The truth behind Australia's fiscal recovery

This will be the first of two posts digging into a few interesting economic events that happened last week, starting with the federal budget. For as you may have heard, Treasurer Chalmers gleefully revealed that the final 2023-24 financial year results came in much better than expected:

“The federal government recorded a $15.8 billion surplus for the 2023/24 financial year, a $6.4 billion improvement on the forecast in the May budget, data released on Monday showed.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers attributed the budget turnaround to lower government spending.

‘It’s not about higher commodity prices, it’s not about more taxes – it’s about the less spending’, he said.”

Chalmers is clearly aware of the public’s perception that his government is spending too much, or he wouldn’t have gone to such pains to say that it wasn’t.

But he’s only telling half-truths. While it’s true that the total tax take was largely unchanged, the composition was very different than expected: taxes on incomes and consumption were up a lot over the past six months (~8%), while those on profits were down by about the same amount. The former is up because of inflation, for which his government is at least partly responsible, while the latter is down not because of decisions made by Chalmers, but because commodity prices have fallen.

It’s similar with spending. Chalmers’ half-truth is that the government spent less than it expected when it made the projection five months ago. But as economist Chris Richardson pointed out, that’s largely an “accident of timing” – e.g. big government projects moving slower than expected – and an accident of the economy, with a strong labour market “keeping spending lower than expected in some areas”.

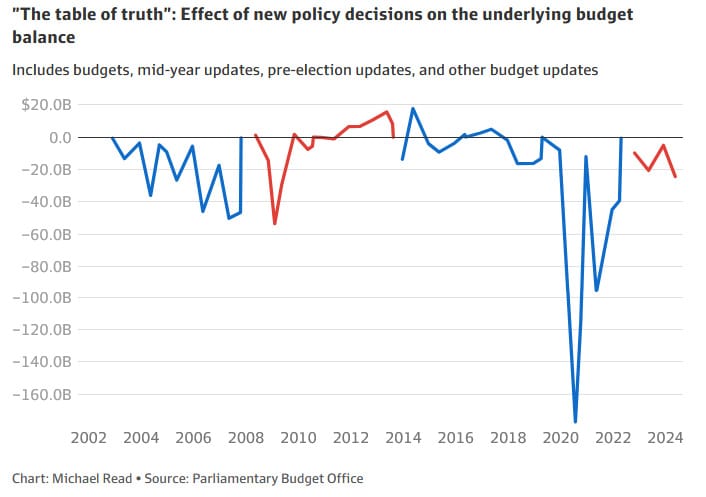

The truth is that the surplus would have been even larger if it weren’t for Chalmers and his government:

It’s good news that the fiscal situation isn’t as dire as was predicted earlier this year. But because of the decisions taken by this government, and because the factors that saved the budget are unlikely to repeat, it may be a long time before we see a surplus again.

The decade of deficits

The Australian economy has a lot of strengths, which have helped to repair the federal balance sheet. The unemployment rate is close to record-lows, which along with inflation-induced bracket creep, has seen robust income and consumption tax revenue. Key revenue-driving commodity prices such as iron ore are still well above their long-run averages, boosting the corporate tax take. Economic growth, while weak by historical standards – and deeply negative on a per capita basis – is still positive. The ASX200 is close to record highs, which would have helped pad superannuation balances and, along with record house prices, helped to create a bit of a wealth effect.

As a result, federal net debt as a share of GDP fell from 28.4% of GDP in 2020-21, to 18.4% in 2023-24, despite total government spending reaching a record 27.3% of GDP in the same year.

Therein lies the problem: because the government couldn’t even rein in spending during the good times, how likely is it that they manage to do so during ’normal’ times? God forbid if there were to be another crisis giving them an actual excuse to spend more! The fact is record government spending as a share of GDP means the tax burden has increased, even if people don’t feel it yet because it has been shuffled off into the future in the form of debt.

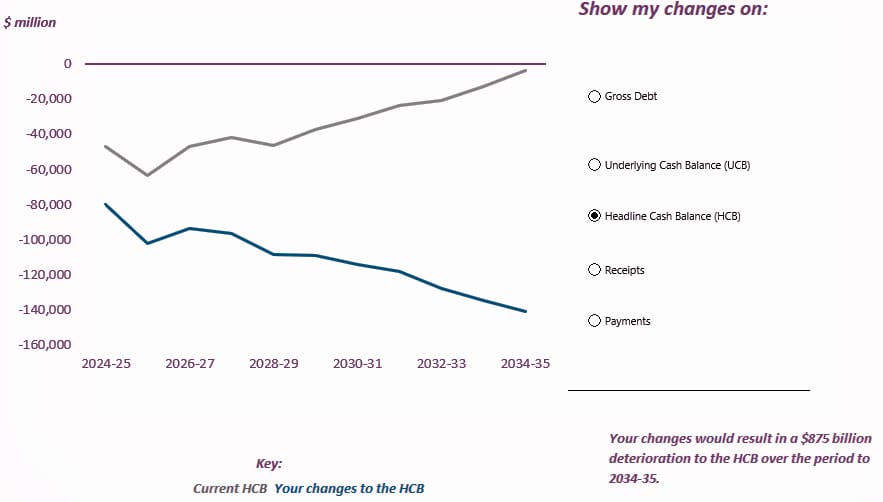

That’s why Treasury’s projections are for a big deficit in 2024-25, and then more deficits ad infinitum. And if you tweak the PBO’s build your budget tool just a little – moving Treasury’s economy assumptions to the ’lower’ scenarios – you’ll see it can quite easily get a whole lot worse:

It’s especially worrying when you consider than a lot of the measured strengths in the Australian economy may actually be signs of weakness. For example, government spending is driving demand with the side effect of bidding workers away from the private sector:

“We definitely think there’s some crowding out going on”, EY senior economist Paula Gadsby said.

