The end of climate decadence

The election of Donald Trump in the US didn’t just shake up global trade. It also saw a huge shift in how the world’s wealthiest nation was going to approach climate change. In the words of Trump’s energy secretary Chris Wright, the priority is now energy abundance:

“We are unabashedly pursuing a policy of more American energy production and infrastructure, not less. The Trump administration will end the Biden administration’s irrational, quasi-religious policies on climate change that imposed endless sacrifices on our citizens. The cure was far more destructive than the disease.”

If you ignore the vitriol, Wright isn’t denying climate change but is acknowledging there’s no free lunch and outcomes like net zero shouldn’t be pursued for their own sake, but with a cost benefit framework. Or, in his own words:

“The Trump administration will treat climate change for what it is, a global physical phenomenon that is a side-effect of building the modern world. Everything in life involves trade-off.”

Do I have confidence that the Trump administration will get the balance right? Almost certainly not. For example, when Trump declared a " national energy emergency" on his first day in office, it explicitly excluded renewables from the definition of “energy”:

“The term ’energy’ or ’energy resources’ means crude oil, natural gas, lease condensates, natural gas liquids, refined petroleum products, uranium, coal, biofuels, geothermal heat, the kinetic movement of flowing water, and critical minerals.”

But what there is no denying is that there appears to be a global shift away from climate decadence; an acknowledgement that trade-offs exist, and costly climate action isn’t the most socially beneficial policy to be pursuing in a world with elevated interest rates and soaring debt.

Politics trumps economics

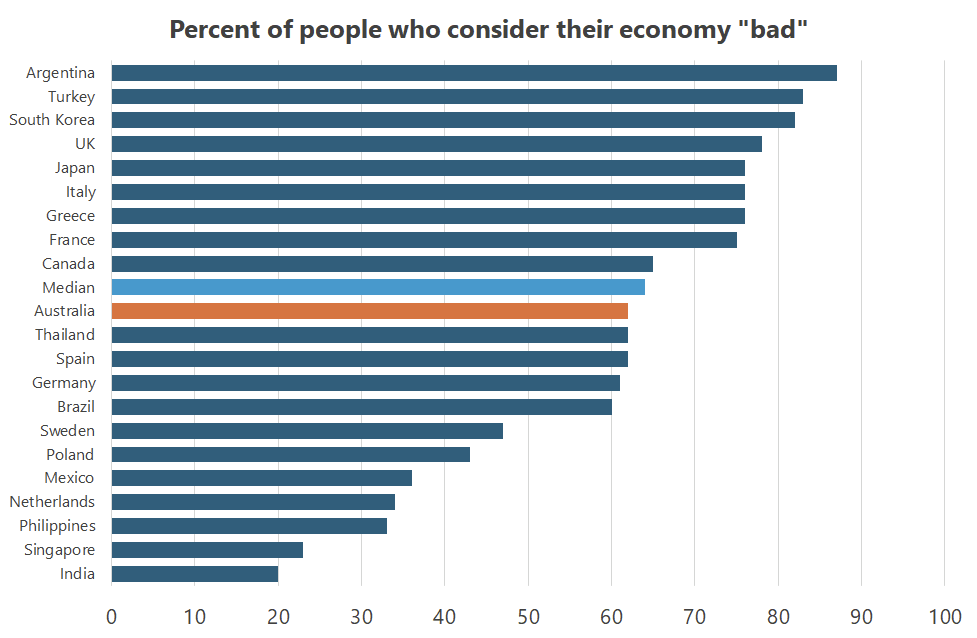

We saw it at elections around the world in 2024, where incumbents—often left of centre—lost almost every election they contested in 2024, with concerns about the state of their respective economies weighing heavily on voters:

