The tragedy of Albanese

Lately I’ve been so occupied with the constant Trumpian Uncertainty wreaking havoc on global markets that I’ve barely given any attention to Australia’s federal election, which—can you believe—is now only a little over two weeks away.

So, I’m going to play a bit of catch-up with a couple of Deep Dives into each of the two candidates for Prime Minister: first Labor’s Anthony Albanese (Albo), followed by the Coalition’s Peter Dutton (likely after the Easter long weekend).

It’s obviously not a fair comparison—I’ve got three years of evidence on how Albo has governed versus nothing but speculation about, and promises from, Dutton—but I’m going to give it a shot nevertheless. Time permitting, I might even write something about the Greens and Teals—especially if they firm up as potential king makers in a minority government.

It could have been so much better

Where do I begin? Probably by stating that Albo’s government started with such promise. The chaos of the pandemic and the Morrison years had created fertile ground for a moderate, left-of-centre government to establish itself as a long-term steward of Australia’s economy—something like modern Hawke and Keating, who governed for a combined 13 years.

It was all set up so perfectly for them—Albo’s Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, even wrote his PhD on Keating! Australia had been fumbling from one election to the next for two decades with no real direction, let alone anyone willing to even discuss the reforms that we so desperately need. The global pandemic response had lined the federal coffers with paper gold, so they wouldn’t have even had to ask Australians to tolerate too much temporary pain for long-term gain.

But alas, that’s not how it played out. What we’ve witnessed instead has been a misguided blend of high-taxing, high-spending politics and ideological experiments that have left the Australian economy weaker, less competitive, and burdened with structural inefficiencies.

The early fumble

The first major mistake Albanese made was to proceed with the failed Voice referendum amidst a cost of living crisis. At a cost of around half a billion dollars, it did nothing but further divide the country at a time when we were only just getting over the socially divisive pandemic response. ‘No’ voters were labelled as racist—bringing back memories of Hillary Clinton’s infamous “deplorables” comment—and their concerns were too often met with responses like “kindness costs nothing” from Albo, rather than concrete answers.

But Albanese’s gaffes didn’t end there. Rather than being socially progressive, his government has consistently flirted with authoritarianism and anti-free speech. For example, he doubled-down on the Coalition’s shakedown of Big Tech via the link tax; banned social media for kids using pseudo-psychology based on bad data; pursued a toxic misinformation bill to the bitter end; and banned vapes, which will surely go down as one of the worst public health policy decisions in modern history—Australia now boasts a thriving black market, with “wide-ranging social, economic and health impacts”.

As for ending the rorts of the Morrison government, Albo himself was dragged through the mud because of his relationship with former Qantas CEO Alan Joyce, forcing him to defend free overseas business class flight upgrades, his government’s decision to block Qatar Airways from launching 28 new flights per week, and his then-19 year-old son’s Chairman’s Lounge membership.

Proving he has no feel for optics, he then went and purchased a $4.3 million beach mansion right when the housing affordability crisis was climaxing.

The neopopulist delusion

If Albo was just getting the social stuff wrong, Australians might have been forgiving. But he hasn’t been all that great on economics, either, and I think a lot that can be traced back to his choice of Treasurer—Jim Chalmers.

In January 2023, with inflation running at 7.8% annually, Chalmers published an infamous 6,000-word manifesto that he later claimed was the “opposite of… the neoliberalism of the pre‑crises period”:

“I genuinely believe in some of those people who I greatly admire from the ’80s and ’90s… the vast achievements of those incredible performing governments under Bob and Paul. But we have to recognise that the world moves on, and we need to move with it. Because if we get stuck in the past, this country will be poorer.”

The great irony in that statement is plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

By abandoning neoliberalism, Chalmers believes he’s being original—hence ‘moving on’. But his “values-based capitalism” is in fact nothing but neopopulism, which is itself built on the failed, pre-neoliberal ideas of the ’60s and ’70s. It draws from the ideas of Chalmers’ mentor Marianna Mazzucato (whose academic work has failed to replicate), and is effectively an argument for a return to 1960s-style “mission-oriented” industrial policy via a “co-investment model”:

“We will employ this co-investment model in more areas of the economy, with programs already under way in the industry, housing and electricity sectors.”

