The Kiwi in the coal mine

It’s ANZAC day tomorrow, so in honour of our Kiwi friends I thought I’d take a quick look across the ditch and see how New Zealand’s economy is faring. And let me tell you, if you thought the Australian economy was in for a rough patch, it could be a lot worse!

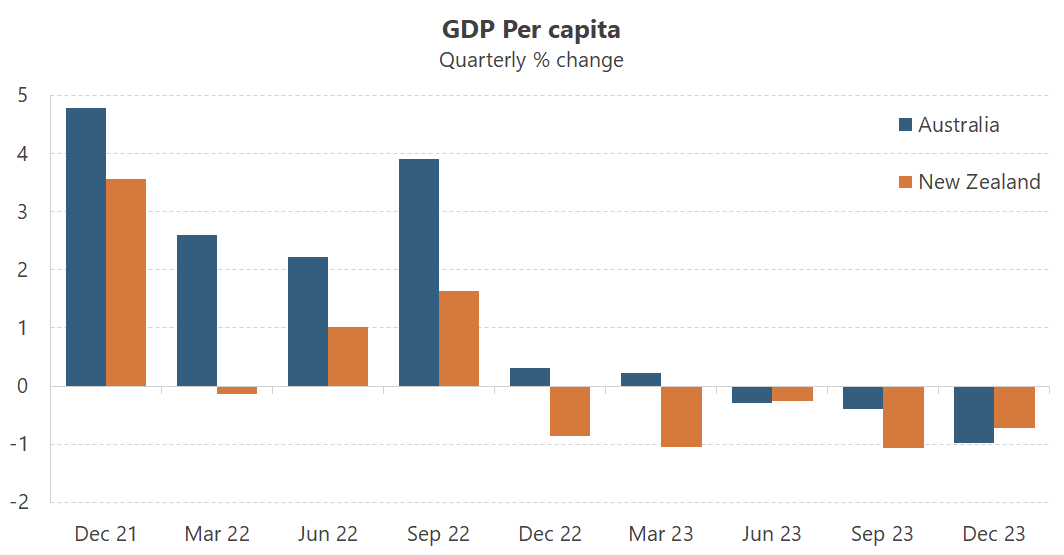

For decades, the once-vaunted New Zealand economy has been falling behind other advanced economies on several key indicators. It’s currently in its second technical recession in the past 18 months (defined as two consecutive quarterly contractions), and perhaps even more worryingly on a per capita basis has been shrinking for five consecutive quarters. By contrast, Australia has ‘only’ contracted for three consecutive quarters (woohoo!). Seriously though, we have nothing to boast about; for the past two years we’ve barely had any per capita growth and in the most recent quarter we actually underperformed the Kiwis.

How did it all go so wrong?

Once at the frontier of global productivity following an ambitious reform agenda in the 1980s, the Kiwis now languish towards the back of the advanced economy pack, which has contributed “to a rapid increase in unit labour costs, undermining New Zealand’s competitiveness”.

That’s perhaps best epitomised by the fact that the Kiwis recently scrapped their Productivity Commission, which had disintegrated from the inside with the appointment of commissioners who were “not at all actually focused on or expert in productivity”. New Prime Minister Christopher Luxon laid out the dire situation with a comparison to Eastern Bloc countries and, of course, Australia:

“New Zealand’s economy is now less productive than vast swathes of the former Eastern Bloc, including Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia and Lithuania … The median full-time worker in Australia now earns $20,000 more a year than someone in New Zealand.”

