Should Australia be the richest country in the world?

A week ago the founder of Freelancer, Matt Barrie, went on somewhat of a rant discussing the current state of Australia. Specifically, Barrie listed off a bunch of reasons why Australia should – but isn’t – “the richest country in the world”:

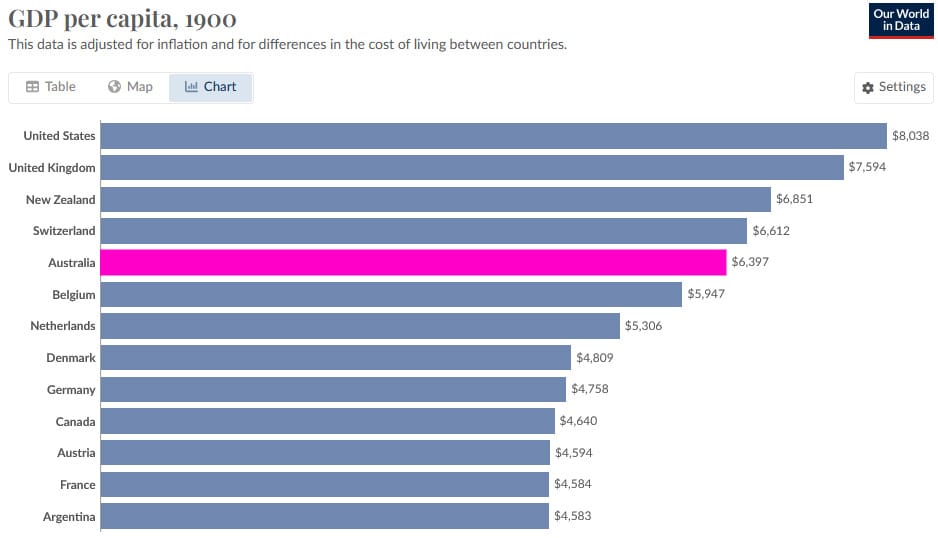

“We’re in a situation right now where we should be the richest country in the world, and we were the richest country in the world in 1900.”

