The dangers of neopopulism

David Leonhardt, a senior writer at the NYT, recently published a provocative column that spelled out the general consensus floating around elite circles these days. Namely, that industrial policy isn’t something that’s now simply accepted on both sides of of politics, but something that has been embraced. The change has been quite rapid, too; at a Berlin conference on the so-called “New Paradigm” last week, Harvard’s Dani Rodrik remarked that:

“Six years ago a conference like this would have been impossible. The agreement we now have on industrial policy, the lack of fundamental criticism… when I think about it, when I hear myself saying this out loud, I’m amazed.”

Why the rapid change? According to the conference Rodrik attended, it stems from “the inflation shock. And, decades of poorly managed globalisation, overconfidence in the self-regulation of markets and austerity have hollowed out the ability of governments to respond to such crises effectively”.

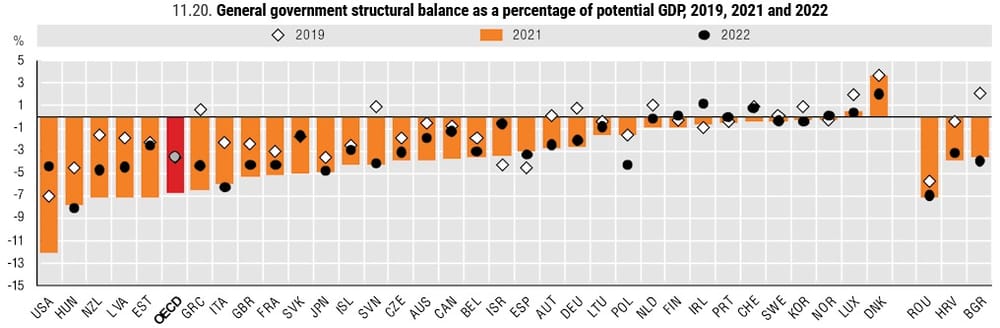

Notwithstanding the fact that, rather than austerity, the budgets of most global governments are in deep structural deficits, we seemingly have more regulation today than ever before, and that the recent inflation was caused by governments, basically what they’re taking aim at is what is commonly referred to as neoliberalism.

Has it really been that bad?

Before outlining his model, Leonhardt first defines neoliberalism as the late-1980’s agreements of “lowering trade barriers and ending the era of big government”, claiming that since then “incomes and wealth have grown slowly, except for the affluent, while life expectancy is lower today [in the US] than in any other high-income country”.

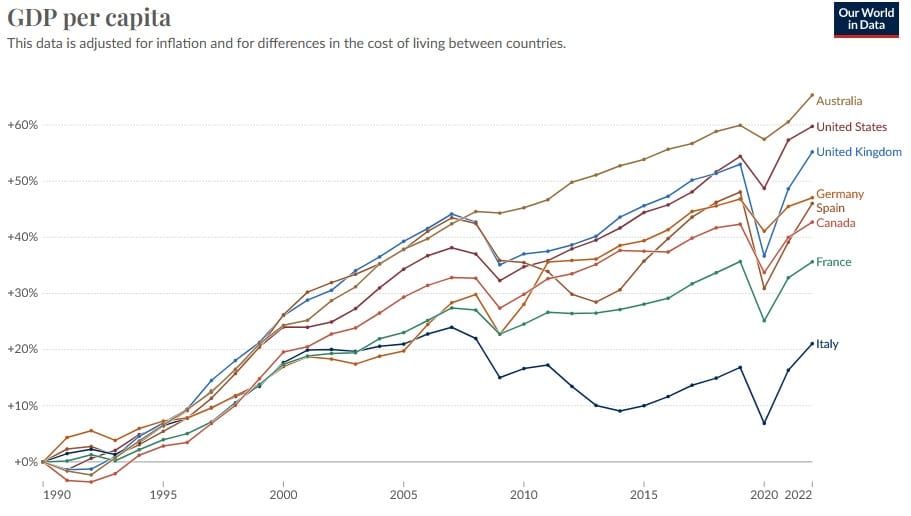

But a look at the data shows that the US economy been significantly stronger than the more heavily-regulated and bigger-government European economies. Our very own Australia, which undertook one of the developed world’s largest reductions in trade barriers since the Washington Consensus in 1989, tops the list of GDP per capita growth, with the US not far behind (Australia is only ahead because it was the beneficiary of a couple of mining booms):

