Rethinking the National Broadband Network

Please excuse me if the tone in this post is a bit harsher than usual but I spent all of Monday dealing with my internet provider, which was itself dealing with our local broadband monopoly, the National Broadband Network (NBN) Co, about my persistent lack of internet.

It was a frustrating experience, to say the least, given that I pay for “business grade” broadband – tell me what business can go without internet for an entire day? I certainly can’t. But not wanting to waste a learning opportunity, at least the whole debacle inspired me to do a bit of digging, via a high-speed 5G hotspot connection on my mobile phone, into how and why we ended up with the government-owned corporate monopoly we have today, NBN Co, and what we can do to improve it.

“My greatest contribution”

If you’re not familiar with the history of the NBN, folklore has that it was conceived by then-Communications Minister Stephen Conroy, who scribbled the idea on the back of a napkin when he and then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd were travelling on a plane together. The plan was rumoured to look something like this:

I jest, of course; the napkin has never been revealed, and Conroy denies its existence. But regardless of how the concept was formed, several months later the national broadband network – what would become NBN Co – was born.

Slated to cost $37.4 billion in capital expenditure in a public private partnership, complete its national fibre to the premise (FTTP) rollout by June 2021, and provide the government with an impressive annual internal rate of return of 7.1%, it was “to radically change the way that business is done in Australia”.

Conroy, when he resigned from the Senate in 2016, stated that “the National Broadband Network will remain my greatest contribution”. And that’s saying something, coming from the guy who once boasted to an American investors that he had “unfettered legal power”, and that:

“If I say to you everyone in this room, ‘if you want to bid next week in our spectrum auction you better wear red underpants on your head’, you’ll be wearing them on your head.”

Another great contribution was Conroy’s public ridicule of iiNet’s legal defence against Hollywood (which iiNet won, by the way), and who could forget his attempts to build a mandatory national filter that would even have impressed China and its ‘Great Firewall’.

To be fair, the Liberals of that day weren’t much better, albeit in the other direction. Shortly after becoming Prime Minister in 2013 – yes, only around a decade ago (we really churned through PMs for a while there) – Tony Abbott claimed that:

“We are absolutely confident 25 megs is going to be enough – more than enough – for the average household.”

Oof. That gaffe puts Abbott right up there with the great economist Irving Fisher, who proclaimed in 1929 that stock prices had reached “what looks like a permanently high plateau”, right before they crashed 89% (seriously though, don’t take investment advice from economists).

But I digress. At the time, Labor thought they were onto a winner with the NBN. However, as can often happen when governments try to pick winners, they create losers instead. Today, the NBN is more synonymous with complaints from users of all political stripes, whether due to its glacially slow rollout, poor speeds, high costs, or frustrating lack of reliability (as I experienced on Monday).

And yes, our fixed-line broadband internet is really that bad. According to the World Broadband Association’s 2023 report:

“Australia’s challenges in broadband are widespread, given it has below-average scores in all three broadband segments. The country’s broadband access score is pulled down by relatively low FTTP coverage of 26% and FTTP penetration of 17%, although it is helped by 79% of households having broadband service. The low fibre penetration is one of the factors behind the country’s low score in broadband usage and application, given that fewer than one quarter of the country’s residential broadband connections provide 100Mbps or faster speeds, based on Omdia’s analysis. Its broadband potential score, meanwhile, is impacted by below-average broadband affordability.”

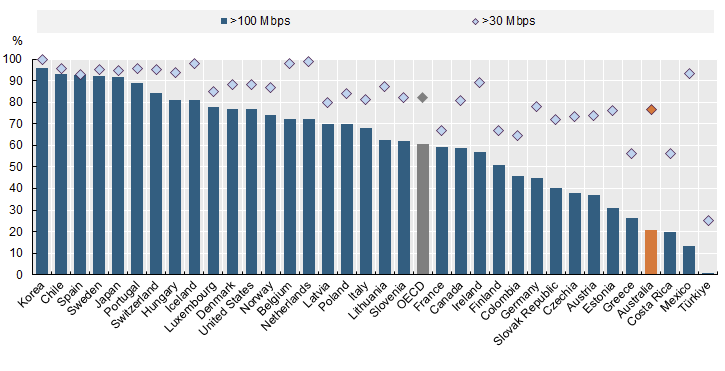

As at December 2022, our internet ranked as one of the slowest in the OECD in terms of the percentage of fixed broadband subscriptions with speeds faster than 100Mbps, which was achievable with the technology Optus and Telstra were already using prior to the NBN (Hybrid Fibre Coaxial, or HFC, more commonly known as cable).

Not all of this is the fault of Labor, or the NBN Co. In 2013, Abbott’s Liberal Party scrapped the plan for near-universal FTTP but otherwise left the existing market structure intact, effectively condemning us to slow and inefficient fixed-line broadband, rather than just inefficient.

Ultimately, the cause of our relatively poor internet performance lies in the way the policies governing the NBN, and Telstra before it, were conceived, designed and then modified over the years by various politicians.

