There is no next China

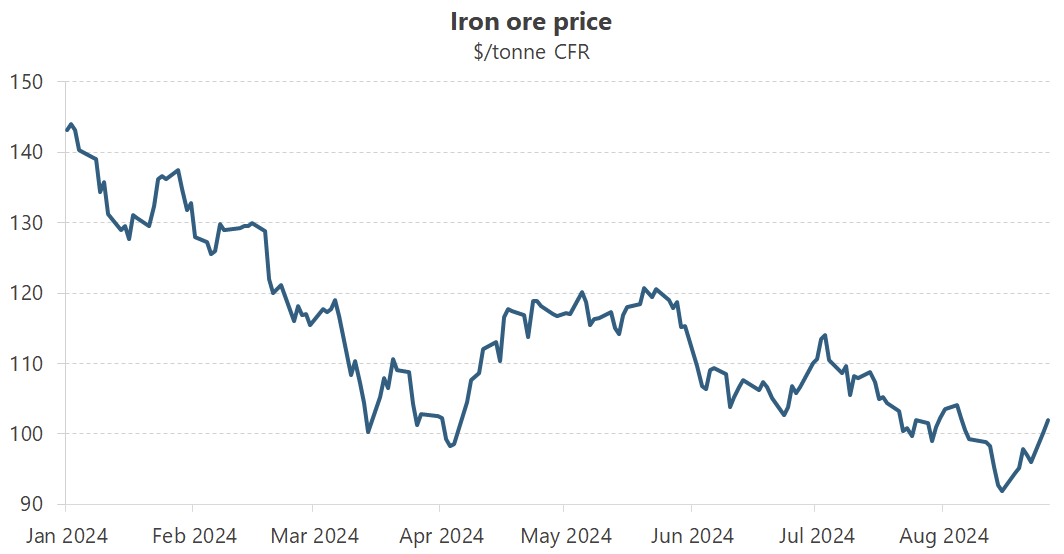

Iron ore has been in the news a lot lately for all the wrong reasons. Last week, Australia’s Treasurer Jim Chalmers warned that softening prices for the key steel-making ingredient could wipe out $3 billion of federal revenue over the next four years.

I’m not entirely sure how he calculated that, because in the Budget Treasury undercooked its iron ore price forecast by assuming it would fall to $US60/tonne by the end of the March quarter 2025 (excluding freight, so really that’s around $US70/tonne). In all likelihood, the Budget would have had a price for August 2024 below current spot prices, meaning we’d need prices to fall quite a bit from here to start wiping out projected revenue.

Anyway, the good news is that since Chalmers issued his warning, iron ore prices have rebounded to just above $US100/tonne. Barring a disaster between now and March 2024, iron ore looks like it’ll create some upside risk to the next Budget.

The bad news is that some analysts are predicting prices are going to remain a lot weaker than we’ve seen over the past couple of years:

“Goldman Sachs says ‘only 1% of Chinese steel mills are currently profitable. In the absence of a hot metal output recovery, continued strong iron ore supply means that we maintain the view that iron ore needs to remain below $100/t’.”