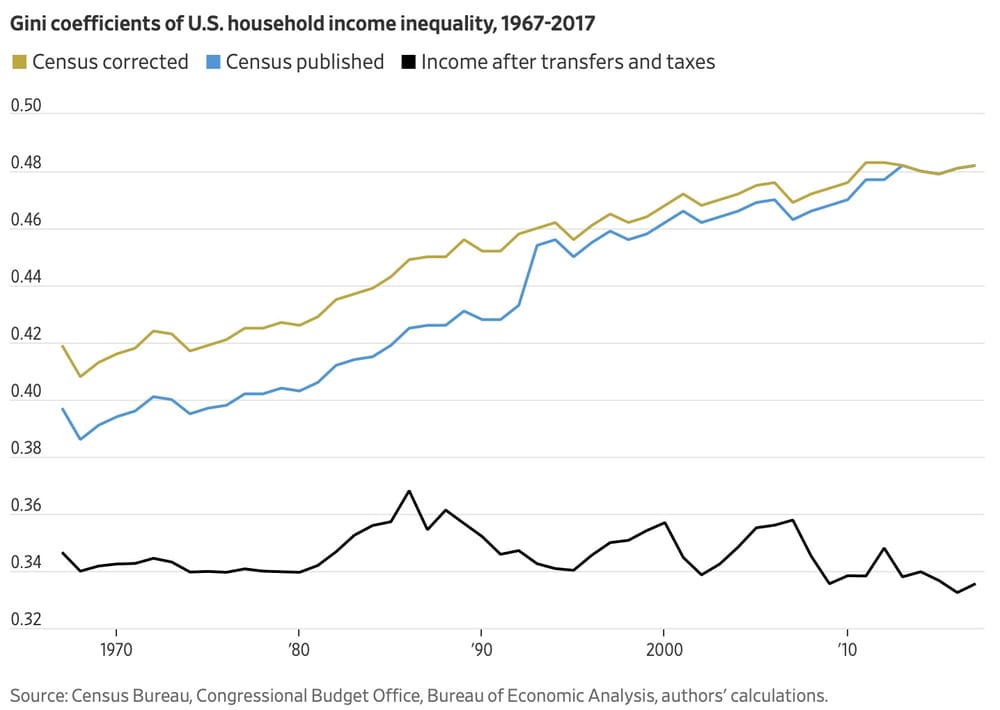

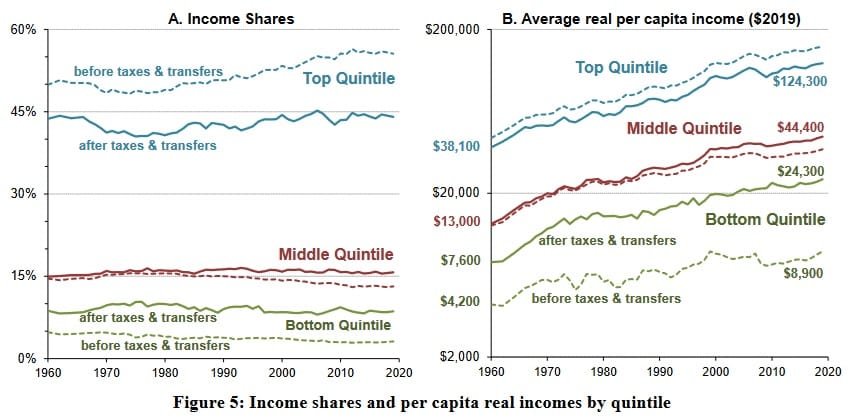

But you can’t eat GDP; was most of that growth concentrated on “the affluent”, as claimed by Leonhardt? That’s an important question, and is a very controversial topic in economics. It’s actually quite difficult to measure income inequality and the methodology selected has a large impact on what the results will show. For example, raw census data look pretty bad, but once you adjust for taxes and transfers, most of the change in measured inequality in the US disappears.

