There ain't no such thing as a free lunch

I never imagined I’d have to write a post with this title; surely, I thought, anyone who makes it to a top political office in this country has at least the most basic grasp of economics. And if not, surely – surely! – one of their many advisors would.

But then back when I started writing, Queensland’s Premier Steven Miles wasn’t in a position to come up with policies that might affect everyone.

So, here we are. Just ten days out from the Queensland state election, and Steven Miles – who has been in the role for just nine months – has surely set the record for the number of irresponsible policy announcements per day in office (with apologies to “Red Ted” Theodore).

Most recently, Miles pledged to give every primary school student in the state “free” lunches:

There’s a lot to unpack here, starting with the claim that it will be “free”. Anyone who has done even high school economics knows that one of the first rules of economics is TANSTAAFL, or there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.

It means that for every decision involving scarce resources – e.g. goods, money, time – there’s a trade-off that must be made. So when Miles says lunches will be “free”, what he really means is he’s making a trade-off, but is not telling us what he’s giving up.

In this case, it appears that he’s effectively sending the bill to all children by adding $1.4 billion to the state’s debt over four years. That new debt will increase the burden on that generation through higher than otherwise future taxes.

There are a bunch of other second-order effects too, such as crowding out private investment as government borrowing competes for limited financial resources, the deadweight costs of the future taxes needed to pay for the scheme, and adding to demand – this is effectively a cash transfer to a group of households – during an inflationary cost-of-living crisis.

There are also equity issues. While there is indeed evidence that having well-nourished students is good for “kids, teachers & parents”, Miles’ scheme isn’t even remotely targeted. It’s effectively a transfer, with the $1,600 “saved” by households of primary school children coming at the expense of the childless and households without kids in primary school.

The problem with a blanket, untargeted scheme is that it’s massively overpaying to achieve its stated benefits. Estimates from Australia puts the prevalence of food insecurity at around 5%, so while they will be supported, it’s also diverting resources to the 95% of households that don’t face food insecurity. Those funds could probably be better used elsewhere, or just not borrowed to begin with, avoiding the deadweight loss of future taxes and other distortions.

If Miles was serious about helping the kids who would benefit the most from state-sponsored lunches, he could have just copied the US National School Lunch Program, which reimburses the parents of low-income households for the cost of a lunch. It has its share of problems – some communities “identify all their students as low income, even students from high-income families” – but is at least an attempt to target households that actually need it.

I’m reminded of a quote from the great Thomas Sowell, who once wrote that:

“The first lesson of economics is scarcity: There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics.”

If he didn’t write that back in 1993 then I’d have sworn it was directed at Steven Miles, who clearly knows his politics but is completely vapid on all matters economics.

Miles’ long list of policy misadventures

Shortly after Steven Miles became Premier, I wrote an essay about how, after just a month in the job, Miles already claimed to know better than the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), and had announced a series of housing policies that risked making the state’s housing situation worse.

In the eight months since then he has not slowed down. Here’s the list of notable policies Miles has either passed or has committed himself to, were he to win the election (I will inevitably have missed some):

Passed policies

- 50-cent capped fares on public transport, which is effectively a cross-subsidy from regional Queensland to city folk.

- A $1,000, non-means tested energy rebate for households, which will add to demand and therefore inflation during a cost-of-living crisis.

- Kids sport vouchers for up to $200. It will be interesting to see if this increases participation at all; if not, it’s pure demand stimulus, as parents have $200 to use on something else.

- Cutting the car registration fee by 20%, effectively transferring some of the public transport subsidy back to drivers (minus the deadweight loss).

- Raised the first home buyer stamp duty concession and doubled the grant to $30,000, which in a market with inelastic supply will almost entirely be captured by existing owners.

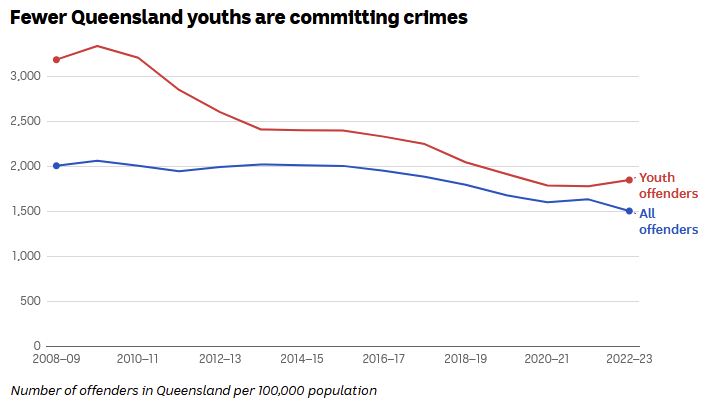

- A raft of law changes and $1.28 billion in funding to “crack down” on crime, despite no evidence that crime has risen.

Proposed policies

- Fund 50 new bulk-billing GP clinics, which the state’s Medical Association said does “not truly understand the operational costs of a general practice. We do not have an infrastructure shortage — we have a workforce shortage”.

- Create 12 state-owned petrol stations, and ban petrol stations from raising prices by more than 5-cents a day. If passed, expect shortages during periods of global instability and volatility.

- Establish a new state-owned energy provider to replace… the existing state-owned energy provider, Ergon, which already services 97% of Queensland.