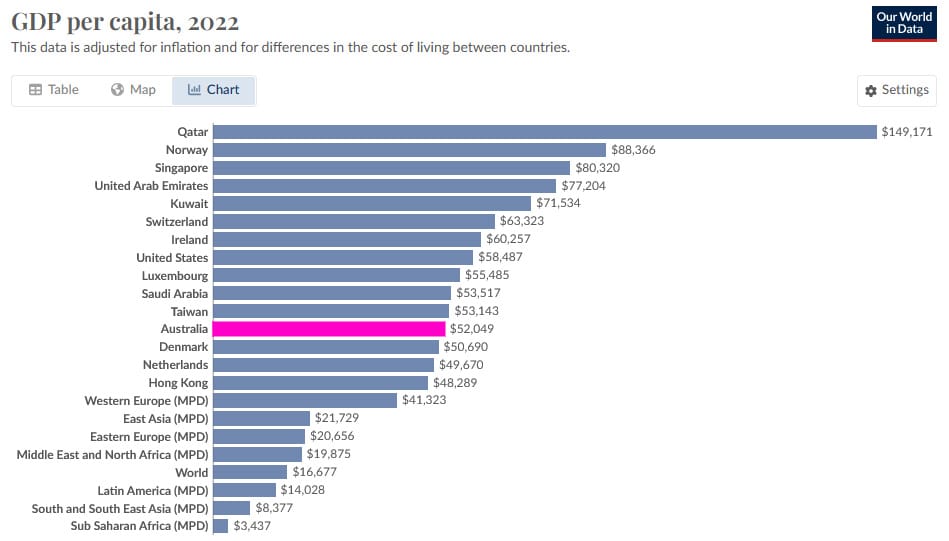

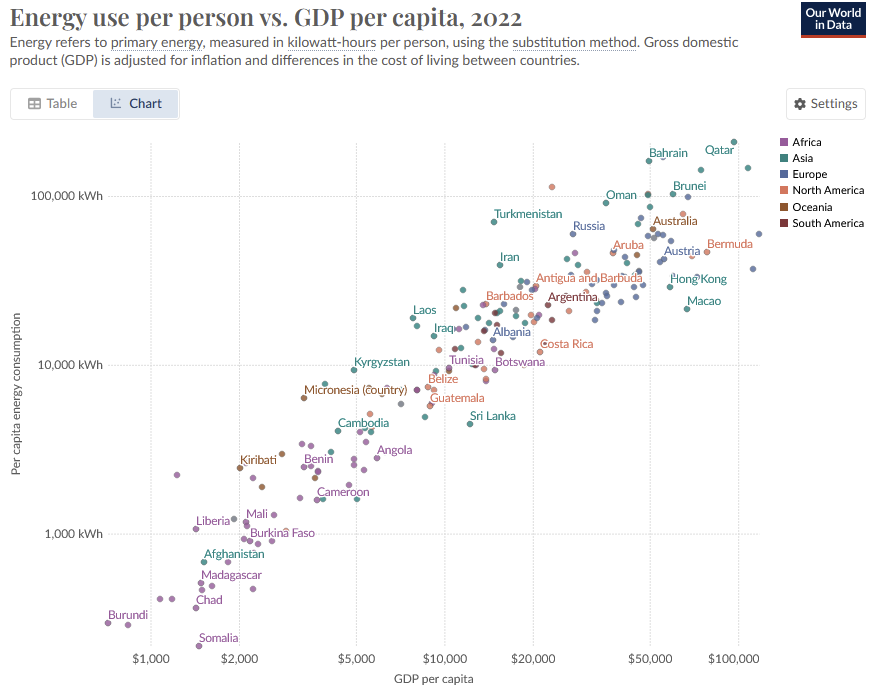

Before getting into Barrie’s long list of problems and proposed solutions (his rant was based on a blog post which, according to Medium, is a 72-minute read), I’ll just add that while Australia may not be the richest country in the world today, it’s pretty darn close:

If you remove the oil nations, tax havens and entrepôts, then Australia is only below the United States and Taiwan. Believe it or not, but that’s actually above where we were back in 1900, whether you’re looking at the size of the total economy (19th) or on a per-person basis (5th):

And if GDP isn’t your cup of tea, Australia is also right at the top of various standard of living indicators today, including education, health, civic engagement, and believe it or not, housing (many other places have it worse) – all pretty important things!

But that doesn’t mean we can’t do better. My issue is that while Barrie has correctly identified some areas in which we can certainly improve, his solutions would probably do more harm than good.

The housing theory of everything

Barrie kicks off his rant with housing, claiming that it has got to the point (in terms of affordability) where it’s bringing down society itself:

“It’s not a functional society anymore. You need people to be able to afford to buy housing and shelter in order to have a functional society. In Sydney now the median house price is about $1.8 million, which is mathematically impossible for the average person to buy the average house.

…

We have house pricing that is astronomically expensive — it doesn’t make any sense anywhere in the world. A terrace house in Woollahra is the same price as a cruise ship. The root cause of this is the cost of land, and the root cause of that is mass immigration. We have the most expensive casual wages in the world but it’s not enough to live on because people need somewhere to live.”

