The budget update, workers not jobs, the costs of industrial policy, one year of Milei, and the bullish case for hydrogen

It’s now just six days until Christmas and with most offices about to shut down, so too will Aussienomics. But I’ll be back before the end of the year; there’s just too much going on in Australia and the world right now for me to stay quiet for long!

To get you through until then, here’s my longest post of the year on some of the things I found interesting this week.

Deficits forever

The federal government’s mid-year economic and fiscal outlook ( MYEFO), which basically gives us an update about what has happened since the 25 March 2025 budget, was depressingly bad. Here’s the Guardian’s summary:

“Cumulatively, deficits are $22bn worse over four years, with the deficit projected to increase to $46.9bn in 2025-26, or 1.6% of gross domestic product (GDP), before falling to $38.4bn in 2026-27 and $31.7bn in 2027-28, back down to a deficit of 1% of GDP.”

That’s despite revenue being revise up by $18.8 billion. The problem? Real spending is growing at 5.7% this year, well above what Treasurer Chalmers promised. Here’s the AFR:

“Real government spending was originally budgeted in October 2022 to be a relatively low 1.8 per cent in 2024-25. The almost 4 percentage point blowout shows why Chalmers’ claim that average real spending growth will be 1.5 per cent over the six years to 2027‑28 is a charade because it fails to factor in inevitable new future spending.”

As as result, the federal government’s share of GDP will increase to 27.2% in 2025-26, “the highest since 1986 – excluding the pandemic – just before the Hawke-Keating Labor government began a fair dinkum fiscal repair mission”.

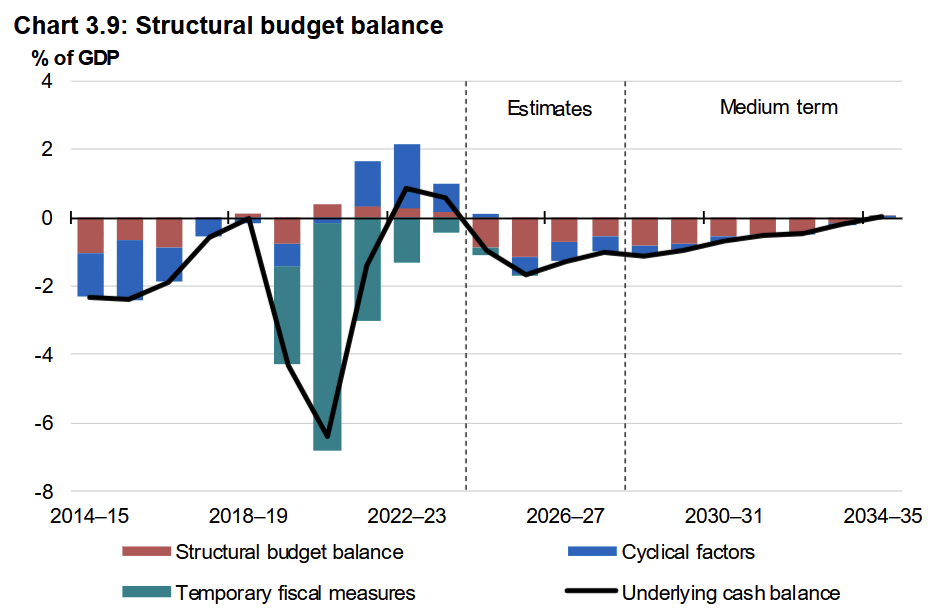

For me, the most shocking chart was the one that showed that the budget remains deeply mired in structural deficit:

Structural fiscal deficits, by definition, require economic and tax reform to resolve; they don’t just go away when China unleashes another big stimulus, or the RBA over-juices the economy with easy monetary policy. To get rid of them requires a government to make conscious and deliberate choices to reform, as Hawke and Keating did.

So, what are Treasurer Chalmers and Finance minister Gallagher doing about it? Nothing; they simply deflected any and all responsibility by saying that the result is “almost half the $47.1bn deficit we inherited for this year from our predecessors”, and that the deficit widened because of “urgent, unavoidable or automatic spending”, all while completely ignoring the fact that their own policy decisions made the outcome many billions worse than it would have been if no decisions were taken at all.

