Should unions get special privileges?

The drama surrounding Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union (CFMEU) reached a fresh high last week when the federal government placed all of its branches into administration. The decision followed weeks of “allegations the union has engaged in bullying, corruption, and criminal infiltration”, and of course the resignation in July of John Setka after a media investigation accused him of serious misconduct (it seems investigative journalism is alive and well!).

A subsequent government investigation has struggled to get people to talk, due to “fear of reprisal”, and last Tuesday tens of thousands of union members marched in every capital city “in protest against the forced administration of the construction arm of the [CFMEU]”. According to an AFR report, there’s even a secret “leadership in exile” made up of the more extreme former members biding its time before it can reclaim control.

So, this doesn’t look like it’ll just blow over any time soon. It might get swept under the rug for a while – perhaps until the next federal election – but the ‘militant’ arm of the CFMEU still has considerable support. And as an economist, of course the whole saga got me thinking about the role of unions in Australia.

The economics of unions

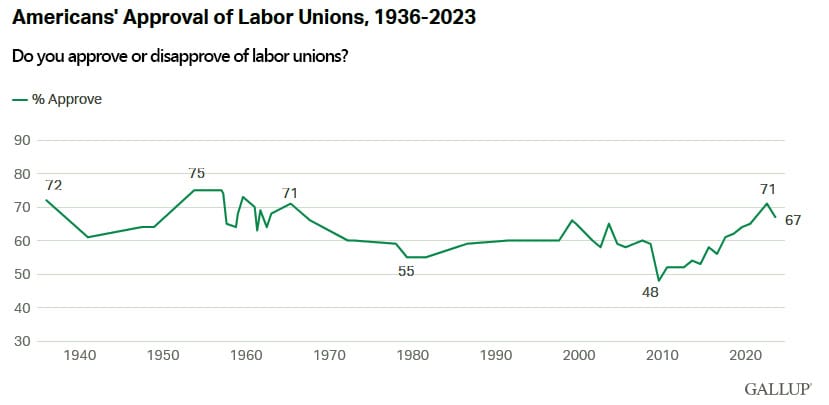

Unions sound like a good idea; who would object to groups of workers coming together to secure better pay and benefits? They’re popular with the public, with opinion polls frequently showing that people think favourably of unions, even if the majority is “not interested at all” in actually being a member of one.