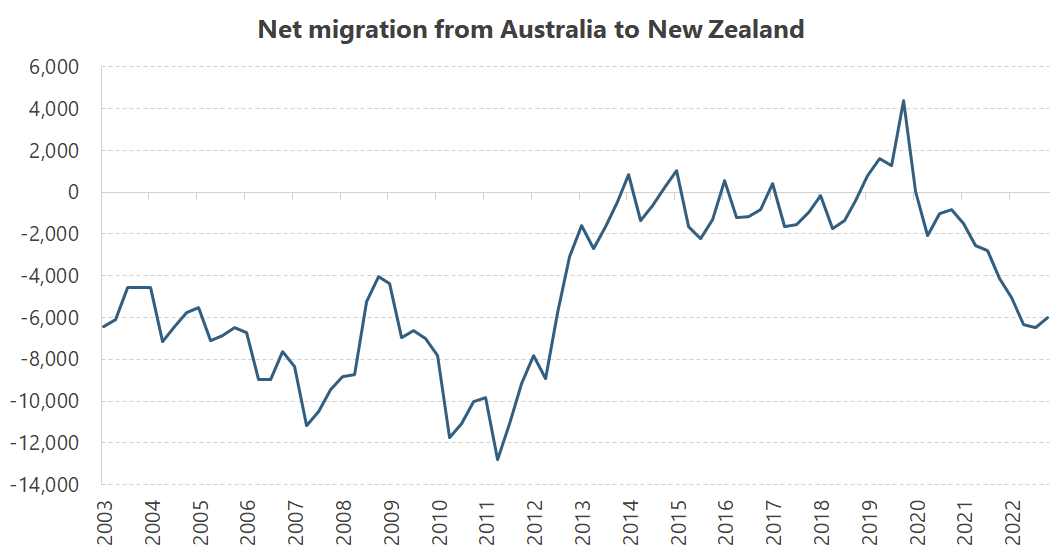

That wage differential and the fact that Kiwis can work freely in Australia has led to an “emigration of skilled New Zealanders”. The brain drain slowed when the mining investment boom dried up and actually reversed during the pandemic, but since then it has once again deteriorated.

What led to the New Zealand productivity decline? Most advanced economies have experienced a productivity slowdown, but the Kiwis have done especially poorly. According to former RBNZ, Treasury and IMF economist Michael Reddell, that’s partly because neither major political party has had much interest in productivity other than when it makes for a good headline:

“I was an enthusiast early on for the idea of the creation of a Productivity Commission in New Zealand. It was one of the recommendations of the 2025 Taskforce report in 2009 and was also a bit [of a] cheap gift to the ACT party, then supporting National in government. Supporters tended to look across the Tasman at the contribution the Australian Productivity Commission had made to enriching policy research and analysis there.

…

But I was also fairly sceptical from early on as to just how long the new New Zealand Productivity Commission would last. That wasn’t because I expected them to do bad work or even fail to contribute to the New Zealand debate (and our aggregate productivity performance was dire and longstanding). It was more the track record: the Monetary and Economic Council had come and gone, as had the Planning Council. Both had at times produced useful papers, but that hadn’t saved them. It wasn’t clear what was likely to be different about the Productivity Commission over the medium term, whether what saw them off was getting offside with the government of the day, fiscal stringency, lack of critical mass or whatever. There wasn’t, after all, any sign of a passionate embrace by either main political party of the cause of markedly lifting New Zealand’s productivity growth.”

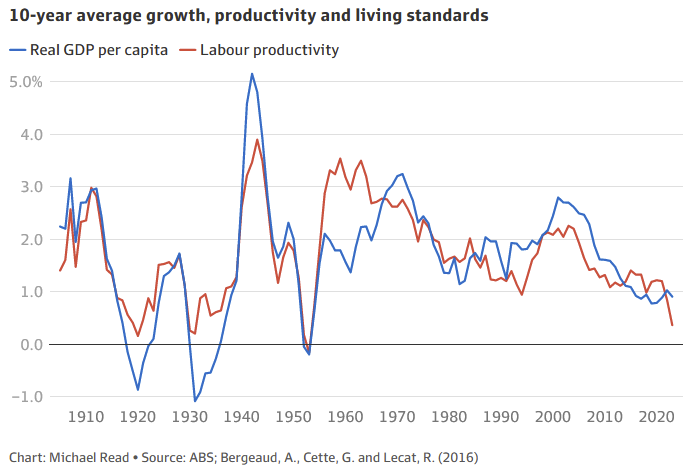

Between 1996 and 2023, labour productivity in New Zealand grew at just 1.2% a year versus 1.8% in Australia. Good for us, right? Sure, but you must remember that while we both passed important productivity-boosting reforms in the 1980s and then did very little on that front for decades (and counting), we also happened to have a mining boom during those years; the Kiwis were not so fortunate.

That’s a key the reason for the difference between the two countries: Australia experienced much greater levels of capital investment than did New Zealand. An interesting new report from NAB found that “in the decade before the pandemic, about 70 per cent of the [Australian productivity] gains came from the fruits of the mining investment boom, which was unlikely to be repeated”.

Productivity growth in both Australia and New Zealand is now in the gutter (negative in both countries in 2023), and our policymakers won’t have another mining boom to rescue us this time. If we don’t get meaningful productivity-boosting reform soon, then we’re destined to end up like the Kiwis:

“Australians will experience an even slower improvement in real wages in the years ahead than was forecast in last year’s Intergenerational Report”.