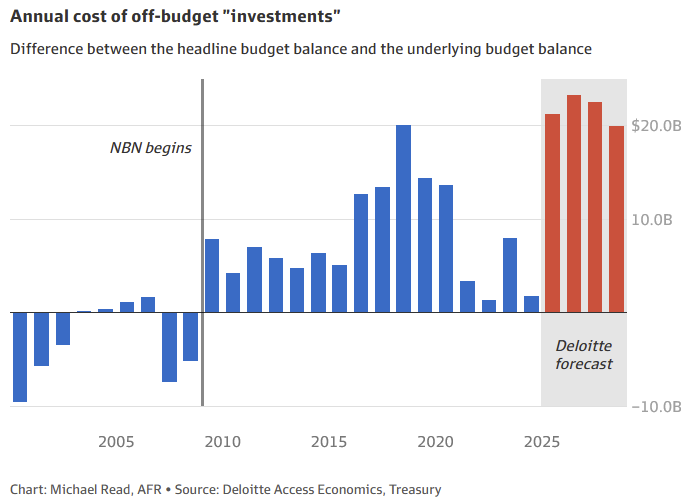

Yes, the Scott Morrison government’s spending was irresponsible. That government continued many COVID programs for far too long, and are the ones who kicked off the pattern of “hidden” spending on industrial policy, which is now up to $90 billion.

But today’s structural deficits are a policy decision of the current government. They could fix it, but they’re making the choice not to, for which they need to take full responsibility.

Look after workers, not jobs

Technological disruption – Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” – is a feature of market-based economies. People innovate, new patterns of specialisation and trade are discovered, and the old ways of doing things are gradually relegated to the scrapheap of history.

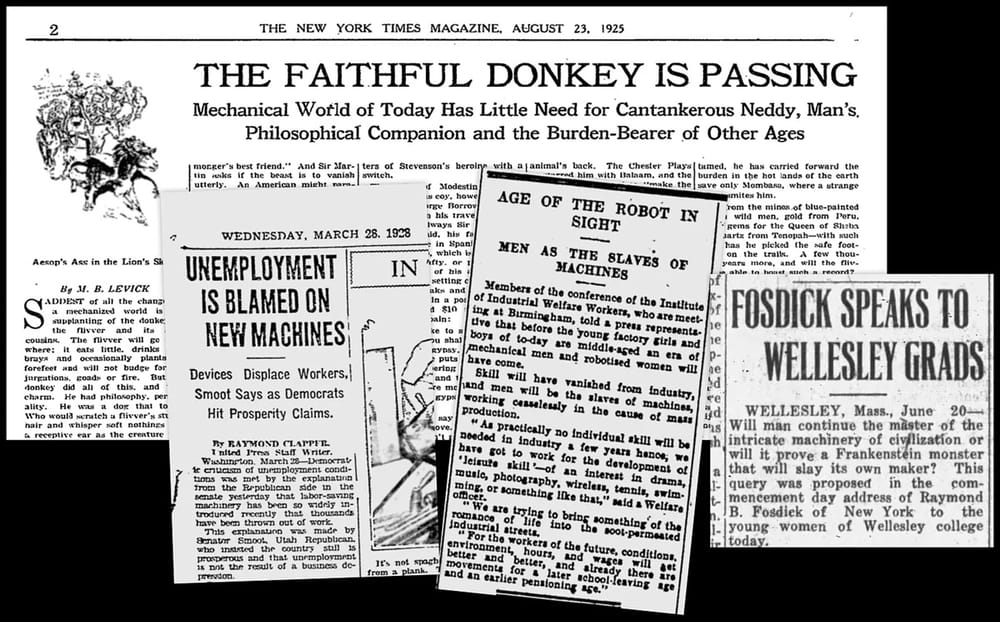

Jobs related to those tasks become obsolete, as the firms employing workers in those roles either adapt or fail. Lamplighter, Ice cutter, Elevator operator, Switchboard operator, Milkman – these are all once-popular jobs that have gone extinct. Each and every time, the future of work and employment is brought in to question:

Artificial intelligence (AI) is just the latest in the long line of disruptive technologies. And as with just about every time before, the cries for the government to “do something” are growing louder.