The economics of fixed broadband internet

Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, Godfather of the NBN, likes to claim that broadband internet “is a public good – like highways, railways, schools and hospitals”.

But such statements only serve to confuse: a public good is something people can use without paying for it (‘free riders’); is non-excludable (I can’t stop you using it); and non-rival (my use is not affected by your use). For those reasons, such goods tend to be under-supplied by markets.

None of the examples Rudd listed are public goods; if you want a public good, you need to think more along the lines of asteroid defence, the military, or certain public health issues. Regarding fixed line internet, we all pay, and expect to pay, for access, regardless of whether the government or private companies provide it. Your usage affects mine (it’s why peak speeds tend to be slower than off-peak), and broadband providers can exclude whomever they want from using it.

In other words, it’s not a public good – sorry Kev!

But fixed broadband internet does require considerable physical infrastructure and could be considered what’s known as a natural monopoly, because it would be a lot cheaper for a single company or government to invest in all the fibre we need, achieving economies of scale (costs fall as production increases), than having multiple firms lay multiple cables.

Whether that would still apply today given the considerable competition from new technology such as 5G and low-orbit satellite is a big question – technology can quickly render even the hardiest natural monopoly obsolete – but you could have plausibly made the case on 7 April 2009, when Rudd and Treasurer Wayne Swan announced the NBN, that Telstra and Optus had something resembling a natural duopoly on broadband internet.

Now, I’m not going to bore you with the various methods economists have for dealing with such natural monopoly situations, except to say that they range from government ownership and control on one end of the spectrum to contestable markets and private ownership kept in check by access regimes and antitrust regulations on the other. Since the productivity-boosting 1990s microeconomic reform era, Australia has usually opted for the latter option.

A taste for industrial policy

The NBN marked a deviation from the standard model, with the government electing to own the entirety of the fibre broadband infrastructure, going so far as to buy up the old Optus and Telstra copper to prevent them from competing with the NBN.

To an economist, that move alone was a huge red flag that there was no natural monopoly that justified the creation of the NBN – in such situations, preventing new competitors from entering is unnecessary because no one would want to enter.

So we should consider the Rudd/Swan/Conroy plan as something more like ‘industrial policy-light’, which is consistent with what Swan said at the time:

“I believe this is a responsible investment. We are establishing a commercial entity; we are putting it together on commercial terms; and it should give a return over time to the Australian people.”

By controlling the nation’s fixed broadband infrastructure, the government could effectively set a uniform wholesale price, cross-subsidising places that are more expensive to service with broadband, such as regional Australia, with its more profitable metropolitan services. Competition would occur on the service, rather than infrastructure, side.

But there were a few issues with the concept, even going beyond the lack of clear market failure or evidence of natural monopoly.

First was the timing: building a fibre network in Australia was no easy task, and by eliminating the competition the government effectively condemned a large part of Australia to snail-paced DSL (8Mbps) until the NBN was ready, given that Telstra and Optus, having had to divest their assets, would no longer invest in fixed line services themselves.

However, when there’s a profit opportunity there’s always an entrepreneur willing to step in. While incumbent providers like Optus and Telstra were barred from competing, new entrants like TPG and Uniti filled the gap by building their own high-speed networks. Acting quickly enabling them to achieve scale and network effects that proved hard for the NBN, with its cross-subsidy provisions, to crack when it eventually got around to servicing those areas. In response, the government again proved with its actions that there was probably no natural monopoly, ordering TPG and Uniti to raise their prices to match those of the NBN’s. Not doing so would have undermined the ability of the NBN to earn a commercial return, causing a further write-down of its market value.

Second was the cost: was it really a smart use of our scarce resources to spend tens of billions of dollars to build something that the private sector could, and was, doing? What was the opportunity cost? I get that the desire to connect “every household” to fibre might lead some to respond in the affirmative, but there was never really an economic rationale for it. The privatisation of Telstra in 1997 and its subsequent behaviour complicated matters because the government left it whole, rather than splitting its infrastructure assets and retail operations, but that could have been resolved in ways other than by nationalising its existing assets and building an entirely new fibre network.

The plan was not short of critics at the time, either. Perhaps the most prescient of them was Crikey’s Bernard Keane, who was willing to “bet good money the level of private participation is well below 49%, and that when it’s sold off, the network value will be treated as a sunk cost and there’ll be no return for taxpayers’ money beyond the [net present value] of access charges for retailers”.

From what I can tell, today all of the NBN’s $29.5 billion in equity and most of its $21.5 billion in debt is held by the government. In 2022, the Productivity Commission (PC) estimated the fair market value of the NBN to be just $19.7 billion, although even that was only achievable because of the privilege “NBN Co enjoys as a result of its government ownership relative to its benchmark cost of debt”.

