Simply bananas

The Age’s senior economics correspondent, Shane Wright, recently penned a doozy of a column that demonstrated just how confused the world of monetary policy can get.

Citing a recent Bank of England working paper, Wright suggested that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) should forget about looking at the overall change in the 11 major groups that make up the Consumer Price Index (CPI), and focus more heavily on a single group – food and non-alcoholic beverages – because that’s what people care most about:

“In layman’s terms, if central bankers took account of inflation as it’s felt by ordinary punters, rather than creating artificial measures of underlying inflation, they’d have a much better idea of the price pressures across the economy.

…

Perhaps central bankers should take a leaf out of the book of politicians, who understand retail inflation particularly well.

Just look at the debate about supermarkets, where the Coalition has been agitating about prices for months, with even pro-business Liberals backing a ’last-resort’ policy of breaking up the supermarket giants caught in price-gouging, and the government has poured money into the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission so that it can better target supermarkets.”

I know Wright is just doing his best at interpreting a Bank of England working paper. But monetary policy is hard enough without journalists confusing people by leading them to believe that inflation can be better controlled if only the RBA would pay more attention to the things that politicians tend to focus on, like food prices, instead of a diverse basket of goods and services.

Relative price changes are not inflation

The RBA defines inflation as:

“…an increase in the level of prices of the goods and services that households buy. It is measured as the rate of change of those prices.”

Notice the use of the word “level”. In a market economy like Australia, prices are constantly in flux and frequently change relative to other prices in response to supply and demand. These relative price changes are not inflation, because barring measurement issues and ‘stickiness’, the level of prices would be unchanged: there’s still the same amount of dollars chasing the same amount of goods and services.

A good example of understanding that process comes from Wright himself, who quoted former RBA governor Ian Macfarlane’s decision not to tighten monetary policy when Cyclone Larry wiped out Queensland’s banana crop. Instead of reacting to the change in the relative price of bananas, Macfarlane ’looked past’ the temporary event and ignored the higher prices: it was clearly the cyclone that caused banana prices to rise, not excessively easy monetary policy, and so the risk of an inflationary outbreak was non-existent.

However, despite correctly recalling that event and the RBA’s apt response, Wright promptly forgets his own lesson and claims that the Bank of England’s research implies that “perhaps Macfarlane should have been worried after all”.

The problem is, that’s not even close to what the paper said. Here’s the relevant quote:

“In sum, we model a food price shock as a cost-push shock, which households perceive to be more persistent than it actually is. Based on this, we derive two simple but noteworthy results. First, the effect of a food price shock on inflation is larger than that of other cost-push shocks. Second, a central bank would have to respond more strongly to inflation to deliver the same inflation profile when faced with a food price shock compared to another similarly-sized cost-push shock.”

I have issues with the paper – e.g. it relies on the completely discredited idea of “cost-push” inflation – but even ignoring that, it was all about expectations.

When food prices are rising quickly during a time of general inflation – rising food prices are a symptom, not cause, of inflation – the Bank of England’s research says that the central bank should tighten monetary policy more aggressively to control that inflation. That’s because when inflation manifests in food prices faster than other prices, people will notice and their expectations of future inflation will rise more quickly, altering their behaviour and influencing the path of inflation itself.

What the research does not say is anything about what happens to expectations when a cyclone wipes out Australia’s banana plantations, is covered thoroughly by the media, and is acknowledged by the RBA. In other words, exactly what happened with Cyclone Larry in 2006, which “remains the only time a Reserve Bank governor has discussed bananas, inflation and interest rates in the same sentence”.

Macfarlane needn’t have worried! In fact, adjusting monetary policy to a relative price change caused by a temporary supply shock such as a cyclone would have been the wrong thing to do. Yes, there might be a one-off increase in CPI because the same amount of money is now chasing fewer goods. But that’s not inflation, which is persistent and stems from more new money chasing the existing (or lower) quantity of goods and services.

The Bank of England research was also careful not to tell central banks to weight food prices as much as politicians do, given how prone they are to confusing relative pricing with inflation. It simply recommended they not exclude food prices from their analysis:

“This suggests that it may not be advisable to focus primarily on measures of core inflation, which exclude food and energy prices… Disregarding food prices might lead them to underestimate the persistence of inflation expectations and, consequently, of inflation itself.”

If anything, the Bank of England is telling central banks to consider a broader array of prices than many currently do; in other words, the opposite of Wright’s interpretation.

Wright ends his column by following his own advice, hinting that the RBA should be looking to cut rates, because food prices have come down by more than overall prices:

“The most recent quarterly measure of inflation had overall prices up by 3.8 per cent and underlying inflation up by 3.9 per cent. But in the supermarket aisles, inflation was much lower at 3.3 per cent, and would have been even lower if not for a weather-related spike in the prices of apples and watermelons.

If the Bank of England researchers are right, the RBA would do well to be more focused on what people are doing in response to those high-priced apples and melons. God forbid what it should do if we lose another banana crop.”