Most recently, the ACTU recently commented on some recent work done by the Social Policy Group (commissioned by the Australian Industry Group), which found that “one in three Australian workers are at risk of job loss by 2030 from the introduction of AI”:

“We need a fair go in the digital age. Today’s research underlines what unions have been saying for a long time: workers have a right to a strong say in the future of work. We can’t let multinationals and the biggest businesses make all the decisions on AI.

Every Australian worker and small business will be alarmed by this research that shows one in three workers at risk of job loss from AI. Unions will never accept workers being left behind.

This research underscores the importance of union campaigns for a Future Made in Australia to create the jobs of the future, reinvigorating our TAFE and vocational training system, and investing in new jobs for a clean energy future. These policies by the Albanese Labor Government must be built upon to deepen and diversify Australia’s economy – so we are building a better future for all workers.”

Almost all of those recommendations would invite stagnation, reducing the living standards of all Australians, including the ACTU’s members.

For example, when the ACTU says “we” without specifying who, it can only mean it wants politicians and bureaucrats to “make all the decisions on AI”. That would be extremely bad for Australian productivity, wages, and workers in the long-run, as our companies would fall behind those in other countries that have the freedom to make their own decisions.

Jobs would be “saved”, to be sure, but at the cost of future income growth.

As for the idea of creating “new jobs for a clean energy future”, that shouldn’t be a goal at all. In fact, we should want as few jobs as possible in the clean energy sector. If all the “jobs of the future” are in clean energy and manufacturing, then you can almost guarantee that those sectors will have high labour costs, reducing their competitiveness, raising the price of electricity and the products Made in Australia relative to imports and fossil fuel alternatives.

If anything, we should want the “clean energy future” to produce as few jobs as possible, so that it can truly compete with fossil fuels without wasteful subsidies, and labour can be freed up to work on other important, more productive tasks, whether it’s building houses or maintaining the robots themselves.

The only good idea the ACTU had was to “reinvigorating our TAFE and vocational training system”, as retraining can be critically important for workers during periods of disruption, although on that I’ll reserve judgement until the ACTU defines what it means by “reinvigorating”.

A very sad trend

Speaking of a Future Made in Australia, economist Alex Tabarrok recently linked to a Freakonomics podcast with Fareed Zakaria, who lamented the consequences of America’s descent into industrial policy:

“ZAKARIA: You can see it in what happened a day after the election results became clear. You got a flurry of tweets from every major C.E.O. in America — every major tech C.E.O., every bank C.E.O. — fawning over Trump, congratulating him and telling him how much they wanted to work well with him. I think that this is a very sad development that’s happened. It’s not entirely because of Trump. But we have politicised the economy in America. All this industrial policy, these tariffs, these bans. What that does is it suddenly makes Washington a very crucial arbiter to the success of business. You add to it Trump, who personally loves the idea of fining Caterpillar for doing this and Harley Davidson for doing that and Chase for doing — he views it as his job as president to literally dole out rewards and punishments to companies, depending on whether they do what he regards as the right thing or the wrong thing. It’s deeply saddening to me as somebody who grew up in India, where this is business as usual. Every business had to slavishly pander to whoever the prime minister at the time was. And you see it in Musk. Tesla stock, in the two days after Trump won, was up 20 percent or something like that, adding tens of billions of dollars to Elon Musk’s net worth. Nothing fundamental in the economics had changed for Tesla. There was just an expectation, now that he was a friend of Trump’s, that he was going to somehow be showered with federal largesse. You know, there’s a guy in India called Adani who’s Modi’s best friend, and his stocks trade at multiples 10 times that of every other Indian company. Because everyone assumes that at the end of the day, being Modi’s best friend is worth $100 billion or something like that.

DUBNER: That’s probably a pretty safe assumption.

ZAKARIA: It’s a safe assumption in India. What’s tragic is it might even be a safe assumption in America. But it’s not what the American economy was supposed to be about. And I think it’s a very sad trend.”

