Thursday Thinkers (12/24)

Yes, I’m aware it’s not Friday. But it’s a very long weekend and hopefully none of you will be in the office tomorrow or on Monday, so I’m sending this week’s extra-long Fodder out a day early and calling it Thursday Thinkers instead. Enjoy!

1. A bit too shocking

Way back in January (can you believe it’s already Easter?!) I wrote an essay on the arrival of Argentina’s new President, Javier Milei, who quite literally wanted to take a chainsaw to the country’s corrupt, overly-regulated and stagnant economy. I concluded that “the odds of Milei pulling this off and breaking Argentina’s century-long slump are low. The country’s bonds remain deeply distressed, trading at 30-40 cents on the dollar, the peso continues to fall on the black market, and its largest labour union has called for a disruptive nationwide strike on 24 January”.

It’s now a bit over three months into Milei’s Presidency, so I thought it would be worthwhile providing an update. Here’s Nicolás Cachanosky with the bad news:

“Milei has only faced setbacks in Congress and in the judiciary, which suspended the labour reform chapters in his necessity and urgency decree. The increasing animosity with Vice President Victoria Villaruel does not help. Similarly, his openly aggressive behaviour towards those legislators who hold the votes he needs only increases the level of uncertainty.

The legislative constraint should not be ignored. Before the elections, it was expected that he would be politically weak in Congress, given his political party only has a small number of seats. After the election, this expectation is now confirmed.”

Milei’s path to success is now even narrower than it was when he came to power. Fiscal austerity has come about by reducing “pension payouts and an almost total halt of public works”, and persistent inflation (which he inherited) has eroded real incomes, contributing to a rise in the poverty rate from 40% to 47% in one year.

The “$9 billion increase in international reserves isn’t a surge in confidence. It’s the result of printing pesos to buy the dollars and then issuing debt at high interest rates to sop up those pesos”.

For now, opinion polling shows voters are split down the middle – life in Argentina really was that bad before Milei was elected, so it’s hard to blame him for it. And he still " has a chance because Argentina lives on illusions":

“President Raúl Alfonsín managed to represent the joy of the democratic return in the 1980s after the bloody military dictatorship; Carlos Menem brought economic stability in the 1990s after the hyperinflation, and Néstor Kirchner was able to overcome the power vacuum after the 2001 implosion.”

Whether Milei can keep public opinion on side is the big, unknowable question, and will determine whether or not he succeeds in breaking the cycle of economic misery in Argentina. As I wrote in January: “Argentina doesn’t have a simple Band-Aid that needs to be ripped off; it needs entire limbs cauterised. That will be painful, and not just to regular voters but also to the elites to whom Argentina’s policies and institutions were designed to transfer wealth.”

2. RIP The Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment, a period of free expression that saw breakthroughs in literature, philosophy, economics, sociology, anthropology, mathematics, science and medicine – we owe a lot to the thinkers of 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland – “will die on April 1st 2024, exactly 327 years, eight months and 24 days after the incident that provoked it”.

That’s according to the pseudonymous C.J. Strachan, who notes that the forthcoming Hate Crime and Public Order Act (Scotland) 2021 “will criminalise speech and opinion deemed ‘hateful’ even if spoken in the privacy of your own home”.

Strachan worries that by criminalising “saying the wrong thing”, the Act will take Scotland back to the pre-Enlightenment days, where:

“On January 8th 1697, Thomas Aikenhead, a 20 year-old student, was marched the two miles from the Old Tolbooth Prison on the High Street to a windswept sandy hillock just to the west of the causeway that crossed the marshes between Edinburgh and the port town of Leith, known as Gallow Lee. Surrounded by the pious prayers of the clergymen of the Kirk (the Church of Scotland), Thomas was hanged by the neck until he was dead.

What was Thomas – a murderer? A rapist? Was he one of Edinburgh’s notorious ‘Resurrection Men’? No. Young Thomas’s crime was that in an Edinburgh tavern on Christmas Eve 1696, he had a drink and went on a rant offending the Church and its stranglehold on Scottish culture. He was reported, arrested and tried: ‘The jury found Aikenhead guilty of cursing and railing against God, denying the incarnation and the Trinity and scoffing at the Scriptures’.”

