The wrong way to fix the budget

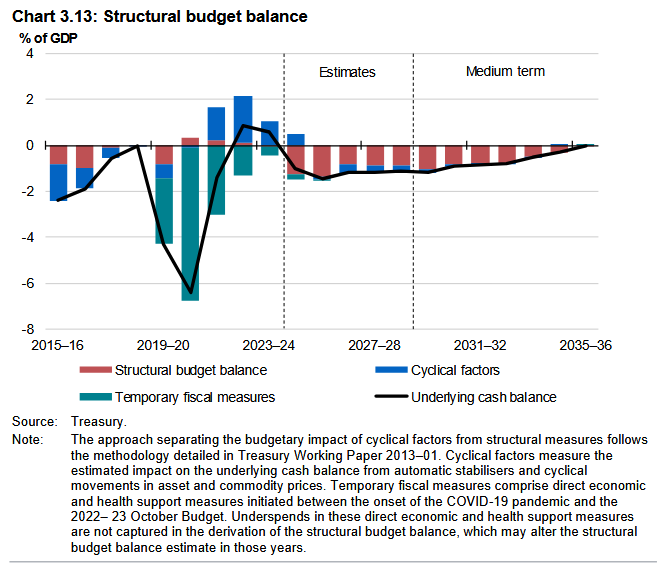

Australia has a budget problem. Basically, it’s in structural deficit, i.e. we can’t even manage to balance the books even when the economy is performing at its potential. You can see it for yourself by scrolling to the last page of the latest budget’s Statement 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook, which includes a chart that actually understates how bad the situation is by making unrealistic assumptions, such as bracket creep never being (partially) returned every several years and that Australia will never again have a crisis necessitating big new expenditures.

The structural deficit can only be fixed with cuts to spending (politically unpopular), repeated bouts of unexpected inflation (difficult with an independent central bank), higher taxes (economically destructive), or by growing out of it with serious doses of economic reform (all but absent in Australia for 25 years).

Of those options, Treasurer Jim Chalmers has decided to start with higher taxes, confirming last week that one of the first items on the new Labor/Greens parliament’s agenda will be to tap the nation’s $4.2 trillion pool of superannuation (retirement funds). Specifically, the the tax rate on “earnings” will move from 15% to 30% on balances above $3m, a threshold that will not be indexed for inflation.

Now, I put “earnings” in quotation marks above because if the plan was just to double income taxes on superannuation balances above a certain fixed level, this wouldn’t be that big of a deal—Chalmers is perfectly entitled to fiddle with tax rates, and it’s not like the country’s taxation settings are anywhere close to optimal.

But the devil is in the detail. As I see it, there are at least four problems with Chalmers’ proposal that have yet to be resolved:

- At its core, it’s not reform but a “tax the rich” redistribution scheme. That may or may not be desirable; Chalmers’ hasn’t even made the argument.

- It’s a breach of trust in government—many people voluntarily contributed to their superannuation funds under the assumption that the rules wouldn’t change.

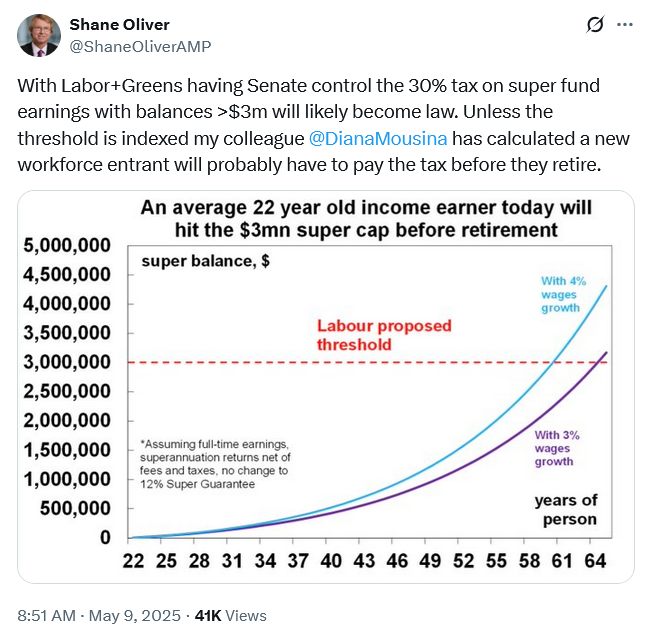

- Not indexing the threshold to inflation means that over time bracket creep will push more and more Australians into paying higher taxes, not just the top 1% of savers.

- Including the unrealised gains from assets—e.g. small businesses, farms, shares—as “earnings” opens up a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences.

Below are some brief comments on each point.

