Saving the planet could make some of us rich

It’s only 54 days until Donald Trump becomes President of the US for a second time, and already he’s ruffling more than a few feathers. And not in a good way, I might add:

“As everyone is aware, thousands of people are pouring through Mexico and Canada, bringing Crime and Drugs at levels never seen before. On January 20th, as one of my many first Executive Orders, I will sign all necessary documents to charge Mexico and Canada a 25% Tariff on ALL products coming into the United States, and its ridiculous Open Borders.”

Trump’s nominee for Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, told reporters that these tariffs will be used as “a useful tool for achieving the president’s foreign policy objectives”:

“Whether it is getting allies to spend more on their own defence, opening foreign markets to US exports, securing cooperation on ending illegal immigration and interdicting fentanyl trafficking, or deterring military aggression, tariffs can play a central role.”

Right, so tariffs first, negotiate later, and in the meantime the wealth-destroying effects of tariffs will be felt by Americans and the world – Mexico has already vowed to retaliate, as has Canada’s opposition leader and likely next Prime Minister Pierre Poilievre (Justin Trudeau has called an emergency meeting, so expect something there too).

To be clear, tariffs are bad for everyone. But they’re worse for for small, trade-exposed countries like Canada and Mexico – and of course Australia – than places like the US, which have huge internal domestic economies that can absorb some of the worst impacts.

It’s in times like these that I’m thankful we have a cool, level-headed ambassador appointed to Washington to smooth things over in the form of… Kevin Rudd. Yikes.

Anyway, on to the main topic for the day. The title of this post is a slightly reworked version of a recent Ross Gittins column, in which he claimed that “playing a major role in saving the planet could make us rich”.

Notice my subtle addition of “some of”, with the implication that many of us could actually be made poorer if we follow Gittins’ plan to save the planet. Clever, right? Maybe not. But it’s surely more intelligent than the rest of the Gittins column, which gushes over “new evidence” commissioned by a think tank run by two former high ranking bureaucrats, Ross Garnaut and Rod Sims:

“Finighan’s report, The New Energy Trade, provides world-first analysis of likely international trade in clean energy and finds Australia could contribute up to 10 per cent of the world’s emissions reductions while generating six to eight times larger revenues than those typical from our fossil fuel exports.

He demonstrates that, though Australia’s present comparative advantage in producing fossil fuels – coal and natural gas – for export will lose its value as the world moves to net zero carbon emissions, it can be replaced by a new and much more valuable comparative advantage in exporting energy-intensive iron and steel, aluminium and urea, plus green fuels for shipping, aviation and road freight, with our renewable energy from solar and wind embedded in them.”