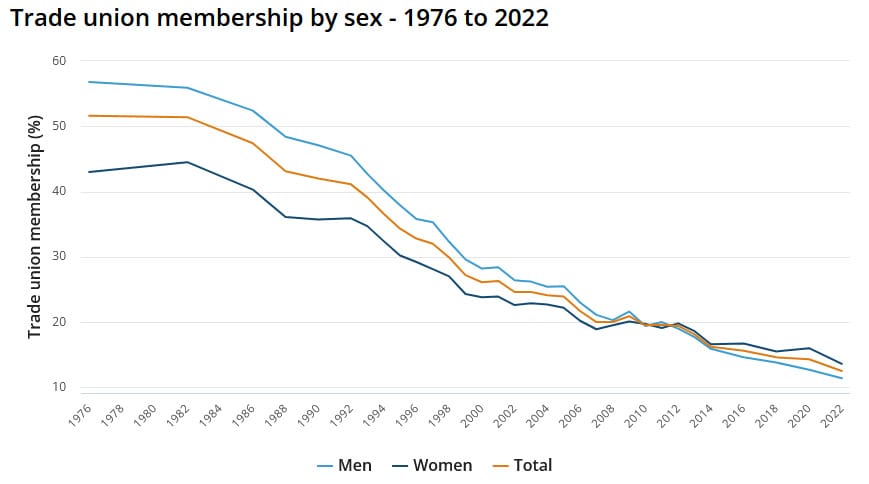

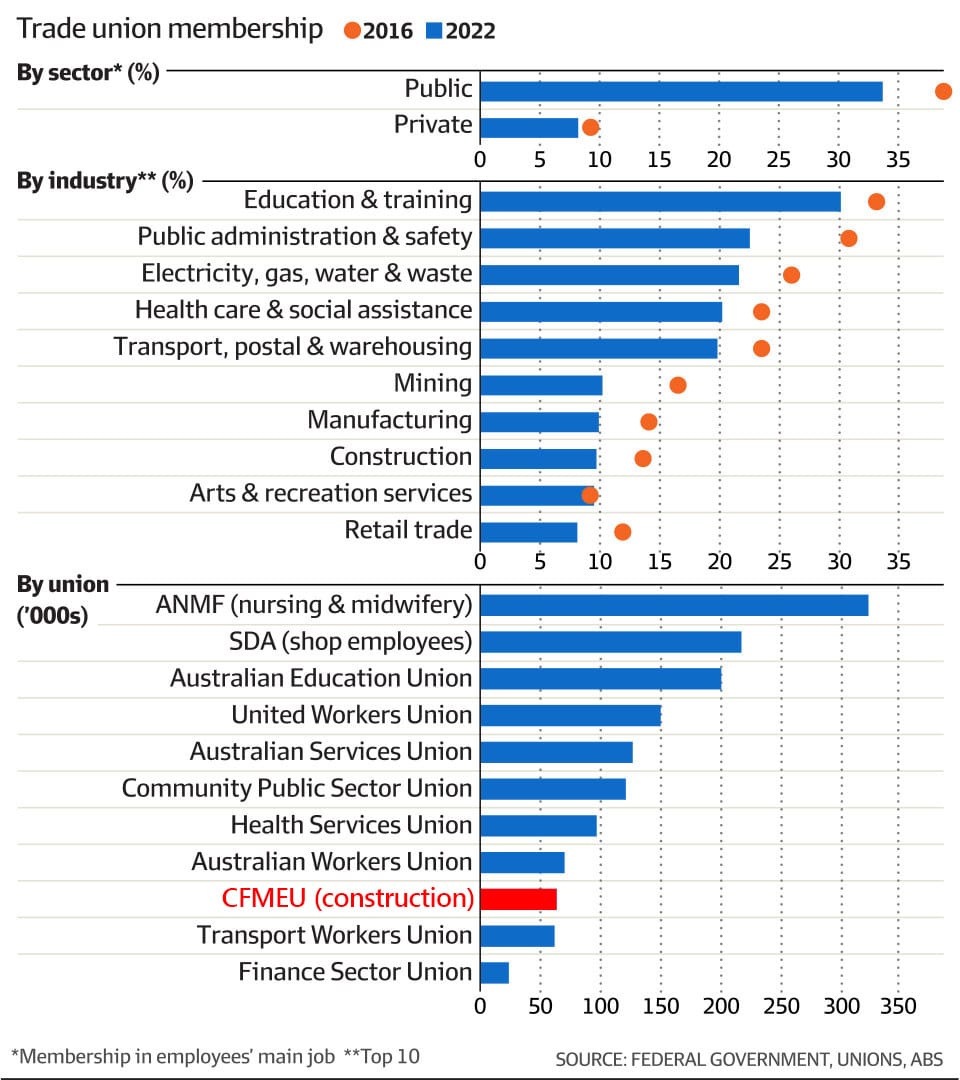

The above survey is from the US but the trend is similar in Australia, where only a small and declining minority of workers are members of a union:

However, not all unions operate in the public’s best interest, as evidenced by the recent controversies surrounding the CFMEU. Fundamentally, unions exist to benefit their members. As economist Walter Williams described, the public doesn’t fully appreciate that fact:

“A good part of the difficulty of understanding [labour] unions stems from the widespread practices of using the terms ‘union’ and ‘worker’ as if they were identical and shared identical interests. They are not identical and often have conflicting interests.”

Teacher unions aren’t student unions, transport unions aren’t consumer-advocate groups, and construction unions aren’t about constructing stuff. It’s why, after getting sacked for his role in the alleged corruption, former NSW CFMEU member Denis McNamara threatened to “organise and we’ll even manage to close this industry”.

That’s just not what someone who actually cared about our housing shortage, recurring infrastructure cost blow-outs, and workers would say.