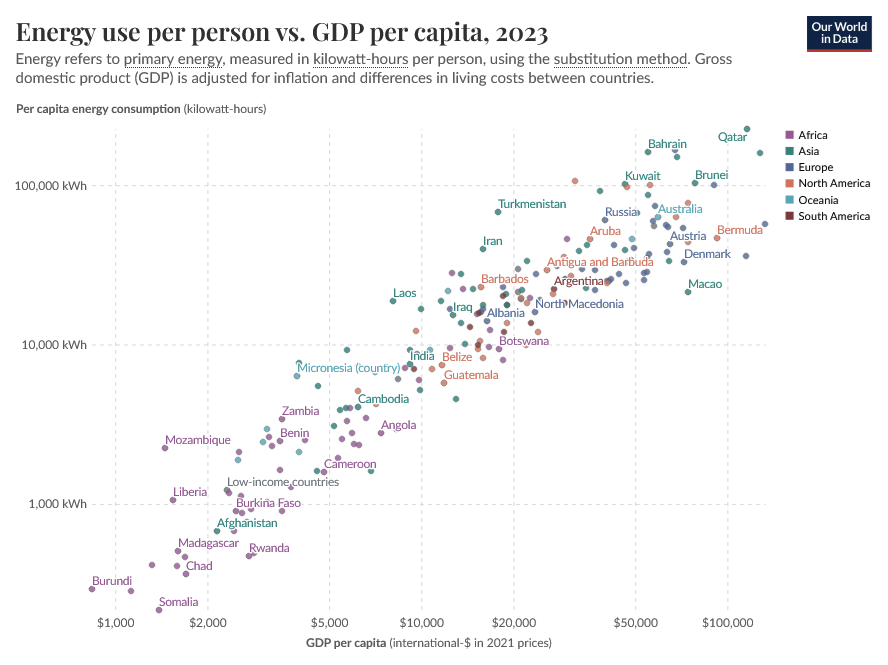

Energy use correlates exceptionally well with economic growth, enabling wealthier households to afford lighting, appliances, air conditioning, and even electric vehicles:

Just last week Canada’s new left-of-centre Prime Minister, Mark Carney—a man who had never run for, or held political office—officially handed in his economics union card by cancelling the country’s Pigovian carbon tax, calling it “too divisive — at a time when Canada needs to be united”.

Despite the fact that a carbon tax is very efficient and, provided it’s used to eliminate less efficient taxes elsewhere, socially beneficial, Mark Carney the politician knew better. He recognised that climate action—effectively a luxury good for people in advanced economies—is no longer close to being front and centre of Canadian (or global) discourse.

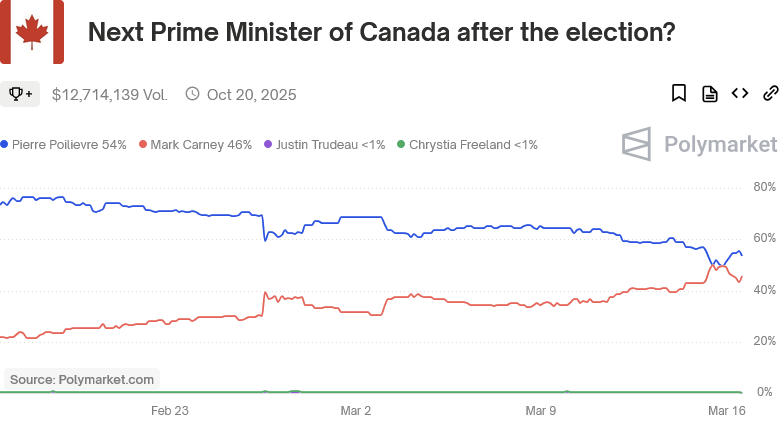

Carney also knew that repealing Canada’s carbon tax would boost his poll numbers, given that opposition leader Pierre Poilievre had been calling him “carbon tax Carney” for the past few months. Prediction markets now have the election as a virtual coin toss:

To quote Bob Dylan, the times, they are a-changin’. Even Australia’s hippie-in-chief, billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes, recently bought himself a private jet, for goodness sake!

People feel they’re paying too much for climate action

People care a lot about climate change, they just don’t want to pay for it themselves—especially when their sacrifice won’t even do anything to mitigate it. A report last year conducted by the OECD found that net-zero targets were likely to double the pace of annual job losses in high-emitting industries, putting around 7% of Australian jobs at risk. While those workers are likely to find new jobs, they still “face greater earnings losses after job displacement, averaging a 36% decrease over six years after job loss compared to 29% in other sectors”.

So, when the economy isn’t doing all that well and energy prices are rising, that’s when people really start to take notice. And given that Australians are only willing to pay somewhere in the region of $200 to take “action on climate change”, they might start to get frustrated when they realise they’re paying much more than that, either directly through greater taxes, or indirectly through higher energy prices and job displacement costs.

