The high price of Australia's policy shortcuts

This post follows from Tuesday’s essay on Australia’s temporary fiscal surplus and the misguided government spending that may well leave the country mired in a decade of deficits.

I’m going to build on that theme today, starting with the Labor government’s seeming obsession with cheap gimmicks instead of meaningful reform, perhaps none as blatant as Anthony Albanese’s (Albo) recent focus on chips. Not the silicon type that everyone from China to the US is racing to build; we’re far too sophisticated for that!

No, I’m talking about potato chips. Believe it or not, but this was in a real tweet sent by the Prime Minister of Australia:

It would be funny if it weren’t so sad. To stop potato chip makers from allegedly “ripping Australians off” by putting too much air in a bag, Albo wants to roll out “stronger unit pricing”, which sounds nice except that, as the helpful community note slapped on his tweet noted, we already have pretty good unit pricing in Australia:

“Unit pricing is already mandatory under the ACCC code since 2010. It does nothing to address high prices, shrinkflation or transparency.”

As for whether “shrinkflation” is obscuring the true amount of measured inflation, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) already makes adjustments for changes in quality and size:

“The use of transactions ‘scanner’ data in the Australian CPI, which provides detailed item information, enables the ABS to identify and adjust for quality change arising from shrinkflation.”

I was hopeful that this Labor government, having learnt its lessons from the failed Bill Shorten campaigns in 2013 and 2016 and the chaos that was the Morrison government, would bring some much-needed common sense to policy-making. It pledged to be transparent; to be everything that the previous government was not.

But alas, what we have a government that is somehow “more secretive” than its predecessor and appears content with symbolism over substance.

Productivity, not potatoes, are the key

The third and final piece of analysis last week was a report from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), titled: Productivity in the post-pandemic world.

Quite relevant for a country in the middle of a productivity crisis!

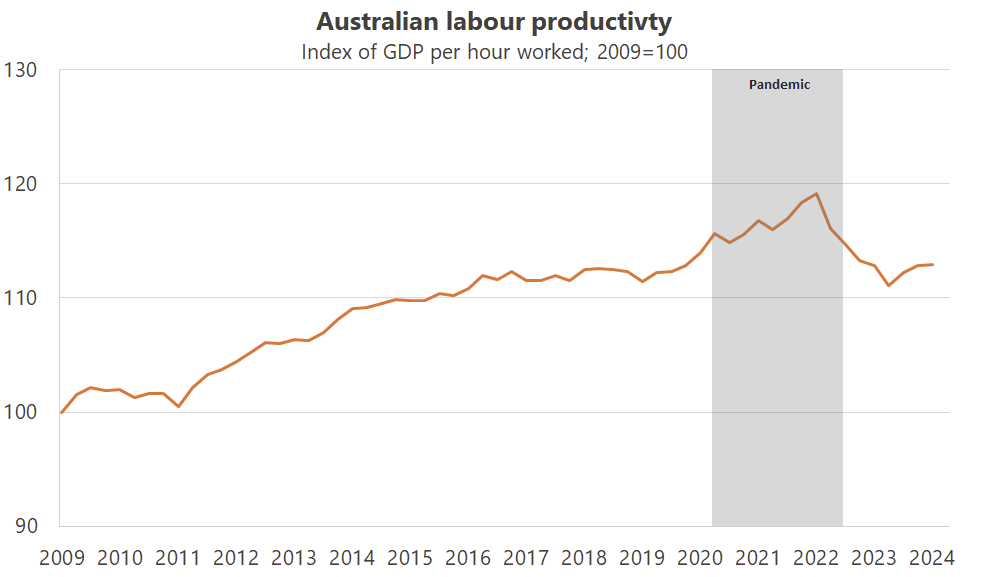

The report noted that the ‘bump’ in productivity during the pandemic was likely due to the move “away from lower-productivity contact-intensive services such as hospitality”. You can clearly see it in Australia’s measured productivity:

But consumer preferences didn’t really change, so when the restrictions on activity went away, so too did the temporary spurt of productivity.

Except in the US, where productivity growth continued in part due to “strong investment, in turn linked to business dynamism, along with greater labour market flexibility”.