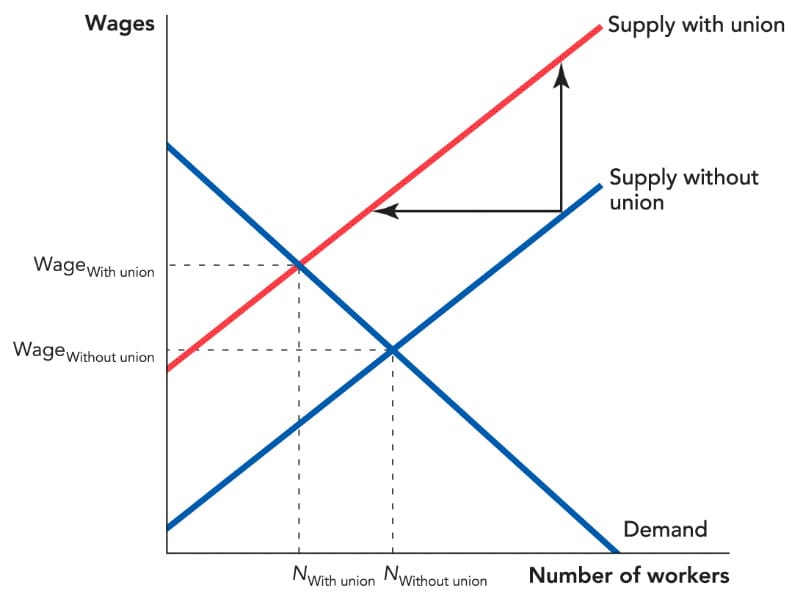

In economic terms, unions are effectively cartels for labour, which they use to raise wages above competitive levels for their members. They don’t hide this feature: plastered at the top of CFMEU Victoria’s join page is the statement, written in bold, that “members earn at least 20% more than non-union members on average”.

Economic theory is pretty clear about how they achieve that:

Unions get their power by legally limiting the supply of jobs, raising the price (wage) of those jobs. But they don’t raise average wages in the economy, because the workers who can’t find work in a restricted union industry join the rest of the labour force, increasing the supply of labour elsewhere, driving wages down. It’s why relatively low-union member countries like the United States, Switzerland and of course Australia still have wages as good, or better than, most of Western Europe, where union membership rates are much higher.

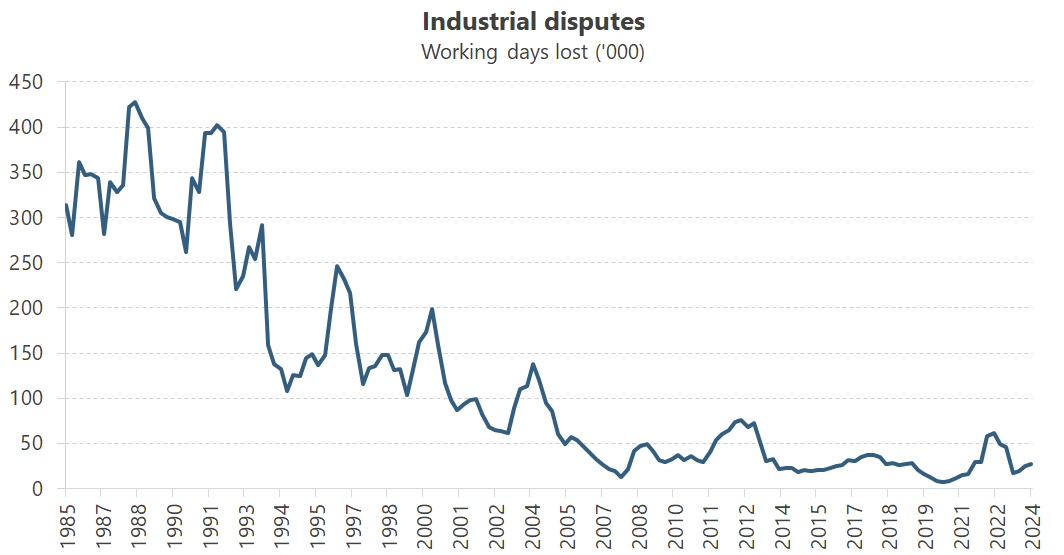

How do unions restrict supply? Through special privileges granted to them by the government. In Australia, those privileges aren’t anywhere near as strong as they once were: major reforms in the 1990s banned unions from forcing employers to hire only union members, effectively eliminating compulsory membership and their ability to be a true labour cartel.