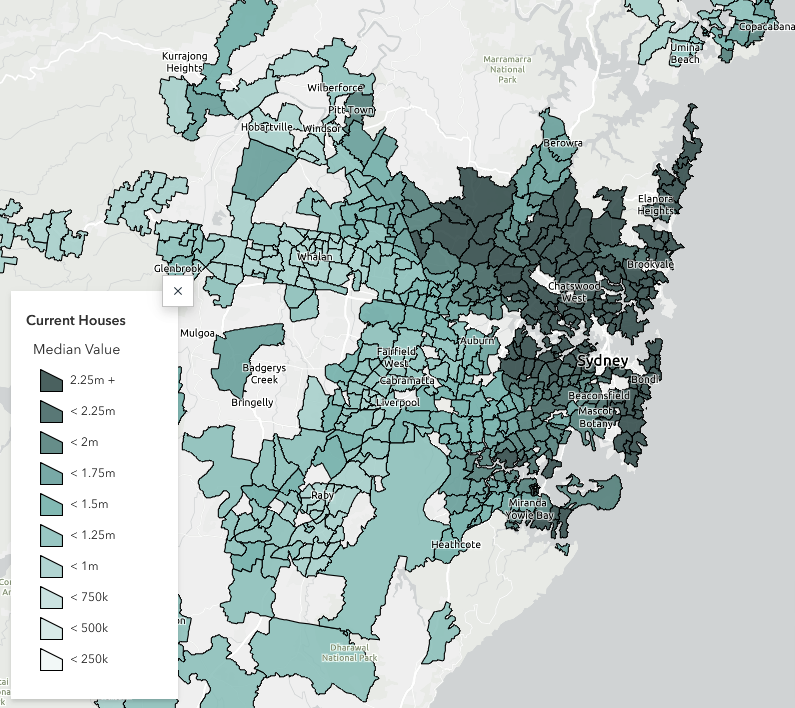

There’s a lot to unpack there. Barrie has a tendency to exaggerate, starting with his estimate of the median house price – the latest CoreLogic data has Sydney at around $1.45 million for a house, or $860,000 for a unit. It also varies drastically by location; out in Liverpool, about a 40-minute drive from the CBD, the median house value is $1.0 million, or $450,000 for a unit:

That doesn’t mean he’s wrong; Australia – but especially Sydney – has a housing affordability problem. But where he does make a mistake is blaming the problem on “mass immigration”, when the evidence suggests that they have a minimal, or even negative, impact on house prices.

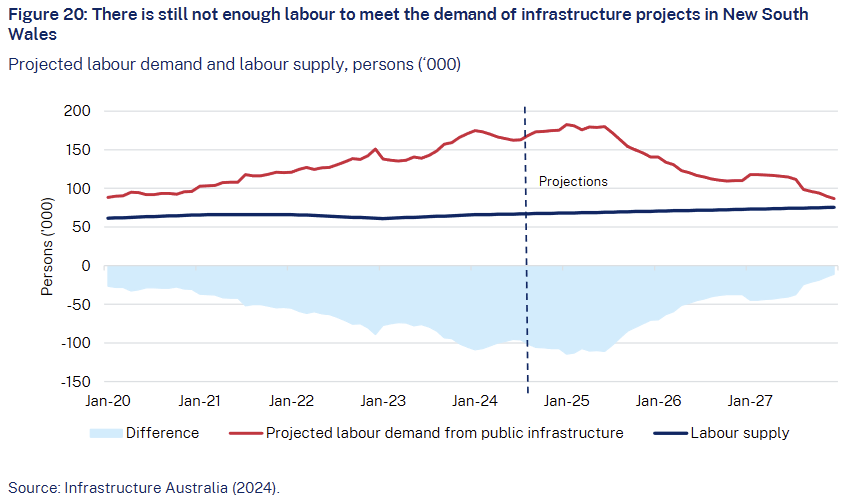

According to the NSW Productivity Commission, migrants can also be part of the solution if they have construction-related skills. Instead, the Commission (rightly) puts the blame for higher prices on elevated interest rates (caused by too much stimulus during the pandemic) and high construction costs (major state public infrastructure projects crowding out housing construction):

But the biggest culprit is land-use zoning:

“Zoning restrictions have unduly limited overall developable land supply, driving up land values in metropolitan New South Wales, including in greenfield sites.”

So, Barrie looks to have correctly identified a problem, but because he gets the causation wrong, his solution would either do nothing or make the situation worse.

The good ol’ days weren’t all that good

After a lot more on immigration, Barrie moves on to his dream, in which he wishes for policies that would take Australia back to the good ol’ days:

“For a while, Australia was a great place to live and we had manufacturing, for example, as a substantial portion of the GDP of this country. We made cars, we made a bunch of different things. We had whole supply chains for various things. And then we went into this path of just easy relentless growth where it was just house prices drifting up and shipping iron ore, coal, gas and gold overseas.

