The unwanted Budget, Don't blame Alfred for inflation, Productivity not protectionism, You don't need six figures to afford rent, Dutton's dangerous idea, and Solar's Achilles' heel

Please note that I’m travelling internationally this week and will have limited access to a computer, so Aussienomics will be taking a short breather ahead of the inevitable chaos that will be the run-up to the federal election, which—if called by the end of this month—could be held as soon as 3 May.

Normal service should resume in the early/middle part of next week. Until then, please enjoy this super-sized update!

The Budget that no one wanted

Tomorrow is federal Budget night. It’s only happening because Cyclone Alfred rudely decided to interrupt Labor’s plan for an April election, triggering the mandatory Budget process that it was hoping to skip.

It won’t be pretty. Last week, Treasurer Jim Chalmers confirmed that the surpluses of recent years are gone, and that we shouldn’t expect any fireworks because they were all announced back when it was hoping to skip this charade:

“‘Most of the big initiatives under these headings have already been announced,’ [Chamlers] said of the key budget themes of health, childcare, education and infrastructure.

‘There’ll be provisions in the budget for policies we will announce in the campaign, not next week. All this means there will be fewer surprises on budget night.’

Among the policies yet to be unveiled, Chalmers promised more ‘meaningful and substantial’ cost of living assistance.”

Ah, “cost of living assistance”, more accurately described as debt-financed cash handouts for things like energy rebates that temporarily reduce measured inflation but make actual inflation—which is what’s really hurting people—even more painful.

What they also make worse are budget deficits, which Deloitte expects to gradually send net debt from 19.6% of GDP this year to 23.9% by 2027-28. But it’s an election year, so hiding the true state of the nation’s finances while buying votes with things like interest free loans and boosting pensions for asset-rich retirees will again be the name of the game.

Deloitte estimates that the amount of ‘off balance sheet’ spending—expenses in things like waiving HECS debt, the NBN top-up, and the Whyalla steelworks bailout that were classified as “investments” to obscure their budgetary impact—is likely to be around $100 billion, but you won’t hear about that in the figures the Treasurer reads out tonight. Add that to the billions of dollars in forecast revenue from measures unlikely to pass parliament, and you get this:

“One reason Australia’s longer-term fiscal health might not get the attention it deserves is because it’s too easy for politicians to paint the numbers any colour they feel. Even voters who care deeply about the country’s finances can be forgiven for not knowing what to believe. It’s no longer as simple as reading the bottom line of the budget papers.

…

The medium-term budget outlook is getting worse, not better.

Add to that the parlous nature of most state finances, in large part driven by unchecked vertical fiscal imbalance, and the structural view of the national balance sheet gets even worse.”

As economist Chris Richardson wrote last week, the country’s finances have worsened because both sides of politics have a perpetual spending problem:

“Spending was 24.4 per cent of national income in 2022-23, but it’ll be 27.2 per cent next year. That’s the fastest and largest increase in the size of the federal government since Whitlam’s expansion half a century ago.

Luckily, that lurch coincided with our luck, so we still saw surpluses. Yet luck is temporary, whereas the promises we’re making to ourselves are permanent.”

The OECD’s latest report warned that you can only play that game for so long:

“Decisive fiscal actions are needed to ensure debt sustainability, preserve room for governments to react to future shocks and generate resources to meet large impending spending pressures. Stronger efforts to contain and reallocate spending and enhance revenues, set within credible medium-term adjustment paths tailored to country-specific circumstances, are key to ensuring that debt burdens stabilise.”

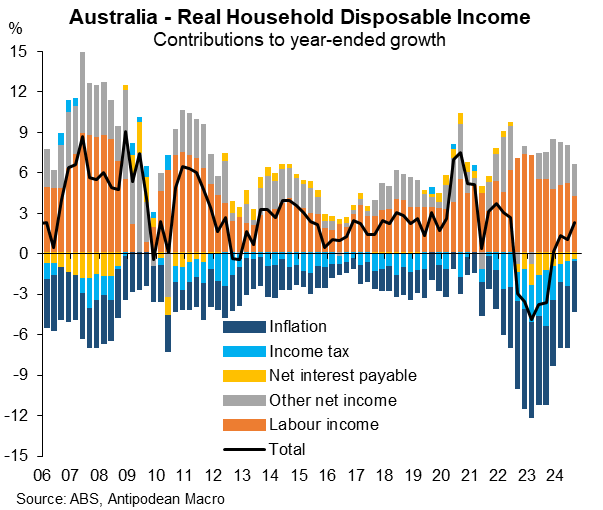

Australia has been blowing its fiscal load in the good times, with no OECD nation increasing its public debt as a share of GDP as quickly as Australia has over the past two decades:

While that was from an enviably low base, it’s the trend (difference between the green and orange bars)—and complete silence from both major political parties on the issue—that’s most concerning.