Basically, the most destructive union practices were made more difficult to achieve. Post-reforms, unions were supposed to be limited to providing value for workers and employers without the large, economy-wide costs such as prolonged strikes that dominated the 70s and 80s:

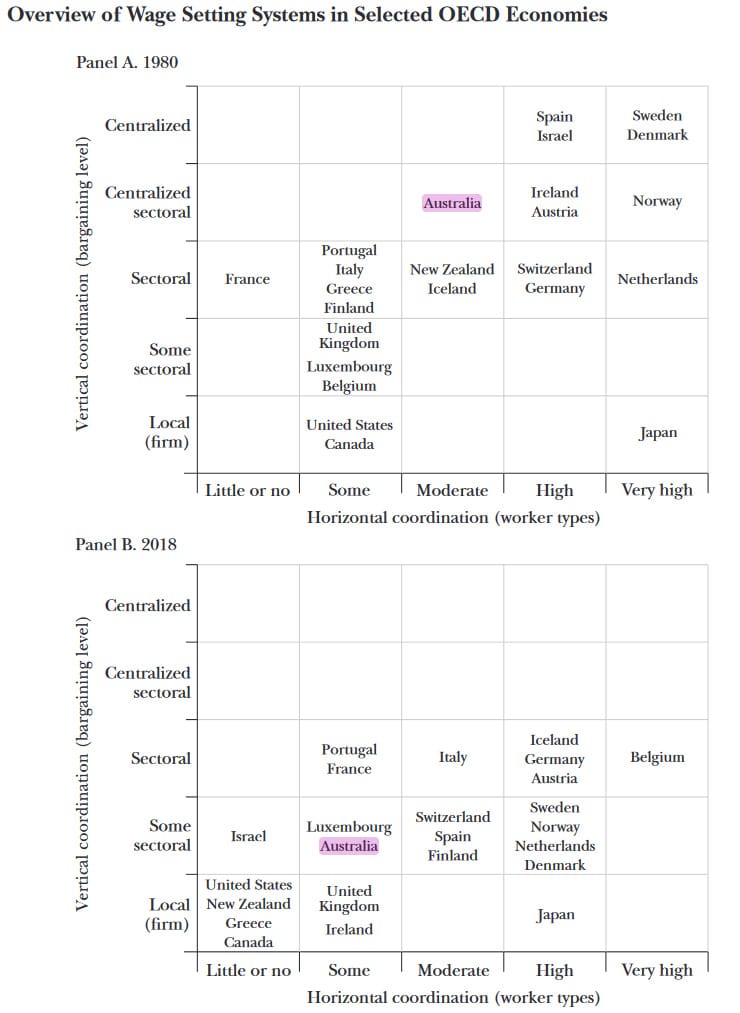

Reforms were also made to wage bargaining processes. As a result, Australia moved from having one of the more centralised systems in the 1980s to being more in-line with its OECD peers in 2018, giving workers and employers more freedom to ensure they’re properly matched with each other:

As a 2022 paper in the Journal of Economic Perspective from which the above chart was pulled said, “the fundamental change in how wages are set over the past few decades is a decentralisation of collective wage bargaining, not a shift away from collective to individual wage setting”.