The PC also warned that the NBN will never achieve full cost recovery and “is unlikely to earn a commercial rate of return in the future”, which is why last year the government agreed to NBN Co’s “substantial concession” that it “will not recover over $31.5 billion of its accumulated losses”, reducing its initial cost recovery account from $44 to $12.5 billion. If the government had not done that, prices for consumers would have had to increase by a lot.

The NBN may never be sold off but Keane was right: taxpayers will never see a return on their equity.

We should get creatively destructive

So where to for the NBN Co? It’s already facing stiff competition in the regions from rival technologies such as Elon Musk’s Starlink, which charges $139 a month (after a hefty set-up fee) for speeds equivalent to the NBN’s 100Mbps plan (~$80/month).

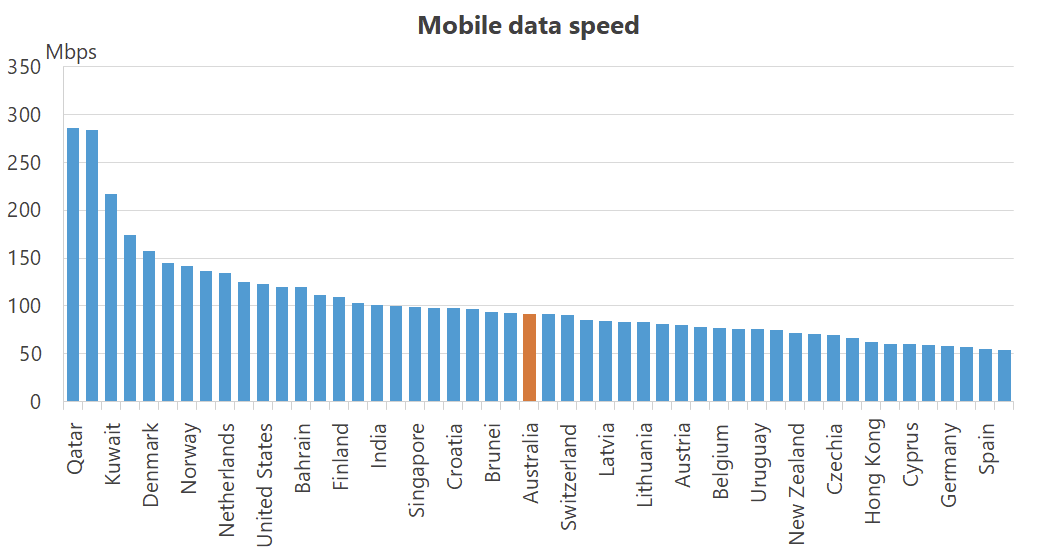

In our cities, 5G is proving quite compelling, both in terms of cost and speed; according to Ookla, which runs a popular speed test service:

“Australia now has some of the fastest mobile speeds in the world… This success is due in large part to the years Australia and its mobile operators have spent investing in 5G infrastructure across the country. Australia is primed to continue to be at the forefront of global 5G performance in the future, as well, with increases in 5G deployments and recent spectrum auctions in the works that will only expand access for Australian 5G consumers.”

Median 5G speeds in Australia range from 185-310Mbps, depending on the provider, location and time of day, and the price should certainly be lighting a fire under NBN Co: Optus, for example, currently has an offer for uncapped speeds and unlimited data for just $79/month, and Australia now ranks in the top 25 in the World for mobile data speed (we’re 94th for fixed broadband):

That competition has, and will continue to, undermine the stated purpose of the NBN to provide high-speed broadband internet to every Australian on commercial terms. It doesn’t make any sense to continue throwing good money after bad, so the first thing the government should do is stop cross-subsidising those in the regions by charging metropolitan users more than they should be paying; just get them to sign up to Starlink!

If a subsidy is needed to get certain regional politicians onside, then do it by postcode.

The cost of continuing on with the current model, both in terms of the required capital expenditure and welfare loss from the cross-subsidy, but also the loss of dynamism that comes from having a monopoly broadband provider that actively tries to stamp out the competition and raise prices for consumers, is significant and should not be ignored.

But if we break up the NBN Co’s business model, the policy question is then what happens to its fibre monopoly? Personally, I think the cleanest and most efficient option would be doing what should have been done with Telstra back in 1997: remove its legislative protections against competition, draw up a fair access regime that doesn’t disincentivise investment, and then auction its assets off, in pieces, to the highest bidders.

Will the government lose most of what’s left of its $19.7 billion fair value? Probably, as a lot of the infrastructure it has built will be unprofitable without the cross-subsidy and various artificial barriers to competition that come with its government ownership and monopoly privilege. But that cost is sunk, and it’s only a secondary concern anyway: if what we’re after is a globally competitive broadband industry that will work best for consumers, then we should try to ensure the sector is contestable, encouraging technological innovation and a mix of broadband options for various use cases.

On that note, I’m going to end with a quote from the ACCC’s former chair Rod Sims, someone with whom I have been critical in the past, but at least on this issue he was spot on:

“What we must never do, however, is seek to restrain others in order to protect the NBN business model. This would be a disaster for consumers.”

Couldn’t have said it better myself.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!