Chalmers’ vision was eventually lumped into a Future Made in Australia, about which I have written plenty (and not in a good way!). The long and the short of it is industrial policy isn’t likely to bring you growth. It’s a rebranding of the old models of inefficient, government-led resource allocation, and is more likely to lower growth and real wages through its negative impact on productivity.

Now, there might be valid strategic reasons for doing industrial policy, or you might want to achieve some other non-economic goal—say, having everyone drive an electric vehicle by pushing down their relative price through subsidies. Those arguments are weaker in an economically small, natural resource-heavy, geographically isolated country like Australia. But you can still make them, provided you acknowledge that it will involve taking on more debt, lowering productivity, and reducing incomes.

My main frustration is that Chalmers doesn’t address these trade-offs; he promises growth, “good jobs”, along with security and economic “resilience”. He also fails to acknowledge any of the downsides—state capture by vested interests that entrench inefficiencies, the waste from ‘picking losers’, and that even if their intentions were pure, politicians and their bureaucrats probably don’t have the requisite knowledge to pull it off.

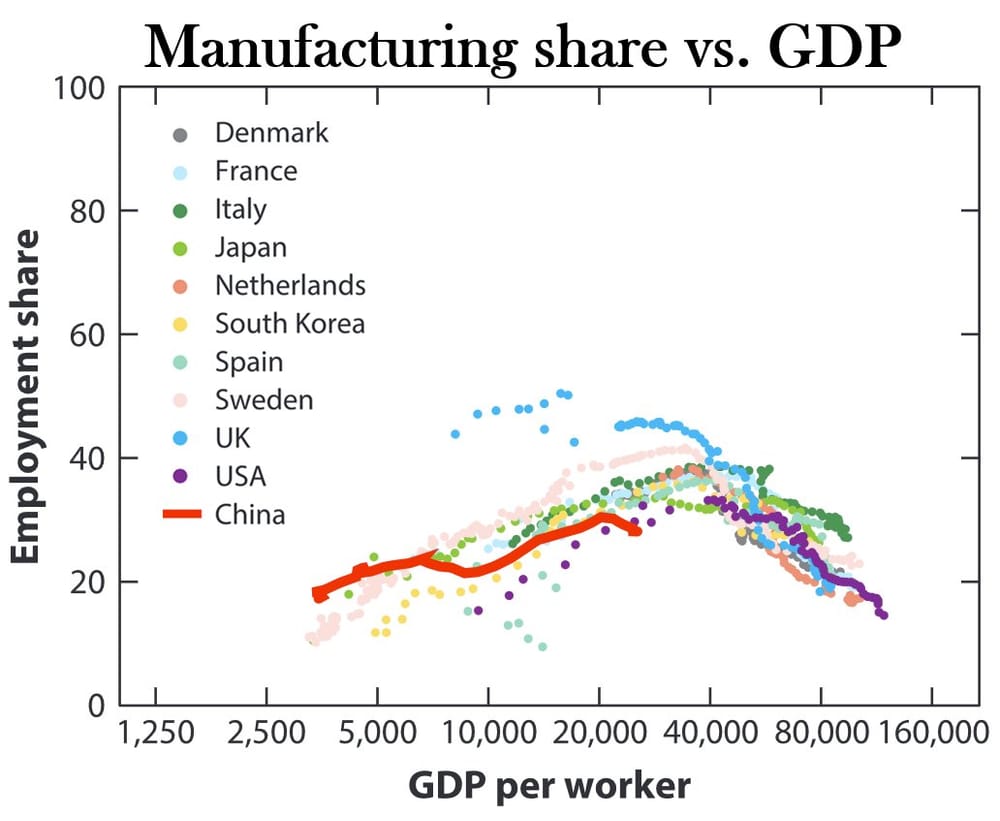

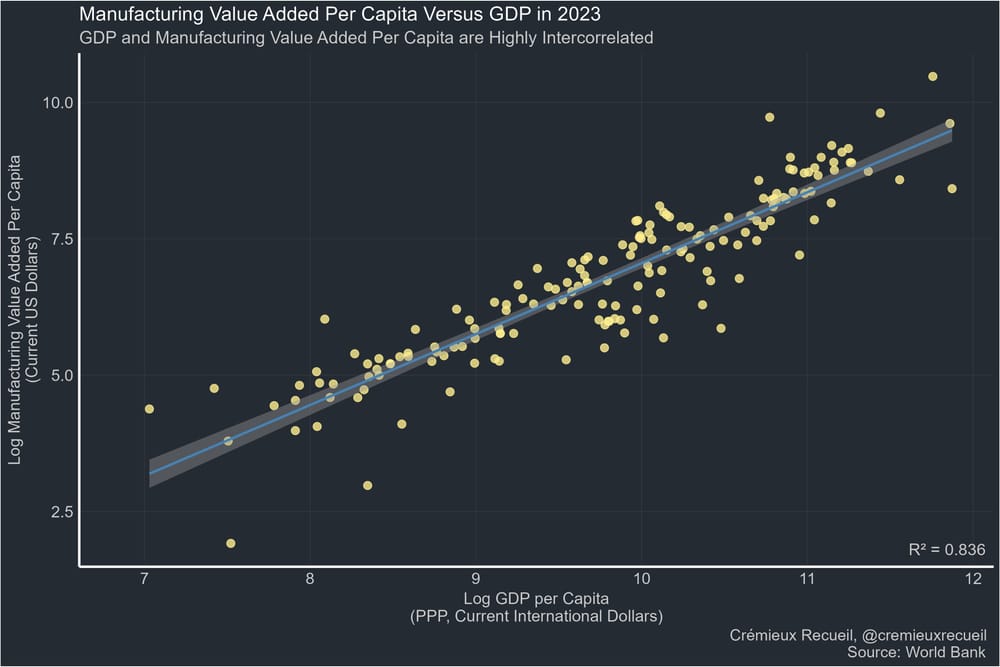

The Albanese government is obsessed with returning manufacturing jobs to Australia, even though its share of employment has been in decline ever since WWII, following the pattern of agriculture before it. The cause isn’t globalisation or some deep-seated conspiracy of capital against labour, but the natural consequence of modern technology, productivity, and the rise in demand for services relative to goods. It’s a pattern that can be observed in all economies as they get wealthier— even China—and trying to fight it with broad-based industrial policy like a Future Made in Australia will only do so by making us poorer.