Australia has had a similar – but not quite as awful, because our dinner tables are still sacrosanct – law on its books since 1995: Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, which makes “it unlawful to do an act in public that is likely to offend, insult or humiliate a person or group of people based on their race, colour, nationality or ethnicity”.

The word “offend” is of particular concern, with the Australian Law Reform Commission finding that it “unjustifiably interferes with freedom of speech by extending to speech that is reasonably likely to ‘offend’… and may be susceptible to constitutional challenge”.

More recently, our government has undermined our freedom of expression by attacking privacy, through laws such as the Telecommunications Legislation Amendment (International Production Orders) Bill 2020 and the Surveillance Legislation Amendment (Identify and Disrupt) Bill 2020, which give authorities (not just in Australia) broad access to communications data, including the ability to “access devices and alter or delete data”, and to covertly control people’s social media accounts to gather evidence of a crime.

But despite all that, it could be worse. We could be Scotland. Or Canada, where the government may soon pass “punitive measures that they would have a chilling effect on speech that is fundamentally incompatible with the freedoms we expect in a Western liberal democracy”.

3. How to regulate AI

We know that the Australian government has, so far, taken a ‘wait and see’ approach to AI regulation, so far only releasing an interim report on safety. The report was more or less the right approach, looking at risk and " how AI might be misapplied, for example using experimental programs in self-driving vehicles".

So I was happy to see that Dean Ball, the senior program manager for Stanford’s Hoover Institution State and Local Governance Initiative, had a featured essay in the quarterly National Affairs journal titled How to Regulate Artificial Intelligence. It is more or less aligned with what I would consider the correct approach, namely that we should use existing rules rather than attempt to craft “a new regulatory framework from first principles”:

“Rushing to enact any major set of policies is almost never prudent: Witness the enormous amount of fraud committed through the United States’ multi-trillion-dollar Covid-19 relief packages.”

That includes not blaming the creators of AI for any and all harms caused, as at the end of the day there’s always a human at the other end (large language models are not even on the road to sentience, despite what AI doomers claim):

“The crux of the matter is that AI will act as extensions of our own will, and hence our own intelligence. If a person uses AI to harm others or otherwise violate the law, that person is guilty of a crime. Adding the word “AI” to a crime does not constitute a new crime, nor does it necessarily require a novel solution.”

Ball notes that the US – and I’d add Australia, too – “has a robust set of principles, judicial precedent, and laws that govern the liability of firms for the harms caused by their products in the real world”.

We don’t need a completely separate playbook for AI, even if some of those existing rules “will have to evolve”. But we should definitely avoid destroying something that could have immense economic value before it’s created:

“There is thus a future to hope for — not simply one to fear. To forget this is to lose faith in the process of tool-building, innovation, and technology diffusion that has undergirded almost all material progress. If we forget this — if we lose hope and succumb to fear — regulation that causes stagnation in technological progress will seem tolerable, perhaps even desirable. The crucial balance to strike, then, is between hopeful optimism and candid recognition of the stark challenges we face with this and any new general-purpose technology.”

You can read Ball’s full essay here.

4. Bowen’s backdown

Around a month ago, shortly after Energy Minister Chris Bowen announced his new vehicle emission standard requirements, I asked whether “we have no original ideas in this country?”

The reason I posed that question was because those standards were basically a direct copy of US President Joe Biden’s version announced a year earlier – noting that the US has had some form of emissions regulations in place since 1975, and Biden just tightened it.

Well, last week Biden announced his updated, slightly less strict vehicle emissions regulations. So what does Bowen do? Exactly the same:

“The federal government will water down proposed carbon emissions laws for vehicles, as it seeks to appease auto makers who feared it would push up the price of some cars by thousands of dollars.