It’s a poorly designed redistribution scheme

There’s nothing wrong with wanting more redistribution, provided you acknowledge the trade-offs: that by focusing on how the pie is divided rather than growing it you will change consumption and savings patterns, and there will be less wealth for everyone in the future.

Chalmers’ superannuation plan is especially damaging is because it’s raising taxes on savings to fund the redistribution. It’s essentially a wealth tax that will reduce the nation’s aggregate savings and investment, which are key engines of growth.

If the goal was for more or better-allocated redistribution among retirees, there are many less distortive ways of achieving that, e.g. removing subsidies for the well-off, tweaking the pension means test, or a simple surcharge on high incomes—all of which are transparent and far less complex than tinkering with a vehicle designed to encourage long‑run saving.

It’s a breach of trust

We’ve all seen the regime uncertainty that Trump has unleashed across the Pacific, which is anathema to savings and investment. Well, Chalmers is basically doing something similar here: Australia set up a system for people to save for their own retirements, made it mandatory, and now they’re looking to take it from people who worked hard and trusted the system—proving that government cannot be trusted.

Sure, today it’s the unrealised gains on ’the 1%’ with balances over $3m. But tomorrow it might be everyone’s unrealised gains from other assets, taxing your home, inheritance, getting rid of franking credits to boost the corporate tax take (effectively double taxing people, but Chalmers has shown he’s not averse to that), increasing the bank levy, or <insert everywhere else there’s a large amount of ‘untapped’ wealth or income that can be taxed away>.

You get my point—such uncertainty will reduce the incentive for saving and investment, and while it won’t hurt the economy today, it will reduce the long-run rate of growth, so over time we’ll all be poorer because of it (growth compounds!).

It’s dishonest

The reason Chalmers hasn’t indexed these changes to inflation is because he wants to catch more people over time; to tax people by stealth. Rather than doing the right thing and indexing all other taxes, he’s even using the mess that is Australia’s tax system as justification for not doing it with this one:

“There are a number of areas in our tax system where thresholds aren’t indexed, where they are changed from time to time by governments, and I would expect that to be the case again.

It would be a strange assumption to assume that in the next 30 or 40 years nobody ever changes the threshold. That doesn’t happen in other parts of the tax system, and it wouldn’t happen in this part of the tax system over a period that long.”

For those who believe the Treasurer that the threshold will be changed in the future (for today’s 18 year olds, $3m today will be roughly the equivalent of $700k when they retire), let me direct you to the Division 293 tax, the threshold for which was lowered in 2017-18 and now captures significantly more people than when it was introduced— excluding most politicians and high ranking bureaucrats, of course.

It’s just dishonest policy-making that reduces transparency and accountability, and undermines the tax system’s fairness and efficiency.

It’s loaded with unintended consequences

There are very few taxes out there that are worse than taxing unrealised capital gains. The whole process is complex, subjective, and just all around messy.

- It will be a compliance nightmare that invites costly disputes, legal challenges, and potential manipulation, all of which undermine the tax system’s fairness and efficiency.

- It will remove a source of funding for Australia’s venture capital scene, because start-ups take a long time to turn a profit and can be difficult to value. Likewise, all illiquid assets (e.g. property, private equity) will require annual valuations, so people will change their behaviour by favouring liquid and easy to value investments over physical ones like farms or factories—or risk being forced to sell at sub-optimal times.

- It will discourage saving and investment and with the lack of indexing, eventually confidence in the superannuation system itself, because the repeated taxation of unrealised gains compounds the tax rate, reaching punitive levels over time.

- It will cause “bunching” at the threshhold, and force individuals into socially wasteful alternatives to superannuation such as overcapitalising on their tax-exempt principal place of residence, sheltering assets offshore, or setting up administratively burdensome investment companies and family trusts.

- It might even worsen the structural budget deficit in the very long-run by incentivising present-day consumption over contributing to superannuation (i.e. saving) and discouraging lifetime work (why work above a certain amount when the government will tax it all away), thereby increasing the reliance on public pensions—not ideal with an aging population!

All up, it’s an ill conceived policy from a Treasurer who is proving to be unserious about fixing the most challenging economic problems that Australia faces. While Chalmers is right that the current superannuation model is a mess and in dire need of reform (or a complete do-over), this plan is nothing but a poorly disguised money grab wrapped up in a populist veneer designed to convince enough people that it’s no big deal.

My message to Chalmers would be: by all means, raise the superannuation tax rate and get rid of the tax exemption for investment earnings post-retirement for those with large balances. But don’t tax unrealised gains, index any thresholds to inflation, and be up-front and transparent about what it is you’re doing and why. Simply stating that the budget is “unsustainable” as justification doesn’t cut the mustard when there are plenty of other more efficient and equitable ways to get the budget back on track than what you’re planning to do to superannuation.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!