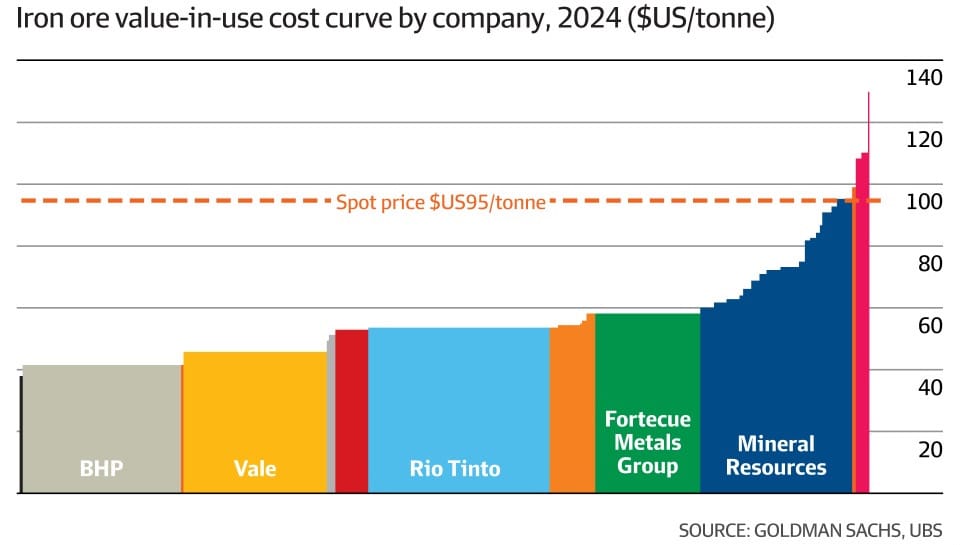

Prices sustained below $100 would be bad news for the federal and WA Budgets, and also some of our higher-cost mining companies:

The above chart shows value-in-use, which adjusts the cost per tonne for the quality of the ore. That’s important, because it means lower-grade producers like Fortescue, which claims to be “the world’s lowest-cost iron ore producer”, has its costs weighted appropriately.

If iron ore prices fall much further the most marginal mines will eventually shut down, helping to stabilise prices. For example, Mineral Resources has already announced that its relatively high-cost Yilgarn iron ore will cease operations at the end of this year, having banked a cheeky couple hundred million in royalty relief from the WA government over the past five years (a perfect case study in why tax incentives for mining are generally a bad idea).

So, barring a catastrophe in China – more than just a winter, but an ice age so bad that even the Chinese government refuses to step in as it almost always does in these “winters” – iron ore prices shouldn’t collapse to levels where the federal Budget is too pressured.

Still, lower iron ore prices would mean fewer iron ore ‘bonuses’ in the Budget every year. So it was no surprise to find out that Chalmers is reportedly preparing for a trip to China in September, because he’s likely to “be extremely anxious about the state of the Chinese economy – especially the steel industry – and will be keen to get a first-hand sense of what is going on”.

Fair enough; not only is the Chinese economy in a bit of a flux, but globalisation itself looks to be evolving in ways that will have serious implications for Australia’s future. Not in one, two or five years – i.e., the Budget forward estimates – but in ten, twenty or thirty years.

The great rewiring

Last week I came across a recent report by Lazard Geopolitical Advisory, which covered this issues – the “rewiring of supply chains” away from China – in some depth. It didn’t just discuss the outlook for China, but also its possible replacements: India, Vietnam, Mexico, Poland, and Thailand.

The long and the short of it is that China isn’t going anywhere, as its infrastructure is just that good – and by infrastructure I don’t just mean the road, rail and port network, but its “effective, skilled labour force and competitive infrastructure and trade links”:

“[I]in aggregate, China is largely undiminished as an industrial and manufacturing powerhouse. Subsidies appear to be fuelling a shift away from products that helped create the Chinese miracle of the 1990s and 2000s, like textiles and toys, into higher value-added products like computers and electric vehicles, driven by domestic Chinese firms. Geopolitical tension and economic struggles must therefore be weighed against the reality that China is still the largest global exporter of goods and may succeed in its pivot to more high-tech products.”

What has dried up is foreign investment, which declined at the end of 2023 for the first time in decades. But there are still a lot of foreign companies already in China, and with China ramping up its own domestic investment (as ill-advised as that may be), it should remain a steady destination for Australia’s commodities.

But in the longer term, the foreign investment that is no longer calling China home has to go somewhere. Lazard don’t think it’ll go to a “next China”, but rather “China plus many”, including Thailand, Poland, India, Mexico, and Vietnam.

Enter India?

Unlike China, which still has just about everything going for it other than politics, all of the possible replacements have significant disadvantages. For example:

- Thailand has a productive workforce and relatively low-cost labour—but it has a higher median age than those of other nations, suggesting future labour force pressures.