Resource constraints are real, and they’re coming back with a vengeance. As a recent Westpac analysis of the bond market concluded:

“The primary implication of these developments is that, for a given monetary policy stance, the yields at which governments borrow will be higher, placing upward pressure on borrowing costs and current and future deficits. Given the increase in interest costs a higher term structure brings, governments will need to become more considered about how they spend.”

For every dollar spent on climate action, that’s a dollar that’s not available to improve people’s life right now: whether it be on education, healthcare, or the cost of living.

The uncomfortable truth is that luxury goods such as climate action are no longer in vogue, with voters instead demanding more concrete policies like energy security and manufacturing resilience—in part because while climate action in advanced economies might make people feel good, it actually does very little for the environment.

A single country can’t solve climate change

William Nordhaus, a Nobel laureate in economics for his work on environmental issues, found that while climate change would be costly (the “Colossus that threatens our world”), the cost of mitigating it might be even more expensive—and so “the central questions about global-warming policy—how much, how fast, and how costly—remain open”.

That’s especially true if the world isn’t able to solve the free rider problem:

“No single country has an incentive to cut its emissions sharply. Suppose that when country A spends $100 on abatement, global damages decline by $200. However, country A might get only $20 of the benefits, so it would tend to decline the responsibility. Hence, if there is an agreement, nations have a strong incentive not to participate. If they do participate, there is a further incentive to miss ambitious objectives.”

Climate change is a global problem, and so unless the actions taken by a small country like Australia are able to credibly influence global policy, they may not be worthwhile—why should Australia impoverish itself when the rest of the world is free riding?

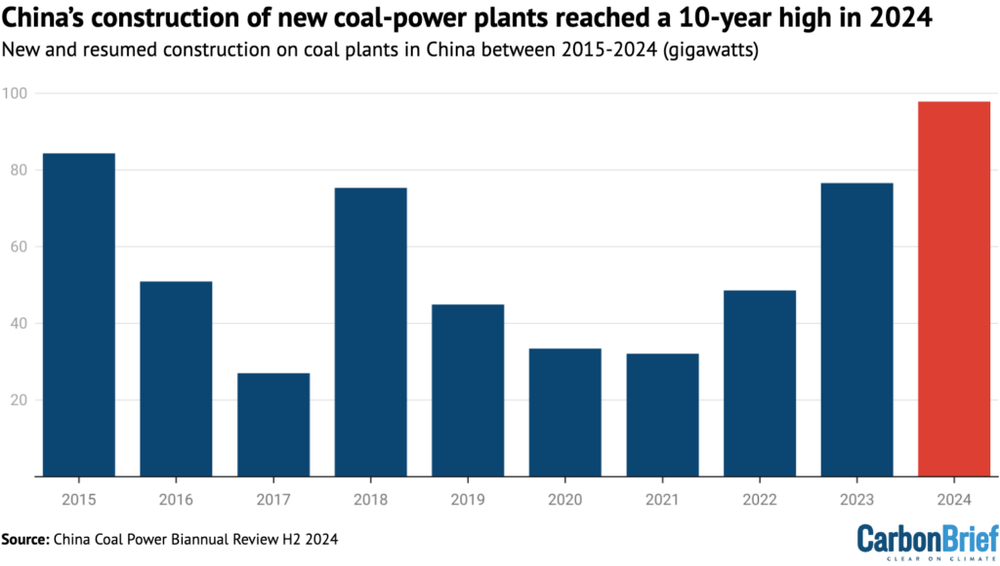

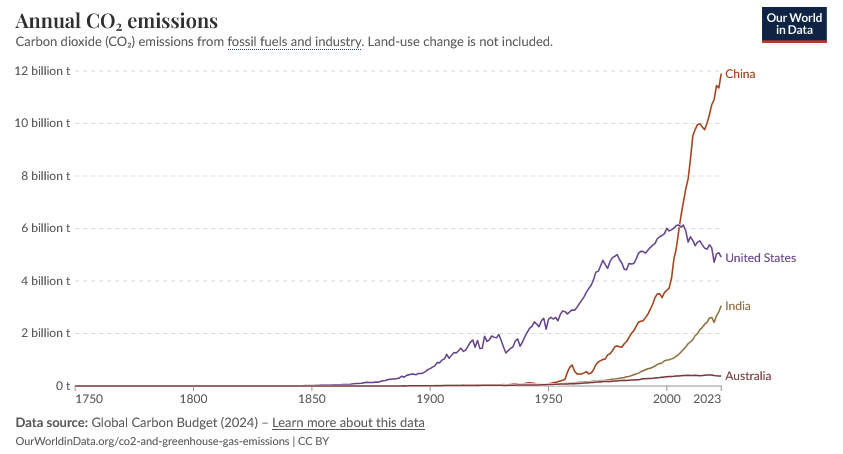

The election of Trump, the abandonment of the carbon tax in Canada, and China’s continued use of fossil fuels—it started building more coal plants in 2024 than at any point in the past decade—means that whatever Australia does is largely irrelevant for climate change.

