Should we tax big gas projects more?

According to politicians such as Allegra Spender, David Pocock, and Monique Ryan, we’re “giving our futures away for free” and “we’re missing out on billions in tax income” because Australia’s gas giants don’t “pay their share”.

To be clear, in the statements above the “we” refers to the Australian government, not you and me. But they do raise an interesting question: do Australia’s large gas companies pay enough tax?

Yes and no.

If you hadn’t heard, economists are big on efficiency. There are multiple types of efficiency, but in the context of taxes it’s all about minimising the marginal excess burden (deadweight loss)—i.e., the costs of raising a dollar in revenue.

Some taxes, such as stamp duties, are highly inefficient: they impose a large burden on society for every dollar raised. Others, such as uniform consumption taxes, are relatively efficient: they raise money with minimal distortions on behaviour and economic activity.

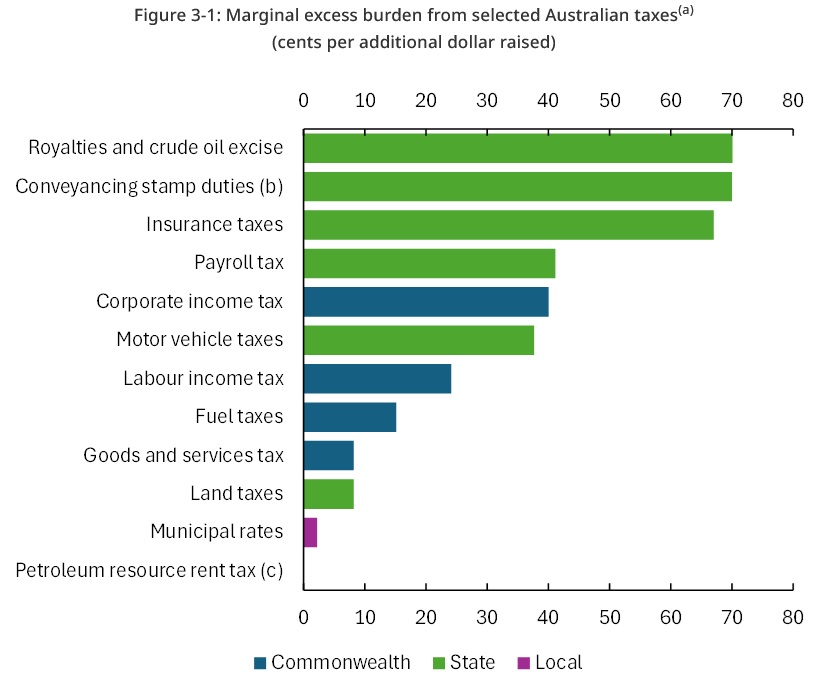

Here’s a helpful chart from the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), noting that its figures don’t account for the fact that Australian mining companies are largely foreign-owned, and so royalties are likely much less harmful than depicted:

Royalties and stamp duties are near the top because they effectively tax you regardless of whether you’re making money, which prevents beneficial exchange—whether by raising the hurdle rate for a worthwhile new mine, or making it costly to relocate for work. They persist because, constitutionally, Australian states have few alternative avenues from which to raise revenue.

This is all important because the more efficient your tax system, the fewer taxes you need to collect in the first place. Think of the tax system like a leaky bucket. If it’s highly inefficient, you need a large bucket (taxes) to account for all the spillage. If the tax system were better optimised for efficiency, you would be able to shrink the bucket, making everyone better off (or at least no worse off) for a given amount of tax revenue.

So, how does this all relate to ‘big gas’? Well, the federal Australian government already directly taxes offshore ‘big gas’ through the GST (efficient) and corporate income taxes (inefficient). On the latter, gas companies like Woodside are some of the top corporate taxpayers in Australia. As these firms are mostly foreign-owned, corporate tax actually works more efficiently than it usually does—the tax ‘sticks’, since foreign shareholders can’t claim franking credits.

There are other taxes on ‘big gas’, too. For example, the federal government indirectly taxes them through the income taxes its employees pay, and the states clip their fair share through payroll taxes, stamp duty on any houses purchased by resident workers, and so on.

But there’s also one tax unique to ‘big gas’, and it’s the one that all the politicians above are complaining about: the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax, or PRRT. It’s basically a super-profits tax that’s supposed to capture any windfall gains above what’s considered to be a ’normal return’ on a finite resource.

In economic textbooks, super-profit taxes are considered relatively efficient when implemented properly (see chart above). The problem with the PRRT is, well… it wasn’t well designed, with generous allowances for deductions and uplift rates that can be carried forward indefinitely, meaning many projects don’t pay it for decades—even when gas prices are sky high.

So, there’s a reasonable argument to be made that ‘big gas’ should be paying more tax through the PRRT, for example by time-limiting deductions, or reducing the generosity of uplift rates.

But the problem with changing the PRRT now is how late we are in the game: these firms and their mostly-foreign investors took big risks and fronted a lot of capital to get these projects going under a given set of tax rules. These gas projects were no sure things; just go and look at articles written a decade ago warning that Australia wasn’t competitive with the “United States, Canada, Mozambique, Tanzania and Russia”, and it’s fortunate that “most of the capacity has been locked up in long-term contracts of 15 to 25 years”.

The risk is if you change the rules on gas producers again—the Albanese government already tweaked the PRRT in its first term—you raise the perception of political uncertainty and sovereign risk.

That could mean the next time a mega-project comes along, whether in gas or some other industry, investors might feel some trepidation. Do we really want to lock up tens of billions of dollars in Australia, when the government might change the terms of the deal and expropriate our rents ex post (after the fact)? Sure, they say it’s just this one time… but how can we be sure?

I’m not making this up; there’s a decent body of work on regime uncertainty and the hold-up problem, both of which are anathema to investment. Basically, investors may raise their relative risk ratings for Australia, which then reduces the competitiveness of Australia as a destination for capital relative to other options (capital is highly mobile).

So, by all means tweak the PRRT and raise a bit more revenue from ‘big gas’. But the long-run damage it does to investment in Australia—remember, capital deepening is crucial for productivity growth—could cause much greater harm than the benefits any extra revenue brings us.

Sensible tax reform should weigh not just what we can get today, but also what it might cost us tomorrow.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!