- Poland is the only nation in this analysis with better infrastructure than China’s, but Poland suffers from water shortages that create manufacturing pressures and has an aging population with immigration reform unlikely.

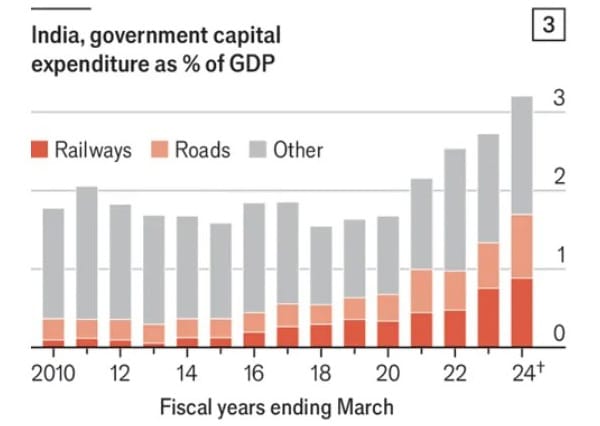

- India, with its sizable population, has demographic tailwinds, but its workforce will need further investments to raise productivity.

- Mexico has water shortages and energy production challenges, but its proximity to the US makes it a compelling investment destination.

- Vietnam has strong trade links and affordable labour, but its labour force has low productivity, and it has growing political challenges.

Lazard notes that Vietnam and India would be good options if they weren’t so far behind China in terms of infrastructure – it’s going to take many, many years before they can ever hope to take even a fraction of China’s business.

For example, the average speed on Vietnam’s roads is a mere 50km per hour (and it’s not that slow because of speed limits!). In India, logistics as a share of manufacturing costs are double what they are in China. It’s trying to improve that, but it’s behind schedule and over cost on nearly half of its ongoing major infrastructure investment projects.

Still, from an Australian perspective the best option suggested by Lazard is India. It’s big, is a Commonwealth nation, and is within our geopolitical sphere.

If India were to start picking up some of China’s slack, we would also keep the competitive advantage of distance. For example, it costs two and half times as much to ship a tonne of iron ore from Brazil to China, even with its gigantic 400,000 deadweight tonne fleet of Valemax ships. If we had to start shipping goods to Mexico or Poland, a lot of our mining companies might find it prohibitive compared to the current model of just sending everything to China.

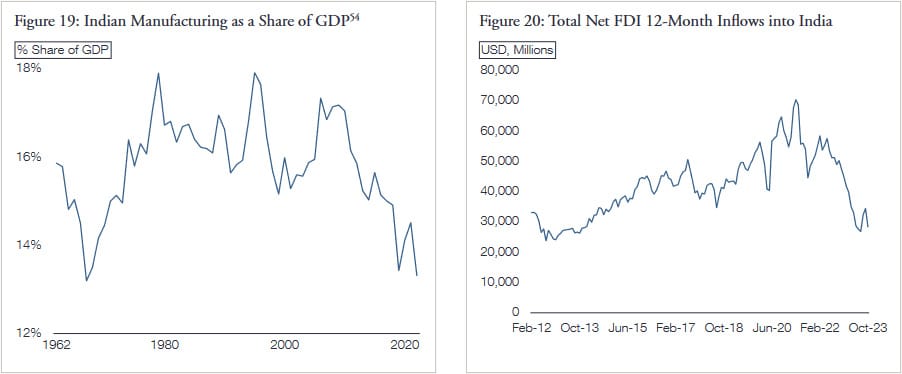

But India’s economy might also just be too structurally different to seriously threaten China’s status as the world’s manufacturing hub:

“India’s vision of itself as a manufacturing hub for exports clashes against the reality that close to 40% of its exports are in services, like IT and tourism, and a further 15% is in agriculture and precious metals.”

Foreign investment in India is no higher than it was a decade ago, and its manufacturing sector as a share of GDP has fallen back at 1960 levels:

It’s not just foreigners, either; domestic firms are also unwilling to invest in India because they deem the risks are too high. It’s perhaps why the country is dominated by a few conglomerates owned by billionaires with friends in high places – those who are able to use the political apparatus to insure themselves from policymaking uncertainty, as well as secure themselves protection such as import barriers.