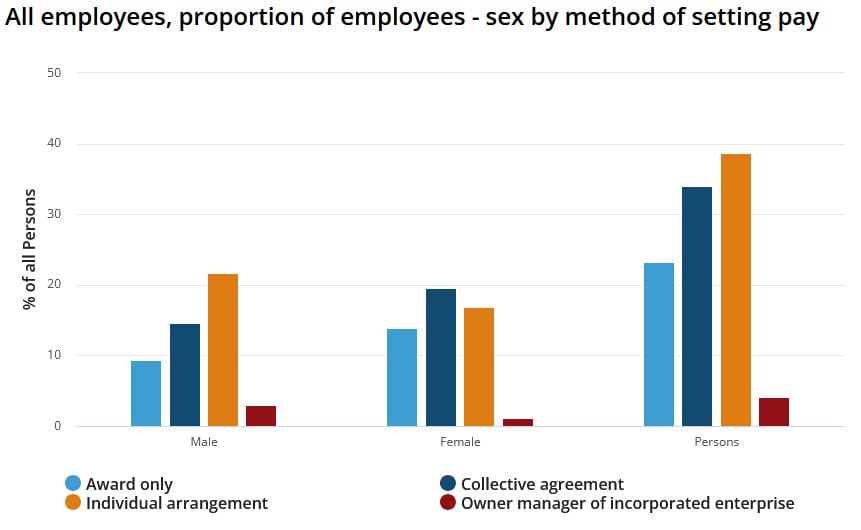

In Australia today, nearly 60% of workers still have their wages set by award or collective agreement, and unions are involved in those negotiations – just without as much power over the process as they had back in the 1980s when it was highly centralised:

Plenty of Australia’s unions are perfectly fine, likely providing social benefits that outweigh their costs. But because of the incentives involved, certain types of unions, such as the CFMEU, start behaving in an entirely different and socially destructive way.

When unions go bad

Unions as an institution have been incredibly durable, and as a society we probably want to keep them around to balance any power discrepancy between labour and management. For example, in industries that are relatively concentrated, i.e. dominated by a few big corporations, unions ensure that workers are paid properly. While increasing competition would be the first-best solution, sometimes that’s just not possible because of the nature of the industry (e.g. where there are large economies of scale).

But then there are other unions that exist purely to capture unearned rents for their members, in industries that aren’t very concentrated at all. These unions are mostly found in the public sector, but also in the private sector where a large portion of the work is allocated by the government.

A 2015 paper in the Journal of Politics found that public sector unions raise total compensation for their members by raising wages, but their biggest impact was in improving member benefits, which could be 15% to 25% higher than otherwise:

“[W]e find that collective bargaining and political activity both increase the amount spent on salaries and health benefits per capita: collective bargaining increases per capita salary expenditures by 4.4% and per capita health expenditures by 19%, and political activity increases salary expenditures by 10% and health benefits expenditures by 12%.”

In the public sector, the incentive for unions to restrict the level of employment isn’t as strong as it is in the private sector because there’s no profit motive. They’re also not negotiating with taxpayers but politicians, who are spending other people’s money and face policy time inconsistency: they can agree to deals today that will push some of the costs onto future politicians and taxpayers.

The economic incentive for unions to restrict labour supply in the public sector is entirely flipped, as a larger public sector – or even more workers on government projects – means more union fees and political power, which the union can use to “push for higher compensation (and other goals)”.

Basically, the employer of these union workers is the government, and with no profit ceiling to put an upper limit on benefits, the disemployment effect seen in private sector unions isn’t as obvious; for example, the authors found no effect for fire fighter employment levels, with only a small decline in police numbers relative to jurisdictions that don’t collectively bargain for those services.

We see that in Australia. Most union members are in the public sector (34% 0f workers), and those in the private sector tend to be in unions whose members do a lot of work for government, e.g. on relatively large infrastructure projects:

