Thursday Thinkers (37/24)

As promised, here’s a collection of interesting things I saw this week earlier than usual because of the day before AFL grand final day public holiday (how is that even a thing, Victoria?). Normal service will resume on Monday.

Roll out the scapegoats

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is taking Coles and Woolworths to court, alleging that the two supermarkets would raise prices, only to cut them later and claim it’s a “discount”:

“Following many years of marketing campaigns by Woolworths and Coles, Australian consumers have come to understand that the ‘Prices Dropped’ and ‘Down Down’ promotions relate to a sustained reduction in the regular prices of supermarket products. However, in the case of these products, we allege the new ‘Prices Dropped’ and ‘Down Down’ promotional prices were actually higher than, or the same as, the previous regular price”

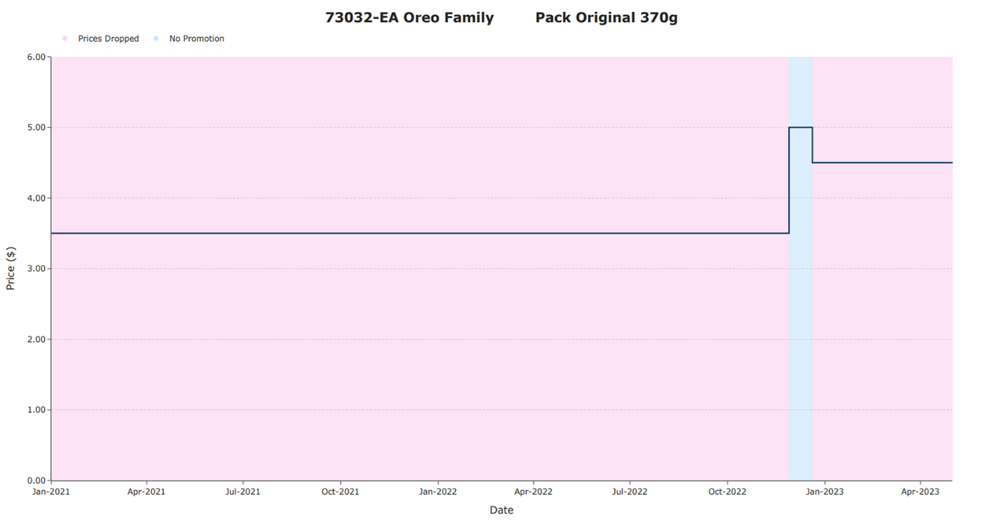

I’m not going to pretend I know why grocery stores raise – an example used was for Oreo’s – only to cut them again shortly thereafter.

Prices change for lots of reasons, and supermarkets have various strategies to maximise revenue, e.g. loss-leaders, that makes any kind of price-only analysis impossible without first knowing everything about supply, demand and strategy. But what I do know is that prices were unchanged for a long time: at least two years, according to the ACCC’s chart. So, either it’s blatant gouging by the supermarkets, or it’s complicated because pricing is a discovery process that depends on many factors.

For example, say that consumer demand for Oreo’s starts rising – perhaps because of an unexpected surge of inflation – so in response the supermarkets raise prices both to ration supply and because their costs are increasing. If they overshoot the mark, observed demand falls off and so prices are cut, sacrificing a bit of margin for higher volumes (supermarkets don’t maximise revenue from just by raising prices, but by optimising price * quantity).

Then the marketing team gets involved and sells it as a “price drop”, which appears to be what the ACCC is calling price gouging. But there is another possibility: these pricing shenanigans may have happened because unexpected inflation and the pandemic’s supply disruptions – neither of which affect all goods and services evenly – really shook up the industry, and so the supermarkets had to re-discover a lot of prices in a really short amount of time.

If that’s the case, then it may well be consumers who the ACCC is hurting the most with this action: supermarkets will still raise prices to preserve margins when demand is strong or cost pressures increase, but they won’t as willingly correct their mistakes in the other direction for fear of the regulatory repercussions. Getting to the market-clearing price will either take longer with small, regular increments (risking shortages of certain products), or overshoot the mark until inflation erodes the difference away over time. In either scenario, there will be fewer gains from trade and an overall welfare loss for Australians. In economic jargon, efficiency falls and so the producer and consumer surplus decline because of the deadweight loss imposed by the ACCC.