…

You would think that a country with 1200 years of coal supply would be an energy superpower. You would think a country with 28 per cent of the world’s uranium reserves would be an energy superpower. You would think a country with 20 per cent of the world’s gas exports would be an energy superpower

…

[We should be] an energy and electronic and mechanical engineering superpower. We control 56 per cent of the world’s iron ore exports. You would think that we would be a steel superpower. We have cheap energy, we have abundant iron ore, and we [should] elaborately transform that to become an export powerhouse. We should be the richest country in the world, full stop. We have everything.”

Barrie gets his facts right this time; manufacturing made up around 15% of GDP back in the mid-1970s, versus around 5% today, and we did make a bunch of things. We actually make even more “things” today – real manufacturing gross value added has grown by 65% since 1975 – but I’ll give Barrie a pass, because clearly he’s talking about relative shares.

But just because a country is endowed with natural resources doesn’t mean it should do everything. We only have a finite amount of labour and capital, and the concept of comparative advantage means that even if we were better at doing everything than other countries, it would still be in our (and their) interest to specialise and trade. As David Ricardo wrote:

“Though she [i.e., Portugal] could make the cloth with the labour of 90 men, she would import it from a country where it required the labour of 100 men to produce it, because it would be advantageous to her rather to employ her capital in the production of wine, for which she would obtain more cloth from England, than she could produce by diverting a portion of her capital from the cultivation of vines to the manufacture of cloth.”

Australia is really good at producing commodities like iron ore, coal and natural gas. If we forcibly diverted some of the scarce labour and capital working in those industries to other activities via taxes, tariffs, or subsidies, it would reduce the total amount of “things” that we’re able to produce or purchase.

We could physically produce cars in Australia again, but doing so would reduce the total number of cars – or other goods and services – available to us. And in a sense, the law of comparative advantage means that we still do manufacture cars in this country. It’s just rather than assembling them in a factory, we dig them out of the ground in the Pilbara.

Energy is the great enabler

Where I can agree with Barrie is on energy:

“So we have a cost-of-living crisis caused by input costs. We have an energy crisis through very poor energy policy where we’ll export all the raw materials to build renewable generators, which are energy negative on the energy that’s consumed to get the materials out of the ground, which ship back to us and are unreliable. As a result, we can’t run a reliable manufacturing industry in this country.”

It really is a great failing of this nation that our advantage of energy abundance is slowly fading away as our dilapidated coal mines are retired. Energy is the great enabler, and without it Australia will never be the wealthiest country in the world.

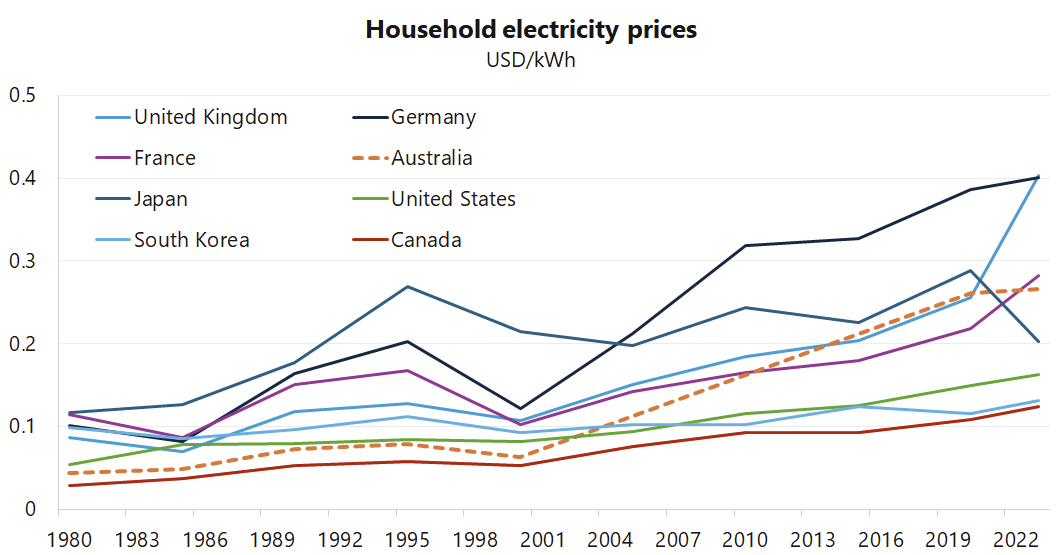

Going from having some of the cheapest power in the world between 1980 and 2000, to one of the most expensive today, is not good for Australia’s future prospects:

