The federal election, Trumpian uncertainty, Europe goes to war, and Australia's political productivity problem

Barring major cyclonic damage from Alfred as it barrels into Brisbane tomorrow morning—for those of you in its path, stay safe!—Albo appears all but certain to call an election on either Sunday or Monday, after the week’s expenditure review committee (ERC) meetings were all reportedly cancelled.

Without those ERC meetings, you can’t finish the Budget that’s pencilled in for 25 March, which can only mean that Albo expects the government to be in caretaker mode on that date—implying an election on 12 April, which would be 33 days from Monday (the minimum permitted campaign duration).

While Albo won’t be able to dodge the next RBA meeting—rates will almost certainly be left on hold—skipping the Budget does allow him to try and shift the narrative away from his government’s economic credentials, which given the nation’s deteriorating finances, might be a wise move.

That’s because in place of a Budget might be an economic statement that allows the government to better control the narrative. Think glossy pages full of fluff about a Future Made in Australia and the recent Medicare expansion, but nothing about the record government tax and spending share of the economy, perpetual structural budget deficits, or the interest payments on the government’s growing debt.

I’ll probably have more on all that next week. For now, let’s talk about Trump (for a change!).

Chaos and uncertainty

I think, by now, it’s clear that tariffs—“the most beautiful word in the dictionary”—are not a bargaining tool for Trump. His address to Congress on Tuesday night (US time) made that very clear:

“Much has been said over the last three months about Mexico and Canada. But we have very large deficits with both of them… They are in effect receiving subsidies of hundreds of billions of dollars. We pay subsidies to Canada and to Mexico of hundreds of billions of dollars. And the United States will not be doing that any longer. We are not going to do it any longer.”

It was an excellent speech in terms of the delivery—many US voters will have lapped it up—even if Trump has a tendency to play fast and loose with the truth: at least 26 statements “were untrue, misleading, or lacked context”, not least his claim that the US is subsidising its trading partners by running deficits, which has much more to do with Trump’s “huge federal fiscal deficit” than cheating by trading partners.

So, tariffs are likely to remain a feature of this administration. Trump is no free trader; he’s not using tariffs as a threat to convince other countries to reduce their tariffs. He’s, quite simply, jealous of them:

“If you don’t make your product in America, however, under the Trump administration, you will pay a tariff and in some cases, a rather large one. Other countries have used tariffs against us for decades and now it’s our turn to start using them against those other countries. On average, the European Union, China, Brazil, India, Mexico and Canada — have you heard of them? And countless other nations charge us tremendously higher tariffs than we charge them.

…

This system is not fair to the United States and never was, and so on April 2 — I wanted to make it April 1, but I didn’t want to be accused of April Fools’ Day — it’s not — it’s just one day which costs us a lot of money. But we are going to do it in April. I’m a very superstitious person. April 2, reciprocal tariffs kick in, and whatever they tariff us, other countries, we will tariff them. That’s reciprocal, back and forth.”

This is not a bluff. Worse, Trump doesn’t appear to understand the difference between a tariff and a value-added tax (or GST)—“a VAT tax is a tariff”, according to Trump—despite that claim being palpably false.

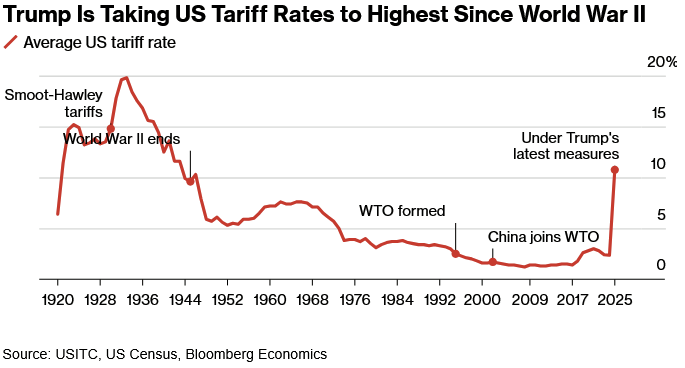

So, the ‘retaliatory’ tariffs coming on 2 April are likely to be large, and will include all of the goods that have already been exempted from the Canada and Mexico tariffs. Expect this chart to continue climbing:

I’m not going to get into the full consequences of the tariffs themselves, except to say that they will drive up prices for American consumers and will decimate certain manufacturers.

The China, Canada, and Mexico tariffs were equivalent to the largest US tax hike since 1993, and will manifest primarily through higher prices: according to Target’s CEO, prices on fruits and vegetables alone are likely to rise because 30% of American consumption comes from Mexico. 85% of America’s potash supply—fertiliser—is imported from Canada, so good luck to US farmers. China’s has also whacked farmers with its own tariffs, which will see competitors “in Brazil and Australia grab market share”.

