The Trump Slump, Full marks for Albo, Energy prices are telling us something, and Gittins it wrong on inflation (again)

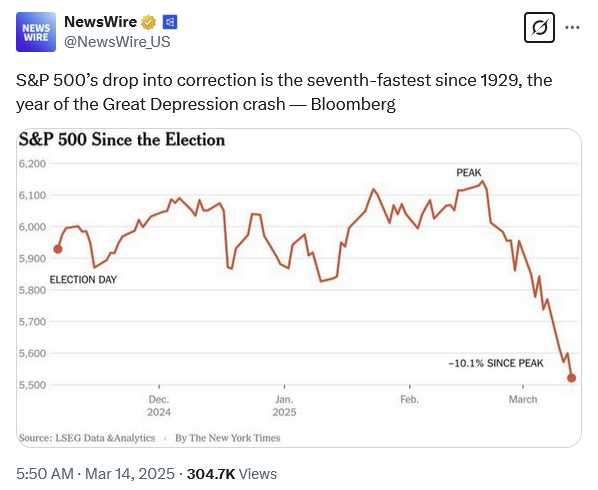

The Trump Bump has officially become the Trump Slump, with the current US administration’s incessant focus on tariffs contributing to one of their greatest tailspins of all time:

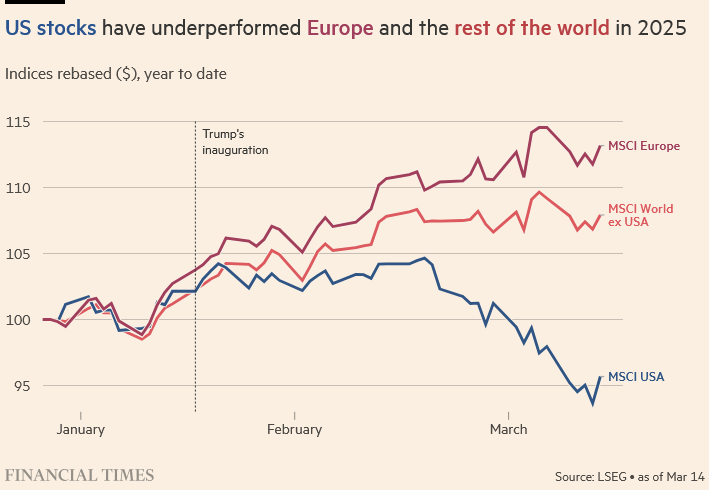

The crash has been uniquely American:

Markets are forward-looking—they reflect investor consensus of what’s likely to happen to returns in the future. If they’re recoiling like this, it means they expect the short-term pain Trump’s inflicting to not generate the long-term gains he’s promising.

Now, that doesn’t necessarily mean there will be a US recession; as the old joke goes, the stock market has forecast 9 out of the last 5 of those. But if Trump persists with his tariff nonsense—neither he nor the true believers in the Trump 2.0 administration have given any indication that he’ll stop—growth expectations and share prices will continue to adjust accordingly.

Albo made the correct decision

I was happy to read that Anthony Albanese elected to respond to Trump’s blanket 25% steel and aluminium tariffs by not retaliating, given that tariffs primarily punish your own citizens, rather than those of the targeted country:

“Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said Wednesday that U.S. tariffs on Australian steel and aluminum were unjustified, but his government would not retaliate with its own tariffs.

…

‘Tariffs and escalating trade tensions are a form of economic self-harm and a recipe for slower growth and higher inflation. They are paid by the consumers. This is why Australia will not be imposing reciprocal tariffs on the United States,’ Albanese added.”

Spot on. Given that Trump appears to like tariffs for tariff’s sake—there’s no 4D chess move where he’s trying to get all countries to lower their trade barriers going on here—retaliating will only make matters worse. If you need evidence of that, both Canada and the EU responded aggressively and all it got them was the threat of more tariffs:

“US President Donald Trump on Thursday threatened to slap a 200% tariff on wine, cognac and other alcohol imports from Europe, opening a new front in a global trade war that has roiled financial markets and raised recession fears.

…

Trump’s threat came in response to a European Union plan to impose tariffs on American whiskey and other products next month – which itself is a reaction to Trump’s 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium imports that took effect on Wednesday.”

Trump’s tariffs will push up prices for American consumers, while simultaneously damaging the very manufacturing industries he claims to cherish, and all because he doesn’t understand the basics of trade. Why would Australia’s politicians ‘retaliate’, causing even greater damage to their own economy?

The good news is that Australia just doesn’t trade all that much with the US, and especially not steel and aluminium, which “represent less than 0.2% of the total value of our exports”. And as we saw with the restrictions China imposed on goods like barley, coal, wine, and lobster a few years ago, Australia’s exporters are pretty good at finding new homes for their goods. Further, because Australia isn’t being singled out and other countries have retaliated, there’s a chance that Australian exporters will soon find new, more lucrative opportunities to replace the US market.