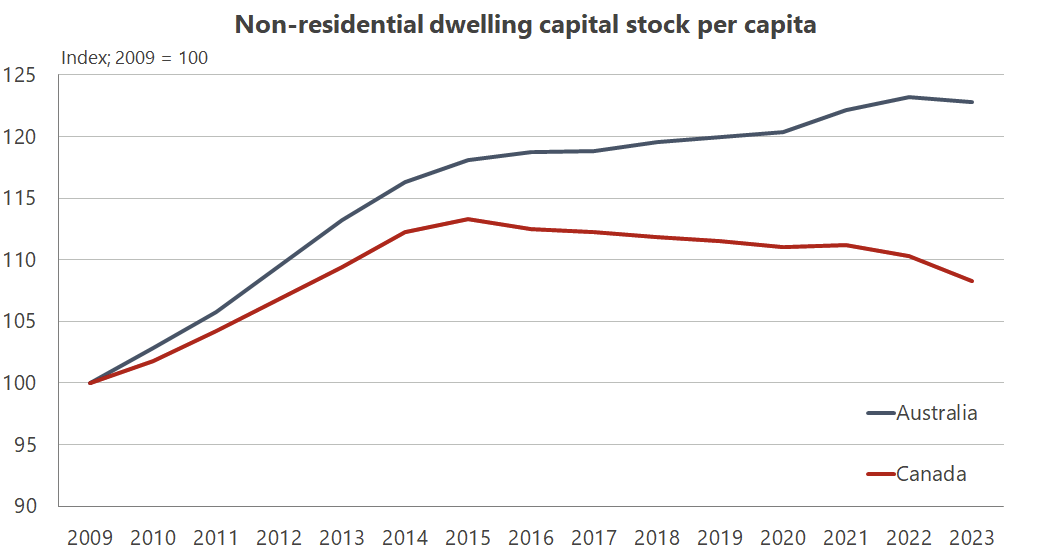

As for Australia, we were not so fortunate. In fact, we experienced “capital shallowing”, because “the investment response in Canada and Australia has lagged growth in the labour force”.

Regular readers will know that my analysis of the Canadian economy found the same problem had been plaguing that economy for years, with Canada’s capital stock per worker falling from around 2015. In it, I warned that the 2023 fall in Australia – the first decline since at least 1970 – was “a bad omen for the future”. Here’s the chart:

Well, the future is here:

“Lost schooling during the acute phase of the pandemic may erode skills in the decade or so ahead. This compounds the challenges from ageing, with the working-age population projected to decline materially in several European and Asian economies. While the pandemic also triggered a rapid expansion of digitalisation, with the potential to raise productivity to varying degrees across countries, empirical estimates of the actual impact of the expansion have been mixed.”

Going forward, the BIS worries about “weak investment, ageing, [and] trade fragmentation”. To alleviate the impact of those possible negative shocks, governments should get moving on structural reform, especially “measures to introduce more flexibility” that will help to improve technological diffusion.

But those are areas where this government may have already done more harm than good, most notably with its industrial relations reforms. According to research by the e61 Institute:

“Firms don’t just cop higher labour adjustment costs. They seek out more flexible inputs – whether that’s casual workers or capital – and this generates winners and losers. This suggests that the government should think carefully about all the ways firms could adjust to their proposed ‘same job, same pay’ regime.

…

Some level of job protection is necessary to ensure firms internalise part of the social cost of dismissals. But protections run counter to the policy principle of ‘protecting workers, not jobs,’ raising questions about whether we have struck the right balance.”

If you seek to protect jobs, you reduce mobility and business dynamism – how firms grow and the ability of workers to move between them – both of which are key to productivity growth and the creation of new jobs. If policymakers get the balance wrong, resources will struggle to flow to their most productive uses, ultimately reducing productivity, growth and real wages in the long-run.

Stop making it worse

The latest Ipsos survey of Australians found that the Labor government “face[s] challenges left and right”:

“On the right, while the ALP lead on Healthcare alone, the Coalition lead on four issues: Cost of Living, Housing, The Economy and Crime. On the left, the ALP have lost ground to the Greens on Housing since the last election.”

What do people care most about? The cost of living and housing:

I’d almost argue that “The Economy” and “Cost of Living” should be combined, given how interrelated they are. Inflation is clearly the issue right now and should be prioritised over everything else.

