The energy debate misses the bigger picture

It’s pretty clear by now that energy policy is going to receive a lot of attention in the lead-up to the next federal election, which must be held by May 2025. And the battle lines have been drawn: the Albanese government has committed to a renewables-dominant strategy, while opposition leader Peter Dutton will reallocate many of the subsidies flowing to renewables and the transmission needed to support them into extending coal’s role in the grid until – if – he can get some nuclear power going.

I think they’re both wrong because they’re not seeing the forest for the trees. Instead of focusing only on the means – i.e. nuclear or renewables – they should be focused on the objective, which is (or should be) energy abundance.

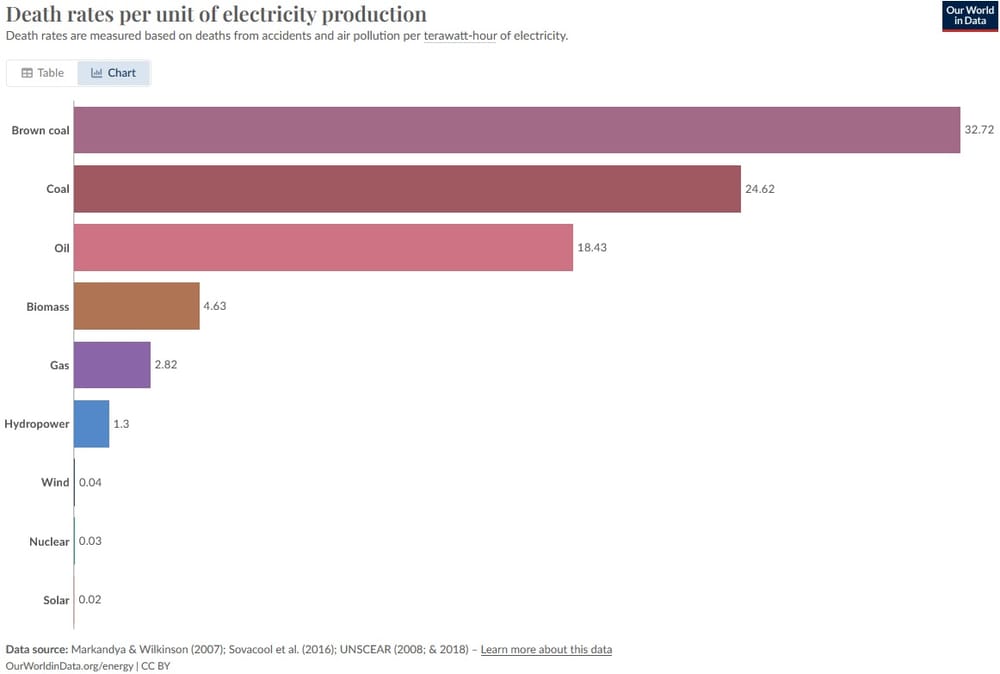

I know it’s a lot to ask for a politician, but that means they should quit it with the energy tribalism. For example, the current government shouldn’t be demonising what is a demonstrably clean, extremely safe source of energy with silly memes that would make even the Greens blush.

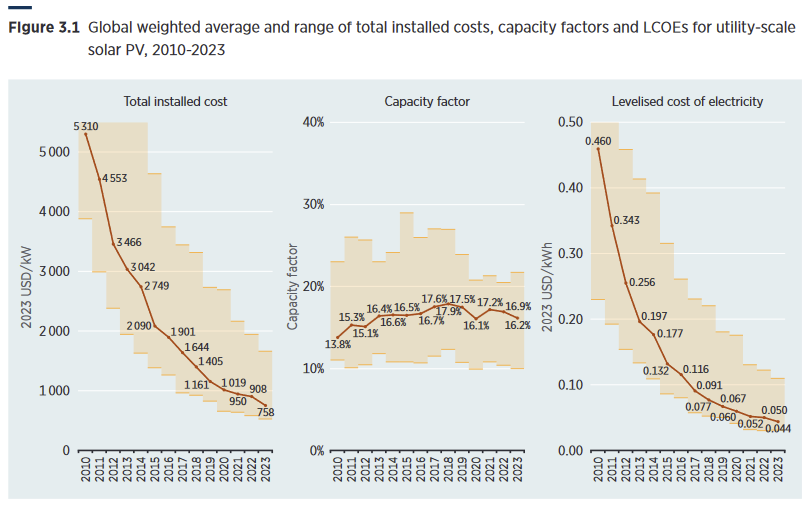

As for the opposition, Dutton should publicly embrace renewables so that investors have the confidence to build here, perhaps even reducing the amount of subsidies currently being handed out like candy on Halloween. After all, we live in a sunburnt country, in a world where solar prices continue to fall in a pattern resembling Moore’s Law. Of course renewables will make sense in Australia!

