The high cost of Xi's vision for China

I’ve held off writing about China’s third plenum because the whole process is very secretive and I wanted to allow time for everything that was going to be revealed… well, to be revealed! That looks to have now happened, with over 22,000 Chinese characters (~17,000 words in English) released in a statement to the public. Although as is all too common with China, by one account it’s not much more than a masterful effort at using a lot of words to say very little of substance at all:

“It fixates on what Beijing wants to happen without explaining how it will do it. The package is not coherent. It also doubles down on policies raising alarm bells globally about China’s growth model and persistent macroeconomic imbalances.”

Yep, so more state-directed investment – “new productive forces” – that will create even more overcapacity in favoured sectors, riling up the governments of an increasingly protectionist world. According to The Economist:

“Of its 60 sections, three are devoted to innovation, including one on ’talent’. A fourth discusses ’new productive forces’, the economic buzzword of the past ten months, which refers to technology-driven leaps in productivity.

This emphasis reflects Mr Xi’s belief that the world is in the midst of a scientific revolution that China should lead. But it also betrays Mr Xi’s siege mentality. He is determined to break America’s stranglehold on key technological inputs, such as high-end semiconductors. In 2013 the plenum resolution allocated three sections to national security and military reform. This one devotes seven, including a commitment to counter foreign sanctions.”

China’s problems are today almost entirely self-inflicted, the result of past attempts at state-led industry. Before solar, batteries, electric vehicles and semiconductors it was the likes of property, steel and energy. The result was overcapacity, with China forced to export its surplus.

Investment is important, to be sure – it’s crucial to increase the amount of capital per worker, boosting productivity, real wages and then consumption – but investment in China is so often misallocated that it does very little to contribute to the goal of becoming a wealthy nation.

President Xi Jinping appears not to have learnt from the mistakes of the past. Or if he has, he has learnt the wrong lessons.

Decades of unproductive growth

Before getting into just where Xi has gone wrong, China’s current problems are not all due to his management. Here’s a quote from Elizabeth Economy’s 2018 book on China, The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State:

“Investment-led growth was taking its toll, contributing to skyrocketing levels of public and corporate debt. And for all its impressive economic gains in low-cost manufacturing, China had little to show in the way of innovation or the development of the service sector, the markers of the world’s advanced economies. By the time of Xi’s ascension to the top job, despite a number of noteworthy economic and foreign policy achievements, the Hu Jintao era had become known as the ’lost decade.’ Xi Jinping took power determined to change China’s course.”

Research suggests that up to 75% of Chinese growth between 1978-2007, i.e. the reform period, was due to total factor productivity (TFP) growth. For those not familiar with the productivity literature, that’s basically how much output can be produced with a given amount of labour and capital. China was of course adding more of both due to a positive demographic dividend and foreign investment, but it was also using it more efficiently.

That was a huge change from Mao’s leadership, where TFP growth was likely negative, perhaps because he had a penchant for sending intellectuals to toil in the fields, and encouraged people to create pig iron by melting their farming tools in backyard furnaces.

But since 2007, TFP growth in China has been very slow; even below levels experienced in advanced economies such as the US, likely due to diminishing returns on its investments in residential property and infrastructure. So, the rot started well before Xi, who wasn’t ’elected’ until 2013. But he has done very little to stop it.

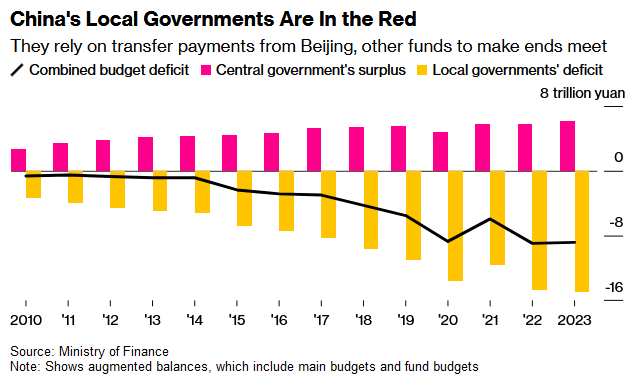

The fiscal structure of China’s government is also responsible for a lot of its problems. Basically, the central government enacts unfunded mandates, “implicitly pressuring local authorities to borrow to provide for these mandates”. With just over 50% of revenue raised locally but nearly 90% of total expenditure done at that level, local governments are forced to borrow to make up the difference:

Local governments are also limited in how they raise revenue. Most comes from land sales, incentivising them to push real estate and all the infrastructure that goes with it:

That worked for a while, with revenue from land sales papering over large losses in everything else (e.g., bridges to nowhere; underutilised rail lines; and fleets of empty buses):

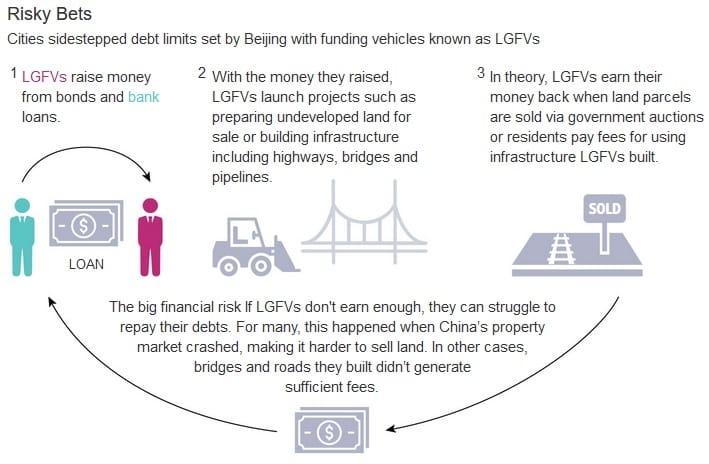

“For years, Liuzhou and scores of other Chinese cities together amassed trillions of dollars in off-the-books debt for economic development projects. The opaque financing was the yeast that helped China rise to the envy of the world.

Today, overgrown construction sites, sparsely used highways and abandoned tourist attractions make much of that debt-fueled growth look illusory and suggests China’s future is far from assured.”

Chinese people also had few places where they could save, so they piled much of it into real estate. As a result, China has trillions of dollars sunk in unproductive ghost cities and wasteful investments.

Enter China’s chief economist

Perhaps because of his Marxist upbringing, or that he rose through the party ranks during the post-Mao reform period, Xi came to believe that the solution to those problems was not to continue liberalising while also fixing structural issues such as China’s broken fiscal model, but to reverse course; to instil a bit of Maoist thinking back into the country. Here is Elizabeth Economy again:

“The ultimate objective of Xi’s revolution is his Chinese Dream—the rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation. As noted earlier, however, Xi’s predecessors shared this goal as well. What makes Xi’s revolution distinctive is the strategy he has pursued: the dramatic centralisation of authority under his personal leadership; the intensified penetration of society by the state; the creation of a virtual wall of regulations and restrictions that more tightly controls the flow of ideas, culture, and capital into and out of the country; and the significant projection of Chinese power. It represents a reassertion of the state in Chinese political and economic life at home, and a more ambitious and expansive role for China abroad.”

Neil Thomas, a fellow for Chinese politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Centre for China Analysis, believes that Xi still holds those views:

“Xi is focused on securing China’s supply chains and growth potential amid rising political and trade tensions with the US and the European Union. By aiming to lead in electric cars and artificial intelligence, China aims to boost its self-sufficiency, particularly as America seeks to limit its access to advanced chips.

Xi also believes that the policies pushed by pro-market voices in the past led to many of the problems he inherited when he came to power in 2012, such as years of debt-driven growth.”

Since the retirement and sudden death of former Premier Li Keqiang, who was seemingly the lone reformer in the administration, Xi has drifted even further towards state-led development. Stephen Roach, former Morgan Stanley Asia chairman, recently declared that Xi had made himself the country’s ‘chief economist’, with “economic decisions becoming more centralised and less open to debate”.