China won’t give it up

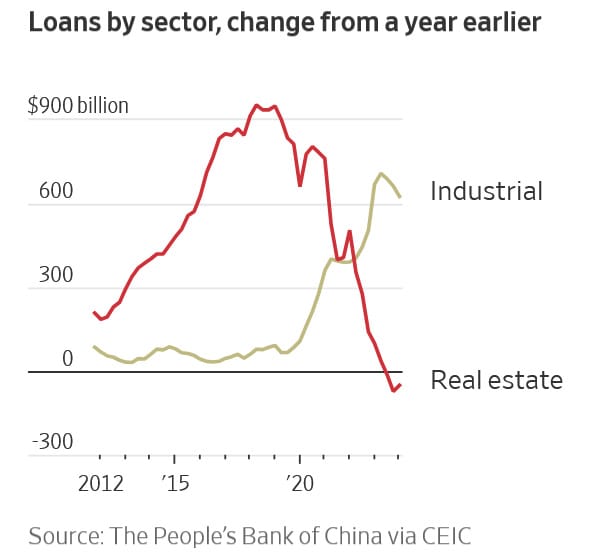

The final hurdle to a “next China” is that Xi Jinping is determined not to give up the title of world’s manufacturing hub. In recent years, he has been actively directing Chinese investment into industry and away from real estate:

Was a divestiture from real estate necessary? Absolutely. But Xi is just propping up another bubble to replace the last one, with the new industrial production exported to the rest of the world. And he’s doing it with even more debt, effectively subsidising our consumption at the expense of Chinese households:

“China’s economy is buried under a great wall of debt and Xi Jinping’s answer is to add more bricks. The president has sanctioned an extraordinary programme of borrowing by the central government to steer the $18 trillion behemoth to ‘high quality development’.

…

The central government’s balance sheet remains tidy for now. Its outstanding borrowings amounted to 24% of GDP at the end of 2023, the International Monetary Fund estimates, among the lowest of major economies. If all else remains equal and China issues special sovereign bonds to the tune of 1 trillion yuan each year for the next decade, its borrowings would rise nearly 8 percentage points to almost 32% of last year’s GDP, Breakingviews calculates.

The problems stack up elsewhere, however. Explicit local government debt amounted to another 31% of GDP by the end of 2023, per the IMF, LGFVs account for a further 48%, and other government funds another 13%, bringing the augmented debt up to 116 trillion yuan, about $16 trillion, or 116% of GDP – a 35% increase on 2018, the IMF calculates.

Corporate debt adds another 123% of GDP, much of it issued by state banks and owed by state-owned enterprises, plus there’s household debt at 61% of GDP, per Fidelity, which calculates gross debt at over 300% of GDP.

Xi Jinping is 71 years old. The special bonds he’s issuing have maturities of up to 50 years. I think it’s safe to say that by the time they mature, he won’t be around. He’s basically buying time – to “establish the new before breaking the old” – hoping that his latest adventure into state-directed investment will pay off, rather than ending up like so many abandoned apartment buildings, railway stations, and Belt and Road projects that came and went before.

Whether his plan pays off will go a long way to determining if China can avoid a debt crisis. But I’m also worried he has more on his mind than China’s economy:

“China has suffered from persistent overcapacity in the past, at times raising ire from its trading partners for depressing global prices for steel and other goods.

In 2015, Xi entrusted his economic czar at the time, Liu He, to implement reforms that led to closures of many small and privately owned steel mills and other businesses. For a while, it seemed as if Xi and his economic team were ready to finally tackle overproduction.

But as tensions with the US escalated in recent years, and China’s economy weakened, Xi’s views changed, Chinese policy advisers say. He grew more concerned about ensuring China could produce everything it needed in the event of a conflict with the US, and became less sympathetic to Western complaints.

If that sounds familiar, it should: it’s the model Russia adopted back in 2008.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!