The Mar-a-Lago Accord

My apologies for yet another Trump tariff post, but it really is what the entire world is talking about right now. Given the size of the US economy and military along with the power the President wields with executive orders, a single comment from Trump can move markets in material ways. And for all the uncertainty caused by last weekend’s tariff dispute, the chief one remains:

What is Trump’s end-game?

Yes, Trump backed down for 30 days after Mexico and Canada struck token “deals” with the US. Both agreements were pure theatrics, with Mexico doing exactly what it did in 2019 – supposedly sending 10,000 troops to the border, a nice round number that will do nothing to stop fentanyl – while Canada simply rehashed what it had already announced in December.

As for the 10% tariffs on China, the country was effectively closed for the Chinese New Year holiday period over the weekend and the deadline slipped by. China promptly retaliated.

I have no doubt that Trump will be back for more soon enough. The tariff play-book from his first term went something like this:

- Tweet a threat, people freak out.

- Governments and politicians look for ways to appease him in the least costly way possible.

- A “deal” is struck, Trump declares victory, tariffs are avoided or watered down with exemptions.

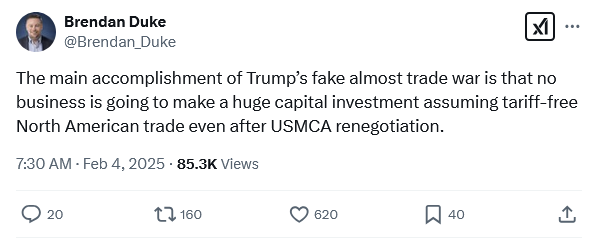

The whole process is costly, and will be costly this time as well:

But I think there’s a deeper lesson in all this chaos: that we all need to learn to take Trump at his word. Essentially, he’s a mercantilist through-and-through, who thinks tariffs are both a good thing for America and as a negotiating tool. Just because he has backed down for now doesn’t mean he won’t continue to try to actually implement tariffs.

Trump is deeply concerned with not just the overall balance of trade, but bilateral trade balances between countries. It’s a fundamentally incoherentview that economists have known to be “absurd” since Adam Smith, but at the end of the day he’s still the guy wielding the hammer.

Trump’s incomplete understanding of trade means that tariffs will be a feature of US policy for at least the next four years, regardless of how effective they turn out to be at achieving their stated goals.

But this time might be different in the sense that Trump and his advisors have had a lot more time to think about strategy and longer-term goals than they did during his first term. The newly appointed chair of Trump’s influential Council of Economic Advisers, Stephen Miran, literally wrote A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System four months ago. And it’s in there that I think we might find some answers as to what Trump is going to do, when he might do it, and most importantly, what the consequences might be.

Ripping up the global trading system

Despite cautioning that these are “my own views, not those of anyone on President Trump’s team”, the Guide reads as if it were written to be a 41-page manual “to reform the global trading system” for a future President Trump. It argues that:

- the US has suffered from a “persistent dollar overvaluation” because of its role as a reserve asset;

- that has enabled the US government to “borrow more without pushing yields higher”, creating a persistent trade deficit;

- manufacturing and tradeable sectors have suffered the most;

- the dollar as reserve asset means the US “can exert some level of control trade and financial transactions”; and

- tariffs are a good source of revenue and when combined with “a shift away from strong dollar policy” can improve “burden sharing for reserve asset provision”.

Put it all together, and:

“This connection helps explain why President Trump views other nations as taking advantage of America in both defence and trade simultaneously: the defence umbrella and our trade deficits are linked, through the currency.”

Miran is clearly a smart guy and he gets a lot right about trade policy (the same can’t be said for his new boss!). For example, he acknowledges that tariffs will cause the US dollar to appreciate, making exports more expensive, thus thwarting the goal of reducing the trade balance.

But both his diagnosis and solutions have several logical contradictions and blind spots; throughout the whole Guide it’s almost as if “he wants the dollar to be both weak and strong”.

He also puts far too much weight on foreign government US dollar reserve accumulation (Triffin’s dilemma) as the driver of dollar demand, when there are several equal or greater forces (e.g. private capital flows).

As for his solutions, they tend to involve assuming away the difficulties of implementation, administration, enforcement, and possible unintended consequences, taking it as a given that a US administration can walk a “narrow” path (where have I heard that before?) and financially engineer its way out of said pitfalls with “currency adjustments”, “forward guidance”, and graduated tariffs linked to incentives:

“[T]o help minimise uncertainty and any adverse consequences of tariffs, the Administration can use credible forward guidance, similar to what is used by the Federal Reserve across a range of policies, to guide expectations. The US Government might announce a list of demands from Chinese policy—say, opening particular markets to American companies, an end to or reparations for intellectual property theft, purchases of agricultural commodities, currency appreciation, or more. The US can proceed to gradually implement tariffs if China does not meet these demands. It might announce a schedule, for instance, a 2% monthly increase in tariffs on China, in perpetuity, until the demands are met.”