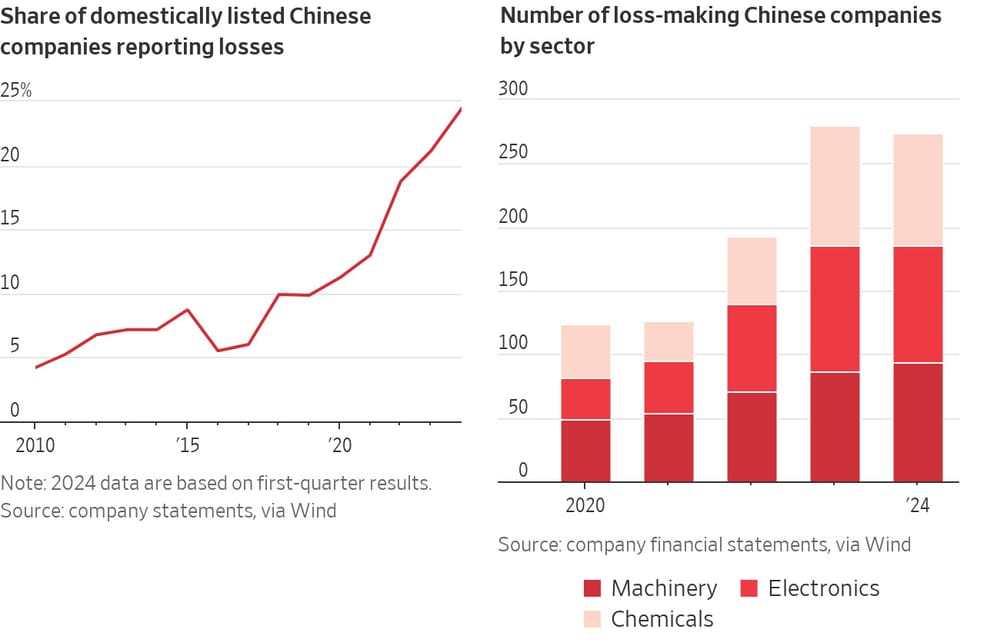

Now, instead of piling into real estate, local government officials are channelling resources into “industries seen as favoured by the central government (such as EVs and solar) as a sign of loyalty”, but:

“If China’s local government resources are all chasing the same favoured industries and none wants to appear disloyal or ineffective by lacking a local champion, overcapacity could worsen. Senior Chinese officials have acknowledged the problem of excessive local EV production aided by local governments, but progress to curtail this overproduction is not yet visible.”

And it hasn’t worked out all that well.

Xi’s “Four Nos”

Under Xi, China’s actual growth rate may have been as low as 1-2% last year. According to Scott Kennedy, there are four possible reasons – “The Four Nos” – as to why Xi has failed to right the economy over the past decade:

- “He doesn’t know”: An unintended consequence of the ‘corruption purge’, i.e., the elimination of all political rivals, means that Xi has surrounded himself with yes-men who fear delivering bad news.

- “He doesn’t know what to do”: There’s no ‘right’ play book here, and the one Xi is reading from probably isn’t helping him.

- “He doesn’t care”: Xi’s top priority is likely strengthening his, and the Communist Party’s, hold on power, rather than fixing economic issues.

- “He doesn’t agree”: Xi may disagree with critics and is legitimately of the belief that prioritising sectors like electric vehicles and semiconductors, giving him leverage over global supply chains, is the correct approach.

Kennedy believes that most people put it down to #4: that Xi honestly believes in the merits of industrial policy, and that in time it will pay off. Being an economist who believes that incentives shape outcomes, I think it’s more likely that #3 dominates, although no doubt all four play some part.

You need to remember the Chinese economy, despite being ‘run’ by a guy who is effectively a dictator, is not immune to rent seeking – the act of seeking benefits at the expense of everyone else. If anything, the huge amount of power concentrated in the state leaves China more vulnerable than western nations because the rewards are that much greater. Corruption is rife, and powerful constituencies that benefit from the current model repeatedly lobby to prevent change. So while everyone knows that “structural reform” is what’s needed, when the incentives push everything in the other direction, in practice that’s hard to achieve.

So, perhaps the only positive outcome of the third plenum was a commitment to trying to reduce China’s reliance on local governments:

“Over the next five years, China will aim for a ‘clear division of responsibilities, coordinated financial resources and regional balance’ in the fiscal relationship between central and local governments.”

Whether Xi achieves that – there are many, at all levels of government, who benefit from the current model – is another question entirely. In the meantime, even if Xi succeeds at propelling specific industries to global competitiveness, it will come at significant cost. Again, here’s Economy writing back in 2018; it’s amazing how little has changed:

“China’s deep pockets combined with its ability to limit foreign competition mean that it has the wherewithal to forge ahead despite the waste, inefficiency, and seeming weaknesses in innovative capacity.

…

Even in the face of poor initial performance of Chinese indigenous technology and weak acceptance of it in the Chinese market, the government persists. Beijing’s willingness to accept suboptimal technological outcomes in order for Chinese firms to capture the market—as in the case of battery technologies—leads to significant waste of resources and inefficiencies.

…

Underpinning much of the challenge in both China’s SOE reform and the innovation sector, therefore, is a reluctance on the part of the Chinese leadership to relax the reins of state control and to allow the market to serve as a disciplining agent—helping to separate the best ideas from the weaker ones and the better companies from the poorer ones. The government is willing to tolerate a higher level of waste and inefficiency in the cause of capturing market share and fulfilling other developmental and strategic objectives.

