Striking a balance on immigration

The latest thing™ in the US, at least for the first few weeks of the year – when the chaos that is Trump 2.0 begins, who knows what might happen – has been immigration. Specifically, the social media war being waged between 2016 anti-immigration MAGA conservatives and the 2024 version, which counts among its members many Silicon Valley techies (some of whom were migrants themselves).

And I mean war. For example, here’s a response by Elon Musk to someone telling him it was foolish to “optimise H1B” because it “shouldn’t exist” at all:

For those not familiar with the US immigration system (why would you be!), H-1B is a visa class that firms can use to hire foreign workers “to perform services in a specialty occupation”. In 2024 there were nearly 800,000 applications for the 65,000 annual spots (plus another 20,000 for those with advanced degrees), with the successful applicants selected via a lottery.

Still, into a US labour force of around 170 million it’s a drop in the bucket – around a 0.05% increase each year. But that hasn’t stopped the usual suspects from claiming that H-1B visa holders are taking ’er jobs and undercutting local wages:

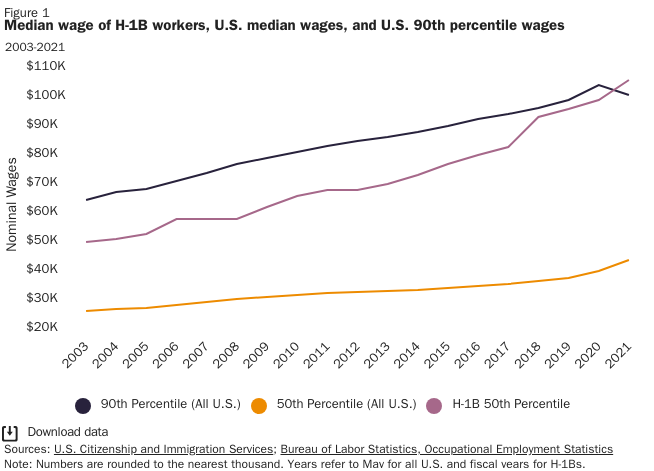

Bernie is, of course, wrong on all counts. H-1B visa recipients are required to be paid at least the prevailing wage for their job and location, and the data show that they tend to earn more than local workers.

They’re also younger than their American counterparts, meaning they’ll likely provide a positive fiscal boost during their stay in the US (potentially a lifetime). To the extent that they also create demand through their consumption, they’ll generate jobs for other Americans:

“Think of technology firms that need both engineers and janitors. When the supply of engineers rises, the demand for janitors increases, leading to higher janitor wages.”

A similar effect will occur if they boost productivity through their highly specialised skills, helping to raise real wages for all workers.

Finally, they’re also not “indentured servants”; all H-1B visa holders are free to move to a different company, provided they agree to take on your visa sponsorship. Or they could simply go back to their country of citizenship – it’s not like they wouldn’t be able to afford a flight home on their six-figure US dollar income!

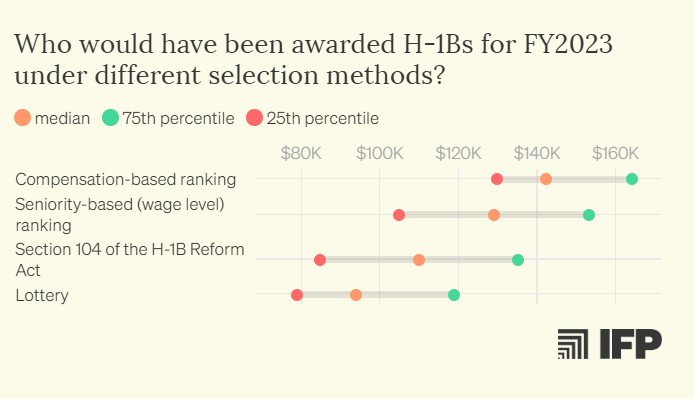

But none of that means the H-1B visa is anything close to optimal. For one, it’s a quota system ( always the wrong option) that allocates positions not on merit but luck; that’s no way to conduct economic policy! Simply changing the H-1B visa from a lottery to one which allocates places based on salary offers could add up to 88% more to GDP than the current system.