The fundamental problem with the ACCC’s accusations is that without some kind of smoking gun (e.g. a price gouging collusion email or something), no one can know what the ‘correct’ price should be without first knowing demand and supply. Economists have understood that since at least Alfred Marshall (1890), who said that there are a “multitude of influences” that determine the difference between costs and prices:

“[W]hen a thing already made has to be sold, the price which people will be willing to pay for it will be governed by their desire to have it, together with the amount they can afford to spend on it. Their desire to have it depends partly on the chance that, if they do not buy it, they will be able to get another thing like it at as low a price.”

In the short run price is determined by demand, and demand increased a lot between 2021-2023, so for me that’s the more likely culprit than some sudden discovery of greed and price gouging in a sector with relatively small profit margins that remained flat over the period in question.

Enter Albo

But this goes deeper than just the ACCC’s potential misunderstanding of basic economics. Never ones to waste a crisis, the government was quick to praise the ACCC’s action and use its accusations to blame supermarkets for inflation. Here’s Albo:

“When you’re charging more for products than you should, it of course has an inflationary impact by definition.”

That’s actually not the definition of inflation, which is a fall in the purchasing value of money. Supermarkets “charging more for products” does nothing to affect the value of money relative to goods; it only changes relative prices. Higher food prices might increase measured inflation in the short run because other prices can be sticky and the basket of goods used to estimate inflation isn’t updated all that frequently. If people are spending more on food, then they must be spending less on everything else, unless the value of money relative to goods has declined (e.g. due to inappropriate monetary or fiscal policy). But higher supermarket prices alone tell us nothing about inflation – never reason from a price change!

I’m reminded of the 1970s, when everything from anchovies to oil was blamed for inflation:

“When US oil prices quadrupled following the OPEC oil embargo in the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, [Fed chair Arthus] Burns argued that, since this had nothing to do with monetary policy, the Fed should exclude oil and energy-related products (such as home heating oil and electricity) from the consumer price index.

…

Then came surging food prices, which Burns surmised in 1973 were traceable to unusual weather – specifically, an El Niño event that had decimated Peruvian anchovies in 1972. He insisted that this was the source of rising fertiliser and feedstock prices, in turn driving up beef, poultry, and pork prices.”

Inflation is caused by too many dollars (demand) chasing a given amount of goods and services (supply). We’re just coming out of a period of excess demand, which can be caused by a demand or supply shock:

“If prices and quantities are both increasing, it’s demand that’s driving the price change. If prices are rising while quantities are declining, something on the supply side is changing. Politicians can pin the rising prices of gas and turkey on supply-chain issues, corporate greed, or anti-competitive behaviour all they want. But since prices are rising across the board alongside increases in production, an increase in overall consumer demand seems to be a bigger driver. That’s not something that demagoguery will do anything to solve.”

