The trilemma of age limits, Housing constraints matter, Prices work, and What grows productivity.

Here’s some of what I’ve been reading from outside Australia recently, along with a few short thoughts on each.

The trilemma of social media age limits

The Albanese government’s social media age limits— a bad idea based on junk science—will be in place by the end of 2025.

New Zealand’s conservative government is now looking to do the same, and like Australia’s, the plan is for it to be enforced by platforms.

But according to Kiwi economist Eric Crampton, both are doomed to fail to achieve their stated goals because of the “trilemma [that] applies for any system that puts the obligation on platforms”:

- The system is easily circumvented by those under the legal age.

- The system is onerous for those over the legal age.

- The system means the effective end of social media pseudonymity/privacy.

In a follow-up post, Crampton envisions an end-game scenario:

“The more the regime is successful in keeping kids off of the regulated platforms (at cost to adult users), the more that kids will be pushed onto platforms that have not yet been designated. Those platforms will then be designated. Discord. WhatsApp. Various videogames that have chatrooms or that enable chat. Compliance burdens continue to rise, except on platforms outside the reach of New Zealand regulators, like 4Chan.

The stable equilibrium at the end of that? Substantial hassles for users over the age limit and/or the end of pseudonymity, some kids deterred from using platforms, others out on forums that are far worse than where they are now.”

My stable equilibrium is probably earlier in the trilemma—point 1—and we’ll just end up with a bunch of “Yes I’m over 16” age boxes to sit along side the “Yes I accept cookies” boxes. Like these that are already on every brewery website:

At least I hope so, as that would also be the least costly equilibrium for the country. 🤞

Yes, supply still matters

A few months ago, a controversial new paper found that constraints on housing supply didn’t matter all that much for prices or the quantity of housing—that the laws of supply and demand don’t apply to housing.

However, according to follow-up work by UBC’s Michael Wiebe, it turns out they made a couple of basic—but critical—mistakes, including:

- Using total income growth as the shift in demand, where total income = average income * population. But this is not a shift in demand. Population growth is correlated with housing supply constraints: it’s harder to move into a city that blocks new housing.

- Depending on an implicit assumption: that a city’s supply elasticity (ψᵢ) is uncorrelated with total income growth (Ŷᵢ). But this assumption is not true. More constrained cities will have lower population growth.

Wiebe concludes that “the empirical results are uninformative about the role the housing supply constraints”.

If I were to state the main issue with the paper differently, the authors basically ignored that making housing scarcer through supply restrictions is itself a deterrent to population growth! Or as Alex Armlovich put it, the paper essentially found that “Conditional on adding 1 worker, we find that YIMBY & NIMBY cities alike add 1 worker.”

So, pure nonsense: economic theory, supported by the balance of empirical work on housing that shows supply constraints do affect prices and quantity, still holds.

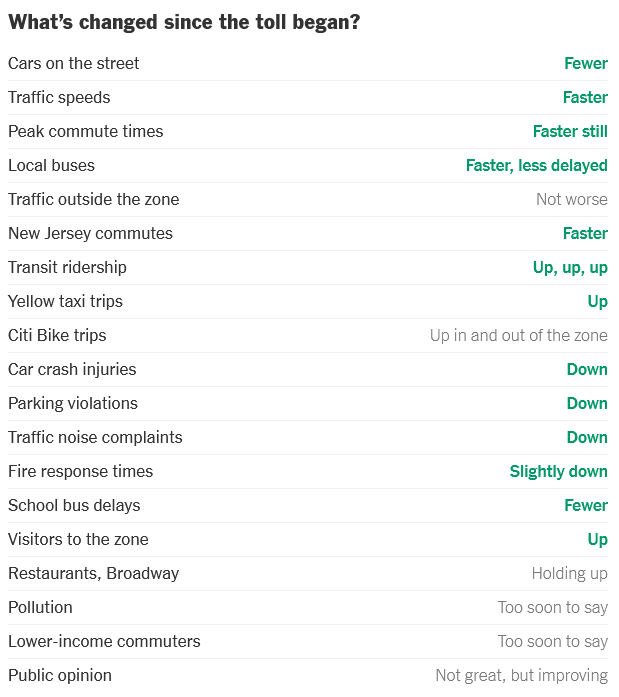

Yes, prices do work

I’ve written before about how congestion on Australia’s roads—a major externality— is only an externality because of the political choice not to price roads appropriately. The recent experience from New York’s implementation of congestion pricing (flawed as it may be) is yet another arrow in the quiver of evidence in support of that position:

If our state governments properly priced their roads, they could reduce the amount they subsidise public transport (~$11 per trip in WA), cut back on how much they spend on costly road infrastructure, and curtail pollution and traffic externalities. They’d also be able to use any additional revenue raised to eliminate highly inefficient taxes, like stamp duty.