I think it’s worth reminding ourselves that growth and prosperity are not guaranteed; in fact, the default human state is the opposite of that: poverty. Economic policy is all about trade-offs, and it may be that we, as a society, choose more equity in exchange for less efficiency. But if we get the balance wrong and undermine important institutions in the process, in the long run we may end up with less equity and efficiency.

Which brings me to Jacinda Ardern.

Ardern’s lasting legacy (feat. Chris Hipkins)

When Labour’s Jacinda Ardern was elected in 2017 on the back of an unexpected, unholy alliance with the nationalist/populist New Zealand First Party, she promised that her government would be “active… focused, empathetic and strong”.

Ardern was certainly empathetic, winning global plaudits for her response to the mass mosque shooting in 2019, and for being “the antidote to Donald Trump”. Now retired, she holds two separate fellowships at Harvard University and gives regular speeches on topics such as “democracy, disinformation and kindness”.

But history will not view Ardern’s economic legacy all that kindly. In 2017, New Zealand’s economy was humming along with annual real growth of around 3.5%. That continued until the pandemic, which saw lockdowns and the closure of the country’s borders for more than two years. But it takes time to write and pass economic policy, and the Ardern government was certainly keeping itself “active” in making structural changes to New Zealand’s economy. Those changes were disproportionately focused on equity, with efficiency and productivity given the cold shoulder.

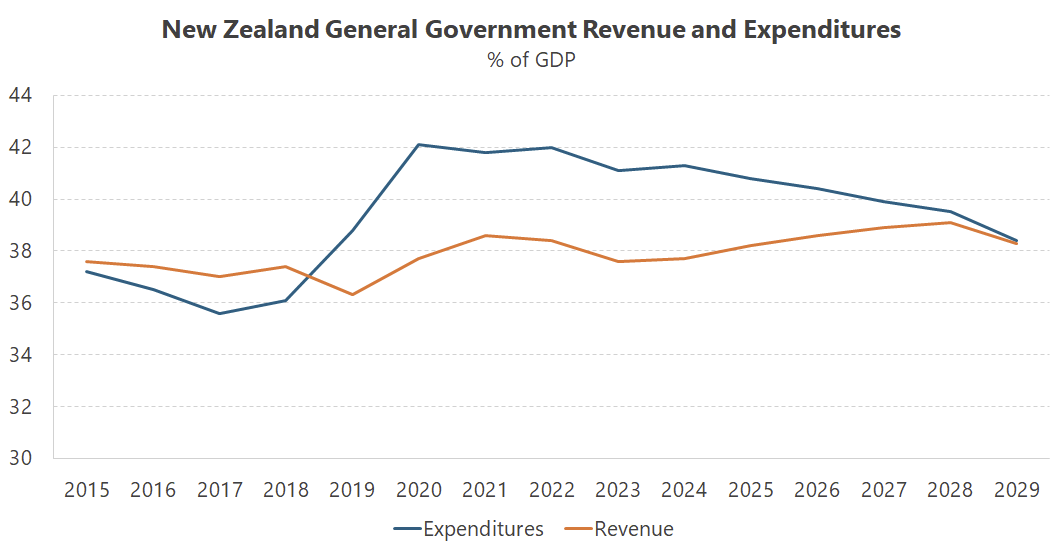

The difference was paid for with debt, which is perhaps the most economically important legacy of the Ardern government: a large structural fiscal deficit that will be politically challenging to unwind. The fiscal impulse in New Zealand is still “more expansionary than in most other advanced economies”, and its “debt increased more rapidly than in many advanced economies in recent years”.

That really just serves to highlight how poorly their economy is faring: despite all that government spending, New Zealand is still contracting on an absolute and per capita basis. And because of its structural fiscal deficit, the IMF’s latest update expects the government to continue spending well more than it collects until at least around 2030:

The IMF reported that the Ardern (and in the final year, Chris Hipkins) government rapidly increased spending on “wage bill, transfers, and social benefits”, when what’s needed was tax reform to “promote investment, and productivity growth”, along with public spending on “R&D, new infrastructure, and maintenance of the existing public capital stock”.

While it’s still early days, it doesn’t appear that the new Coalition government has any plans to credibly fix those issues, with the government unwilling to forgo election promises such as tax cuts. They seem to be more preoccupied in playing politics; for example, Finance Minister Nicola Willis recently claimed the government would “not be borrowing for tax relief” but that the government would still be adding to its debt. That’s clearly contradictory, as pointed out by economist Shamubeel Eaqub:

“It’s the same pool of money. You only have to borrow when your expenditure outstrips your revenue. The reason you borrow money is because you haven’t got enough money to fund your expenses and the net effect is what matters.”