So, well done Albo. But the real test will come after 2 April, when Trump’s ‘reciprocal’ tariffs are supposed to kick in. For example, will Trump target Australian agriculture—specifically meat, which accounts for nearly 30% of Australia’s goods exports to the US (or more than $4 billion)?

No one knows (that’s part of the problem!), but the pressure from lobby groups to ‘do something’ in response will grow louder when a greater share of exporters are targeted. And it’s not like there’s a shortage of voices on both sides of politics calling for such action. For example, Queensland Senator Gerard Rennick wanted to respond to the aluminium and steel tariffs by “protecting our steel industry by imposing tariffs on foreign steel… [so that] we might start making more of these beauties”, along with a picture of a few cars made in Australia back in the 1970s.

I shouldn’t have to tell regular readers why that’s an awful idea, and it’s probably a good thing that Rennick’s Senate six-year term will expire on 30 June after he was dumped from a winnable position on the Liberal National Party’s ticket.

But closer to Albo’s ear are people like former Labor leader Bill Shorten, who—from the comfort of his new vice chancellor gig at Canberra University—said that “if they [the US] keep putting tariffs on our goods, we need to reciprocate dollar for dollar, tariff for tariff”:

“I do worry about the next sector and the next sector, it is steel and aluminium today, is it agriculture and farmer tomorrow? I think at some point we will have to send a message to Trump … if you do something to us, we’ll do it back to you.”

I’ll just say that for all the chaos that was Scott Morrison’s government, it’s probably a good thing he defeated Bill Shorten in 2019, because raising taxes on imports and effectively self-sabotaging your economy in response to someone self-sabotaging their own is perhaps one of the stupidest things you could do.

When a country levels tariffs on you, you don’t need to respond in kind. Let Trump retreat into isolationism and undermine his country’s growth prospects.

Instead, the best response Australia could make would be to look at strengthening its ties with the rest of the world. Most politicians are like weather vanes; they move with public opinion, rather than setting it. And there could be something of an Overton window open right now, where global public opinion has turned against Trump and everything he stands for—including protectionism—and so politicians might be willing to discuss trade liberalisation with Australia.

Basically, rather than ‘fighting’ Trump’s acts of idiocy by also shooting ourselves in the foot, we should be sending delegates throughout Asia, and to the UK, EU, and Canada. Australia is a small, open economy that will benefit from any reduction of trade barriers elsewhere. Go and spread the word that we’re still open for business!

Energy prices are telling us something

Power bills on the Eastern seaboard are set to rise by up to 9% later this year:

“In a draft decision landing on the cusp of a federal election, the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) has on Thursday recommended an increase to the so-called default market offer (DMO) in multiple states.

The benchmark price will climb by up to 8.9 per cent for some households in New South Wales, 5.8 per cent in south-east Queensland, and 5.1 per cent in South Australia.”

According to the AER, the increase was due to:

“[F]actors such as high demand, coal generator and network outages, and low solar and wind output that drove high price events across DMO regions. These high price events have also affected the price of wholesale electricity contracts for 2025–26.”

I’ve written before that power prices are determined not by the average unit, but by the marginal unit—i.e., the cost of producing the last unit of electricity needed to meet demand, rather than the average cost of all the electricity produced.

If you add more intermittent renewables into the system but don’t have the capacity to store it all, you drive down marginal costs during the day but actually raise marginal costs for the coal or gas plant that now has to sit idle for longer. Those power plants are forced to recoup their total costs over a shorter period of time, which can cause power prices to spike during peak periods once the sun has set.

That doesn’t necessarily mean average power prices will be higher with a heavy-renewables grid; the near-zero marginal cost renewable power could more than offset the higher peak period costs of running fossil fuel generators. But unless you have enough storage (e.g. batteries, pumped hydro) or intermittent capacity (e.g. gas) in the system, renewables do degrade the total system reliability and raise price volatility.

When that’s combined with high “inflation and interest rates”, along with aging coal power plants and associated infrastructure that is starting to fail—because what owner in their right mind would invest new capital into an asset that has been told it has a limited shelf life—the end result can be higher electricity prices.

This is essentially what happens when a government pulls-forward a transition to renewables before the whole system can handle it (in WA, the government is forcibly shutting down solar panels because it can’t store all the energy, raising network costs). The solution is to make the peak-period marginal generation cheaper (e.g. lower gas prices), or have renewables determine the price more of the time—e.g. through lots more investment in renewables combined with battery storage or pumped hydro.