Cyclone Alfred won’t drive up inflation

Treasurer Jim Chalmers was out and about last week trying to blame poor old Alfred for inflation:

“This [cyclone] could wipe one-quarter of a percentage point off quarterly growth. It could also lead to upward pressure on inflation from building costs to damaged crops raising prices for staples like fruit and vegetables.”

The first half of that is true—Alfred caused real damage, and as Chalmers noted elsewhere, the estimated 12 million work hours lost will come at a cost.

But the second half of his statement is sloppy at best, dishonest at worst. While it’s true that inflation as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) might increase, that’s only because the CPI is sensitive to short-term shocks and weighting quirks. A cyclone in and of itself will do nothing to inflation, which is a sustained, general rise in the price level, eroding the purchasing power of money over time.

Basically, unless the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) botches its response because it fails to ’look through’ what will be a temporary blip in the CPI, then all we’ll get are relative price changes—which is not the same as inflation. And the RBA is unlikely to botch its response, unless it has somehow forgotten the " years and years" it spent “working out how to separate the underlying component from the froth and bubble on the surface”.

Chalmers either doesn’t grasp the distinction, or doesn’t care. Either way, it’s not a good look for the nation’s Treasurer.

Productivity not protectionism

The chair and deputy chair of the Productivity Commission (PC) penned a timely opinion piece last week, rightly praising the Albanese government’s response to the economic self-sabotage that’s happening across the Pacific.

As to what Australia’s government should do in response to the madness, they write:

“First and foremost, we should remain steadfast in advocating for free trade, including encouraging other countries to avoid the use of tariffs, as well as other measures.”

Yep. Exactly what I’ve been recommending. Wood and Robson continue:

“Increasing our direct barriers to trade and investment – even if we did so in retaliation – would come at a high cost to our economic growth and living standards. For example, we estimate that if Australia and other countries introduced a 10 per cent tariff in response to a general 10 per cent tariff from the US, then Australian prices would rise 0.2 per cent. Similarly, our GDP would be 0.14 per cent higher if we did not retaliate, even if other countries do.

…

For Australia, the policy lesson is clear: we should keep our hands clean and resist the temptation to retaliate with self-harming tariff increases of our own. Direct retaliation is a road to nowhere.”

It’s good to see some modelling results being produced. Australia is a small, open economy, which means for all the self-harm the US is doing to itself with tariffs, responding would be even worse for us—we’re not capable of producing even a small amount of what we want to consume and invest.

But tariffs aren’t the only way a government can respond. For example, Australia has targeted US tech companies with things like ’link taxes’ in the recent past. While there might be a case for reviewing certain aspects of the free trade agreement we have with the US now that Trump has breached it (e.g. extended copyright terms that favour US companies), Wood and Robson warn against retaliating “indirectly with additional, non-tariff measures”:

“These measures – which can include subsidies, stronger anti-dumping protections or local content rules – also tend to distort economic outcomes and raise prices for consumers and costs for producers. But they are less transparent than tariffs, which is no doubt part of their appeal.

These so called ‘behind the border measures’ have been on the rise globally and in Australia for many years.

Using these tools as a retaliatory response to the current environment risks being as much of a dead end as direct tariff increases.”

Subsidies, anti-dumping protections, and local content rules—where have I heard those before? Oh that’s right, they either form the backbone of Albo’s Future Made in Australia, or they soon will be if union influence on that wasteful make-work scheme grows any stronger.

Let’s hope that when Trump’s “Liberation Day” rolls around on 2 April that Albo and Chalmers continue to listen to their advisors rather than their party’s donors.

Fun fact

Data, data, everywhere:

No, you don’t need a six figure income to afford rent

I know I shouldn’t expect much from the ABC, but you’d think with over a billion dollars of taxpayer’s money pumped into them each year they could at least afford to hire an economist to check what they’re putting out there. Alas, clearly no economist was on hand to check this stellar piece of journalism:

“A new report by campaign group Everybody’s Home found that a single person now needed to earn at least $130,000 to comfortably afford a typical unit.

The group said the findings underscore an “alarming shift” in the housing market.

The rental crisis is no longer confined to Australians on lower incomes.”