One of the reasons the government has to borrow so much is because of another Arden/Hipkins decision to rapidly expand the public sector’s share of the workforce. In just six years, the number of public sector employees grew by 32.5%, against overall population growth of just 9.2%.

Rolling it back

The new government is starting to roll some of that back, mandating spending cuts of 6.5-7.5% across the public service, although at least one analysis concluded that “won’t even wind back the last six months of [public service] expansion”. A recent essay by political commentator Haimona Gray found that many of these are “jobs without a purpose”:

“Paying people to show up to a, likely lavish, office and just sit there doing nothing benefits no one. If that sounds like a ludicrous scenario, a right wing fantasy that would never actually happen, you’re clearly not a current or former public servant.

And there’s plenty of fat that could be cut:

“The reality is that the public service has grown massively in the past six years. Even with the coalition government’s proposed budget cuts, and the job losses that will stem from them, the size of the public sector will still be larger than it was prior to the Ardern government.

With that in mind, and when factoring in that the country is doing worse than it was according to most metrics, who benefits from a large, but futile public service? Already one fifth of all employed New Zealanders are public servants!”

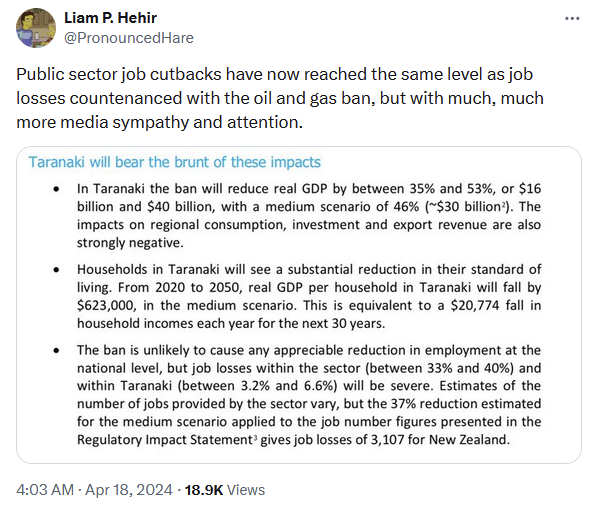

There’s always a fine balance to be struck between having a well-staffed, capable public service on the one hand, and an excessive reliance on consultants on the other. New Zealand certainly appears to have shifted too far in the public service direction, and the job cuts announced to date aren’t even that significant in the context of policy-related job losses elsewhere:

The oil and gas exploration ban was one of the Ardern government’s early policy decisions in 2018, and on top of the job losses it may have increased New Zealand’s carbon emissions by forcing it to burn more imported coal rather than domestically produced natural gas. The types of jobs lost by banning oil and gas are also generally more productive than, say, the 60 people still “working” on the now-defunct Three Waters reform plan, or the 70 people at the recently created Ministry for Ethnic Communities. If New Zealand wants to increase its productivity, it needs labour and capital to be allocated more efficiently.

How likely is that to happen? Once again, the new Coalition government talks a big game, claiming to be keen on “rigorous fiscal discipline”, but so far it hasn’t done much other than tinker at the margin to cut just enough spending to justify its promised tax cuts. Structural reform, as usual, looks as though it will have to wait. Fiscal discipline, too. But when you have a structural fiscal deficit and a shrinking economy, tax cuts today just mean spending cuts will happen in the future, or taxes will increase. As Kiwi economist Eric Crampton put it:

“The only real tax cut, when government is in substantial deficit, is a spending cut.”

Now, before moving on, I just want to point out that not everything Ardern did was economically destructive. New Zealand has actually performed much better than Australia in terms of fixing its housing mess, for example by allowing the ‘Auckland model’ to be rolled out across the country:

“A bipartisan group of national legislators upzoned areas around transit stations and job centres. Several councils fully embraced the opportunity to densify their neighbourhoods.

…

What the Kiwi experience demonstrates is how rapidly the supply side of a broken housing market can be fixed with the right political leadership. When our government upzoned Auckland, new housing starts tripled in half a decade. As Minister Bishop enacts his suite of reforms, that progress will only accelerate. The emerging academic consensus is that these changes will dramatically improve affordability in coming years.”

We may not want to replicate much else from the Ardern/Hipkins playbook (even in the housing space, KiwiBuild was a complete disaster), but a comprehensive housing reform agenda mirrored on the successes in Auckland would be highly desirable.

