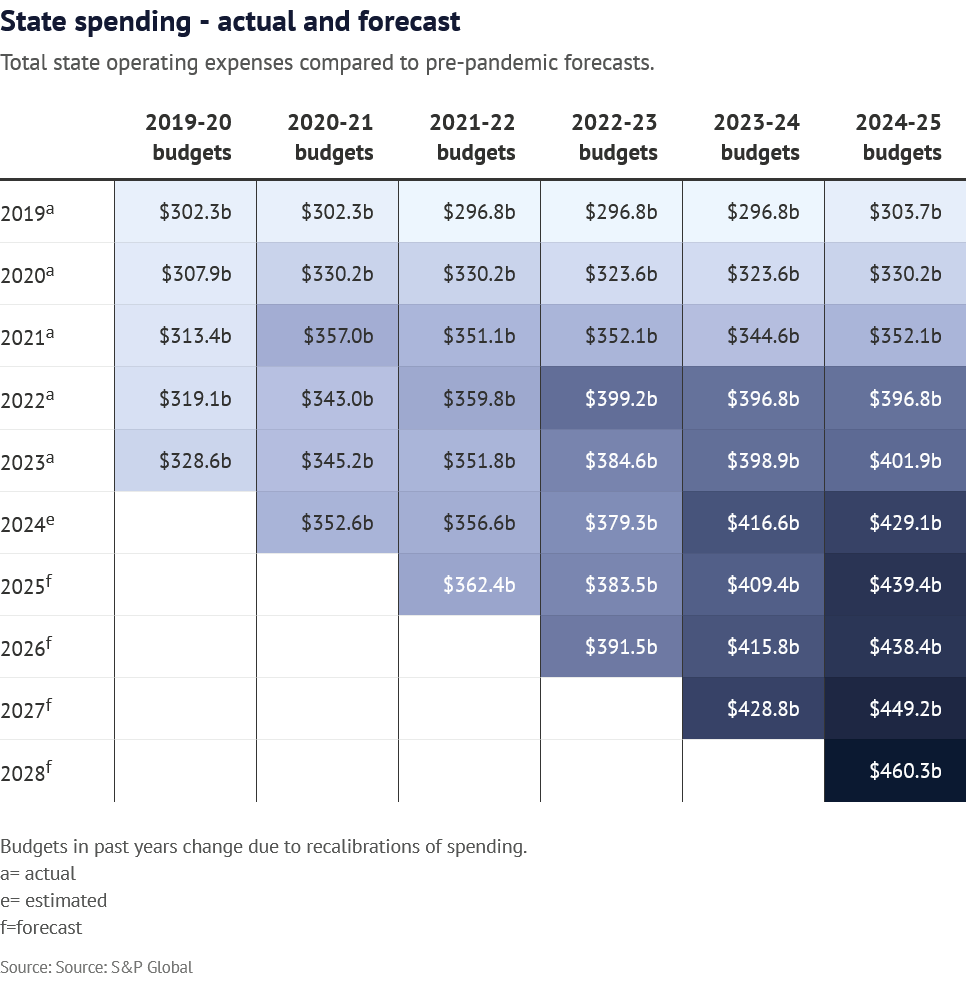

Last week global ratings agency S&P released a report that warned our state politicians have a “spending problem”:

“While states have high credit ratings and have collected record tax revenues since the pandemic, they have failed to rein in pandemic-size spending, choosing instead to prioritise voter-friendly expenditures.

States insist they are making ‘difficult decisions’ or ‘hard choices’.

At the same time, spending continues to rise rapidly, and new projects are regularly announced.”

States have done a poor job at forecasting their expenses:

I’ve warned about our states and their new-found profligacy before:

“It’s time for our states and territories to rein it in, lest we have no fiscal capacity to react to future (inevitable) shocks. And if they can’t be trusted to do that themselves, then perhaps it’s time for some fiscal rules to force their collective hands.”

The reason they get away with it is because they only have two constraints: the ballot box and the federal government. Since the pandemic, neither have been very good checks on power, and given how state governments responded to the S&P warning, I’m not confident they will be in the future:

“State governments have defended their record on fiscal restraint after ratings agency S&P warned some will face credit downgrades for failing to rein in pandemic-level spending.

The treasurers of NSW and South Australia pointed to a reduced growth trajectory for debt while Victoria defended its cost-of-living support, despite S&P’s suggestion that governments were too focused on vote-buying rather than saving money. Labor in NSW and the newly-elected Liberal National government in Queensland blamed predecessors for their states’ trajectory.”

Our states need binding fiscal rules so that when a legitimate crisis rolls around, they have the capacity to deal with it without seeking a bailout from the federal government (i.e. other states).

Unfortunately, it will probably take a crisis before we ever get there: the federal government will need sufficient leverage to get a state to agree to such rules, because these days politicians who believe in fiscal responsibility are rarer than hen’s teeth.