- Spend $700m duplicating the Bribie Island Bridge (~$34,000 per resident on the island), which the state transport department said was unnecessary for the “foreseeable future”.

In addition to the above, Miles has effectively ‘poison pilled’ the Budget for the next government by striking sweetheart deals with numerous unions, including one that will see “the minimum pay for the average construction worker on civil projects [rise] to more than $200,000”, and another with the Electrical Trades Union that “could drive up costs for the power companies by more than 30%”.

Our profligate states

I’ve been especially hard on the Steven Miles and the Queensland government in this post because Miles has been splashing cash on everything under the sun in a desperate bid to win next week’s election. That’s not to say the state Coalition is much better; it has also pledged to splurge on its own spending promises, and may also be hiding extra baggage in the form of a rumoured abortion ban bill.

Despite these concerns, the Coalition remains favoured in polls and on betting markets, so barring some huge scandal in the next ten days, many of Miles’ more extreme proposed policies will – thankfully – never see the light of day.

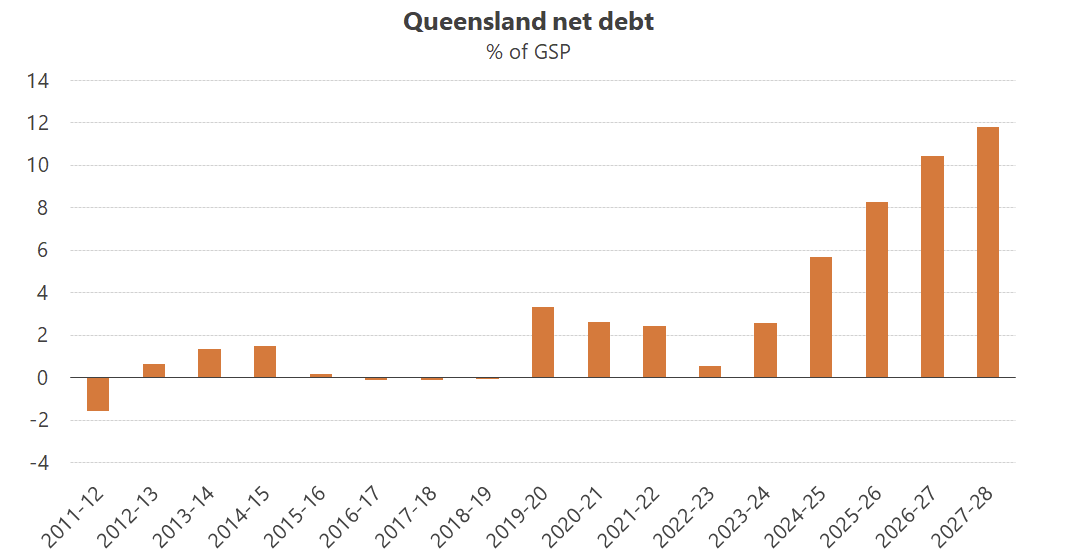

But Queensland is not alone in its fiscal profligacy; no, all of our states have been governed relatively poorly over the past several years. During a period of high inflation and low unemployment they’ve been busily ratcheting up spending and debt, which is precisely the opposite of what even relatively interventionist Keynesian economic textbooks would recommend:

These 2024-25 budget estimates do not take recent spending commitments into account.

These 2024-25 budget estimates do not take recent spending commitments into account.

To be clear, this level of debt is certainly manageable. However, it matters how you’re accumulating it, as that will affect productivity, growth, and the ability to service it without raising taxes ( r minus g).

But when the new debt is being spent on programs like untargeted, non-means tested school lunches for every kid – which Miles said he would “want to consider expanding” to older cohorts because “in future years, you will have kids who have only ever known [free] school lunches” – it’s likely to reduce future productivity compared to other uses of those funds, including not borrowing it in the first place.

So, it’s a problem that total state debt is on track to triple by 2028 from pre-pandemic levels:

“The biggest change [since the budget] occurs in Queensland, where a large uptick in infrastructure spending and pre-election cost-of-living handouts mean debt could end up more than $10 billion higher by 2027 relative to pre-budget projections.”

Unlike in other countries, our states have “no firm fiscal rules”, but still benefit from an implicit guarantee from the Commonwealth, creating “a textbook collective action problem”:

“Each state government in isolation has little impact on the macroeconomy, but together they add to inflationary pressures by competing for the same limited pool of engineers, labourers, and tradespeople.”

A report by Westpac’s Pat Bustamante forecasts that combined state and federal public spending will “reach 28% of real GDP by the end of 2025, from its pre pandemic average of 22.5%”, which he says is responsible for at least some of the country’s current productivity crisis.

Bustamante adds that there are other problems with an enlarged public sector, including the pressure it’s putting on inflation by “bidding away resources from the private sector”.

Deficit states like Victoria are already borrowing “merely to meet interest outlays, creating a vicious feedback loop”. That crowds out not just the private sector but also other public spending that now can’t be undertaken because there’s nothing left after operational and interest costs.

Finally, when – not if – the next crisis emerges (e.g. war, pandemic, recession), all levels of government will already be fiscally constrained, and the private sector that ultimately pays for everything will be smaller relative to the total economy.

In other words, because the government is borrowing for things like “free lunches” today, it won’t be able to borrow for much-needed support when it truly matters for the majority of the population.

There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!