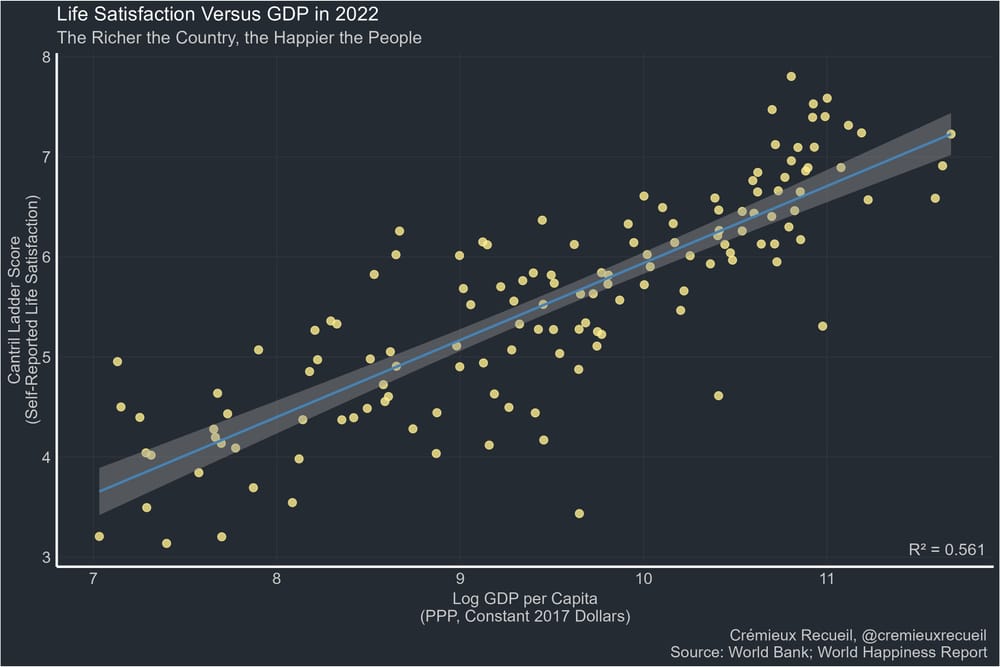

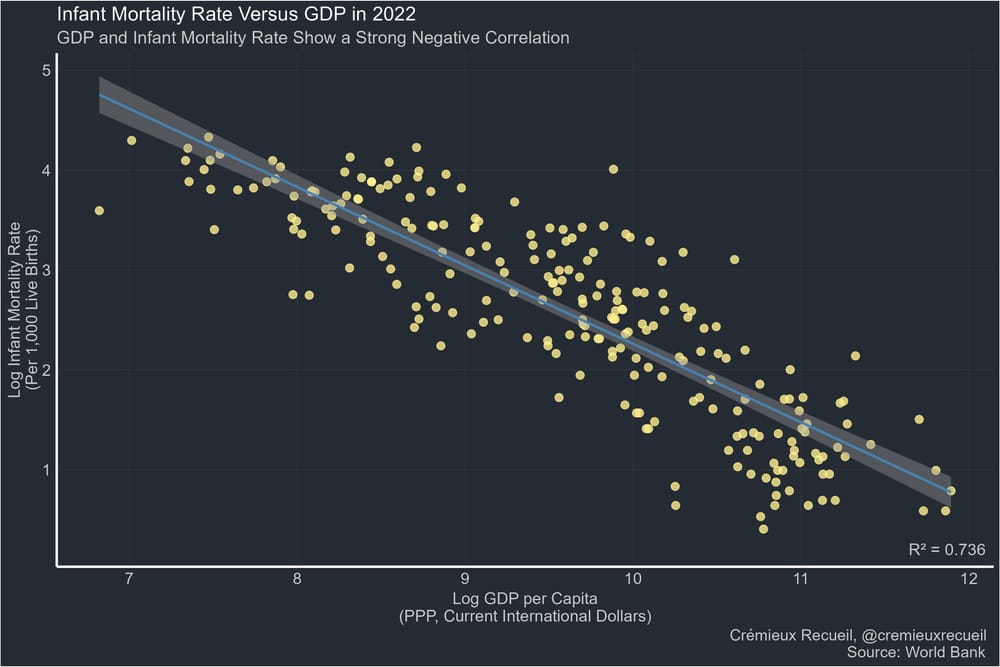

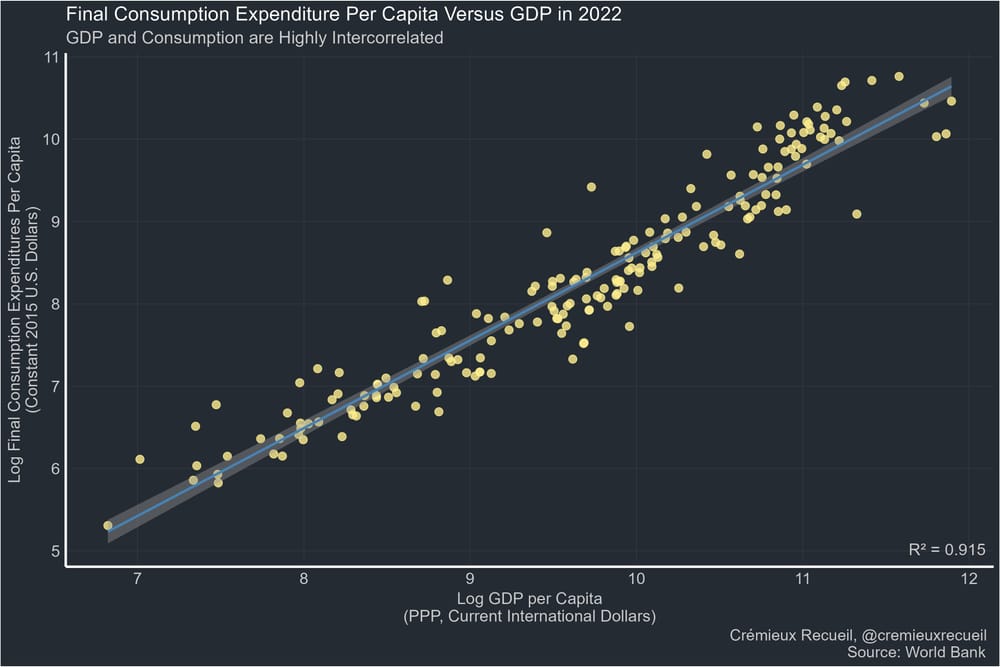

Finally, while I agree with Chalmers that the neoliberal obsession with GDP is overblown and “values” are important, the fact is almost everything good in society correlates pretty darn closely with GDP.

What Australia desperately needed—and still needs—is supply-side reforms to boost productivity. So-called Dutch Disease is a real concern, but the most effective way for a federal government to deal with that is by running budget surpluses and squirreling away the proceeds of any revenue windfalls to provide a buffer for when the day comes that the golden goose stops laying eggs.

Instead, Albo has delivered endless subsidies and winner-picking industrial policy; policies that historically deliver inefficiency and waste, are eerily similar to his social policies—that is, substituting the judgement of people making deals with their own private property for the ill-informed and ill-directed judgement of government officials.

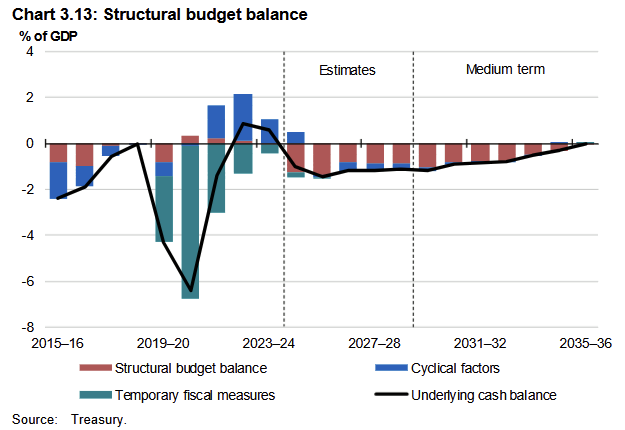

It means that after three years, Australia now has more debt both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP than when Albo came to power.