Put everything together, and Barrie concludes:

“Literally, this country is going to hell on a hand basket. We are 93rd in the Harvard Economic Complexity index in terms of the complexity of things that we produce, how sophisticated they are, and how much people can replicate them. Our economy in terms of sophistication and complexity is on par with Equatorial Guinea, where they don’t have a cinema in the entire country.”

A nation doesn’t need to be economically “complex” – i.e. diverse – to be rich. Indeed, Australia is proof of that. That doesn’t mean it’s not desirable; being diverse certainly helps mitigate against shocks, especially the geopolitical sort (just ask Russia).

But if that resilience comes at the expense of being rich today, then it’s not necessarily a path worth taking; the best decision may be to make hay while the sun shines and work to ensure that, in the event of a worst-case scenario, our institutions are able to support adaptation.

On that latter point, I’m concerned about the medium-term. Generations of Australian politicians have squandered our mineral wealth – and some, because they’ve racked up debt – and have become dependent on various taxes that make it difficult for Australian to build successful businesses outside of mining and banking.

But I’m also confident that if the situation were to become truly dire, our institutions would force a change relatively quickly.

Lessons from the Nobel Prize

Barrie suggests that changes to government policy can fix it all:

“It is all being caused by government policy, which can be turned around on a dime.”

On that I agree, although I would almost certainly have a wildly different list of preferred policies to Barrie, which gets to a problem: if a clearly very intelligent entrepreneur can’t grasp the economics behind Australia’s policy needs, what chance does the public have? If the median voter theorem is to be believed (and I tend to rate it highly), the answer is very little.

Which brings me to the next issue: Australia has passed welfare-enhancing reforms in the past, so why can’t it do so again?

The problem is that for meaningful reform to happen, the conditions need to be just right. At least that’s what this year’s winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, which went to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson earlier this week “for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity”, have found.

Their most famous work examined the colonial experience of several countries as a kind of natural experiment. Essentially, they wanted to know what caused Europeans to set up either inclusive (those that incentivise and facilitate investment in human and physical capital) or extractive institutions (those that discourage it).

What they concluded was that it depended on the environment early colonisers encountered. In already-prosperous places, or where mortality rates were high (e.g. because of malaria), colonisers tended to introduce or maintain extractive institutions; that is, institutions that facilitated exploitation such as local slave labour in mines and plantations, as well as any existing taxation schemes.

By contrast, in places with lower risk of mortality, small (e.g. Australia) or relatively agrarian (e.g. Canada) native populations, and large, sparsely settled land, long-term thinking kicked in and settlers demanded inclusive institutions. Those institutions included private property and common law, helping to facilitate early trade, commerce, industry, and – ultimately – wealth creation.

The problem is that even in countries with relatively inclusive institutions such as Australia, political elites may still block reforms that would raise prosperity because they can’t be sure that they’ll be compensated once they give up power. Similarly, an elite that promises welfare-enhancing reforms has an incentive to renege at a later point, so can’t be trusted with the power to make those reforms. In both cases there’s a commitment problem and so potential improvements don’t occur.

Most of the time, those constraints can be insurmountable. So, instead of reforms that would fix things like housing, we get half-hearted attempts that politicians hope will win votes (e.g. first home-buyer grants) but don’t disrupt the status quo all that much. But there are brief ‘windows of opportunity’ when the economic or political situation gets so dire that the forces blocking reform fracture, breaking up existing coalitions.

And that’s when significant reform tends to happen.

In the case of Australia, that’s most likely to happen when the golden geese lining the pockets of the elites stop laying eggs, or the share of revenue going to programs like the NDIS begin to threaten the nation’s fiscal solvency.

Until then, expect business as usual.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!