I would love nothing more than if both sides of the aisle would stop making energy a tribal “with me or against me” issue, and instead agreed on energy abundance.

All of the above energy policy

Physicist Casey Handmer recently wrote about water scarcity in the US and how it’s the binding constraint against development in the West. A lot of the US – like Australia! – is desert, making it less than ideal for humans to inhabit:

But that equation changes if you add affordable desalination into the mix. And how do you make desalination affordable? With abundant energy:

“I’m hardly the first to observe that cheap energy can radically transform Nevada, so here I’ll try to be more constructive. How do we do this?

We use cheap solar PV and, ideally, cheap desalination technology to generate millions of acre feet of water on the coast. We move the water inland. We release it onto the landscape to substitute for a lack of natural rainfall.

Not to disturb desert lovers (myself included) too much – more than 90% of the state, including all existing National Parks, State Parks, and military bases, would remain unaffected by this project. There is plenty of empty land to go around.

How much would it cost? Baselining on the CAP and the earlier analysis of low cost desalination, I project:

$4b for a 20 GW solar desal array

$4b for a matched low cost desal plant

$6b for canal construction, based on the CAP in Arizona and adjusting for scale.

$2b total for pumps and solar arrays to power them

In all, ~$16b to restore a huge swath of the Pleistocene ecosystem, with over $1t of realisable value generation, in addition to ongoing revenue from development.”

I’m not saying Australia needs to sprawl out and create new cities, at least not yet: Australia has some of the least dense cities in the world! But pie-in-the-sky projects like this are just the beginning of what’s possible with abundant energy. Solar might one day unlock entirely new cities, while nuclear looks to be perfect for growing industries such as the data centres that will power our future AI overlords.

What about a Future Made in Australia that actually revives Australian manufacturing? You’re going to need cheap energy to power the machines, not endless subsidies and negative-productivity jobs.

But such possibilities require an energy policy that leaves no stone unturned, with all options on the table. It means an energy policy that avoids costly path-dependent “lock-in”, where we can’t pivot to what works because it would be too politically costly to do so.

The good news is that such an approach is popular among voters, to the extent that the preferences of Americans are aligned with Australians:

“When presented with a choice among three options—a rapid green energy transition, an ‘all of the above’ energy policy, and emphasising fossil fuels—American voters across demographics and partisanship strongly prefer an ‘all of the above’ approach to energy policy including oil, gas, renewables, and nuclear. Less than a quarter support a rapid transition to renewables, which drops to under a fifth for working-class (noncollege) voters. Even among Democrats, support for a rapid transition is only a little over a third.”

But politicians don’t appear to have got the memo, or are too beholden to vested interests to care. A good example of the wrong thing to do would be the Albanese government’s vast renewable energy subsidies. The government hopes that by subsidising producers, they’ll generate a big increase in the output of renewable energy prior to 2030. But by definition, the developers most likely to lobby for those subsidies – for which there is apparently “overwhelming demand” – will be those that get the most producer surplus from the subsidy.

Those misaligned incentives mean that while the subsidies will increase renewable energy generation, they will also create large deadweight losses that could be much greater than the benefits – namely, pulling forward renewable energy generation by a few years.

An ‘all of the above’ energy policy also requires politicians to stop making claims about the means to energy abundance, as minister for the environment, Tanya Plibersek, recently did when she claimed that Australia will be “a renewable energy superpower”.

We should want Australia to be an affordable energy superpower, not necessarily a renewable energy superpower! It’s not much good being a renewable energy superpower if you can’t use much of it because it’s prohibitively expensive.

Similarly, when the minister for energy, Chris Bowen, boasted that “20% of all announced Hydrogen projects around the world are in Australia”, it’s not the flex he thinks it is. The fact that Australia – a country where 0.3% of the world’s population live, with just 1.6% of the world’s GDP – is sinking so much capital into a technology no one else seems to care for should be a warning sign, not something to be boasting about.

As the great Chinese reformer Deng Xiaoping once said, it doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice. We should adopt the same approach to energy policy: solar, wind, nuclear, batteries, hydro, gas, coal; it doesn’t matter, so long as energy is plentiful.

Reducing Australia’s pollution and carbon emissions are goals that will be much easier to achieve if energy is abundant!