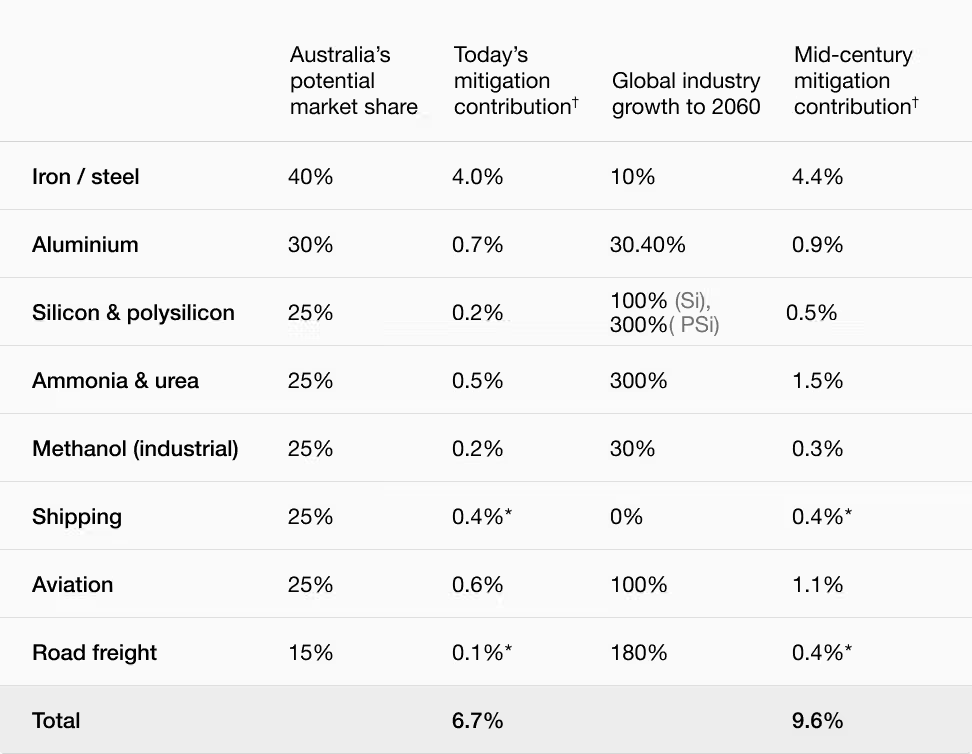

The world currently produces around 2 billion tonnes of steel each year. The report Gittins cites makes the bold claim that with the right policies, Australia could one day claim 40% of global “iron/steel” production – which broadly corresponds to how much steel is currently made using Australian iron ore, mostly in China.

At risk of over simplification, the author basically assumes that 100% of Australian iron ore will be used to make green “iron/steel” in Australia instead of being exported as raw ore, works out the difference in price between the two, and concludes we as a nation could make hundreds of billions of dollars each year if only we had the will to do it.

Earlier this week I wrote about some of the problems with that idea. The author of this 126-page paper did not feel the need to consider any of them. Also concerning was the use of “iron/steel” throughout the report, which I can only assume was designed to confuse journalists such as Gittins:

But what the report is discussing when it mentions “iron/steel” is not green steel, but “green processing of iron ore into iron metal, and perhaps also steel, before export”.

“Perhaps”? As for “iron metal”, that would be direct reduced iron (DRI), a key ingredient in the steelmaking process. But unlike iron ore, DRI “has a tendency to re-oxidise, an exothermic reaction” – i.e., catch fire – and needs to be “shipped under an inert atmosphere, usually nitrogen”.

Presumably that will make the logistical challenges I discussed even more costly to mitigate. But none of that is considered; the author simply assumes that it’s possible without cost, and that there’s free money available if we’d just do it (emphasis in original):

“Iron production most clearly benefits from Australia’s comparative advantages, as the most energy-intensive and least labour-intensive step in the steelmaking process. A typical price for direct reduced iron is around US$450, or AU$690, per tonne. Australia’s recent exports could be converted into around 560 million tonnes of direct reduced iron, for a total revenue of around $386 billion. Because iron ore would no longer be exported, the actual export revenue gain would be $75 to $100 billion lower. Taking a middle value, the increase in export revenue is around $304 billion.”

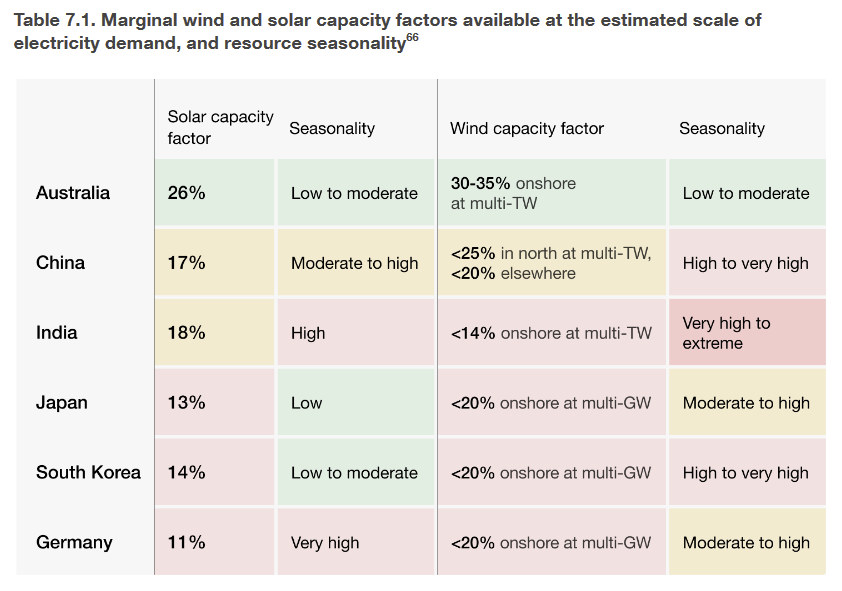

Making DRI is very energy intensive. In fact, to get the energy to produce all that iron and other goods discussed in the report – e.g. aluminium, silicon, ammonia, urea – the author estimates that we would need to build solar and wind farms that “span about 1.1 percent of Australia”.

The cost of constructing farms greater than the size of Tasmania, along with the grid to transport the electricity, who pays, and how will that affect the profitability of these projects?