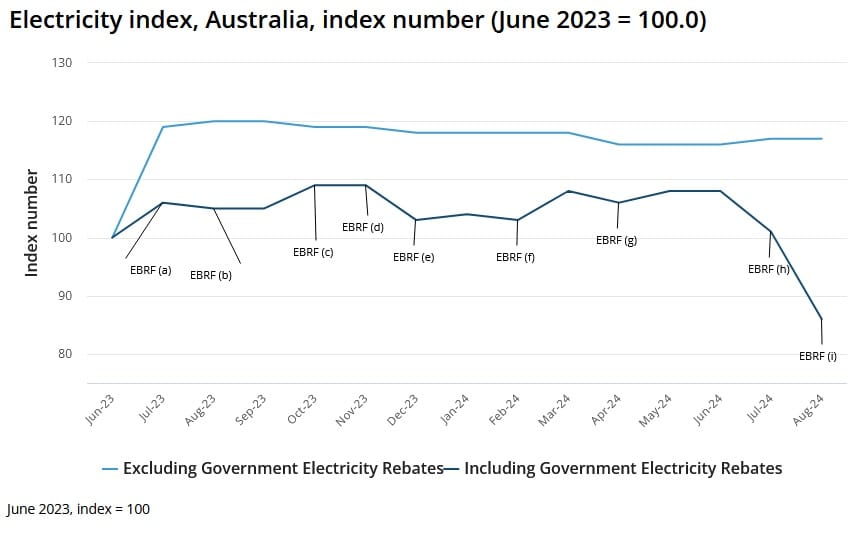

So, what has the government done about it? Not much: basically, just energy subsidies and cash handouts. Yes, those will put a bit of cash back in people’s pockets. But they’re not targeted, add to aggregate demand and distort prices, worsening the very problem the government is claiming to address.

To the extent that they lower consumer prices, it’s only temporary and the RBA is well aware that it’s being played:

But perhaps the worst part about the subsidies and handouts is they create the incentive for their own continuation: no government wants to be the one to raise prices on people, so they’ll just keep the distortion going by rolling them over forever.

That’s surely a key reason why the Queensland opposition pledged to maintain the recent 50c fare cap on public transport. But Queenslanders will still pay just as much for transport and electricity (probably more, because there’s less of an incentive to economise on usage), they’ll just do it indirectly via higher taxes instead of direct user charges, with a deadweight loss tacked on because it’s less efficient.

As for housing, the federal Labor government plans to reintroduce its Help to Buy scheme to the House of Representatives this week, despite evidence from the UK – which tried its own version with exactly the same name – that it will fail to improve affordability. And as the Greens have pointed out, even if it does have some take-up, it won’t even help the very people Labor claims it will.

I also worry about the implicit marginal tax burden Help to Buy might impose on recipients: yet another welfare scheme linked to a fixed income threshold that will reduce their incentive to ever skill up, or work enough, to move beyond that threshold. Inefficiencies everywhere!

Lots of policies, no solutions

As I’ve written many times before, none of the Labor government’s – or a future Coalition government’s – policies look as if they will help address the actual reasons housing is expensive. So, barring a drastic change in policy approach, that basically leaves housing out of their hands: it’s up to state governments to sort it out.

Unfortunately, with a federal election due in the next several months, the current government appears to be all out of political ideas and capital (just look at the Senate backlog). But if a future government wanted to reduce the cost of living for households, it would follow the very clear advice that its economists have no doubt been offering: allow more supply, and stop inflating demand.

For demand, cut spending and pay off debt, so that when the situation gets truly bad you can afford to help people in a targeted fashion, while also cutting taxes to get the economy rolling again.

As for supply, stop crowding out the private sector with massive government make-work schemes like the NDIS and many of the major infrastructure projects (save those for when we’re not at full employment!), and abandon foolish endeavours like a Future Made in Australia.

Every dollar spent on those programs has an opportunity cost, pulling resources away from, and driving up costs for, the rest of the economy that’s trying to produce goods and services that consumers actually want. Manufacturing jobs (pun intended) with industrial policy will create work, to be sure, but it’s not going to create growth because of the “deeply rooted forces” that caused us to move away from manufacturing in the first place.

The focus should be on connecting workers to the jobs of the future. In Australia, that’s not manufacturing, and no number of subsidies will change that fact.

Finally, the government should actively seek to remove red tape and regulations so that we can build. Not just houses, but also the energy infrastructure that will inevitably be needed to power the industries of the future and make Australia an attractive destination for investments other than those that just dig stuff up.

Voters are good at seeing through gimmicks; just ask Queensland Premier Steven Miles, who may lose his own seat in the upcoming state election despite promising voters everything under the sun. If the Albanese Labor government doesn’t get serious about producing solutions – and soon – then it may not even get a second term, let alone a third.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!