Food is getting cheaper relative to other goods and services, half of which are still rising by more than 5% annually. But food prices alone tell us nothing about inflation.

So, to answer Wright’s worry about what would happen if we lose another banana crop, the only risk – other than the temporary lack of delicious bananas! – would be if the RBA had someone like Wright on its board who wanted to react to respond preventing the pass through to higher consumer prices. Doing so would be an unnecessary monetary tightening, strangling the rest of the economy and reducing overall welfare in the process.

The RBA’s gambit

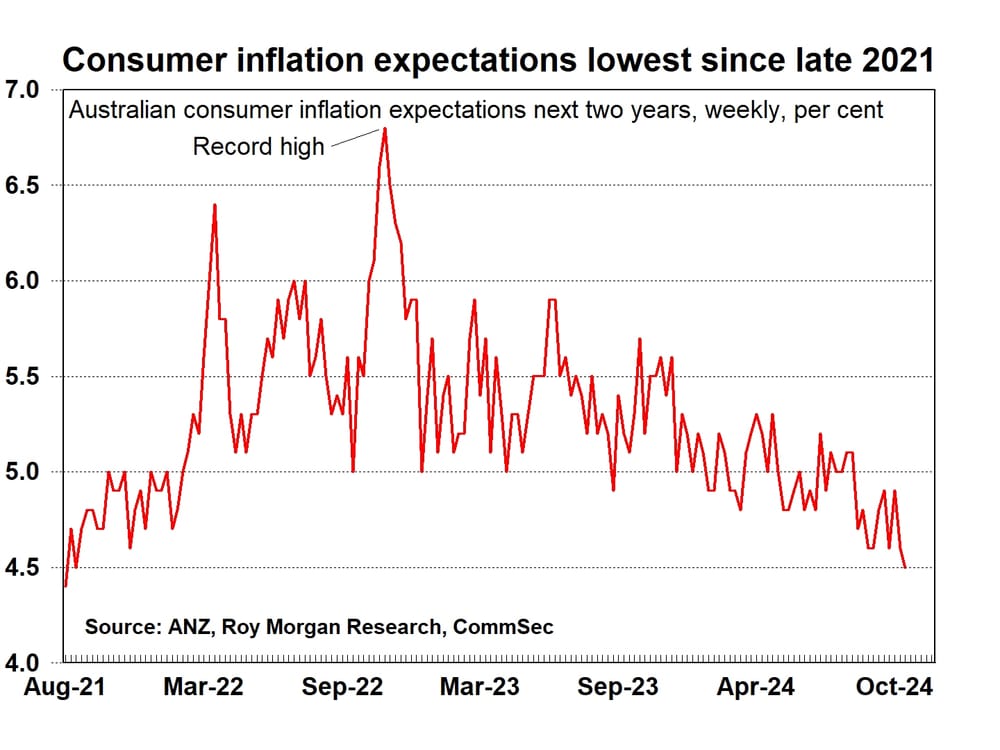

As for the present day, if the Bank of England researchers are right then lower food price growth in Australia should help moderate inflation expectations faster than otherwise, effectively tightening monetary policy (because of the Fisher equation’s link between nominal rates and expected inflation).

And the signs are good that’s what’s happening:

However, if the RBA was already holding nominal interest rates below real interest rates – and there are good reasons to think that it has been – then it could still take a long time for falling inflation expectations to get us to a point where the RBA is comfortable enough to start easing.

Contra Wright, the RBA will be looking at the price level, not a single expenditure class, when trying to measure inflation and set monetary policy. If anything, it will be even more likely to look through ‘volatile’ items like food and government-manipulated energy prices at this stage in the cycle, because of its past decisions not to tighten as much as it should have. The last thing the RBA would want in the midst of an inflation-busting credibility problem is to lose even more credibility.

The RBA’s deputy governor, Andrew Hauser, took part in a “Fireside Chat and Q&A” on Monday. During his speech, Hauser remarked that:

“It was a deliberate choice for us to not to tighten as much to protect employment gains, with a recognition that not tightening as much that inflation would take longer to come back and that rates would not fall as much or as early as it has in other countries.”

What’s peculiar about that strategy is the historical evidence suggests that “aiming for a hot labour market (which could reflect either an ambitious employment goal or a reluctance to tighten in response to overshoots of a more moderate goal) has often been associated with important macroeconomic problems”.

Additionally, a recent report by the International Monetary Fund found that the post-pandemic inflation presented central banks with a rare “favourable tradeoff”, whereby “widespread supply bottlenecks” caused by surging demand created an environment in which “policy tightening can be particularly effective at rapidly bringing down inflation with limited output costs”.

By instead deciding to navigate the “narrow path” to getting inflation down while also preserving employment gains, the RBA may have missed that tradeoff, harmed its own credibility, and risked spawning a litany of macroeconomic problems that can come from persistent inflation, such as newspaper economics correspondents pontificating about how “central bankers should take a leaf out of the book of politicians”.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!