The limits to building out the suburbs

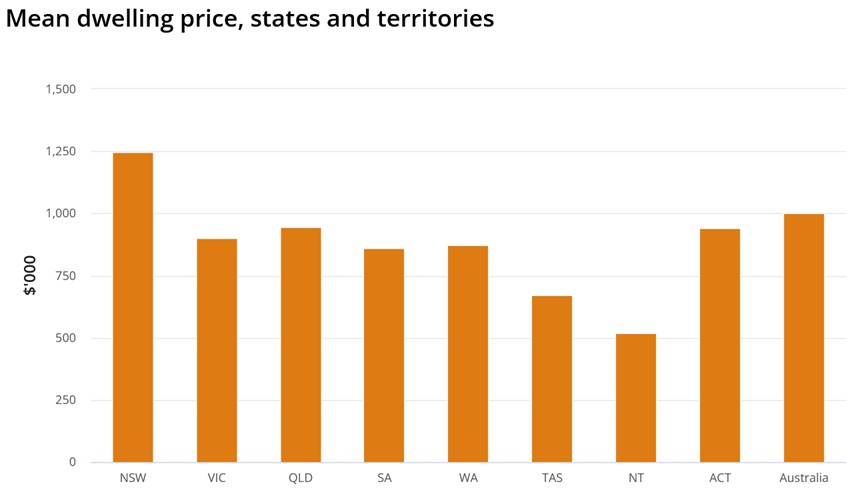

Depending on your perspective, there was some grim news yesterday: the average house price in Australia hit $1 million for the first time, although really only if you live in Sydney (averages can be misleading!):

If your goal is improving housing affordability, then that’s a problem.

The good news is the Albanese government says it’s serious about getting housing affordability back on track. It also appears to understand that the constraints to supply are almost entirely artificial. Here’s Housing Minister Claire O’Neill:

“Planning laws at the state level are being used much too much to protect existing residents, and not enough to address the fact that we’ve got millions of people who are in housing distress. We need more housing of all kinds, and medium-density housing in the middle-ring suburbs is obviously going to be a really important part of the mix.

There is a lot of work that we’re all going to need to do in the next three years, and I’d include the Commonwealth in that. None of this is an attack on the states. We’ve all been a part of this problem, and we all need to be a part of the solution.”

That’s all well and good. But talk is cheap, and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers have all but ruled out anything drastic:

“Anthony Albanese is hosing down expectations his government is about to embark on a bold new agenda just because it has a commanding majority, saying it must first deliver on what it has already promised so as not to sabotage voter goodwill.

In his first major speech since Labor’s election victory last month, the prime minister will tell the National Press Club on Tuesday that his government’s immediate focus is the delivery of its current agenda.

…

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has already nominated lifting flatlining productivity as the No. 1 challenge for the government, but says it will need more than just this term in power.Chalmers has ruled out accepting every proposal that will arise from a crisis review into productivity that he commissioned before the election, in anticipation there may be recommendations such as the need for a more flexible industrial relations system.”