Blowing the fiscal luck

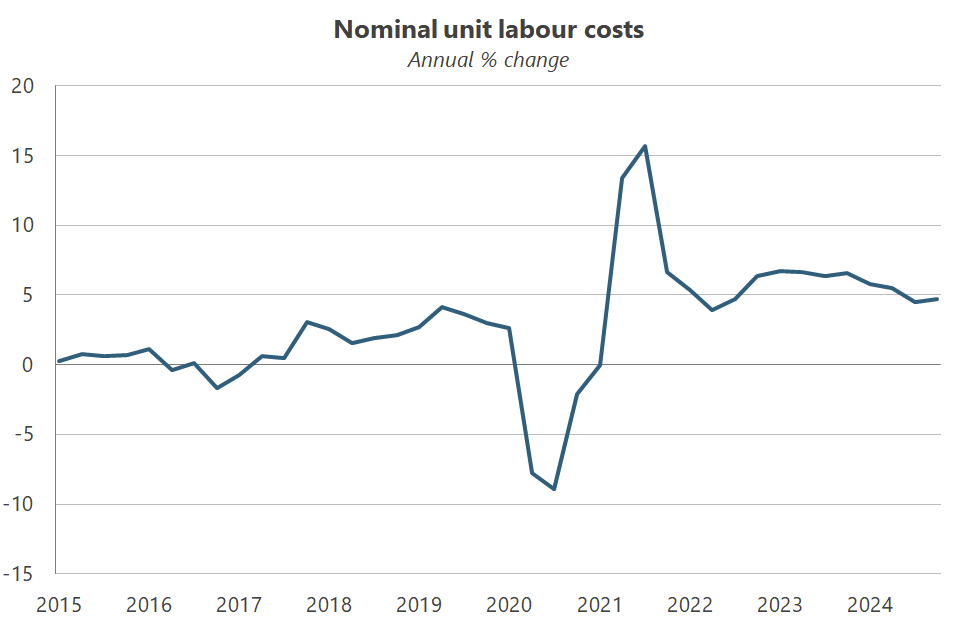

The Albanese government, without a doubt, mishandled the inflationary cost of living crisis. Given the historically-low unemployment throughout its term, government spending has effectively crowded out the private sector, driving up the prices of materials and equipment, wages for certain workers (unit labour costs are still growing at 5% annually), and interest rates for businesses looking to invest.

Instead of reigning in fiscal spending—the true cause of the inflation—it embarked on a spending spree for the ages.

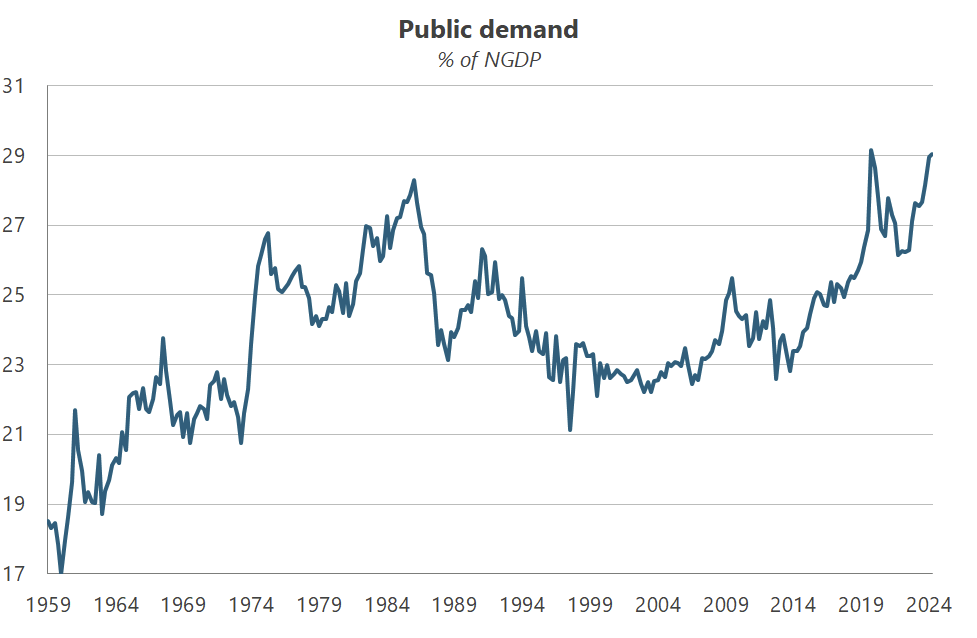

After three years of Albo and Chalmers, the federal budget remains in structural deficit, with government spending now at a record high 29% of GDP (excluding the pandemic). Taxation and other government revenue are hovering near record highs as a share of GDP.