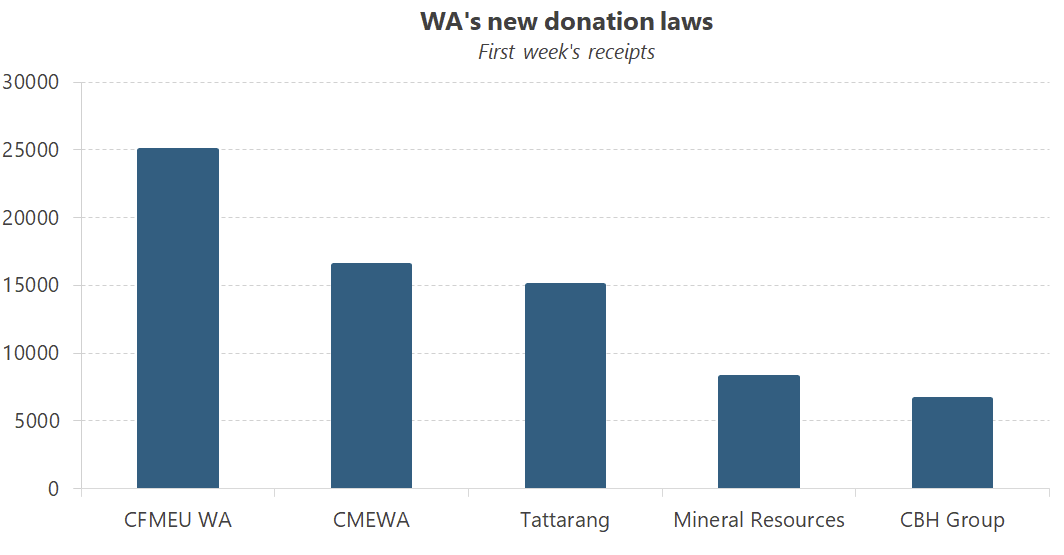

Unions are also among the top donors to politicians and are well organised relative to the people who pay their members’ salaries, the humble taxpayers:

Around a third of federal Labor members are former union workers, and the number rises to about half in the Senate. So what you have is former union workers (politicians) bargaining on behalf of taxpayers against their former colleagues. It’s a version of the revolving door problem combined with the concentrated benefits and dispersed costs problem. Economic costs and benefits morph into political costs and benefits, and the incentives towards efficiency are replaced with what is politically expedient.

Limiting the gravy train

So how does this all relate to the CFMEU? Well, it basically still operated as a labour cartel in the 1980s-style, maintaining enough political clout to ensure it was involved at every stage on major government construction projects. For example, in Victoria “companies needed an enterprise bargaining agreement (EBA) with the CFMEU to get access to Big Build projects, and that meant allegedly paying bribes to fixers to deliver CFMEU EBAs”.

Today, unions wield significant influence primarily when negotiating with government entities. They infiltrate politics to ensure that if a government wants to build, say, a new railway, the business that wins the tender must first consult the relevant union and that union then makes it very difficult to use anything other than union labour. It’s not technically illegal – in theory you can hire non-union workers – but in practice it’s a throwback to the closed shops of the 1970s and 80s.

The projects involved are often worth tens or hundreds of billions of dollars, so there’s plenty of cream to be skimmed:

“This was formalised soft corruption at the very least, with a key Labor donor and factional player elevated to formal status as an automatic partner for any company seeking to tender for major government projects. No wonder CFMEU officials thought Big Build projects were ’their projects’ and that ’they control the market’. Like an oligopolistic firm exploiting its market power to gouge customers, the CFMEU was exploiting its market power to enrich its executives — and threatening competitors who might undermine that power.”

The CFMEU’s power stems from government-granted privileges, including the ability to limit labour supply to its own members on specific projects. Without that, it would probably be much smaller, weaker and less problematic.

Personally, I think the only way to stop other unions from becoming as corrupt as the CFMEU is to limit the gravy train by cutting off their special privileges and enforce existing laws against violence and property damage. The tendering process should be as competitive as possible, and most certainly shouldn’t have any requirement to consult the relevant union. Former union workers who are now politicians should have to recuse themselves from making decisions about projects where that union might stand to benefit.

I know that’s not realistic given a third of the Labor party are former union workers and unions are one of their largest sources of donations ( quid-pro-quo), but something has to be done. If not, the whole country could end up like Victoria, which leads the nation in unemployment and is in the middle of a review to “eradicate the rotten culture exposed in parts of the Victorian construction sector”.

It means fighting political pressure from the likes of the Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union (AMWU), which doesn’t want Treasury involved in allocating Future Made in Australia funds because it has “historically favoured market-based solutions that are anathema to the coordinated efforts urgently needed to transition these regions and our economy”.

That’s going to be difficult, because the assistant minister for a Future Made in Australia is Senator Ayres, a former AMWU secretary. I’ll let you connect the dots on how that one plays out.

To sum up, the CFMEU’s recent controversies highlight the need for a balanced approach to union power in Australia. While unions can play a crucial role in protecting workers’ rights, their ability to influence government can lead to perverse and costly consequences, and they should be constrained accordingly.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!