The ABC is citing the findings of a report produced by an activist lobby group as fact. But a simple look at the report’s assumptions along with publicly available income data would have raised serious questions about its credibility. For example:

- it uses a non-standard measure of affordability by defining it as 30% of net, rather than gross, income on rent, instead of the 30-40 rule which defines stress is when as housing costs are more than 30% of gross income and income in the bottom 40% of the distribution (which would preclude anyone earning $130,000);

- only around 10% of Australians earn over $130,000, and very few of those who do rent, so this methodology implies that a huge portion—perhaps all—of the 30% of the population who currently rent would be considered “stressed”; and

- in the real world, stronger-than-average income growth for renters has likely reduced, not increased, the number of renters who are “stressed”. This is supported by HILDA data, which found housing stress peaked in 2018, reached an all-time low of 7.7% in 2021, and has only risen slightly since then.

Reports like these, by effectively lumping everyone who rents into a “stressed” bucket, pulls attention away from those who are legitimately struggling such as single-parent families who rent. They do this country a disservice, and the ABC—as the public broadcaster—should know better than to report it as fact, regardless of how many cheap clicks it generates.

How not to do competition reform

When a politician says they want “reform”, it doesn’t always mean it’s for the better. For example, Peter Dutton has recently spoken about wanting to forcibly divest the supermarkets and insurance companies.

But in doing so, he’s likely conflating concentration with competition, as one of his conservative counterparts in the UK, Kit Malthouse, recently did:

“Some companies are simply too big and too dominant. If they are operating like monopolies, then they should be treated like monopolies and dismantled. If a firm controls more than 50% of a market, a breakup review should be triggered automatically. The burden of proof should be on the company to prove it is not behaving anti-competitively. Forced divestitures must be a positive option, not a last resort.”

In writing that, Malthouse goes against decades of economic research that shows concentration is a poor measure of market power—indeed, strong competition can even increase concentration as the most productive companies win market share and benefit from scale economies. That’s generally a good thing for consumers, provided entry and exit remains free.

Such arbitrary rules as proposed by Malthouse also risk unintended consequences. As competition economist Brian Albrecht wrote in response:

“First, the 50% threshold is completely arbitrary. Many markets naturally tend toward higher concentration due to economies of scale, network effects, or other efficiencies that benefit consumers. In industries with high fixed costs and low marginal costs—like software, pharmaceuticals, or telecommunications—larger firms can offer products at lower prices. Breaking them up would eliminate these efficiencies and likely raise prices for consumers.

Second, this arbitrary line-drawing demonstrates the fundamental problem with automatic-review thresholds. A company like Whole Foods would face constant uncertainty about whether they’re approaching a dangerous threshold. Are they competing in ‘premium organic groceries’ (where they would exceed 50%) or ‘all groceries’ (where they wouldn’t)? The answer depends entirely on how a regulator chooses to define the market — something the business cannot control or reliably predict. This definitional gerrymandering means well-run companies must constantly worry about growing too successful in whatever sub-market a regulator might carve out. The uncertainty alone would chill investment and innovation. Why develop a revolutionary product if success might trigger a costly breakup review?

Third, and perhaps most damaging, this policy would create perverse incentives that would actively harm consumers. Companies approaching the 50% threshold would face a stark choice: either deliberately limit growth, raise prices to reduce market share, or face a costly breakup process.”

That’s just the start; Albrecht goes into plenty of detail about the many other things Malthouse gets wrong about competition.

Returning to Australia, a recent ACCC inquiry found that a key reason for the resilience of the Colesworth dominance was our old friend land-use zoning:

“Availability of suitable retail sites is limited by planning and zoning laws, which restrict overall supply and can lead to delays that deter entry or expansion.

Coles and Woolworths have advantages in securing suitable retail sites due to their significant size, reputation and financial resources. As a consequence, their rivals find securing retail sites challenging in competition with Coles and Woolworths.”

One of its key recommendations was that governments should “adopt measures to simplify, streamline and harmonise planning and zoning laws across jurisdictions… [to] reduce barriers to entry and expansion for all competitors”.

In fact, that was the only recommendation (out of 20) that didn’t involve something along the lines of improving pricing transparency, tweaking promotional practices, and supporting community-owned stores; recommendations which are largely cosmetic, because they don’t address the structural factors that led to the dominance—most notably strong scale economies, which is perhaps insurmountable given Australia is a large and sparsely populated country.

Anyway, thankfully Peter Dutton’s deputy Sussan Ley and shadow Treasurer Angus Taylor are much less keen on the idea of forcibly breaking up successful businesses based on a loose and empirically suspect concept of competition. Should Dutton win the election, hopefully the cooler heads—now armed with this ACCC inquiry—will prevail.