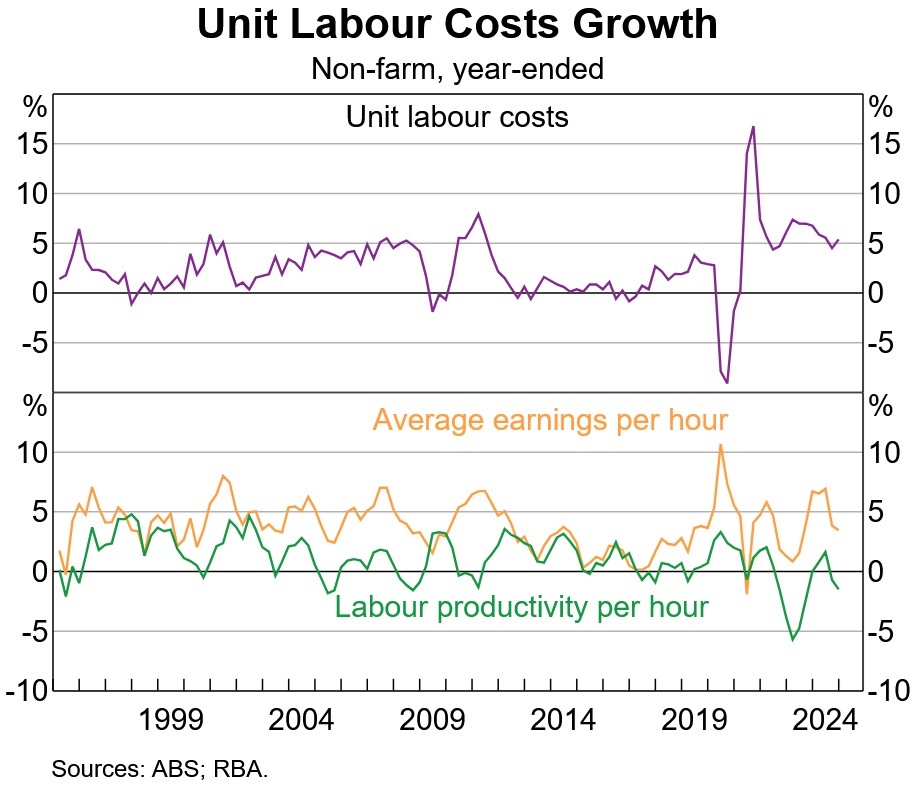

Albo also ruled out any changes to industrial relations (IR), which is a problem when unit labour costs in Australia are growing annually at a rate of more than 5%—an indicator that wages are rising faster than productivity, perhaps in part due to the Albanese government’s IR changes.

It’s also not clear how the Albanese government plans to bring state and local governments into line. During its first term, state governments effectively ignored the incentives offered in the Housing Accord to undertake meaningful zoning reform. And the signs aren’t promising that it will be any different a second time around—for example, Queensland’s deputy Premier Jarrod Bleijie intends to pour more demand on the housing supply fire:

As for local governments, well they’re never going to support more housing because the incentives are all wrong; it’s a democracy where the only people with votes are those who bought their houses through good fortune (e.g. timing of birth, inheritance), with outsiders given no voice.

This is high-stakes stuff and if the Albanese government doesn’t get its act together, the local obstructionist problem will probably only get worse. That’s because according to a new working paper by Harvard’s Ed Glaeser and Wharton’s Joseph Gyourko, which I think also applies to Australia (we certainly share similar zoning and construction productivity issues), even greenfield housing has become increasingly difficult to build in many cities.

Why? Because growth in housing demand doesn’t just raise prices but also induces a reduction in supply, creating a doom loop where places that build a lot of low-density housing in the suburbs (like Miami) gradually start to block it—until they eventually resemble ‘unaffordable’ cities like Los Angeles.

That’s a problem for Australia, because building ‘out’ rather than ‘up’ is how many cities have historically ‘solved’ their housing affordability issues. According to Glaeser and Gyourko, that model faces diminishing returns because:

- a place becomes desirable, raising demand;

- wealthy people start to move in;

- those people join the council, or attend meetings;

- they block development, reducing supply; and

- the initial demand shock has now triggered a negative supply shock.

Glaeser and Gyourko put the cause of the doom loop down to incentives:

“To us, this suggests that American housing markets increasingly follow the model put forth by Mancur Olson (1982). In his view, insiders increasingly use regulations to protect their own rents and keep outsiders out.”

They don’t offer up any solutions to the problem, but a possible escape valve is to move the decision making apparatus up a few levels of government where “insiders” will have a tougher time at capturing the regulatory apparatus. Hence why it’s so important that the Albanese government actually acts on meaningful housing reform this time around instead of just blaming the states, throwing demand stimulus at it, then dumping it in the ’too hard’ basket for another three years.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!