Problems with the current approach

After initially embarking on a renewables-only plan, the Albanese government eventually admitted that such a model is simply too unreliable to power the nation’s grid by itself. But it’s also steadfastly sticking to its arbitrary targets, like ensuring renewable energy makes up 82% of the Eastern seaboard’s market by 2030.

But why? There’s no clear reason why eliminating most of the carbon in Australia’s energy grid, which accounts for less than 30% of the country’s total emissions, is the best place to do it – let alone by 2030!

Furthermore, attempting to ‘pull forward’ so much renewables investment, as the Albanese government is doing, risks destablising the entire industry. There’s already a long list of projects scheduled for 2030 – likely because of the government’s target – which will soon create bottlenecks, extending lead-times and raising costs for investors and project owners.

Green energy investments generally aren’t a good deal, so trying to cram so much into a short period of time, before affordable firming options like gas or batteries are ready for it, risks inflating costs and driving those already-low returns deep into the red. As Aswath Damodaran recently observed:

“There are some who will argue that the money spent on green investing has given rise to innovation and new technologies, but I wonder whether that innovation and those technologies are the ones that we would have invested and developed, without a firehose of capital raining down on green enterprises. There is research starting to percolate through the system that we could have made a much bigger impact on greenhouse emissions by spending our R&D on brown innovations, i.e., innovations that make fossil fuels cleaner-burning and less damaging, than on green innovations, i.e., innovations that explicitly focus on just green energy. More importantly, and as noted earlier, it can be argued that the impact investing definition of alternative energy excluded the one source of energy that has had a track record of making a significant impact on energy consumption, i.e., nuclear energy, and spending a fraction of what was spent on nature’s energy sources (solar, wind and hydro) on developing safer ways of delivering nuclear power would have moved the fossil fuel dependence needle by far more.

In short, green investing, in the aggregate, has failed in terms of delivering financially (both in terms of business building and delivering returns for investors) and socially (in terms of reducing dependence on fossil fuels). It is the point that I made in my post on impact investing, where I argued that the prime beneficiaries of the movement have been the consultants, green fund managers, advisors and academics who live in its backwaters.”

The Albanese government’s solution to the renewables-only problem is a “future gas strategy”, which also pledges “that no federal money will flow to gas companies”. That might sound like an acceptable trade-off to green energy advocates, but it’s not quite that simple.

For while Australia might have a lot of gas, most of it is not located where it’s needed. It’s also expensive to extract: the reason why most of our exploited gas is converted to LNG and shipped overseas isn’t because we’re giving “most of it for free” to foreigners, but because committing to long-term contracts ex-ante was the only way to make extracting a resource with extremely large fixed costs economically viable.

Fun fact: if the Australia Institute had its way, WA’s gas wouldn’t be exported or used domestically, because no one would invest in it!

Fun fact: if the Australia Institute had its way, WA’s gas wouldn’t be exported or used domestically, because no one would invest in it!

Such costs pose a significant hurdle to both the Albanese government’s plans – and those of Peter Dutton, who is relying on plentiful gas to keep the lights on until nuclear can get up and running

Earlier this year, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) “warned of immediate risks to gas supplies on the east coast”, and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has “predicted shortfalls from 2027 [that] highlight the need for additional gas supply”.

There’s also a huge amount of global LNG coming online in the next several years – a nearly 50% increase in the world’s export capacity – which the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects to depress prices for decades:

“If gas markets are to absorb all the prospective new LNG supply and to continue to grow past 2030, this would require some combination of even lower clearing prices, higher electricity demand and slower energy transitions – with less wind and solar, lower rates of building efficiency improvements, and fewer heat pumps – than projected.”

But cheap gas is good, right? Not exactly: such a glut makes it less like that investors will be willing to bankroll a further expansion of Australian gas, given the significant up-front capital investment needed to extract it. And importing gas can be costly, as the Grattan Institute pointed out:

“An increased role for gas means getting someone to pay for new infrastructure, such as pipelines or LNG terminals. That will make for expensive gas, and expensive gas means expensive electricity.”

Add to that the heightened political uncertainty surrounding large projects in Australia – there’s a strong negative connection between a government’s policy unpredictability and investment activity – and the task becomes even more difficult.

So, either our governments start subsidising fossil fuel extraction themselves (at huge cost), or we slow the renewables roll-out – i.e. ditch the 2030 target – until we can be sure that the grid can support them.

The eventual answer might even be a combination of the two, as is happening in Victoria where the state government recently wound back a ban on onshore gas exploration and development, and is reportedly “examining a floating liquefied natural gas terminal in the south-west of Port Phillip Bay, as it faces up to prospect of gas shortages across the state from as early as 2027”.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!