…

The changes will shift some car models from the stricter emissions limit for passenger vehicles into a softer standard for “light commercial” cars, meaning cars like the Isuzu MU-X and Ford Everest will no longer have to meet the strictest fuel economy rules.”

Bowen may not have wanted to; rumour has it that Albo himself “stepped in to overhaul Labor’s fuel-efficiency standards plan amid concerns stakeholders are being carved out of policy negotiations across government portfolios and forced to sign nondisclosure agreements banning them from speaking publicly”.

But regardless how the political sausage was cut, any watering down of Bowen’s plan, which is economically much more damaging than almost any other emission-reduction option available to him – including a simple fuel tax – is a win for Australian consumers. Even if, in this case, it might mean more utes on our roads, just as the watered-down version of the original US rules were a reason Yank Tanks proliferated in the States.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

It’s time for fiscal rules – Our states like to cry over the GST distribution and warn about “going into further debt”, yet the real problem is that they’re addicted to spending. If they can’t rein it in, then perhaps we need some fiscal handcuffs to force budget discipline before next crisis hits.

6. The limits of the “push” strategy of technological development

Governments, especially our current federal government, love to talk about a “new approach” to industrial policy:

“Through government investment and doing more to get private capital flowing towards our priorities effectively and efficiently.”

But just because something is a priority and receives private sector buy-in, doesn’t mean it will work out all that well. Enter supersonic transport (SST), which never happened “though not for lack of trying”. That’s from Brian Potter, who provided an interesting history of SST from the late 1950s to today:

“Since the late 1950s, there have been numerous plans to build a supersonic airliner. Most of them never got past the planning stages, and only two – the Soviet Tu-144 and the Concorde – were ultimately built and entered commercial service. Neither the Tu-144 or the Concorde were a commercial success, and today there are no supersonic aircraft in commercial service. Modern airliners fly at roughly the same speed as Boeing’s first jet airliner, the 707.”

Governments in France, Russia, the UK and US all invested “billions of dollars”, in partnership with local business, in what amounted to some of “the largest commercial failures in aviation history”. Here’s how Boeing’s wooden prototype looked:

Potter concludes that:

“The US, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union spent billions of dollars and millions of man-hours in an unsuccessful attempt to continue the trend of increasing commercial air travel speeds. The fundamental physical constraints of supersonic flight have made it inherently noisier and more expensive than subsonic travel, which combined have doomed most commercial efforts, regardless of how many dollars were thrown at the problem. We saw a similar phenomenon with titanium, which despite its abundance, its useful physical properties, and expectations that it might displace steel or aluminium, remains comparatively niche. Despite huge government investments, it remains a comparatively niche material because of fundamental physical constraints that make smelting and processing it expensive.”

Governments can use taxes, subsidies and regulations to speed up progress in areas they’ve deemed important. Potter notes that solar and wind are good examples, where government incentives helped get them “far enough down the learning curve that they have become one of the cheapest sources of electricity, and they’re still getting cheaper”. But success is by no means guaranteed, and “some barriers are too big to be pushed through by sheer force of will”: governments need to be careful not to fall for the sunk cost fallacy, and to be vigilant about cutting off pet projects that are going nowhere, regardless of how many ‘strategies’ they’ve published.

7. How not to fix housing

You may have heard of a new book by Australian economist Cameron Murray called The Great Housing Hijack. As you might expect from the name, it was critical of our housing market. But alas, this one needs to be filed away under the category of misdiagnosing the problem and having no hope of solving it:

“Murray says developers will only ever build a limited number of homes at a time, regardless of planning permissiveness. He argues they will refrain from flooding the housing market. Instead, he says, they will often prefer to just hold on to land, keeping the option of developing it in future.

This claim is based on shaky research. Murray’s model assumes individual land owners have pricing power: if they build too many homes at once, they will undercut their own prices. His analysis uses data on just eight developers, who built 9% of new homes over the period studied.

In fact, the construction sector is not highly concentrated and the urban infill market has many players, so each individual developer has little market power.”