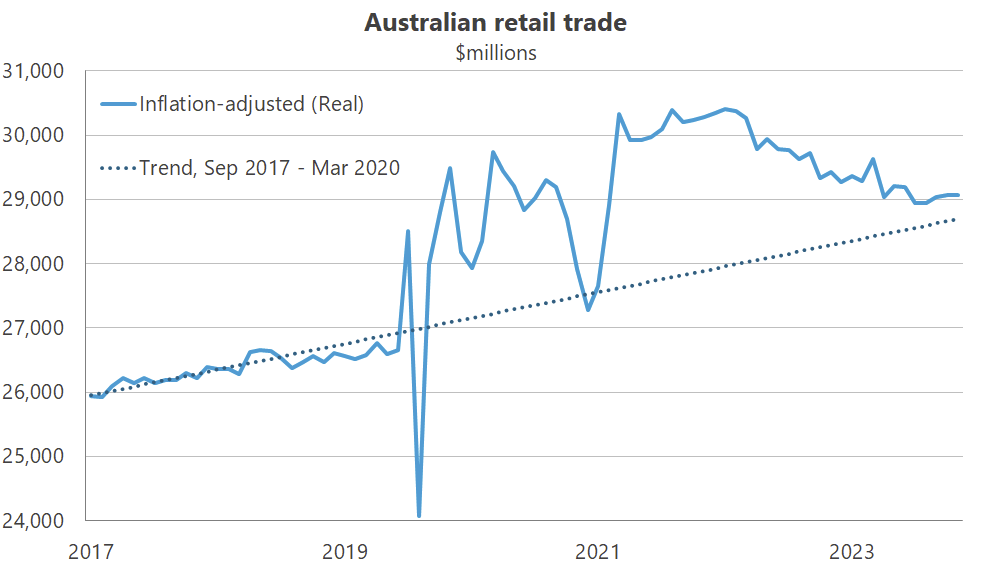

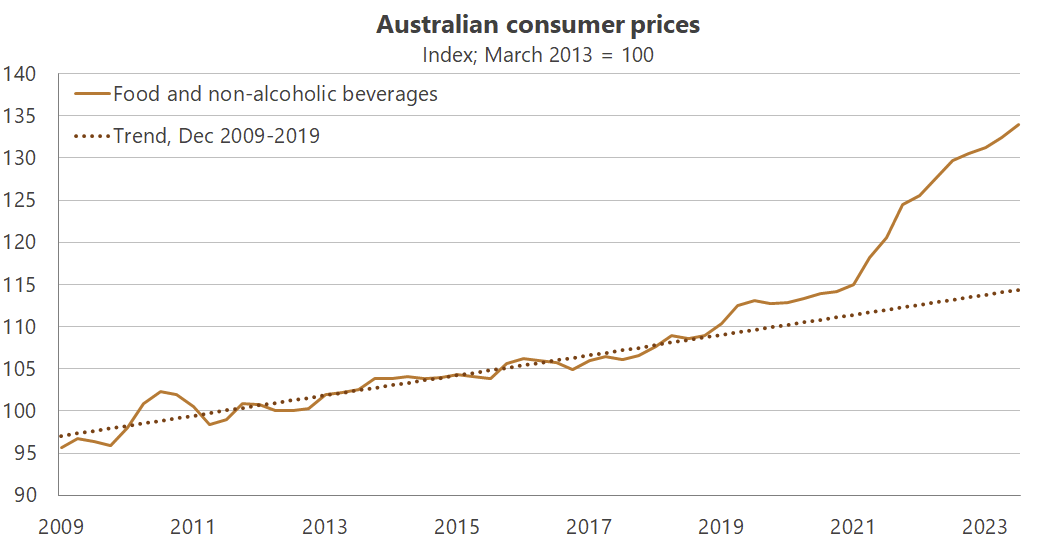

Woolworths and Coles didn’t suddenly get greedy in 2022-23. It’s not possible to “gouge” consumers with higher prices without also reducing quantity demanded unless those consumers have acquired more dollars to pay those higher prices. In Australia, prices and quantities of food increased after the pandemic:

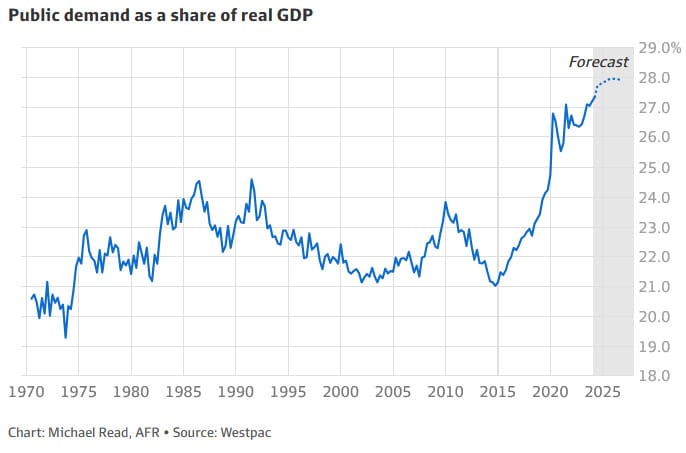

The cause of higher food (and other) prices was an increase in demand fuelled by monetary and fiscal policy, and the only people to blame work(ed) in Parliament House and Martin Place. Albo is trying to deflect attention away from his own government, which is spending more as a share of GDP than any government in Australia’s history:

If Albo is looking for someone to blame for inflation persisting this long, he need only look in the mirror.