Modern industrial policy, on which a Future Made in Australia is modelled, is nothing but a rehash of the failed policies of the 60s, 70s and 80s. Politicians have always loved it because it appeals to their innate need for a legacy; for grandeur on which they can look back and say “I did that”. They can don their hard-hats, cut a few ribbons, and easily point to the number of “good jobs” created, or the billions invested due to their subsidies.

But what they never mention are the opportunity costs – the industries never started and jobs never created because of the resources diverted to their pet projects. Nor do they mention that the “new generation of manufacturing jobs”, as Albanese calls them, will not increase living standards in Australia:

“We find the manufacturing share is not significantly correlated with a higher standard of living. Nor is it related significantly and consistently to economic growth. We also find that trade restrictions both at home and abroad shrink the manufacturing base and smother economic growth. A better way than protectionism and subsidies specific to industry to enhance economic growth is to improve governance effectiveness and the quality of regulation.”

The larger the government and the more industries in which it directly meddles increases the opportunities for politicians to hand out favours, and for businesses to feel forced to bend the knee if they wish to prosper. This chart should be especially frightening, as it demonstrates how the federal government is increasingly politicising the business landscape with its various “investments”:

As Productivity Commission chair Danielle Wood recently warned, such industrial policy-related spending “risk[s] creating a class of businesses that is reliant on government subsidies, and that can be very effective in coming back for more”.

Fun fact

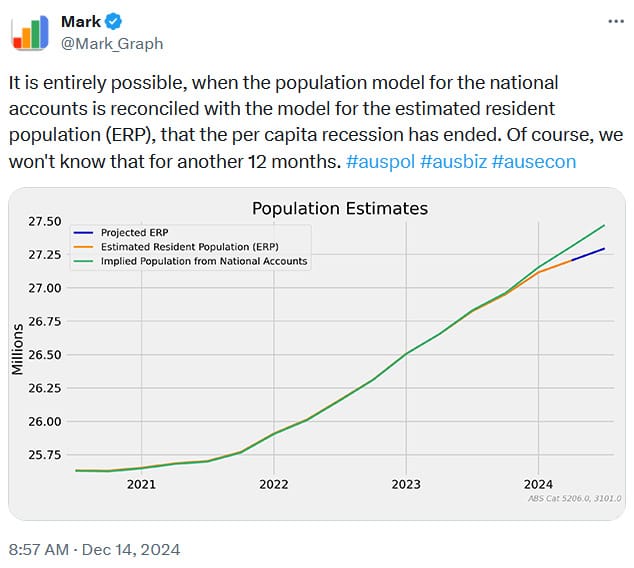

Australia’s per capita recession has been overblown for various compositional issues. The latest population data suggest that the national accounts data – from where the per capita recessions calculations are drawn – might have overestimated the post-pandemic rebound in population.

As always, beware knee-jerk policy responses to problems that might not even exist.

One year of Milei

Argentina’s recent budget under new President Javier Milei recorded a surplus – the first for 123 years. Structural fiscal deficits are a policy choice!

The economy is out of recession and reforms are continuing apace. That’s because Argentina’s deregulation czar Federico Sturzenegger, an MIT-trained economist, " spent a year and a half mapping the country’s regulatory landscape… [identifying] more than 4,000 laws, 70,000 decrees and countless resolutions that discourage investment and entrepreneurship, bar competition and damage productivity":

“He’s [also] discovered a rough rule of thumb: Where deregulation happens, prices decline in the range of 30%. He has seen it in textiles, logistics and some agricultural products—and the deregulation job is only 20% along.”

Australia is now bogged down with many of the same problems that have plagued Argentina for decades, and is in desperate need of reform.

So the question is: how long until Australia gets its own Milei? American economist Timothy Taylor recently pondered that very idea, drawing on new work from Tobias Martinez Gonzalez and Juan Pablo Nicolini:

“To understand why Argentinians would turn to Milei, it’s useful to ask the question: What if growth in your country’s standard of living had been lagging for decades. Moreover, what if you had had some experience with reforms that seemed to work in the 1990s and early 2000s, but now it felt as if the country was back on the same old treadmill of very sluggish growth and high inflation?