Unfortunately, this is what you get when you borrow heavily from the Elizabeth Warren/Joe Biden play book. Tokenistic measures like freezing beer excise taxes to shave 5¢ off the price of a pint well after inflation had driven up prices (unlike income tax, beer is automatically indexed twice a year) will do little to alleviate household pain, but does reveal a government more focused on optics than substance.

$20 billion worth of student debt forgiveness—done entirely off-budget (so much for transparency!)—is regressive and inequitable, and won’t do anything about the cost of living.

Then there were the bulk billing changes “that put three dollars in the pockets of doctors for every dollar they put in the pocket of patients”. Great for the medical lobby, but would fail any reasonable cost benefit analysis if health outcomes rather than optics were the actual goal.

What about the emissions standards regulations that energy minister Chris Bowen tried to gaslight us into thinking would save people money? Or the broken $275 lower power price promise that he was still repeating well into 2024, despite soaring inflation making such a nominal price target ridiculous?

Just the hubris of this government to think it can, or should, control nominal prices is astounding. Its stubborn refusal to adjust, despite inflation providing the perfect cover under which to pivot, was remarkable.

And who could forget housing.

I don’t actually blame the Albanese government for its failure to build a single home under its flagship scheme, let alone meaningfully address housing affordability. Its mistake was in claiming that it could spend its way out of the problem—a plan that implicitly assumed that there’s some kind of market failure for why the private sector isn’t building enough to satiate demand.

But it misdiagnosed the problem; there’s no market failure, only a long-running government failure. It just doesn’t matter how much you spend if you don’t address the mostly state- and local-level constraints that suffocate construction productivity and prevent supply from being added by public and private developers alike.

But what I do blame it for is taking out $10 billion of debt in our collective names and investing it in risky equities via the Housing Australia Future Fund, which is now at risk of needing a top-up “as falling share prices and mandated withdrawals consume its capital base”.

I also blame it for politicising the regular old Future Fund, which it should have terminated instead. And, of course, its latest policy that effectively subsidises young Australians to make poor financial decisions by leveraging themselves to the gills to buy their first home, all while stimulating demand—and so driving up prices.

Finally, what has Albo done for Australia’s economic competitiveness? The recent events over in the US have demonstrated how important trade is for our present and future prosperity. But while Albo and Chalmers have reaffirmed their belief in international free trade, their actions on domestic free trade—e.g. the strengthening of labour laws that protect jobs, not workers, thereby reducing productivity—have done the opposite.

The same is true for Albo’s energy policies, which exemplify the government’s inability to balance ambition with practicality. Its naive, back-of-the-napkin commitment to accelerate the transition to 82% renewables by 2030 has been marred by poor execution and unintended consequences.

Instead of reducing energy costs for households and businesses, these policies have undermined Australia’s competitiveness—at least until Albo temporarily buried them with $7 billion-and-counting worth of electricity subsidies, which could have been better used to upgrade the aging grid (a major driver of energy costs), or invested in gas or nuclear generation to complement renewables.

Such self-inflicted domestic impediments to trade can be just as damaging as international ones. As former Productivity Commission chair Gary Banks wrote:

“On the one hand, we have been busily eliminating our comparative advantage in energy, while on the other we are reviving our traditional disadvantage with respect to labour. This has helped suppress investment and productivity growth, and taken a toll on real incomes.”

Will three more years of Albo do anything to ease those self-inflicted impediments to growth, or will it be more of the same?

Another three years?