There’s a reason why, after just one day, US auto manufacturers were grante d a one-month stay of execution, and farmers are crying out for much more than the $30 billion in agricultural subsidies already approved. Expect just about every industry group to do the same, along with households who will soon notice the pinch during their weekly shop.

During the first Trump administration, about half of the thousands of exemption requests were approved. Great for lobbyists and lawyers and the firms they represent, but good luck to small- and medium-sized businesses that don’t have those resources.

Throw in the inevitable retaliation, and it means higher costs for producers in the US and abroad, most of which will flow through to higher prices for consumers—and lower output.

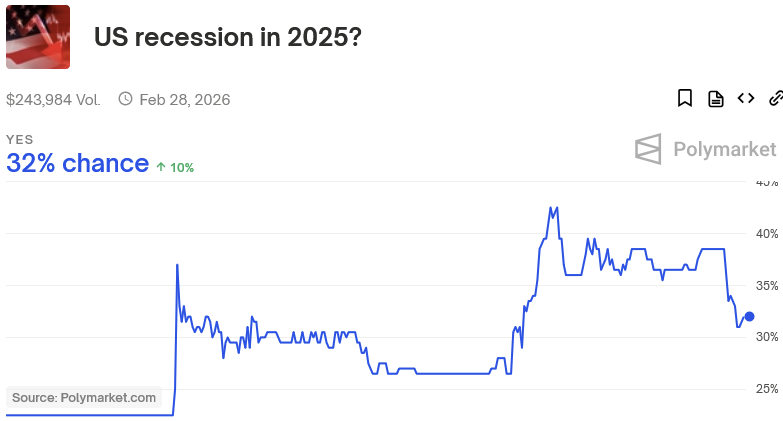

But the real damage is being caused by the uncertainty of it all. No one knows for sure what is going to happen, so many investment and consumption decisions will be postponed or dialled back. US recession prediction markets have see-sawed all over the place this week, reflecting the chaos:

Trump’s ‘retaliatory’ tariffs will be need to be implemented through “a complex labyrinth of different tariffs, which will be hard for the administration to handle and costly for companies to navigate. The reciprocal tariffs in particular [are an] administrative nightmare as they have to be different for each product and for each country… it “will entail elevated and persistent uncertainty as tariff shocks keeps coming (maybe in response to currency moves even).”

The uncertainty of Trump 1.0 reduced investment in the US in a single year by by about 1.5%. By comparison, the uncertainty of Trump 2.0 is off the charts:

According to The Economist:

“Perhaps the biggest surprise of Mr Trump’s presidency so far is his apparent indifference to the downsides of his actions. Investors had thought that he viewed the stockmarket as a scorecard on his presidency. His concern with it has been replaced by a belief that tariffs are obviously good for the economy, since they will revitalise industry and create new government revenues. ‘There will be a little disturbance, but we are OK with that. It won’t be much,’ he said on March 4th.”

No one knows at what level the ‘Trump put’—the point at which Trump will reverse course to correct a sustained downward movement in the stock market—is set this time around. It could be the value of the S&P500 when he won the election (5,800, a level that was breached last night), or it could be a level much lower—perhaps 10% lower than when he was elected, so say 5,200.

Regardless of what it is—or if it even exists this time around—it doesn’t appear that we’re there yet. And even if we were, who’s to say that Trump won’t roll out tariffs again after a stock market rebound? The only certainty is that the uncertainty and chaos will continue to reign, with damaging consequences for the world’s growth prospects.

Trump isn’t bluffing as some part of 4D chess deal to make the world a free trader’s paradise. He truly loves tariffs, and wants to get them up as high as possible without completely destroying the US economy in the process.

Europe goes to war

In the wake of Trump’s abrupt withdrawal of Ukraine-bound military deliveries and critical intelligence sharing, Europe announced that it is rearming itself:

“A five-part plan to bolster Europe’s defence industry and increase its military capability could raise nearly €800bn (£660bn) and help provide urgent military support for Ukraine after the US suspended aid to Kyiv, the head of the European Commission has said.

Ursula von der Leyen said on Tuesday the 27-member bloc would propose giving member states more fiscal space for defence investments, as well as €150bn in loans for those investments, and would also aim to mobilise private capital.”

Germany will remove its debt handbrake to free up “1 trillion euros or more in spending on defence and infrastructure”, while France—the only nuclear power in the European Union— is now “willing to discuss extending the protection afforded by its nuclear arsenal to its European allies”.

I’m of two minds when it comes to the rearmament of Europe. On one hand, there was a good reason why it has been explicit US policy since WWII to prevent European nations from spending too much on their militaries: these are nations have a long, bloody history littered with conflict, both amongst themselves and abroad.