The problem with a renewables-heavy energy grid

From the excellent Brian Potter, who in a post covering everything solar wrote:

“[B]oth our storage capacity and our solar PV capacity are subject to diminishing returns. Each additional square meter of panel and kilowatt-hour of storage supplies a smaller and smaller proportion of our overall electricity demand, meaning each additional kilowatt-hour of electricity provided is more expensive than the last. We can supply 25% of our household’s electricity demands with 15 square meters of panels. But supplying 75% requires not three times the panel area (45 meters) but more than five times (85 meters), plus 20 kilowatt-hours of energy storage. And going from meeting 75% of demand to 95% of demand requires roughly doubling the size of the system, to 135 square meters of panels and 50 kilowatt-hours of storage.”

Solar with storage is highly competitive—up to a point. Potter modelled a few outcomes and found that that in the US, you could get to a 50% solar and battery grid share at current residential electricity prices. If solar and battery prices roughly halve from here, that could plausibly move up to 80% without raising power prices.

However, it’s not clear that the constraint today is solar PV and batteries but rather the grid itself—e.g. the poles and wires needed to link it all together, or the fewer hours available for ‘firming’ power sources to recoup their costs. As Potter notes, “utility-scale solar costs in the US have been roughly flat for the last six years, even as module costs have fallen, due to rising costs elsewhere in the system”.

Basically, in a renewables-heavy grid you really need a low-cost ‘firm’ source of power to cover the remaining ~20-50% of your energy needs. That can be coal, gas, or nuclear—pick your poison. But barring a technological breakthrough, a renewables-heavy grid will almost certainly be more expensive than an ‘all-of-the-above’ grid because of the need to overbuild for the most extreme dunkelflaute moments.

Further reading

- This is why the Albanese government cracked down on vaping: “A collapse in tobacco excise has blown a $31 billion hole in the budget bottom line as new documents reveal the federal Treasury was unprepared for the financial fallout caused by vaping and a surge in black market cigarettes.”

- Meanwhile, in New Zealand—where smoking rates have fallen much faster than in Australia—the government is now giving out a “supply of free or discounted vaping products as part of a publicly-funded smoking cessation programme”.

- Vaping isn’t good for you but it’s less bad than smoking: “Vape aerosols share some of those carcinogens and toxins, but generally at much lower levels. Crucially, vaping delivers no carbon monoxide or tar, two of the biggest nasties in cigarette smoke.”

- A new paper by academics at the University of South Australia found that there’s “no link” between international student numbers and the cost of rent in Australia, likely because they have “different housing needs compared with locals”.

- As I predicted, Russia’s war-time honeymoon is over and its economy is now " in freefall as mortgage costs triple and mass layoffs cripple major firms".

- Trump’s trade war, as every trade war has done in the past, is causing US farmers to lose “market share in global agricultural markets”, making the US more dependent on food imports, not less: “The Trump administration should read a 1983 government report analysing the impact of American food embargoes and trade spats in the 1970s and 1980s, under Presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter. The three lessons are crystal clear – and as applicable in 2025 as they were half a century ago. The US became viewed as an ‘unreliable’ world supplier of agricultural commodities; the report found that ‘major countries that compete with the United States in the world grain and soybean markets expanded their production and exports of these commodities so as to capture a growing share of the world trade’; and the US government ‘incurred costs to cushion the adverse effects’ of the trade policies. Rinse, wash, repeat.”

- Electric is the future: “Chinese automaker BYD is turning heads with claims that it’s developed an electric-vehicle platform it says will enable drivers to charge an EV in roughly the same time it takes to refuel a gasoline car.”

- How to regulate artificial intelligence: “Avoid setting up regulations that become a moat protecting incumbents”, and five other “regulatory principles would have the consequence of increasing the pace of AI development while also maintaining safety”.

- Hopefully Trump is the spark that Canada needs to tear down its interprovincial trade barriers: “Tariffs have a dramatic effect, but they’re easy to remove. The issues affecting interprovincial trade in Canada are thornier. This is on full display in premiers’ renewed commitment to eliminate interprovincial barriers by 1 June 2025: except in Quebec (linguistic concerns); excluding food; most First Ministers commit to direct-to-consumer Canadian alcohol sales.”

- Lessons from Ireland’s rise and fall: “Ireland became Europe’s most protectionist country, with imports/exports falling 64%. Protectionism did what it always does: made most people poorer while enriching the politically-connected. Ireland’s isolationism kept it closed and poor. It was a backwater by choice.”

- People really hate living near wind turbines – enough to reduce property values by up to 20% for homes affected by a turbine’s shadow flicker.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!