Super Rugby's travel tax

How much does the tyranny of distance affect sporting teams? That’s not a question I’d usually discuss here at Aussienomics, but it is one that I’ve grappled with over the past couple of weeks as I’ve watched my local rugby team, the Western Force, sink to what looks to be yet another losing season. Twenty years after its inauguration, the club has yet to make a finals appearance in a league that now only has 11 teams (excluding the 2021 Covid-disrupted season when other countries weren’t involved).

There are plenty of possible reasons for that lack of success. Poor management, sub-par coaching, competition from other sporting codes, and the lack of grassroots rugby depth from which to draw players have all inevitably contributed to the club’s struggles.

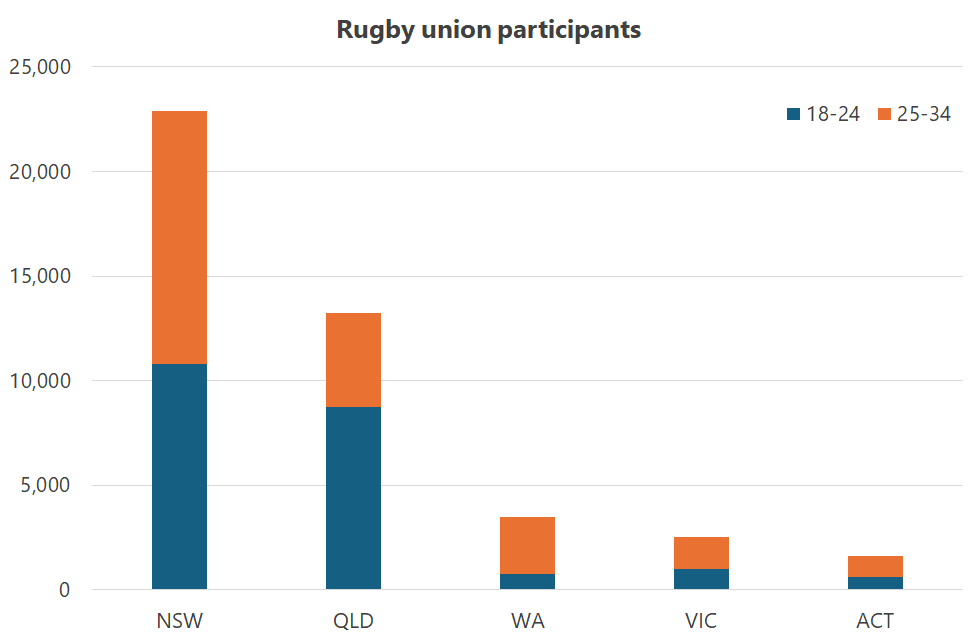

On the latter point, Super Rugby Pacific is a salary-capped league, so if you’re not based in a city with a large pool of local players you’re at a disadvantage from the get-go: you must pay a premium—perhaps up to 10-20%—to convince a player to uproot themselves and move across the country away from their family and friends.

In the context of rugby in Australia and its hard salary cap, that puts New South Wales and Queensland at a distinct advantage (the Australian Capital Territory isn’t as hard-done by as the data suggest, because it’s only a short flight or 3-hour drive from Sydney):

The fix for that discrepancy is relatively simple: invest in grassroots rugby and provide salary cap dispensation to offset WA’s recruitment disadvantage until it catches up. That was a model used by the AFL for many years in Sydney, which was in addition to four clubs (Gold Coast, Brisbane, Sydney, and GWS) being able to claim any of their own academy players that were drafted in the top 40.