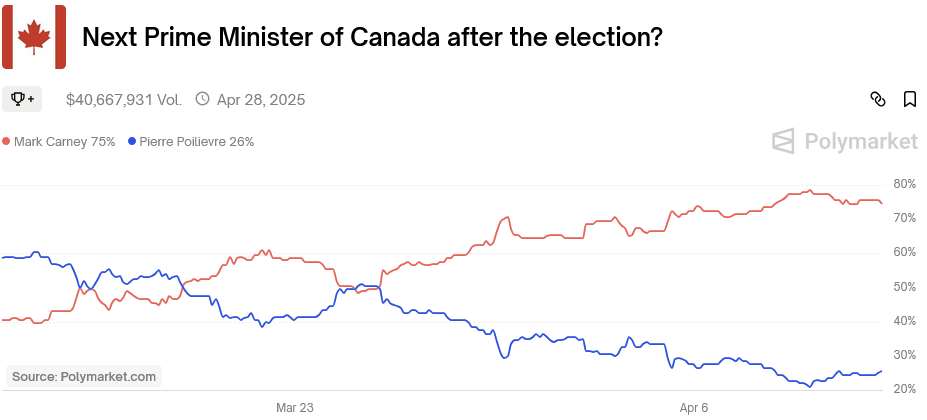

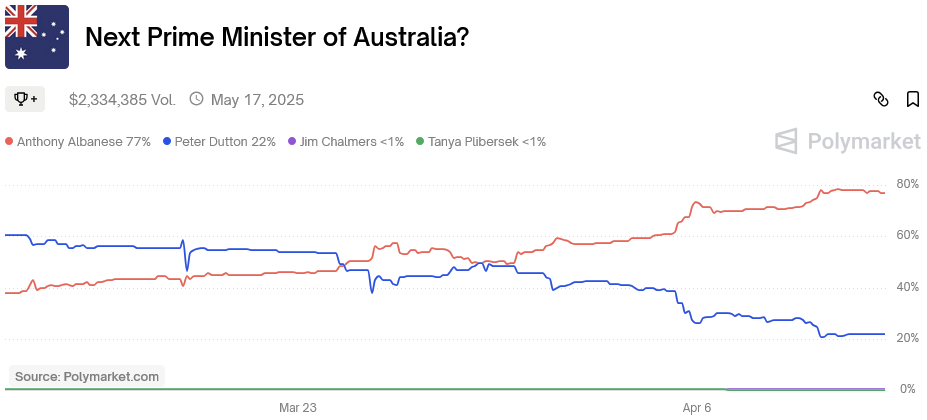

Albo is likely to get another term—but not because he has won over the hearts and minds of Australians. No, prediction markets have turned sharply against oppositions in both Australia and Canada, as the ongoing effect of Trumpian Uncertainty has (rightly) soured voters against their respective conservative oppositions.

And Albo’s reign hasn’t been all bad. For example, his government’s pharmacy reforms and recent banning of non-compete clauses were great, though its National Competition Policy revival has stalled—but at least it tried.

But those were all relatively small fish, and Albo and Chalmers have given no indication that they even understand the problems with their agenda—they’re not quite in 2019 Chris Bowen “if you don’t like our policies, don’t vote for us” territory, but they’re not far off—and many of their worst policies, such as taxing unrealised gains on superannuation and the anti-free speech disinformation bill, are simply waiting for the election so that they can have another go at bribing swinging a few independents to support them.

As for their new proposals, there’s nothing all that new, really— cash splashes on health and fee-free TAFE, subsidies for first home buyers that will simply drive up prices, childcare and solar battery handouts for the well-off, and who could forget the comical $5-a-week income tax cut. Perhaps what’s most revealing is what isn’t being discussed, such as any ideas for how to boost Australia’s ailing productivity, how to stop the NDIS blowing out even further, fixing the structural fiscal deficit, sustainably tackling energy costs, or untangling the Gordian Knot that is Australia’s mess of a tax system.

On the latter point, the just-announced $1,000 standard tax deduction is a great first step that will reduce compliance costs, which can be significant because of the opportunity cost of time (or paying an accountant)—but I worry that once the election’s over, that’s exactly where it will stay for the next three years. And like all tax cuts in Australia this one isn’t indexed to inflation, meaning the benefits will fade over time.

So, three more years of Albo and Chalmers—assuming Albo doesn’t simply retire to his beach mansion in a year or two—will likely see them chasing the same ideological, post-neoliberal unicorns they did during their first term, while the real issues compound for yet another political cycle.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!