And yes, the same is true for carbon, as a new Review of Economic Studies paper found:

“Using administrative data, we estimate that, on average, the European Union Emissions Trading System—the world’s first and largest market-based climate policy—induced regulated manufacturing firms to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 14–16% with no detectable contractions in economic activity. We find no evidence of outsourcing to unregulated firms or markets; instead, firms made targeted investments, reducing the emissions intensity of production… We show that the absence of any negative economic effects can be rationalised in a model where pricing the externality induces firms to make fixed-cost investments in energy-saving capital that reduce marginal variable costs”

If you don’t want as much of something, whether it’s traffic congestion, carbon emissions, or even immigrants, then don’t cap it, ban it, or subsidise uneconomic competitors (e.g. a Future Made in Australia)—just raise the price!

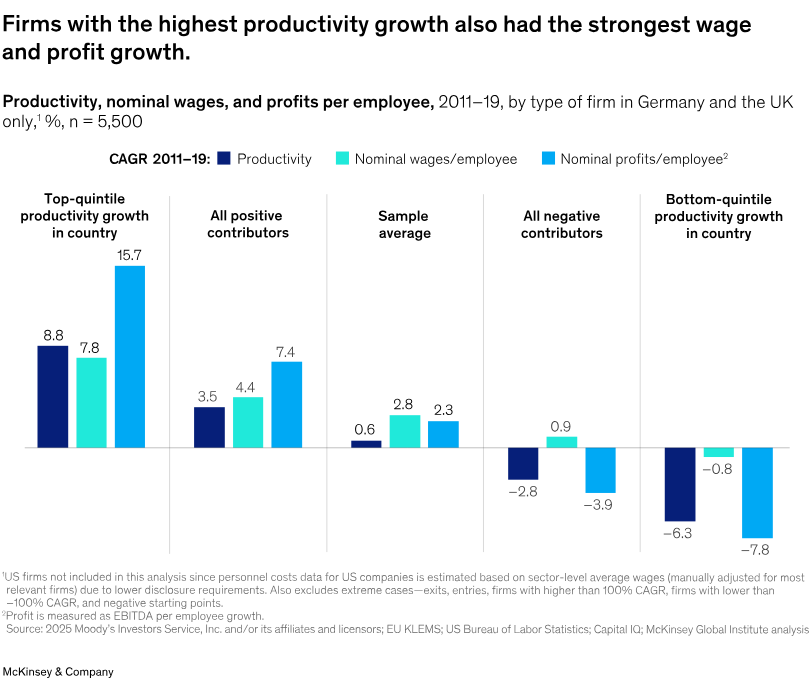

What grows productivity

Growing productivity is how countries sustainably increase incomes and living standards, yet Australia has had virtually none of it for the past decade. A new McKinsey Global Institute report recently took a look at what drives productivity in a few different countries (alas, not Australia), finding that it’s usually just a few large, highly productive firms that drive the overall trend:

“Fewer than 100 firms in our sample of 8,300—a group that we have dubbed Standouts—accounted for about two-thirds of the positive productivity gains in each of the three country samples we analysed. Standouts are defined as firms that added at least one basis point to their national sample’s productivity growth.

To give a sense of how important a single firm can be, just another dozen or so of the largest Standouts could have doubled productivity growth in their entire country.”

Higher productivity firms lead to stronger increases in wages and profits:

The US has outperformed other countries, and McKinsey reckons one reason might be because it “has highly dynamic factor markets, allowing for quick entry and exit as well as fast scale-up and restructuring”.

Food for thought, especially given the Albanese government’s various moves to make the labour market more more rigid, mostly by protecting jobs rather than workers. Similarly, its plan to prevent mergers that might increase market concentration (even though concentration is a poor measure of market power) risks unintentionally preventing leading firms from growing, harming productivity growth (and incomes!) in Australia.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!