Don’t underestimate AI

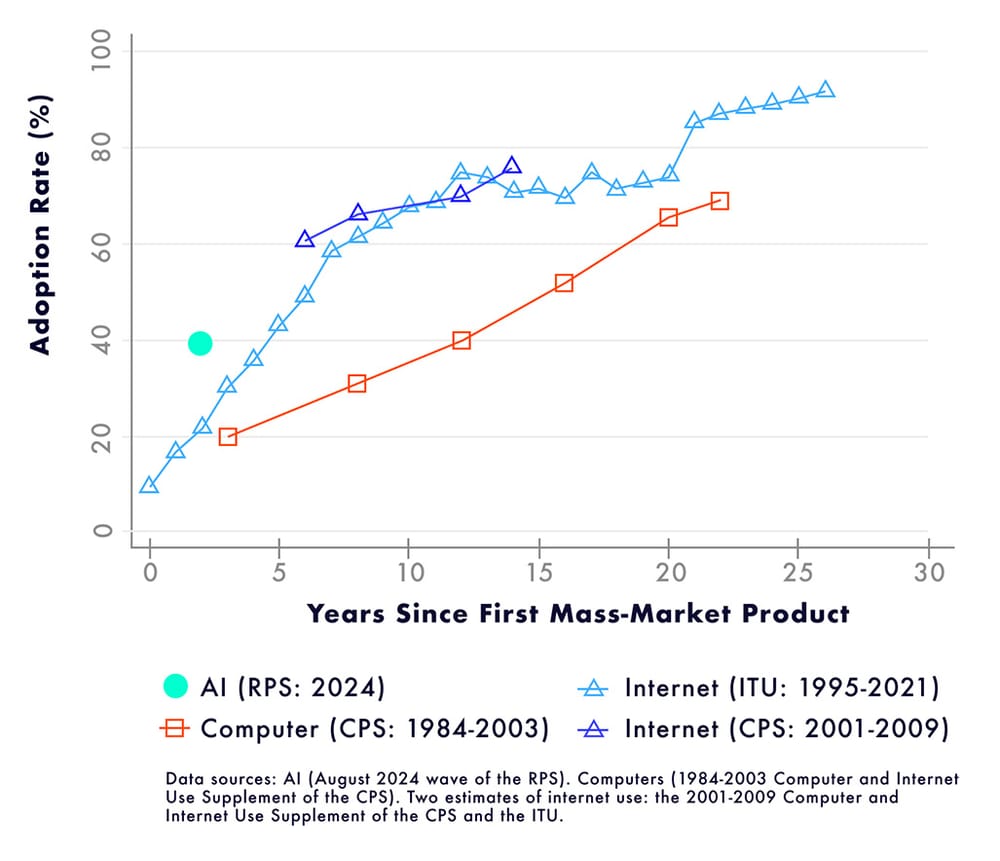

Regular readers know that I don’t think we’re even on the road to artificial general intelligence, and so many of the doomers are wasting their energy. But that doesn’t mean what we call artificial intelligence – large language models, or LLMs – aren’t going to have an impact. A new paper from Harvard researchers found that the LLM rate of adoption has surpassed the personal computer and internet:

And it’s not just coders and data scientists using it:

“Nearly half of those in computer, mathematical, and management roles use it, as do one in five blue-collar workers. Respondents indicated that generative AI was useful for a variety of job tasks, such as writing, administrative support, interpreting and summarising text or data, and coding, with over 25 percent using it for each of the tasks listed.”

LLMs work on top of computers and the internet, so it makes sense that they’d be adopted at a faster rate – the legwork was already done.

But just because people are using them, doesn’t mean they’re going to have an impact on productivity. A computer by itself is rather useless; you need the suite of programs and connectivity of the internet to make use of it.

So, the billion dollar question is: what will people build on top of LLMs, if anything? Lots of countries – including Australia – are in somewhat of a productivity crisis, so our ability to diffuse whatever emerges could go someway to boosting real wages for the next generation. That, or it’ll end up in the dustbin of history like so many other promising innovations.