Just because JD Vance’s European history only goes back “30 or 40 years”, doesn’t change that fact. Collective security underwritten by the US was what has enabled peaceful cooperation amongst these warmongering nations.

It’s not inconceivable that in 10 or so years, European nations—which outnumber the US in population by a considerable amount—will have a more powerful military than the US. Might some of them be tempted to use it to settle some old scores? Have you ever watched a sporting event between Serbia and Croatia? They remember.

On the other hand, Russia is a clear and present threat, and if the US has abandoned its role in ensuring peace and security, then Europe has no choice—and for that matter, neither does Australia.

But it won’t be cheap. Despite what politicians are saying about boosting “jobs and growth”, increased military spending is no free lunch; it will involve significant opportunity costs, and will reduce living standards unless it comes from cutting low-productivity spending elsewhere rather than from new taxes or debt, the latter of which also opens a whole other can of fiscal sustainability worms.

In Europe, the obvious choice is trimming the bloated welfare state:

“The rise in social spending over the past century has been uncannily global — encompassing Japan, the US, Australia, Canada — but the absolute levels are highest in Europe. As the most militarily exposed of those places, this isn’t tenable.”

In Australia, it might mean rethinking some of our own ’nice-to-have’ programs that have ballooned in recent years, such as the $50 billion we’re spending each year on the NDIS, the rapid renewable energy transition, or following Europe by spending less on environmental concerns.

The global order is changing, and not for the better. Unpleasant trade-offs are going to have to be made. The world isn’t going to be able to borrow its way out of this one.

The political productivity problem

Former Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) governor, Philip Lowe, pointed the finger squarely at successive governments—state and federal—for Australia’s lack of productivity growth, which has contributed to the current cost of living crisis:

“That’s the source of the cost of living – shall I use the word ‘crisis’? It’s not interest rates. Interest rates have probably suppressed aggregate demand by 1 per cent this year. The lack of productivity growth over that time has suppressed demand now by 9 per cent [today]. So that’s the source of the problem.

And we’ve got to do something about that… We’ve had our living standards rising quickly for decades, and that’s no longer happening, and people are getting unhappy about it. The problem isn’t an economic one, we kind of know broadly what to do. It’s a political one – our society has lost the ability to form coalitions to implement difficult things that in the short run will hurt some people, but are good for our kids. And we’re now seeing the consequences.”

Lowe is broadly correct. With rising productivity, you can paper over a lot of misfortune, including the kind perpetuated by poor fiscal and monetary policy—the latter of which he is at least partially responsible for.