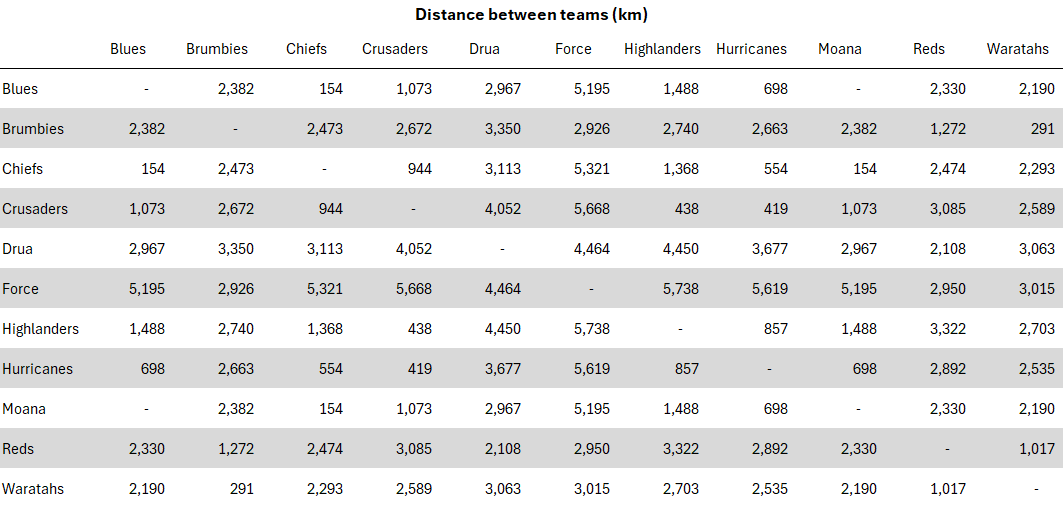

But there’s another big reason why the Western Force have struggled: travel. Perth is around 3,000km away from Sydney and Brisbane, and nearly 6,000km (a minimum of two flights) away from Christchurch and Dunedin in the south of New Zealand. Getting to Fiji to play the Drua is just as challenging, requiring two flights and nearly 5,000km in distance. Add time zone changes into the mix along with big rugby bodies on the narrow-bodied A330/737 aircraft that dominate the skies in Australia/New Zealand and it must be tough on players.

Indeed, there’s evidence that long-distance travel is a significant disadvantage for sporting teams. For example, Bernerth, Maurer, and Taylor concluded that travel “negatively impacts team task performance and team concentration level” of American NFL and NBA players. Bishop discovered that crossing two timezones negatively affected the team performance of Australian netball players. Duffield, Fowler, and Vaile found that longer, international flights make sleep quality and quantity significantly worse than domestic flights, and “test performance was significantly reduced”. Fowler et al also found that long-haul eastbound travel—i.e., the direction the Western Force travel for every away game—“has a greater detrimental effect on sleep, subjective jet-lag, fatigue and motivation”, especially within the first 72 hours.

Anecdotally, anyone who has flown regularly knows the toll that flying—especially across multiple timezones—can take on your body. ACT Brumbies coach Stephen Larkham said as much last week:

“Every year we travel over to Perth to play against the Force and we’ve slipped up in the last couple of years. It is challenging for us to get over there, to get acclimatised to the time zone.”

Now, some of that is unavoidable: you can’t just move the Western Force out of Perth. But what you can do is design the fixtures so that the burden is shared more evenly across the league as a whole. Unfortunately for Force tragics like myself, that doesn’t appear to be what the Super Rugby Pacific commission has done.