Unfortunately, that means there are no quick fixes. These sort of unintended consequences are precisely why I detest targets like Labor’s ‘82% share of renewables by 2030’, a goal that was arbitrarily magicked into existence “from a speech Albo gave in December 2021 that was picked up by ‘many journalists and lobby groups’, and was then adopted by the government itself”.

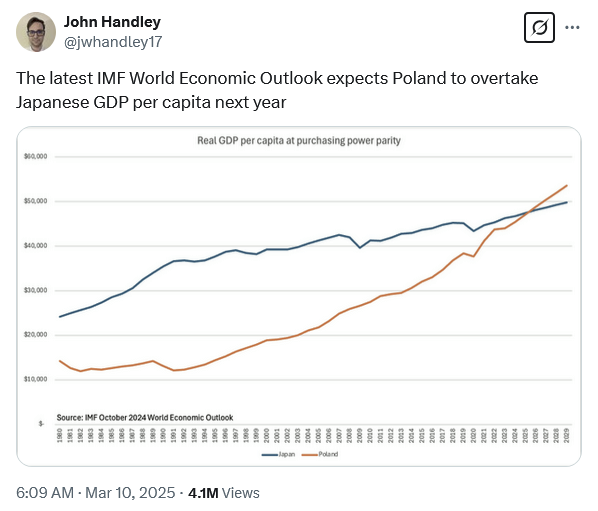

Fun fact

As the sun sets on Japan, it’s only just rising in Poland:

Gittins it wrong on inflation, again

After spending 600 words dunking on the economic profession’s “maths and econometric models”, Australia’s economics columnist-in-chief, Ross Gittins, decided to grace us with his own model of inflation. It’s too long to quote in full, so here’s an AI summary:

“This model argues that inflation surged not just due to supply shocks from the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but also because businesses took advantage of the moment. During the pandemic, goods demand spiked while services spending collapsed, leading to shortages and higher prices. When energy prices jumped after Russia’s invasion, media coverage amplified inflation expectations, giving businesses an excuse to raise prices further.

The model suggests that for years before this, inflation was too low because businesses hesitated to raise prices unless others did the same. The supply shocks gave them the cover they needed to break that hesitation, creating a self-fulfilling inflationary cycle. Even after supply disruptions eased, many of these price hikes remained in place.”

Gittins calls this effect “signalling”, which he says is not captured by “their [economists’] equations”:

“Not only were firms signalling to customers that, due to causes entirely beyond their control, big price rises were unavoidable, they were signalling to all their mates that now would be a great time to whack up their own prices.”

Needless to say, Gittins’ model is complete junk. The mainstream models he criticises already include forward-looking expectations—a more sophisticated version of his nebulous ‘softening up’ “signalling” model. He offers zero empirical evidence showing a causal link between such signals and inflation, other than an anecdote about the ABC giving “much publicity to some wiseguy claiming the price of a cup of coffee would jump to $8”, which is supposedly evidence that “[b]sinesses were using the media to soften up their customers for big price rises”.

Gittins also completely ignores the demand side. If greedy businesses all suddenly conspired to all raise prices—something they were unable to do in the years prior to the pandemic, supposedly because “[e]veryone was waiting for some inflationary event to give them some cover, but nothing turned up”—how were households able to afford to continue purchasing at these new, higher prices?

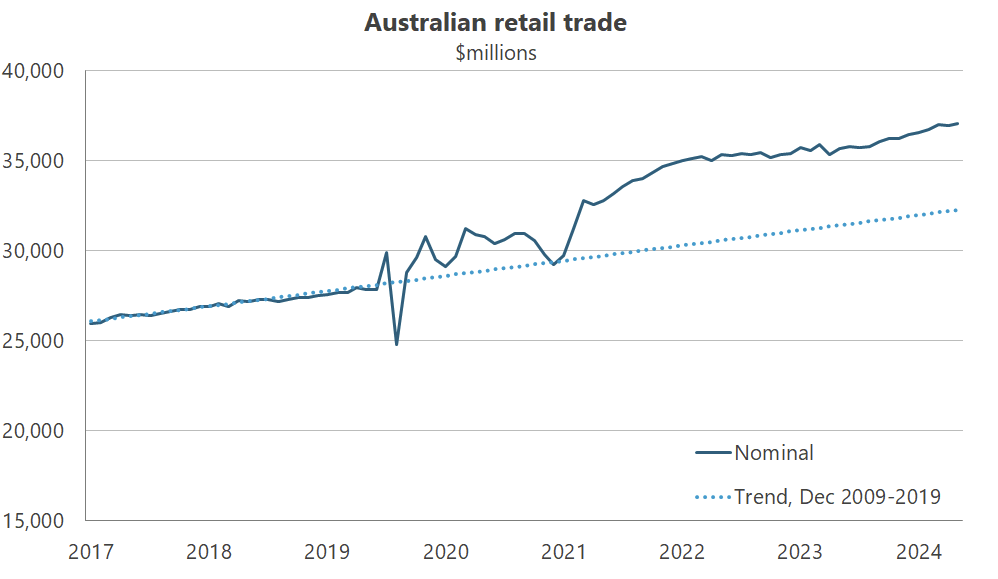

Basically, how did this happen:

I’ll add that the same thing also happened in just about every country around the world—were they all sitting around for years, “waiting” for cover to uniformly jack up their prices?