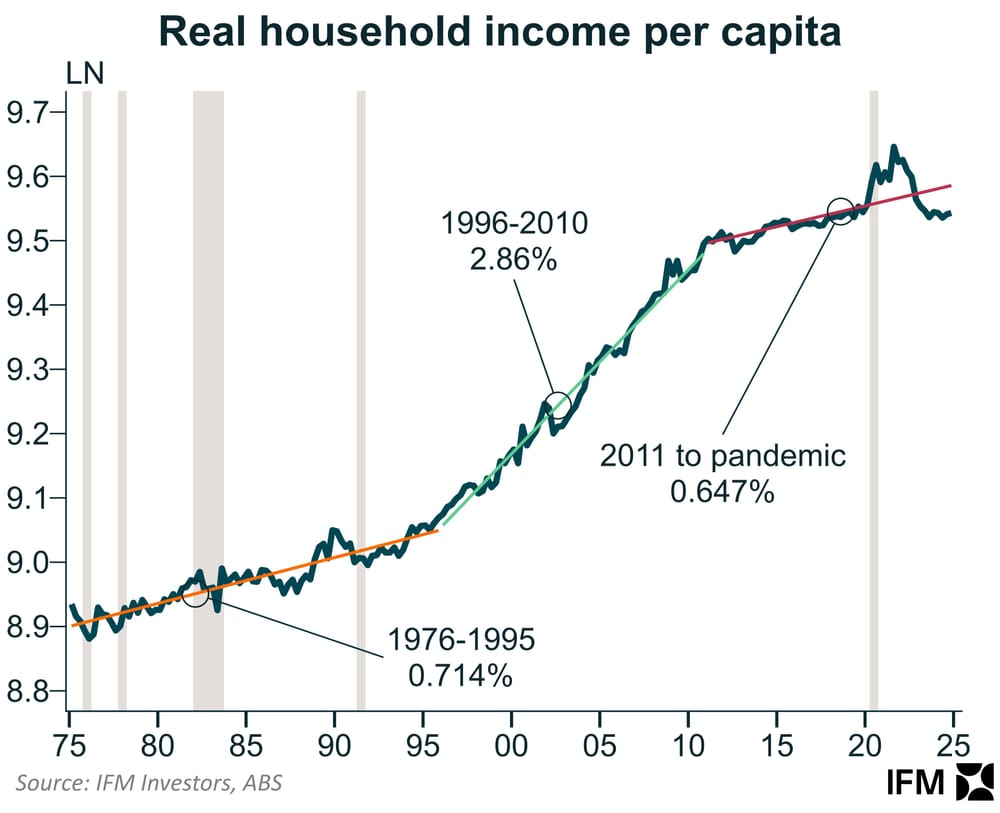

IFM’s Alex Joiner likes to show off the following chart, which shows that lacklustre productivity growth and the ensuing lack of income growth is the norm in Australia, not the exception.

The late 1980s/early 1990s reforms, combined with the emergence of China, saw solid productivity growth and rising living standards between 1996 and 2010. We have since reverted to the mean and are likely to stay there, barring a productivity miracle or concerted effort from all levels of government to boost it—actually now that I think about it, miracle still applies.

One area to boost productivity is in housing, specifically construction. As I wrote the other week, housing construction productivity is being suffocated by burdensome land-use zoning laws, building regulations, and meddlesome local governments.

AustralianSuper’s chief executive Paul Schroder recently observed that expensive housing due to our inability to build and keep prices down was sucking productive resources from the rest of the economy, until “everything feels like a drag”:

“We need to just get housing going as much as we can. In the [US], the total housing is $US50 trillion against an economy of $US29 trillion. In Australia, because we have ploughed so much into our houses… it is worth $11 trillion versus GDP of $3 trillion.

We have poured all this money into houses – all very well and terrific, we’ve painted the front fence and sold it on – which has deprived the economy of heaps and heaps of productive capital. We have all this money in our domestic houses, and we’re not backing businesses.

We are not creating new things, and we are not driving productivity.”

The end of the mining investment boom—which raised the level of productivity, but has since stopped increasing the rate of growth—and the lack of meaningful reform (which contributes to the large relative share of unproductive housing) is a key reason why Australia is stuck in a productivity quagmire. Real incomes will stagnate until something is done about it.

Fun fact

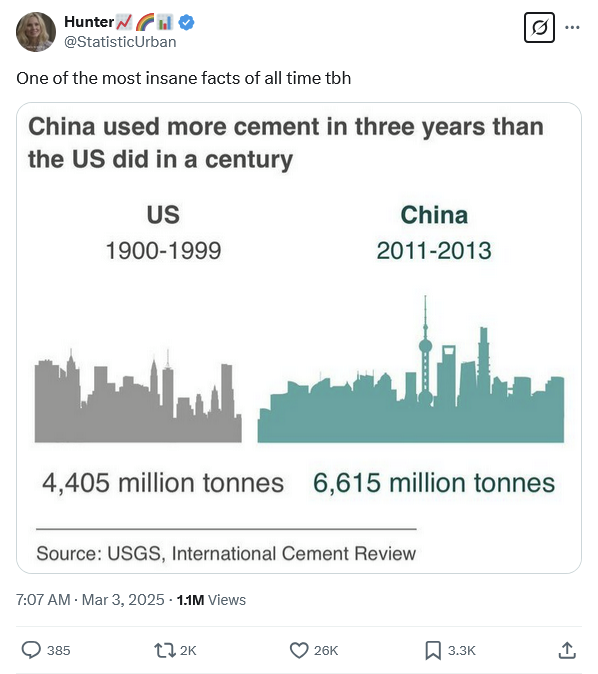

China builds a lot of stuff.

Further reading

- A real-time Trump 2.0 trade war tracker.

- Germany’s recent election might “cement a role for nuclear energy in a raft of upcoming [EU] legislation”.

- Nuclear power is back on the menu in Italy for the first time since 1990, with a new bill “to provide a legal framework for the construction of future nuclear power plants”.

- Norway embraces trade-offs, putting “societal benefit” ahead of the environment: “The bill allows [hydro] power plants bigger than 1MW to be built in protected waterways if the societal benefit is ‘significant’ and the environmental consequences ‘acceptable’.”

- New Zealand’s economy was the worst performing in the developed world last year and its central bank chair abruptly resigned on Wednesday after a controversial tenure during which he was accused of bullying, tripling staff numbers, and redirecting the bank’s core focus away from inflation and towards issues like Te Ao Maori and climate change.

- How the British broke themselves: “Decades-old rules make it too easy for the state to block housing developments or for frivolous lawsuits to freeze out energy and infrastructure investment.”

- The AI uptake might be slow: “[H]ighly inefficient, governmental or government-subsidised sectors… just won’t adopt AI, or use it effectively, all that quickly.”

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!