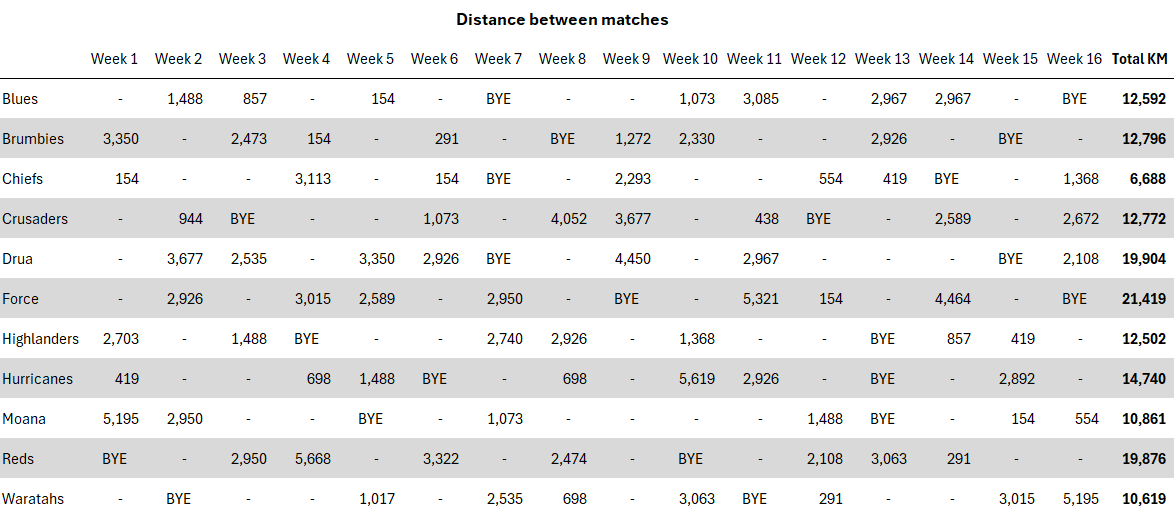

Let’s take a look at this year’s fixtures, with the following table showing the distances each team travels per week (in km) in 2025, with ‘BYE’ indicating a week off and ‘—’ marking home games:

There are some obvious equity issues there, with three teams—the Drua, Force, and Reds—travelling considerably more than any other team (far right column). The Chiefs, based in Hamilton New Zealand, travel just 30% as many kilometres as the Western Force.

A fairer target per team should be ~14–15,000km, which could be achieved by simply changing the order of the match-ups.

For example, the league’s organisers could give teams like the Fijian Drua and Western Force longer road trips, such as three away games back-to-back, reducing the number of lengthy return flights. While this may mean spending more time away from home, it minimises the frequency of long-haul travel, which can contribute to fatigue—especially when compounded over an entire rugby season. It wouldn’t be unfamiliar to players, organisers, and fans, either: when South Africa was part of the tournament they would regularly travel abroad for a few weeks at a time, as would Australian and New Zealand teams travelling westward.

To ease the travel burden further byes could be awarded after such road trips, which would be an improvement on the seemingly random allocation this year—the Force’s first bye was sandwiched between consecutive home games in week 9, and again in the final week of the season… after yet another home game.

Make it make sense!

But perhaps I’m mistaken—I am but a simple economist, not a sporting league manager—so I thought I’d give Grok the data and ask it to take a look. Here are its (lightly edited) ideas for how to improve the scheduling:

- Cluster Trans-Tasman Trips: Schedule consecutive away games for Australian teams in New Zealand (and vice versa) to reduce the number of long trips. For example, if the Force has games against the Blues and Hurricanes, schedule them in back-to-back weeks to avoid multiple trans-Tasman flights.

- Redistribute Byes: Use byes strategically to give teams a break after long travel stretches, especially for Australian teams and the Drua.

- Balance NZ-NZ and AU-AU Games: Increase the number of consecutive NZ-NZ games for New Zealand teams to slightly increase their travel, and schedule more AU-AU games consecutively for Australian teams to reduce their trans-Tasman trips.

- Minimise Long Trips: The Force and Drua’s travel is high due to their isolation. Cluster their trips together to minimise repeated long flights.

Claude came up with similar solutions—its full response, including my initial prompt for those interested in these sort of things, is available here.

Anyway, at the end of the day if your goal is to have a truly national game with a competitive top-tier league where every team has a realistic shot at winning, then you need to pro-actively deal with the structural disadvantages that teams based in places like Perth and Fiji face.

If the issues I’ve detailed above remain unaddressed, then clubs like the Force will continue to struggle on and off the field, making it harder to retain talent and grow their fanbase, putting rugby at risk of losing more ground to other sporting codes—a fate made all the more likely with the recent announcement that the Perth Bears rugby league team will be entering the market in 2027.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!