In fact, the lottery system is the worst possible of all the competing models:

If anything, the H-1B visa should be expanded, the fee increased, and the US will be laughing all the way to the bank as they brain drain other countries of their best and brightest. And there are signs that Trump might do just that:

Given that Australia is one of the many alternatives competing for such talent, I think there are lessons we can learn from all of this, especially in the context of the recent push-back against immigration Down Under over the past year.

Australians are turning against immigration

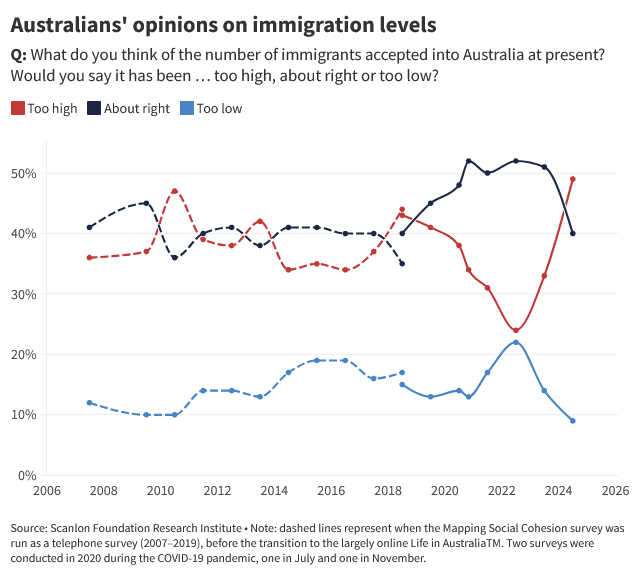

Australia has a long and successful history with immigration. But over the past two years, the post-pandemic surge in migration has awoken people’s inner xenophobia in ways that I think might be harmful for Australia’s longer-term prospects. For example, a survey taken late in 2024 found that close to a majority of people now thought Australia was now taking in too many migrants:

I think there’s somewhat of a perfect storm that has built up against migrants around the world, where the policy mistakes of the past (e.g. zoning laws) combined with media attention of the post-pandemic catch-up growth in migration – which “reactivates pre-existing prejudices” – has caused people to demand a policy response, even if it’s a bad one.

For example, a lot of Australians simultaneously hold the (correct) view that housing is too expensive, but also that our cities are museums that should be preserved from development, which raises housing prices. If that’s you, then committing yourself to poor immigration policy also makes sense – if we just stop growth, then we’ll have enough housing for everyone!

Such views are also popular politically. I’m reminded of Adlai Stevenson, who after giving a sensible speech while running for US President had the following exchange:

“Someone heard Stevenson’s impressive speech and said, ‘Every thinking person in America will be voting for you.’ Stevenson replied, ‘I’m afraid that won’t do—I need a majority.”

Somewhat ironically, the same people who frequently lament Australia’s per capita recession also tend to put the blame for it on migration. But without that migration – which raises real GDP (output) due to the added labour supply and education exports, and therefore likely lowers inflation for a given monetary stance – Australia may have been in a much worse, stagflationary recession by now. The average Australian would likely be worse off, even if conditions might have appeared to be better in the data.