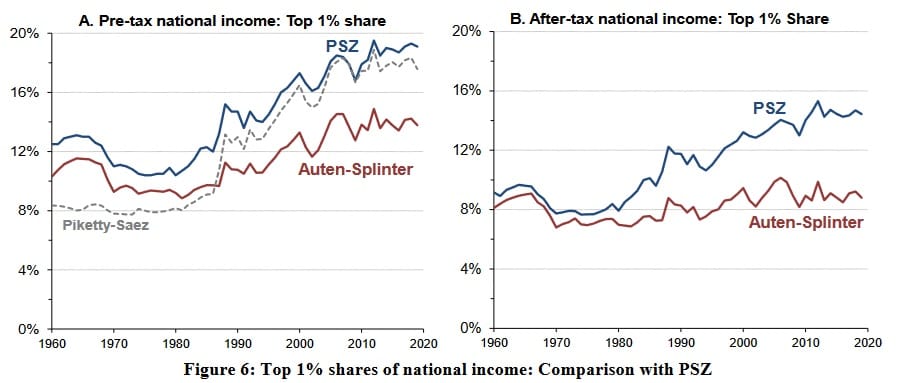

Similarly, while there is no denying that the share of income going to the top 1% has increased ( perhaps largely due to “the secular decline in interest rates”), there is significant debate about the degree of change.

Outside the top 1%, with a much larger economy, the poor in the US are still better off than those in many more-equal countries; after taxes and transfers, pro-growth and pro-trade policies have helped to raise incomes for all cohorts, regardless of their relative shares.

There are, of course, problems with a system where the top two income quintiles pay more than 80% of tax and those in the bottom quintile receive 90% of their income from the government. But that’s a topic for another day.