Australia doesn’t deserve a sovereign wealth fund

I’m actually a fan of sovereign wealth funds – when they’re done right. But to establish a successful fund, my view is that you need a few conditions to be present:

- A source of revenue linked to some finite resource, e.g. iron ore, where there’s a strong case to preserve intergenerational equity.

- Structural budget surpluses.

- Binding rules that govern both how the fund itself is used and fiscal rules, so that political borrowing for current expenses doesn’t just increase in proportion to the size of the fund.

Obviously Australia has #1 in spades. But if the fund was to be federal, you would need a way to target specific commodities. Currently federal revenue on commodities is captured indirectly through the corporate tax (a really inefficient way of extracting rents from these resources), so tax reform would be needed to levy something resembling a royalty which, constitutionally, is the domain of states.

On #2, almost all of our governments are running structural budget deficits, not surpluses. There’s a niche argument that, because the government can borrow (issue bonds) at rates lower than the expected return on equities, a well-managed, debt-financed sovereign wealth fund could be in the nation’s interest even if we were running deficits. But as I’ve written before, that’s only if you ignore risk:

“[S]tocks are volatile – the equity premium only exists because of the extra risk – and I don’t know about you, but having bureaucrats taking punts on the stock market isn’t something I’d put in the ‘public good’ basket.”

As Stanford’s Hanno Lustig recently put it, such a strategy only works if a few conditions hold, and none of them “seem plausible or desirable”:

- Treasury investors are naive, can’t do the math, and won’t price in the extra risk.

- You’re about to start Japan-style financial repression to lower your funding costs (e.g. by having the Fed [central bank] buy all of the Treasury issuance), thus taxing ultimately depositors.

- You’re going to offload all of the extra risk onto your taxpayers.

Finally, to make a sovereign wealth fund work in Australia we would need binding fiscal rules (I’m starting to sound like a broken record!).

For example, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund limits the government to spending the expected real long-run rate of return on the fund, leaving the principle in-tact. All withdrawals must be accounted for in Norway’s budget, forcing the government to explain to the electorate why they’re drawing from their future, making it politically costly to meddle with the fund.

The entity that invests the fund is also independent, helping to prevent shenanigans like we recently saw with the Future Fund, where Treasurer Chalmers was able to force it to invest in “national priorities”, i.e. wherever the political winds of the day happen to be blowing.

Basically, there’s no chance of setting up a successful sovereign wealth fund in Australia while we have the politicians we do, and a voting public that seems more interested in the next debt-financed handout than building intergenerational wealth. Cultural norms matter and they change very slowly; unfortunately, the days of Australian politicians that could get elected by upholding norms like fiscal responsibility appear to be long gone.

Fun fact

Australia has a lot of open space:

Our population and housing crises are entirely artificial.

Further reading

- There is no moat (consumers rejoice!): Mistral’s ‘Le Chat’, a France-based open source AI model with a free version, is 13x faster than ChatGPT and was reportedly built for just US$22m.

- The chaos and uncertainty caused by Trump’s on-again, off-again tariff threats will " ripple outward, freezing investment, distorting prices, and disrupting the calculations upon which markets depend. When businesses and individuals can’t predict the basic rules of the game, economic activity is stalled in ways that compound over time".

- If Trump does go ahead with a currency accord, any depreciation is unlikely to achieve the stated aim of boosting manufacturing and exports. Instead, currency depreciations: “appear to juice the economy by raising the return on assets in the depreciating currency. This brings in the ‘hot money’ from days of yore: global capital flows in and borrowing increases, boosting consumption, investment, and service sector growth”.

- A good thread on Canada’s provincial trade barriers. Canada is a very internally protectionist country, that gets away with it (to some extent) by having a huge, free trading bloc to the south. Most of its protectionism is in the form of conflicting regulations that make trade between provinces impossible: “Other than the very stupid rules on alcohol, the so-called interprovincial trade barriers are all *regulatory* in nature. In other words, they’re the result of 10 provinces introducing rules and regulations for all sorts of things and slowly diverging.”

- “The Peter Principle — that people are promoted for their prior success, not their future prospects — is definitely real. Business owners should take heed. What policymakers can do, however, is not as clear. This may be the best we can do, in an imperfect world.”

- Baby bonuses and other government family subsidies tend to bring forward births, but don’t sustainably raise them. The most recent example is from Hungary – which spends around 6% of GDP on ‘pro-family’ incentives – where after a brief rise, the birth-rate is crashing.

- Trump doesn’t care about Australia because we’re an open economy that runs a bilateral trade deficit with the US. Not-so Japan: “On Friday, Trump unveiled plans next week to impose reciprocal tariffs on many countries. It was unclear if they would apply to Japan. [However,] Trump pressed for Tokyo to close its $68.5 billion trade surplus with Washington but expressed optimism this could be done quickly, given a promise by Ishiba to bring Japanese investment in the US to $1 trillion as well as new purchases of US-produced liquefied natural gas, ethanol and ammonia.”

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!