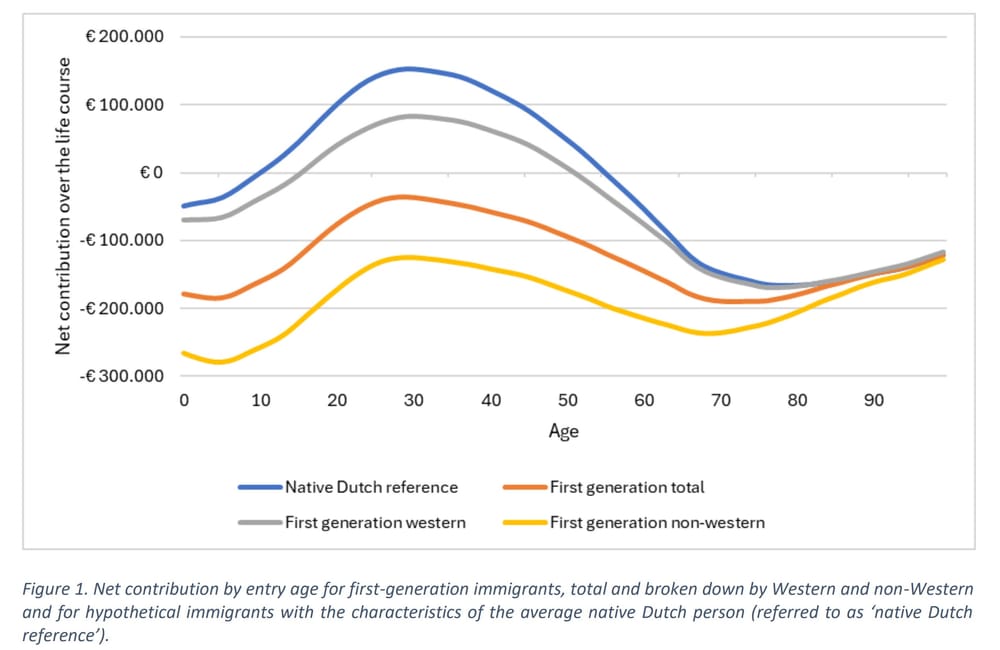

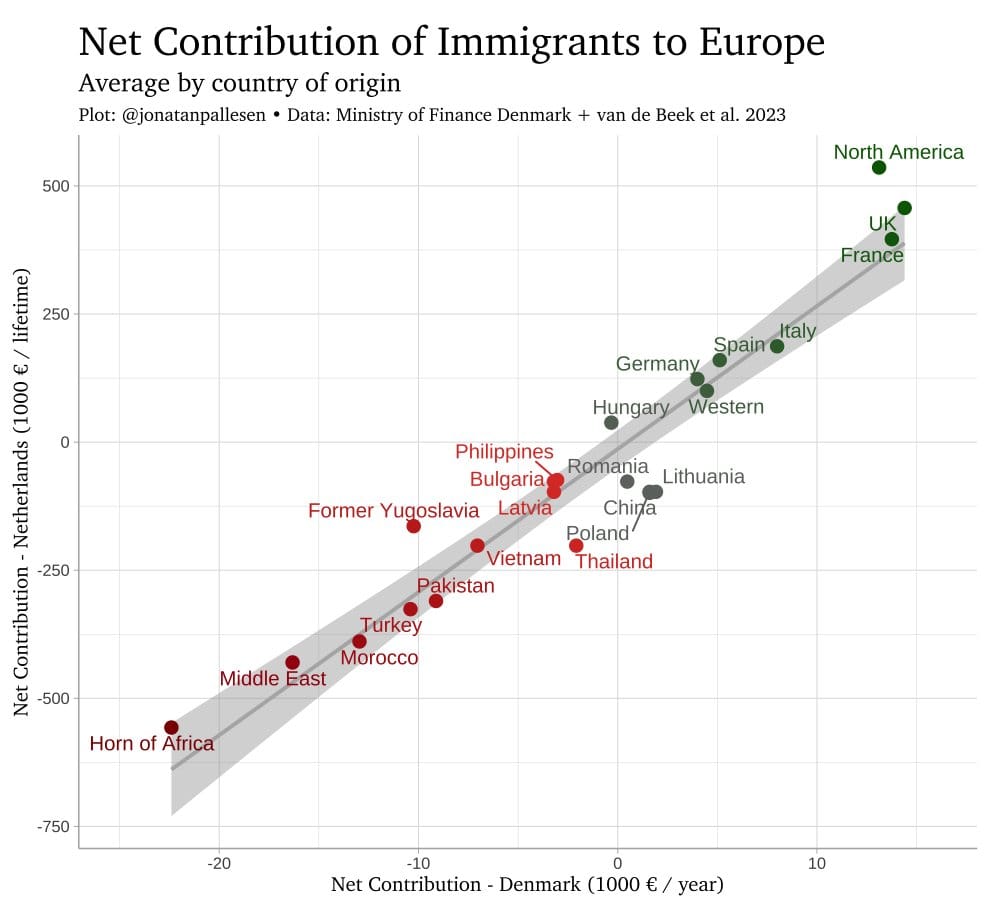

Now, there are legitimate concerns that Australia has started to let in too many ’low quality’ migrants in recent years, such as those lacking in transferable skills, possessing poor English language abilities, or flaunting questionable qualifications from overseas degree mills. And recently released data from the Netherlands has shown that the wrong type of immigration can be detrimental for the host country:

“Focus on the blue line for natives. People are net negative while they are young before they work, and net negative after they stop working. Children cost some money and produce nothing, retirees cost a lot of money (in pensions and healthcare) and produce little. Working age people produce a lot and cost little. The entire point of having useful immigrants is having people whose net contribution curve is pushed upwards such that the lifetime value is as positive as possible. As can be seen here, no matter at which age and where immigrants come from outside of the west, broadly speaking, they are net negative across the line span, as the Dutch natives are approximately net neutral. (I note that their models must be somewhat off because age 10 is when natives become net positive, but that’s impossible, it cannot be earlier than 20, and more realistically 25-30.)”

Basically, your first-best immigration policy should target skilled migrants from English-speaking countries. The data are pretty clear:

Migration benefits both countries, “because it sorts inventors to where they produce more innovations and knowledge spillovers”. As just one example, if Elon Musk was still in Africa would Africans still be able to enjoy Starlink internet at prices below what their state monopoly charges?

Now, Australia isn’t exactly a hub of innovation like the US. So a next-best policy – which Australia has used successfully for many decades – might be to recruit a lot of foreign students, have them pay to be educated, and provide pathways for those who obtain useful skills and who want to assimilate to stay in Australia.

Optimising immigration to Australia

It shouldn’t be difficult to have a well-functioning plan for immigration. I’ve written before about the Albanese government’s misguided attempt to ‘fix’ the student influx with quotas, and what it should have done instead:

“Higher fees will do the job without a quota. Done properly, they can render a quota useless: all you have to do is set the fee high enough to reduce demand to whatever you consider ‘appropriate’, and the number of applications will fall to that level. The government then collects a bit of extra revenue it can use to offset some of what the public perceives to be the worst consequences of international students, which mostly seems to be housing-related, and we can all get on with our lives.”

As for other visas, scrap the vast majority of them. Uncap the Employer Nomination Scheme, remove all “Core Skills Occupation List” requirements, reduce the age limit from 45 to 35, and set the salary requirement at something like 25% above the median wage for the job and location.

For family and other non-work visas, require them to have a sponsor that is financially responsible for them for several years – perhaps even through the payment of a bond that’s slowly returned – to mitigate some of the potential fiscal burdens I quoted above.

That’s it. The government can then periodically review the student visa fee to ensure that the intake aligns with what our universities and related infrastructure can handle, and Australia gets an unlimited supply of young, skilled migrants who want to assimilate. Employers can bring in above-average skilled workers, and families can be reunited – provided the rest of Australia doesn’t have to shoulder the fiscal burden.

The alternative to a sensible immigration policy is an endless stream of growth-destroying, supply-side restrictions dressed up as “solutions”. Such policy responses, which will inevitably be demanded by the electorate, boost short-term outcomes for various groups but make everyone poorer in the long-run.

We should all want Australia to brain drain the rest of the world. That means ensuring that Australia is an attractive place for talented students and highly skilled migrants, and one way to do that is by making it easier for the best and brightest to move here, while automatically weeding out any bad apples through the use of prices rather than quotas, queues, or lotteries.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!