Culture matters

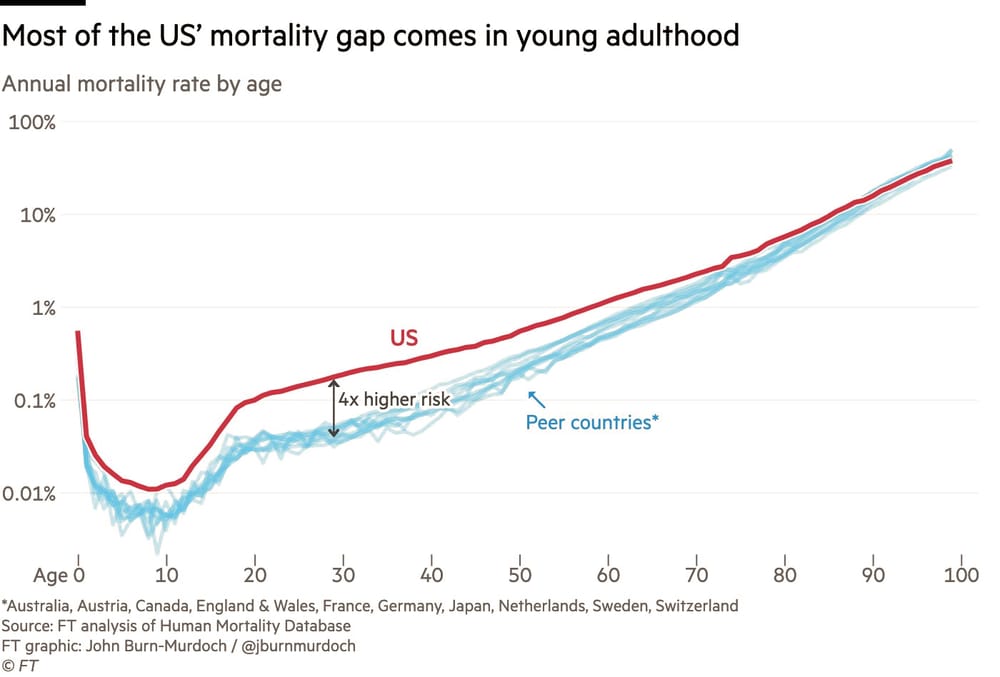

Leonhardt’s life expectancy claim is even more interesting. It’s certainly true that the average person in the US is expected to live a much shorter life than in most other high-income countries. But it’s hard to attribute causation to “lowering trade barriers and ending the era of big government”, especially when it’s not like the US went at it alone, and we don’t see these effects in other countries.

Fortunately, the FT’s John Burn-Murdoch covered the data in great detail last year, finding that drugs, guns, road deaths and obesity explain a lot of the difference. Those factors contribute to a lot of young deaths in the US; for example, a 5-year-old in the US has a 4% chance of dying before age 40, whereas a 5-year-old in Australia, Austria, Canada, England and Wales, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, or Switzerland has ~1% chance of dying before age 40.

If you live to 70 in the US, you can expect a similar life span as those in most other high-income countries.

Burn-Murdoch puts that difference down to the unique culture of the US, specifically the heavy focus on the freedom to be an idiot:

“[The] huge emphasis on personal freedoms means more guns, more dangerous/unsafe driving, more lethal vehicles than similarly developed countries. So a perfect storm of 1) more people pushed into bad situations, 2) easier for bad situations to become deadly.”

Those are social choices, not economic ones. Removing trade barriers and manufacturing subsidies was a constant for almost all high-income countries, including the US’s immediate neighbour to the north, Canada, which doesn’t have the same life expectancy problems as the US. In fact, highly restrictive countries such as Singapore, where even chewing gum was illegal for decades, have shown us that social freedom is not a necessary condition for economic freedom.

In other words, it’s the culture, not neoliberalism, that causes Americans to have a lower life expectancy than their peers in other high-income countries. And none of Leonhardt’s preferred economic policies, lumped together as “neopopulism”, would do anything to change the culture that is America:

“The new centrism is a response to these developments. It is a recognition that neoliberalism failed to deliver. The notion that the old approach would bring prosperity, as Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, has said, ‘was a promise made but not kept’. In its place has risen a new worldview. Call it neopopulism.

Both Democrats and Republicans have grown sceptical of free trade; on Tuesday, Biden announced increased tariffs on several Chinese-made goods, in response to Beijing’s subsidies. Democrats and a slice of Republicans have also come to support industrial policy, in which the government tries to address the market’s shortcomings. The infrastructure and semiconductor laws are examples. These policies feel more consistent with the presidencies of Dwight Eisenhower or Franklin Roosevelt than those of Ronald Reagan or Bill Clinton.”

Rodrik might call it a “New Paradigm”, and Leonhardt might call it “new centrism”, but there’s nothing new about what they’re proposing. It’s old school industrial policy, wrapped up in a new veneer of net zero and national security, and the outcome will be the same: directing resources away from the revealed preference of most consumers and workers into sectors favoured by government politicians and bureaucrats.

Good industrial policy is difficult

Now, to his credit, at least Rodrick’s plan acknowledges that it “is less about giving out subsidies and loans to sectors to stay in place and more about helping those invest and innovate towards achieving goals like net zero”.

And I’m all for that. For example, carbon taxes, or emissions trading schemes (ETS), can work well to achieve the government’s ends, and at least-cost:

“Using administrative data, we estimate that, on average, the EU ETS – the world’s first and largest market-based climate policy – induced regulated manufacturing firms to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 14-16% with no detectable contractions in economic activity. We find no evidence of outsourcing to unregulated firms or markets; instead… pricing the externality induces firms to make fixed-cost investments in energy-saving capital that reduce marginal variable costs.”