Ms Gadsby said record high spending, especially in infrastructure, was pushing up costs and was adding to existing pressures through supply chain and from labour shortages.

Construction costs have rocketed 35 per cent over five years nationally."

Treasurer Chalmers likes to boast about how many jobs have been created during his tenure. But what he never mentions is that at least two thirds of them are non-market jobs (I say “at least”, because many private jobs have the government as a major client too):

More government spending while close to full employment, with more people employed by the government, will crowd out private employment and investment (the government is competing with the private sector for loanable funds, so raises interest rates). That’s basic economics, as is knowing that if the spending is not done all that efficiently, it will also lower future productivity and the government’s ability to service the debt with future taxes.

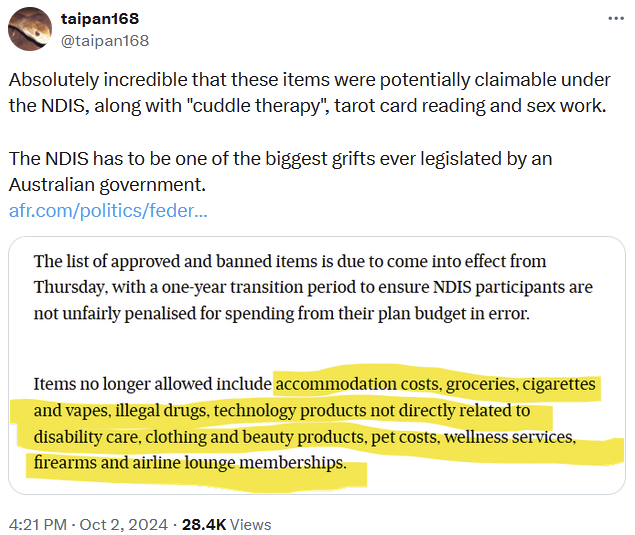

And as we know, a lot of those new jobs are in health care, largely due to the ballooning National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). That money is almost certainly not being spent efficiently, unless you consider these ‘items’ to be a productivity-enhancing use of tax dollars:

It’s good that the government is finally cracking down on the blank cheque that is the NDIS. But when the NDIS money dries up, so too will many of the jobs dependent on it, and Australia’s economic situation might start to look a whole lot worse.

That is, of course, assuming it can be cut off; interest groups have a strong incentive to dig their heels in, keen to preserve the huge benefits that are currently flowing their way, while the costs are dispersed across the rest of us who can only shake our heads in dismay (but have little incentive to actively lobby against it).

Once set in motion, that’s a powerful mismatch of incentives that can be hard to break! No wonder the Minister for the NDIS, Bill Shorten, is jumping ship.

Pro-cyclical policy is counter-productive

The second thing that happened last week was the International Monetary Fund (IMF) released a Statement from its recent official staff visit to Australia. It reported that the federal government’s recent Budget “is projected to deliver a positive fiscal impulse”, its cost-of-living support “may inject some additional stimulus into the broader economy”, and state Budgets “have proven more expansionary than expected in the near-term”.

In other words, our governments are making the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) job more difficult. the IMF warned that if the current stance of monetary policy – which it deemed to be “appropriate” – failed to get inflation down, then:

“…expenditure rationalisation at all levels of government could help lower aggregate demand and support a faster return of inflation to target. In particular, infrastructure spending could be carefully prioritised to avoid aggravating construction capacity constraints, by focusing on boosting productivity and facilitating the green transition. In addition, transfers should be made targeted wherever possible.”

While politicians are always keen to blame Ukraine and other supply-side issues for the inflation, those only play a small role: recent work by European Central Bank researchers concluded that the post-pandemic inflation in the US was caused simply by too much demand. Australia undertook a similarly-sized positive fiscal shock in 2020-21, so our inflation probably had the same causes:

“Empirical evidence suggests that at the beginning of 2020 and 2021, net tax revenue shocks were very important drivers of the inflation surge. This evidence largely corresponds to the period when the pandemic fiscal packages were adopted and suggests that these transfers had long-lasting effects on inflation and contribute to explaining the persistence of core services inflation.”

Similarly, the Peterson Institute for International Economics found that “supply chain breakdowns were not a principal cause of pandemic-era inflation”, and that if governments want to avoid inflation, they should do it “through improved demand management”.

Basically, every level of government is engaging in debt-financed spending at the same time – even if it’s for infrastructure, some of which is no doubt important – adding to demand while we’re in a demand-induced inflationary shock. It’s pro-cyclical fiscal policy en masse and is one of the more irresponsible forms of budget management out there.

The good news is the IMF recommended plenty of polices that would help, many of which I’ve covered before. For example, tax reform that “target[s] system efficiency and fairness, reducing reliance on direct taxes and high capital costs that hinder growth”, and housing policies that address “structural challenges such as restrictive planning and zoning regulations, high land costs, infrastructure deficits”.

In the longer run, the IMF is all about policies that will improve productivity and competition, which is hardly controversial. The government just has to do it.

The fact is without decisive action on these fronts, Australia risks falling behind its peers, burdened by high spending and a lack of economic flexibility. Sustainable growth requires more than just a temporary fiscal surplus – it needs reforms that address the nation’s underlying structural challenges. And while the current Labor government has had plenty of time to do just that, it seems much more comfortable delivering incoherent speeches and resorting to short-term gimmicks aimed to deceive, a worrying trend that I’ll explore further in the next post.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!