Greens spokesperson for Housing and Homelessness, Max Chandler-Mather, must have read Murray’s book, because he has also convinced himself that there’s a “monopoly” of private developers that needs government competition to “break” it, and that it’s “just not true” that land use zoning is even part of the reason houses are so expensive.

The problem people run into when they start by misdiagnosing the problem is that their solutions will often make things worse. That’s the case here, too, with Murray’s preferred policy option to rip up the housing market, replacing it with “a scheme called HouseMate”, which is essentially a housing lottery:

“The federal government would buy or repurpose land, build homes, then sell them at a discounted price to Australians who do not own property.

The sale price would cover only the construction cost, not the cost of land, so it would provide a big subsidy for the people lucky enough to be chosen. Buyers would get to enjoy living in a discounted home, and could resell (to others eligible for HouseMate) after five years of ownership, pocketing most of the gains. But the catch is, there would only be a limited number of places available each year.

To build the homes, Murray suggests the government could compulsorily acquire sites.”

Goodbye private property rights, hello a government monopoly on land. That can work (look at Singapore), but it’s a lot easier said than done in a country with very different legal and cultural norms such as Australia. On this, I’ll give the final word to the Grattan Institute’s Baldwin and Coates:

“We do not need grand lotteries with catchy names in housing policy. Despite the distractions and debates, we already know what needs to change… [we need to] encourage the states to reform land-use planning rules to get more homes built, the only real long-term fix to our housing woes.”

8. Our happiness, ranked

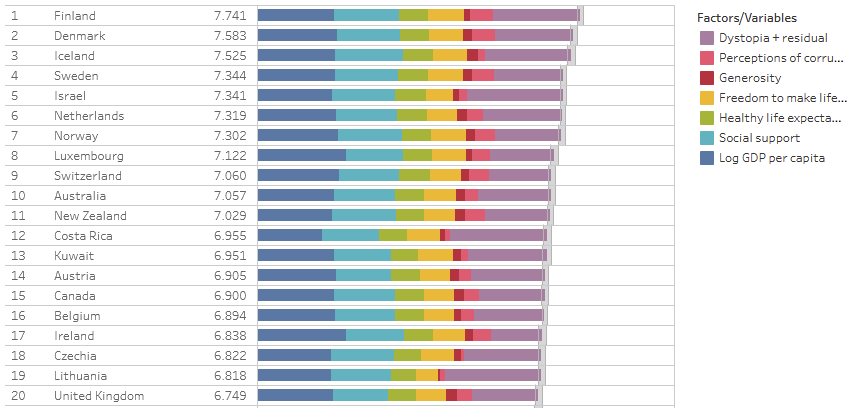

Social scientists love to measure everything, so why wouldn’t there be a global happiness index? If you were curious, here are the March 2024 rankings:

You’ll notice Australia finished in the top 10 (just) – good for us! But as with any aggregate, there could be some hidden gremlins. In this index, it appears that our young people (aged under 30) are not nearly as happy as we are overall, ranking 19th in the world. In fact, from what I can tell one of the reasons we scored well is because we frequently donate to charity and have relatively low corruption.

Yay, I guess, although by scoring well in those it means we’re lagging in growth, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, and social support. One might plausibly argue that those are more important, but that’s a value judgement for someone else to make.

There’s also an issue with the methodology. As Elaine Schwartz has documented, it uses the Cantrell Life ladder, which is a survey where people “consider the difference between what you have and what you could have”.

In wealthy, relatively capitalist countries such as Australia, there can be quite a large gap between those at the bottom of the ladder and those at the top. Young people, because they haven’t been working much (or at all), are almost always near the bottom. Whereas someone living in a place where all the tall poppies get cut down might perceive being closer to the top than someone just starting out in Australia. So writes Schwartz:

“If your aspirations (and imagination) are limited, then the gap is small and your score goes up. Consequently, you could be more content with your lot because there is little more you can climb to. The variables they’ve selected ignore competition, ambition, inventiveness, hard work. Emphasising balance, complacency, and contentment, they sidestep the competition, the ambition, and the invention that elevated our living standards during the past two centuries.”

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!