But we have no carbon tax or ETS in Australia, and the well of public opinion was poisoned by the Gillard government’s deception nearly 15 years ago, so we’re unlikely to ever get one. That means industrial policy in Australia will take the second-, third-, or fifteenth-best route, one that leaves it heavily exposed to political discretion. And when political discretion is involved, interest groups will spend up to their expected benefit on lobbying (known as rent seeking), even if the costs to society are considerably greater than those benefits; that time and money spent lobbying are resources that could have been spent creating value instead of destroying it.

A Future Made in Australia has only just started and that process has already resulted in billions of dollars for solar panels made in the Hunter Valley, and a quantum computer in Queensland that may well end up as the world’s most expensive paperweight. Society loses, but because the benefits are concentrated on a few and the costs dispersed across millions, considerable resources can be wasted on projects with low benefits and high costs.

Once again, there’s nothing new about this. We’ve been here before, and we know how it ends: with exploding budgets and lacklustre growth. But we’re not there yet, so there’s still time to reverse course. What we need is to put the emphasis back on weighing benefits and costs. As economist Steven Landsburg recently explained, that’s the most compassionate way to do policy, including industrial policy:

“[W]hen we teach cost-benefit analysis, what we’re really doing is teaching compassion—that is, we’re teaching our students to stop and consider all the people who are affected by a given action or policy before deciding whether to support it.”

Picking winners often makes you a loser

But not everyone in politics took Econ 101. For example, former Labor leader Kim Beazley last week claimed that critical minerals were “one place where unless you pick winners, you are simply losers”.

Right. Perhaps Kim is not aware, but for a long time our capacity to extract critical minerals was constrained and we were global “losers” precisely because successive governments spent many decades “picking winners”, such as BHP:

“The Broken Hill Proprietary’s monopoly position has inevitably influenced its decision making, not in the direction of unduly high prices or profits as the proponents of nationalisation feared, but rather in its failure to promote an adequate rate of growth, its failure to take risks and to show enterprise. Yet in this respect the company has been far from unique in the Australian setting; rather it has shown a reliance on government support and a reluctance to leave the safe havens of the domestic market which is a heritage of a hundred years of government assistance and tariff protection.”

When there are overarching political goals, such as achieving net zero or securing supply chains, we should be using the price system to achieve them, i.e. through tax reform. And if the government was seriously worried about national security, a more cost-effective alternative to direct subsidies might be to stockpile a quantity of certain goods, providing time for our supply chains to adapt during a true crisis.

I mean, let’s be realistic here. Securing downstream domestic production for “critical” goods is very expensive compared to the alternative of imports; how long would supply chains need to be disrupted to justify that investment? Unlike the US, we don’t have deep internal markets; bad trade policy will put us on the road to Peronist Argentina much more quickly than our American friends. We simply cannot afford to “secure” it all, ad infinitum.

Then there’s the question of how are we going to use our newly-secured domestic production? Remember, apart from WA and its reservation scheme, having plentiful natural gas and coal supplies certainly didn’t do all that much to insulate us from global energy supply disruptions when Russia invaded Ukraine. And if you’re talking about outright war with China, the best chance at avoiding annihilation would be a well-trained, well-equipped military to deter a much larger foe. To develop and sustain such a force requires income, and the best way to get that is by fully exploiting our comparative advantages while we still can.

Proponents of industrial policy, whether it’s being sold under the banner of a “New Paradigm”, “new centrism”, “neopopulism”, or a “Future Made in Australia”, all have one thing in common: they want to replace price signals and the sober calculation of benefits and costs with political discretion. But other than the catchy slogans, there’s nothing new about them, and they will inevitably end the same way as all prior attempts at import substitution industrialisation did: with less growth, insipid labour productivity, and a much poorer and more vulnerable Australia.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!