…

Argentina’s economic issues are recent a particular recent episode and not small. Gonzalez and Nicolini argue that, in the big picture, Argentina’s problems is overly large budget deficits. They write: ‘In this paper, we proposed a script of the economic tragedy of Argentina since the mid-1970s that contains a single villain: chronic fiscal deficits. The villain has the ability to manifest himself in seemingly different identities: sometimes a hyperinflation, sometimes a default, in other occasions a balance of payments crises’.”

When Argentina brought its deficits under control, it grew, only for the next government to come along and blow the budget again and eventually trigger another crisis. Rinse, repeat.

Unfortunately, history suggests that significant, Milei-level changes only happen when the situation gets intolerably bad. While the atmosphere prior to the Hawke-Keating reforms in Australia was one of “a fairly pervasive sense of national stagnation and decline symbolised by the early 1980s recession”, the motivation didn’t come from people “protesting in the streets for a floating dollar, free trade and low inflation”.

No, it came from a new government that “were not just interested in finding a new approach; they believed that a new approach was essential”, and they had the backing of the opposition. In other words, there was a broad consensus that something had to give – “that Australia had to engage in a global catch-up”.

As the next election approaches, I just don’t see that urgency from either side of politics. So to answer my question at the start: Australia’s not going to get its own Milei until we’re all a helluvalot poorer.

The bullish case for hydrogen

Long time readers know that I’m no fan of the big subsidies being rolled out to wannabe hydrogen producers. I believe that most of it will be wasted, and there’s just no good reason for our relatively small governments to be trying to manufacture a “winner” here when the technology itself has so many flaws.

But because of another government policy – Labor’s 2030 and 2050 carbon and renewable energy targets – they must persist, because finding a commercial use for hydrogen to soak up all of the excess day-time production is the only way they can plausibly meet those targets.