The climate doesn’t care about per capita emissions, so when the world’s largest polluters are also the biggest free riders – and one of them is even a geopolitical rival – it doesn’t make much sense to sacrifice growth for little benefit. Basically, China and India’s emissions will completely swamp anything Australia does.

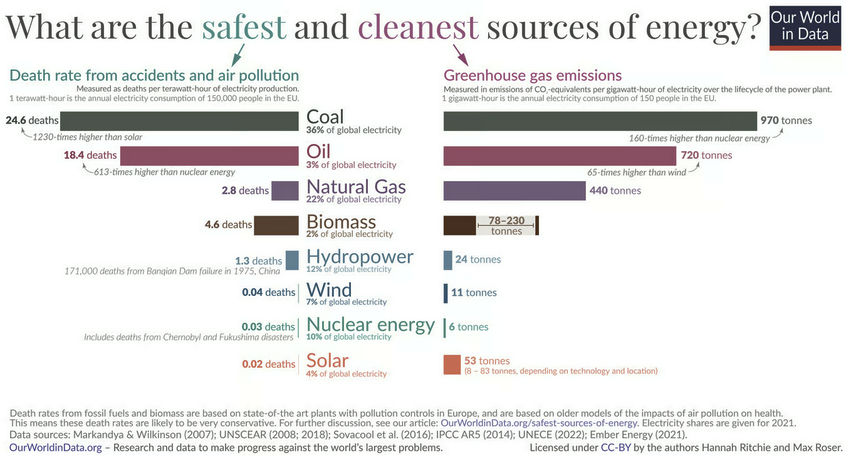

Now don’t get me wrong; I think the move to renewables is generally a good thing to do in its own right, as is the ultimate goal of net zero. Renewables offer local benefits like cleaner air, justifying their use even if global emissions continue to grow, unlike a carbon tax that’s reliant on global cooperation to produce benefits.

The fact is coal is incredibly dirty and unsafe, and while not using it in Australia will do nothing for climate change (it just lowers the global price of coal, freeing it up for someone else, e.g. China, to burn), I still think its phase-out in Australia is good policy (provided adequate gas and/or nuclear has been commissioned to replace it).

As an economist my preference would be for a Pigovian carbon tax that replaces more inefficient taxes, such as those on incomes, but that makes little sense in a world of free riders. And if you’re just after an efficient way to collect tax revenue, raise the GST instead (it’s regressive but you can fix that with transfers).

The right kind of industrial policy

The same logic also applies to the command and control approach of the Albanese government, and the Morrison government before it: if a revenue-neutral and highly efficient carbon tax doesn’t make political sense for Australia (or anywhere else), then neither does funnelling scarce resources into projects that are more likely to fill the trough of rent seekers than do anything meaningful for the environment or climate change.

For every dollar spent in the name of industrial policy like a Future Made in Australia, politicians and bureaucrats are effectively replacing market signals and incentives with their own preferences. The only certainty is that because such investments weren’t already occurring, the process involves a shift to producing lower-valued outputs. Productivity will fall and, in turn, so will real wages.

Now, that might still be desirable—say, from the vantage of national security. But the more we find out about a Future Made in Australia, the more it’s clear that the real goal is to create well-paid, low-productivity union jobs—" good jobs"—that produce outputs no one would want without hefty subsidies.

We’ve tried that kind of industrial policy at scale before, and it “was largely responsible for Australia’s secular decline in world economic rankings”.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no room for industrial policy at all. However, rather than picking winners and subsidising solar panels and batteries for wealthy households, the correct way to support Australian industry would be through removing the regulatory roadblocks to getting things done; abandoning arbitrary targets for renewables and emissions that make us poorer and less resilient; and acknowledge that while climate action is a worthy endeavour, that’s only if it’s done in tandem with improving the welfare of Australians.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!