For allies, Miran argues that they could be grouped into “buckets” bearing different tariff rates, “and the government can lay out what actions a trade partner would need to undertake to move between the buckets”:

“Such a system can embody the view that national security and trade are joined at the hip. Trade terms can be a means of procuring better security outcomes and burden sharing. In [Treasury Secretary] Bessent’s words, ‘more clearly segmenting the international economy into zones based on common security and economic systems would help … highlight the persistence of imbalances and introduce more friction points to deal with them’. Countries that want to be inside the defence umbrella must also be inside the fair trade umbrella.”

Lawyers and lobbyists would salivate at just the thought of such as system!

But it gets even more problematic the further you read, because even when Miran offers a solution to a problem he correctly articulates, such as the Lerner symmetry theorem, it ends up being too clever by half.

For example, to prevent tariffs from reducing exports by just as much as imports (because a stronger dollar makes US products just as expensive as tariffed goods), thereby leaving the trade deficit unchanged, Miran proposed “an aggressive deregulatory agenda… [to] alleviate any drag on exports” from currency appreciation.

That should help initially, although simultaneously begs the question of why it’s not happening independently of the trade dispute if this administration is so keen to support trade-exposed manufacturing. And because it’s not, why would the political obstacles suddenly disappear during a trade war?

In addition, trade theory predicts that a more competitive export sector will increase production in export-oriented sectors, which over time will also offset the reduction in imports, leaving the trade deficit unchanged – one of the main objectives of Miran’s policy.

But perhaps the most naive argument in the entire Guide was when Miran argued that tariffs are “welfare-enhancing, up to a point”, but only if other countries don’t retaliate, which “can nullify the welfare benefits of tariffs for the US”.

That’s all true, but the mistake came when Miran simply assumed that concern away because in “a game of chicken”, the US is so large it can simply outlast other countries. The problem with that, as the authors of the work Miran cited to support his case pointed out, is trade wars are not games of chicken at all:

“Provided that the US is committed to high tariffs, they believe that foreigners will choose to maintain their own tariffs low for fear of entering a costly trade war against the US. The game of chicken, however, is the wrong metaphor to think about trade wars.

…

Trade wars are best viewed as a prisoner’s dilemma. Instead of staying silent, prisoners are always tempted to testify against their partner in crime in exchange for a more lenient sentence. By doing so, however, they all end up in prison for longer. Similarly, because each country has some market power to exploit, they have incentives to raise trade barriers, regardless of what the other countries do. The problem is that, when they all do so, none of them succeed in making their imports cheaper and they all end up being poorer.”

The events of earlier this week – namely Canada’s immediate, forceful threat of retaliation and China’s actual retaliation – should put to rest the idea that tariffs are a game of chicken. But this is shaping up to be a rather dogmatic administration, so they may still hold that view.

Trump probably won’t go all the way

Miran provided something of a timeline for a hypothetical Trump administration to enact his plan. Basically, it involves bullying major trading partners with “punitive tariffs”, so that they “become more receptive to some manner of currency accord in exchange for a reduction of tariffs”.

That’s where the title of this post comes into play:

“As currency accords are typically named after resorts where they are negotiated, like Bretton Woods and Plaza, with some poetic license I’ll describe the potential agreement in the Trump Administration as others have done as the prospective ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’.”

But Miran isn’t sure that Trump will go through with it. Unlike tariffs, with which Trump “is familiar… and they successfully raised revenue the first time around on China”, “currency adjustments” would raise zero revenue, which is a concern for Trump as he wants to maintain “low tax rates on Americans… [while] raising taxes on foreigners”.

Meddling with the currency would also “be a new foray for him and several of his trusted advisors have in the past warned of potentially risky side effects”.

Yes, such as global financial turmoil from a bond sell-off, private capital outflows, or a stubbornly independent Fed refusing to offset the higher price level that will come from tariffs and a devaluation of the currency (Miran did suggest waiting for “turnover” at the Fed, perhaps hinting at a major re-politicisation of monetary policy after Powell’s term is up in May 2026).

Hopefully Trump listens to the aforementioned advisors again, which would mean on the policy front it’s all tariffs, the result of which would be for “the [US] dollar… to strengthen before it reverses, if it does so”.

Notice the “if”. Without a currency accord, Miran suggests that an alternative that might appeal more to Trump would be for the US to strike deals involving “the removal of tariffs in exchange for significant industrial investment in the United States by our trading partners, China chief among them”.

That sounds more like the Trump I know and would be better for the world, to the extent that China and others cooperate (dubious), than Miran’s proposed ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’.

Finally, on the all-important timing Miran suggested that because Trump has expressed “concern for the health of financial markets… policy will proceed in a gradual way that attempts to minimise any unwanted market consequences of efforts to improve burden sharing for provision of reserve assets and the defence umbrella”.

The problem with such ‘forward guidance’ is that if you credibly communicate what you plan to do in the future, markets will price it in today, bringing forward some of the “unwanted market consequences” Miran is trying to avoid by ‘going slow’.

All up, if Trump does even half of what Miran has proposed in his Guide then we could be in for some tumultuous times. The good news is that barring a serious political miscalculation, Australia is relatively well-placed given our bilateral trade deficit with the US and that we’re home to a lot of the ‘critical’ commodities that are of interest to Trump. But even then, a more protectionist, closed-off world can never be good for a small, open economy like Australia.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!