Not discussed, although the author assures us in a footnote that they will be completely separate from the existing grid:

“Superpower projects on their own (very large) ‘microgrid’, separate from the main grid, may also avoid high Australian network costs. Network costs comprise around 40-50 percent of retail electricity prices, due to a highly dispersed population combined with regulatory failures.”

That’s a very important caveat to be buried in a footnote. Especially given that these superpower projects will be remote, which is one reason why Australia’s network costs are so high. As the federal government’s Department of Industry, Innovation and Science said in a 2016 factsheet:

“Australia’s size and low population density mean that we have the world’s largest integrated electricity network, which can be costly to operate, particularly in remote areas.

Other factors, like damage resulting from storms and bushfires, also affect overall network costs. As a result, network charges make up a much bigger proportion of electricity bills in Australia, compared to other countries.”

So, to become a green energy “superpower” Australia just needs to construct wind and solar panels all over the Pilbara, where it’s expensive to build anything because of the harsh cyclonic climate and lack of a local workforce. Essentially, the green energy “superpower” manufacturing revival would involve an even larger fly-in, fly-out workforce (we still need people to mine the ore, remember!), and assumes that the costs of doing all of that will be less than whatever energy savings we get from our comparative renewables advantage, as shown in this table:

Australia once had some of the world’s cheapest electricity, during which manufacturing withered away, at least as a share of the total economy (real output continued to increase), despite “a disproportionally high share of government assistance”. There are forces that prevent manufacturing from gaining a foothold as a share of the total economy in Australia, and energy costs are just one of many.

Another problem with this “superpower” plan is Australia isn’t the only country that obsesses about – glorifies – manufacturing. If you know anything about China, you will know that manufacturing is fundamental to the Communist Party; Xi Jinping goes as far as calling it the “real economy”, perhaps because of the Marxist reliance on the labour, rather than subjective, theory of value. He’s not just going to sit by while Australia displaces 3.2 million steel workers.

On that note, China also intends to become carbon neutral by 2060, without relying on reductions in countries like Australia. No new coal-based steelmaking plants have been permitted in 2024, with all new production coming via electric arc furnace projects, “which could signify a turning point for the Chinese steel industry in terms of halting new investments in coal-based steelmaking capacity”.

So even if DRI processing made sense in Australia, by the time we got past all the ancestral water serpents and dreaming stories about blue-banded bees, China will probably have decarbonised its steel industry and, because of its other comparative advantages, outbid Australian producers for Australian ore, given that shipping is only a small portion of the total cost.

However, despite the deeply flawed – perhaps naive – analysis, what I can get on board with are the report’s recommendations, which I will repeat here to save you the click (emphasis in the original):

- Address market failures by pricing CO2, supporting innovation and investing in transport and energy infrastructure.

- Allow market forces to guide the most cost-effective investments.

- Maintain open trade to secure Australia’s access to low-cost inputs and establish reliability as a source of critical materials.

- Manage debt and inflation to help restrain interest rates, which is essential for attracting necessary capital, including foreign investment.

- Accelerate green project approvals to stay competitive globally.

- Ensure policy certainty by building bipartisan support for reforms to provide investor confidence for long-term projects.

I think those are all basically good ideas worth exploring, even if they won’t make much of a difference in terms of a green manufacturing revival because of all the other constraints to manufacturing in Australia that I’ve previously discussed.

But I am sceptical in the government’s ability to correctly set a price for CO2, and in its ability to sell it politically: we have some very large, influential emitters of carbon in this country, and they’ll be disproportionately affected by a carbon tax. Some form of emissions trading scheme with a decent share of the initial credits going to those most affected is likely to have a better chance politically, even if a revenue-neutral carbon tax would be the most efficient way to internalise the costs of emissions.

Going back to the Gittins essay, he concludes by insinuating that the only thing necessary for an Australian manufacturing renaissance is for “the Labor government and the Coalition opposition… [to] extract the digit”.

I don’t know what Gittins means by that. If it’s what the report recommends, then it won’t make “certain classes of manufacturing part of our comparative advantage”, as he hopes. And if “removing the digit” is simply code for scaling up industrial policy with schemes like a Future Made in Australia, then most of us will be poorer because of it. A few industrialists will get wealthy, sure, but it truly is a race to the bottom; indeed, if those are his views then I’m surprised he didn’t suggest adopting a five-year plan to get us to superpowerdom.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!