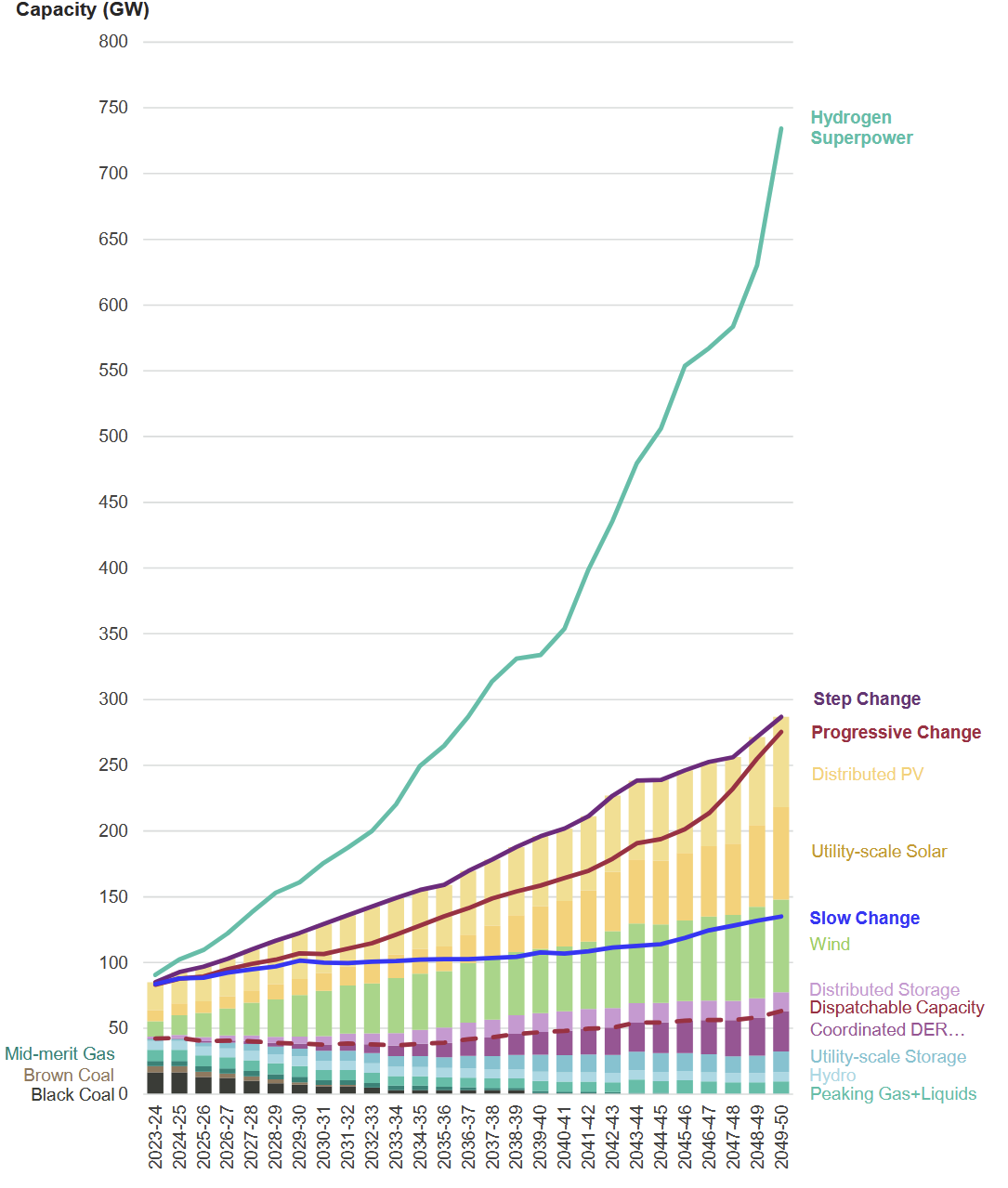

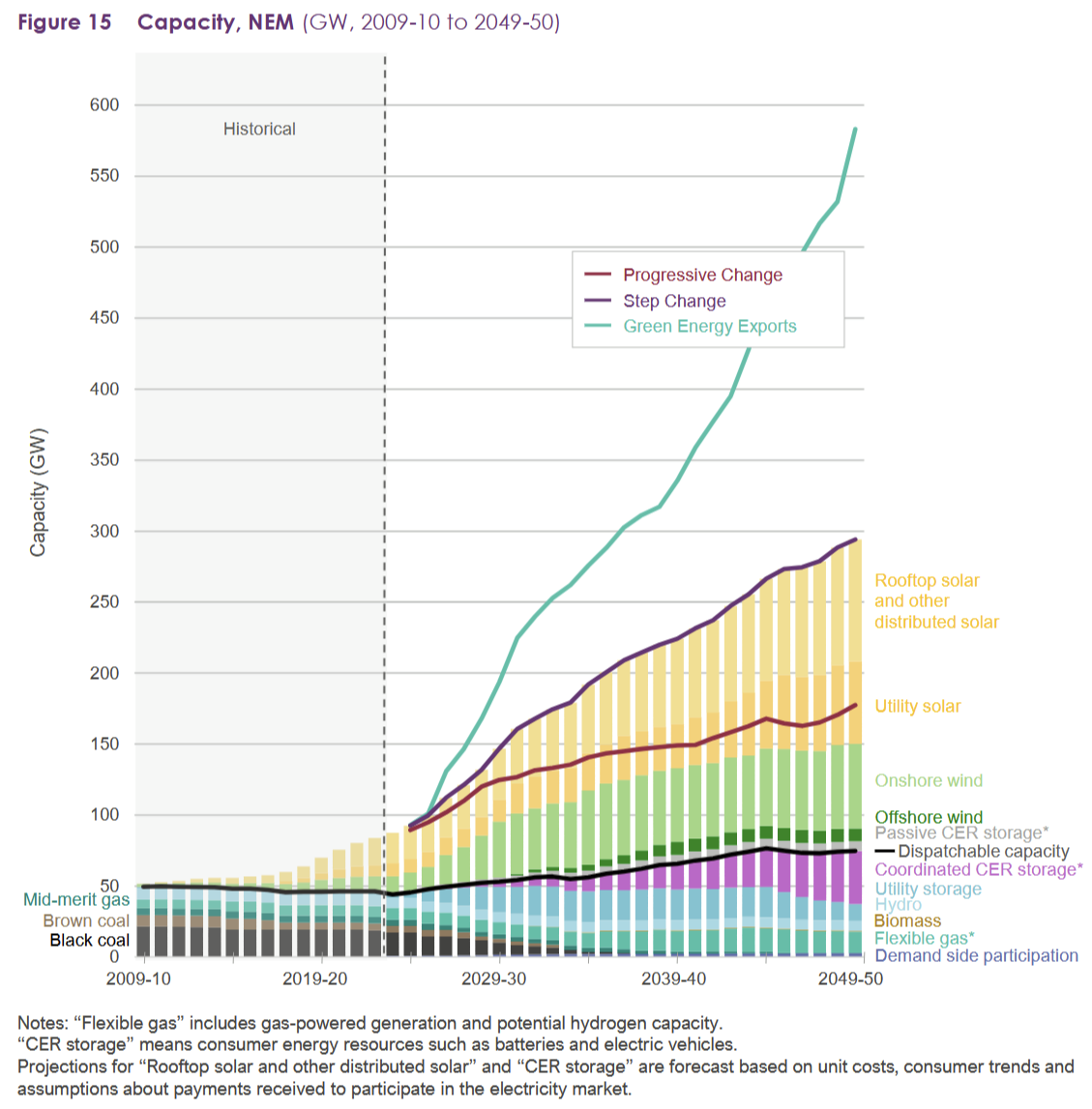

To visualise just how important hydrogen is, Australia’s 2022 Integrated System Plan (ISP) included a “Hydrogen Superpower” scenario, which was quietly dropped from the 2024 edition, replaced with a more vague but also unrealistic “Green Energy Exports” scenario:

Both are unrealistic because even if the technical problems with exporting hydrogen were resolved, the scenario would still require hydrogen electrolysers to be constructed at existing ports (presumably displacing existing export facilities), along with “10,000 km of [transmission] network in the next decade, and a total of 26,000 km through to 2050”.

But ignoring those constraints for a moment, what would it take for hydrogen the technology to work? According to Michael Puttré, quite a bit:

“While clean-burning, it [hydrogen] contains only about 30% of the energy per volume as methane, the main component of natural gas.

Also, hydrogen is only about 12.5% as dense as natural gas, so moving it through pipelines efficiently requires higher pressures. In fact, one method of moving hydrogen without compressing it is to mix it with natural gas to move through pipelines. This, however, requires blending in at one end and filtering out at the other—both of which add costs. Likewise, compressing hydrogen into liquid form for transport hikes the cost, particularly at the scale needed for use in energy production.

In addition to being difficult to store, the great challenge of hydrogen as a fuel is that it is also very difficult to transport at ambient temperatures. It is the smallest molecule and therefore has a tendency to permeate metals and polymers, increasing brittleness and possibly exacerbating fatigue and cracking. The fact is, the effects of hydrogen on piping, containers, valves and fittings are not completely understood.”

I get the attraction of hydrogen. It’s clean, it can be green, and it’s available everywhere that water is. But green hydrogen generated through electrolysis, i.e. using solar or wind power to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, is not very efficient and does not scale well. The most promising advances, as Puttré notes, are through methods like extracting it “from natural gas without emissions and without the need for carbon capture”, producing “turquoise” hydrogen.

As for uses, most are in niche industrial activities where natural gas is already used to make hydrogen, for example in fertilisers or nickel processing. Long distance freight is also a possibility, with diesel refuelling stations replaced with hydrogen facilities, which would be faster than charging a battery. Although even that might not be a fair comparison: battery swapping stations are already in use, and can " replace depleted battery packs with fully charged ones in mere minutes".

Puttré concludes that “Ultimately, industries will embrace hydrogen if it is more attractive than the alternative.” I agree. But while green hydrogen could theoretically be used for every activity, its limitations mean alternative technologies are probably going to be more attractive for most activities.

Hydrogen is akin to the jack of all trades, master of none, which is how it can end up included in completely unrealistic scenarios like those in the ISP, or have billions of dollars thrown at it in budget after budget.