“At least we’re still ahead of Australia”

The Kiwis are, understandably, upset about their lot. A new survey by IPSOS found that they are growing increasingly angry at the “establishment”, with most agreeing that the system is “broken”.

According to Paul Spoonley, the former director of centre of research excellence He Whenua Taurikura, the pandemic improved social cohesion but it was only temporary:

“That unravelled, quite spectacularly, in 2021 and 2022. If we jump to the 2023 report, what we found is those high levels of social cohesion and I would suggest trust, particularly trust in government, had literally evaporated over the previous two years. The key indicator of that was the protests that were occurring around New Zealand, most notably in Wellington.”

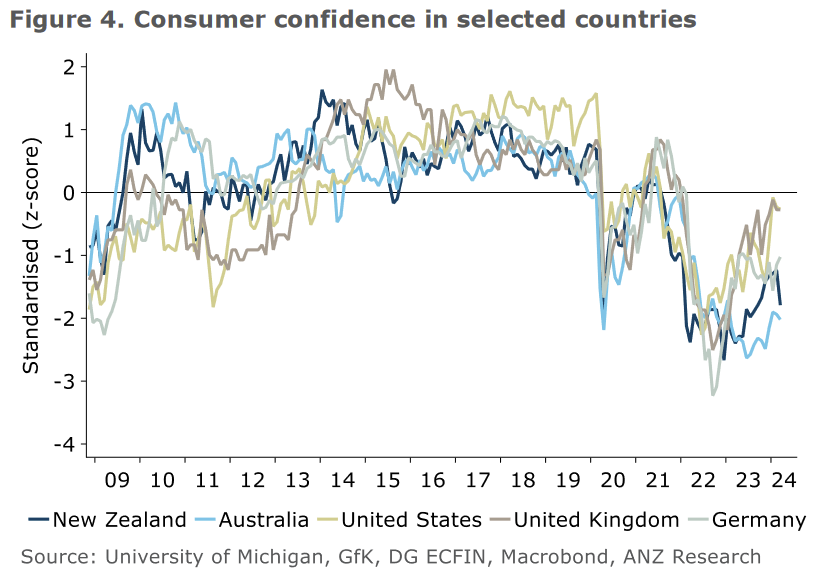

Understandably, consumer confidence remains close to record-lows. A recent ANZ-Roy Morgan report found that Kiwis’ perceptions about the 12-month economic outlook “dropped a sharp 14 points to -34%” after news broke that it had dipped into another recession, while the 5-year-ahead measure “dropped 10 points to -5%”.

But, wrote the authors, “at least we’re still ahead of Australia”, offering the following chart showing consumer confidence in Australia sitting below New Zealand, the US, UK and Germany:

If our policymakers get complacent, we could very well end up like the Kiwis with falling productivity, lower real wages and anaemic growth; consumers clearly think we’re already there!

Alas, there doesn’t appear to be another mining investment boom on the horizon, and already the signs are that the Albanese government really doesn’t understand the fundamentals of productivity. While it’s doing a lot in the name of competition and productivity, former Productivity Commission chair Gary Banks warned that “the sense of deja vu is palpable”:

“Seeking to obtain benefits to society through subsidies for particular firms or industries, including in the form of tax concessions, has proven a fool’s errand, particularly where the competitive fundamentals are lacking.

It would seem from what information is available about this initiative [A Future Made in Australia] that Australia is in danger of repeating the wrong history.

While the prime minister and treasurer have portrayed it as a new form of competition policy distinct from the ‘old protectionism’, the differences lie mainly in the instruments used and industries targeted. Import displacement is at the heart of both.”

To improve productivity and growth, we – and the Kiwis – urgently need tax reform to incentivise saving and investment; spending reform to address long-term fiscal pressures; and structural reform, especially to free up housing supply. Instead, we have a Treasurer who looks set to under-cook the economic forecasts in his upcoming Budget “to justify inflation-boosting spending” in the form of handouts.

As I wrote earlier this week, “politics will trump economics in 2024-25, and that means handouts and quick fixes will be prioritised over reform and fiscal restraint”. That will keep interest rates higher for longer, and as it did in New Zealand, a higher share of spending on transfers and social benefits in the name of ‘cost of living relief’, combined with our newfound love for unproductive industrial policy, will act as a drag on future growth.

While it’s still early days for the new Kiwi government, if they manage to get their house in order then they may soon be able to say “at least we’re still ahead of Australia” in a few more places than on the rugby field.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!