In other words,the state pumps considerable sums of money into its effort to becoming a global leader in things like solar panels and EVs, at the expense of the rest of its economy:

Resources are scarce: every yuan pumped into developing solar or EVs involves a trade-off; some other productive activity that is discouraged because of that decision. Moreover, because the government has sunk so many resources into such sectors – beyond what China and the rest of the world appear capable of absorbing – it’s having to ‘dump’ them, often at a loss (if the loss from selling overseas is smaller than the loss from selling domestically, the product will still be exported).

The rest of the world benefits from these cheap goods at the expense of Chinese households, but the long-term political sustainability of such a model is dubious.

The mistakes go beyond EVs

Who could forget the now-forgotten Belt and Road, which is more of a noose around the necks of those countries that signed up to it than a legitimate path to economic development. Much of the capital China invested on those projects has almost certainly been wasted.

But Xi also messed up China’s human capital. Wanting to delay people’s entry into the labour force following the Great Recession, China’s leadership (admittedly, pre-Xi) rapidly expanded the country’s higher education sector. The country is now setting graduation records, but youth unemployment is in the double-digits because graduates’ skills aren’t useful to employers:

“The rising number of graduates might not be such a problem if they were learning skills desired by employers. But Chinese companies complain that they cannot find qualified candidates for their open positions. Part of the problem are low-quality minban daxue. Yet the skills mismatch extends across higher education. For example, the number of students studying the humanities is growing even though demand for such graduates is much lower than that for specialists in other fields.

…

Unable to find work befitting their degrees, a number of graduates are settling for low-skilled jobs, such as delivering food. Last year a memo from an airport in Wenzhou noted that it had hired architects and engineers to be its groundskeepers and bird-control personnel.”

A similar effect happened in innovation. Xi wanted China to lead the “new productive frontiers”, but his approach got the incentives wrong:

“Innovation is also impeded by the Chinese government’s reliance on top-down campaigns to achieve markers of innovation, without necessarily paying enough attention to the actual content. Beijing set a national goal for 2 million patents by 2015, for example, and surpassed it ahead of schedule. But in 2014, more than 60 percent of patent applications were ‘utility and design’ patents that ’typically do not represent significant innovation’.”

I’m reminded of the Soviet economy, where a famous “cartoon depicted the manager of a nail factory being given the Order of Lenin for exceeding his tonnage. Two giant cranes were pictured holding up one giant nail”.

Xi’s vision for China and his “new productive forces” have many parallels with the Soviet economy. In the book Building a Ruin: The Cold War Politics of Soviet Economic Reform, Yakov Feygin documents Leonid Brezhnev’s attempt at a “scientific-technical revolution”:

“The revolution, with its accompanying technologies – most important, computing and the automation of production – was a global process. Only the Soviet Union, however, was politically organised along ‘scientific’ lines and did not suffer from capitalist ’economic contradictions’, so it alone could fully take advantage of the changes coming. The doctrine of the scientific-technical revolution also implied that the fundamental relationships of the Soviet economy did not need changing. Only new techniques of organisation needed to be introduced.”

I imagine that Xi’s state-led innovation experiment will end in similar fashion.

China’s loss is Australia’s gain

While it would be better for Australia and the world if China had actually liberalised and got rich, we still benefit in two ways from Xi’s approach to economic development.

One, we get cheaper products, such as EVs, solar panels and batteries. Those alone will probably help us decarbonise more than any Australian government policy has managed. They’re essentially subsidies, paid by the Chinese, to Australian consumers and businesses, who are then free to allocate resources to more productive endeavours where we have a comparative advantage.

Two, China is probably going to keep importing Australia iron ore and other commodities, at least while Xi’s policy persists. Its population might have peaked, but many of its buildings are old, or are in cities such as Liuzhou where they’re not needed rather than in so-called Tier 1 cities. It also needs plenty of steel and commodities in the manufacturing and infrastructure sectors that Xi wants to expand, so even if property demand will fall from here, it will be a slow fall.

In fact, one reason why China still buys so much Australian iron ore is because of a another previous mistake. Instead of using more scrap steel in electric arc furnaces, a natural path trodden by other economies as they developed, the Chinese state directed people to build so much coal-fired blast furnace capacity that it’s still a lot cheaper to smelt Australian iron ore into new steel than to recycle old steel. As steel prices have eased with the property slump, the pressure on the less profitable electric arc method has only intensified, improving the competitiveness of those blast furnaces, raising iron ore demand and prices.

That could, of course, change. But such as shift is unlikely to happen under Xi’s watch, which due to his power grab will now extend until he dies or is forcibly retired. In the meantime, China’s economy will slow, true innovation will be stifled, and resources will be wasted.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!