Further reading

- Albo’s HECS debt forgiveness is just more demand stimulus: student loan forgiveness in the US " led to increases in mortgage, auto, and credit card debt".

- How not to do rail. “The [Queensland] government has revealed Cross River Rail’s budget has been blown out by $11.6b to $17b and won’t be operational until 2029. It was originally priced at $5 billion and due to open in 2026.”

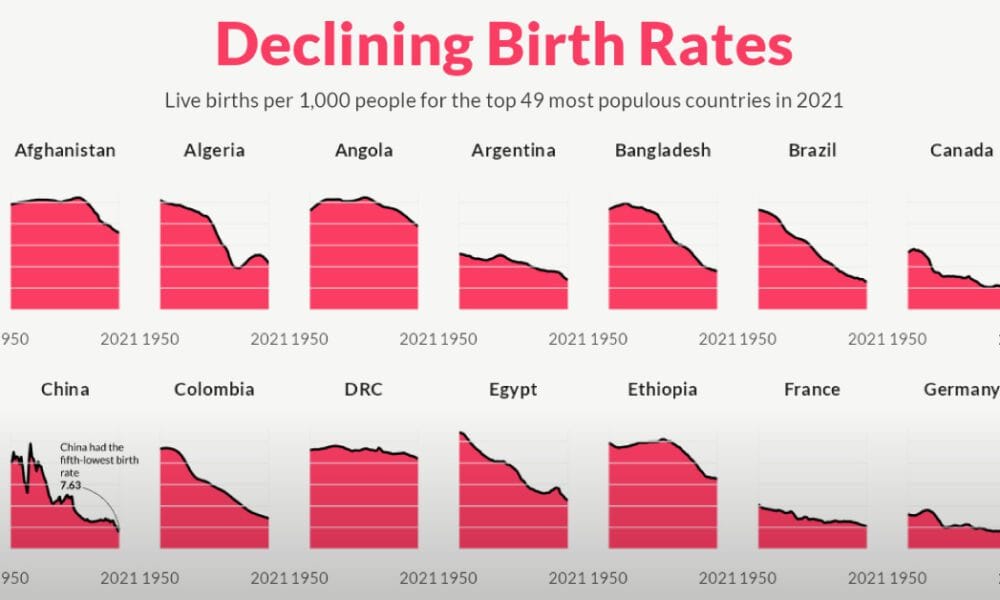

- Birth rates are falling in rich countries regardless of cultural differnces:

- The recent quantum breakthrough, while impressive, does not render existing encryption techniques obsolete. Your bitcoin are safe. “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics.”

- Nvidia is the the single-best performing stock in the S&P500 over the past decade. Its CEO, Jenson Huang, runs the company with a relatively flat hierarchy:

“He doesn’t want information that has already made its way through layers of management… The way he solved this problem was by asking roughly 30,000 employees at every level of the company to send regular emails to their teams and executives that even the CEO can access. Which he does—every single day. They’re usually brief and include a few bullet points, and glancing at them gives Huang a snapshot of what’s happening inside Nvidia.”

- New Zealand’s new conservative government is planning to run fiscal deficits of -3.1%, -4.1%, and -3.1% over the next three years:

“What’s the moral of the story? That National and Labour are essentially the same party, just run by different actors, sales folks and marketing directors who are pretending their two products are different, because they use different branding & colours. They’re like Coke and Pepsi Cola.”

- Subsidising supply, restricting demand – AKA China, where 30-year bond yields are now below Japan’s for the first time since 2006, suggesting a lack of investment opportunities in China’s economy:

“Prices for goods leaving Chinese factories have fallen year-over-year for 26 consecutive months, dropping 2.5% in November from a year earlier, and there is little sign of them turning up again soon. China’s gross domestic product deflator, a broader gauge of price levels across the economy, has been in negative territory for six consecutive quarters, the longest stretch since the late 1990s.”

- How today’s zoning laws would have killed Bob Dylan.

- There’s no such thing as a labour shortage. Politicians who listen to employers crying poor can lead “to multiple policy mistakes”.

Have a very Merry Christmas!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!