I honestly don’t know how Gittins can write this stuff down and not immediately delete it in shame.

Businesses always aim to maximise profits. If they could raise prices arbitrarily, they’d have done so earlier when inflation was low for years; they don’t need an excuse! Contra Gittins, greed played almost no role in the pandemic inflation because greed is a constant.

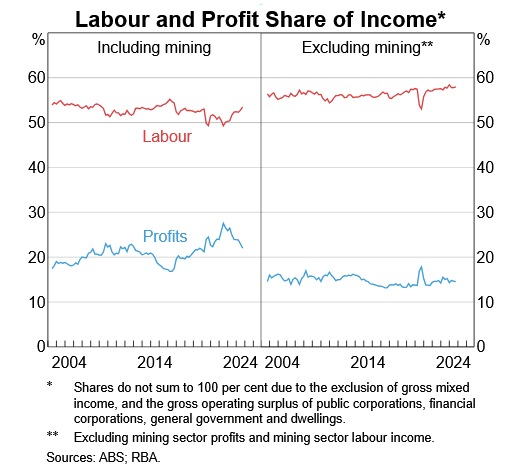

Moreover, the profit share of income—excluding mining, which is largely a price-taker—never materially increased, while the labour share has:

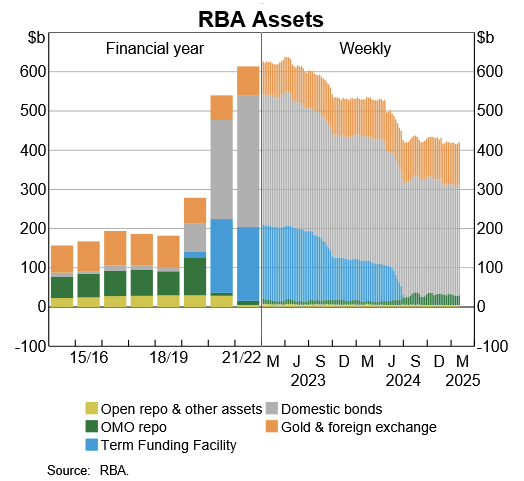

What did change was monetary and fiscal policy, which took a rapid and unprecedented turn, injecting billions of dollars into the economy that juiced demand—more dollars chasing a relatively fixed number of goods and services—leading to a decline in the overall purchasing power of money (i.e., inflation). Just look at the explosion in the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) balance sheet:

When demand exceeds supply, prices rise as markets clear. This isn’t a self-fulfilling prophecy; it’s microeconomics 101, the lessons from which Gittins appears to have forgotten.

Further reading

- Trump may be repeating the mistakes of Roosevelt that worsened the Great Depression: “Shortly after the U.S. imposed the retained profits tax in 1936, the economy slumped. The S&P Index dropped 35% from peak to trough. Business investment collapsed. A survey of Illinois manufacturers found that 83% had deferred or abandoned plans for expansion. It was called the ‘Roosevelt Recession.’ Lammot du Pont, president of the Dupont chemicals giant, complained to the National Association of Manufacturers in December 1937 that ‘industry is blanketed by a fog of uncertainty… the whole future is a gigantic question mark.’ The same holds true today. Investment strategist Gerard Minack is warning of an adverse supply shock. Given the uncertainty already unleashed by Trump’s White House, it may already be too late to turn back.”

- “Quantum-level BS and hype”: Microsoft’s quantum computing breakthrough " doesn’t actually demonstrate" that it can do what it says. That billion-dollar ’ investment’ in Queensland is looking dodgier by the day.

- Why the US has an air traffic control problem: “The federal government recently announced pay boosts for new air traffic controllers and more efficient hiring processes. But anyone over age 31 is too old to apply, limiting the hiring pool. And the vast majority of controllers are forced to leave their jobs a decade before standard retirement age.”

- One of the worst ‘investments’ in Australian history: “Up to 31 December, NBN Co had received $31.1 billion of cash investment from taxpayers while accumulating lifetime losses totalling $35.6 billion. Even including this latest $3 billion taxpayer ‘investment’, NBN Co will have lost every cent and more that the Commonwealth has provided.”

- An interesting history of how the pineapple went from being the world’s most coveted fruit to accessible to nearly everyone.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!