Zoning is to blame

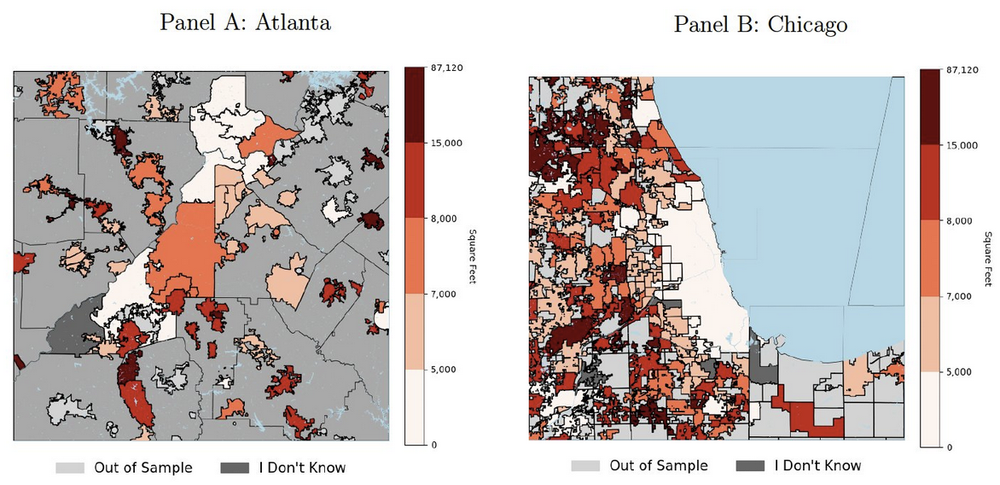

While on the topic of LLMs, a new paper looked at how housing regulations affect housing construction in the US (the code and data were also made available, which is very cool):

“[W]e establish five facts about American zoning: (1) Housing production disproportionately happens in unincorporated areas without municipal zoning codes. (2) Density in the form of multifamily apartments and small lot single family homes is broadly limited. (3) Zoning follows a monocentric pattern with regional variations, with suburban regulations particularly strict in the Northeast. (4) Housing regulations can be clustered into two main principal components, the first of which corresponds to housing complexity and can be interpreted as extracting value in high demand environments. (5) The second principal component associates with exclusionary zoning.”

TL;DR, because of zoning most new construction happens not close to jobs and amenities but out in exurban developments where there are fewer restrictions (e.g. frontage, minimum lot size requirements, public hearing requirements). What was especially interesting is that different regions use different strategies to achieve the goal of preventing construction. For example, while California doesn’t utilise bulk zoning as much as cities in the North-East, it instead prevents construction with “process”.

Anyone looking at how to increase housing affordability needs to know how each specific city (or suburb!) regulates housing supply. Here’s a map comparing minimum residential lot sizes in Atlanta and Chicago:

A consequence of these restrictions – other than less affordable housing, of course – is a lack of density in well-located suburbs, limiting the ability of lower income people from moving in and divides society by income and race. Getting housing right is very important (it can even lift much-needed productivity growth!).

Toward the dustbin of history

China is an interesting country. It has a strong central government, but a lot of the spending is done by local governments – specifically, through local government financing vehicles (LGFV).

Many of China’s problems today come from past decisions made by LGFVs (fully supported and incentivised by the central government, of course). So I read with interest when, in a recent essay, Jon Sine got stuck into the rise and fall of these things. It all started when China liberalised:

“When China began allowing markets after Mao, the economic structure shifted beneath Beijing’s feet. SOEs crumbled, the tax base eroded, and tax evasion increased. Total government revenue and the center’s revenue share massively declined.

…

In the early 1990s Beijing sought to re-affirm central authority. One of the more reliable ways to do so is to take control of the purse. Of this view were General Secretary Jiang Zemin and his Premier Zhu Rongji, who pushed forward a major fiscal and tax restructuring in 1994. Two big changes were wrought. First, Beijing decisively centralised revenues while keeping expenditures decentralised. Second, Beijing barred local governments from running deficits, and from borrowing. China, the most fiscally decentralised country in the world in terms of local expenditure share, overnight developed a stark vertical fiscal imbalance, with unfunded mandates at the local level. Nearly an inversion of the original problem. But Beijing was happy and that’s what mattered (to Beijing).”

While Beijing sends almost all of its revenue back out to local government, it works slowly and “a year or more can pass” before those funds get from the top to the bottom (after plenty of leakage along the way). As a result, the bottom – local governments – often face a very real resource gap between what they’ve been told to spend and what they actually have to spend:

“[L]ocal governments needed a new financing tool. Given the enormity of the task, no typical fiscal revenue stream would suffice. That’s where a little ingenuity from financial big whigs at China Development Bank (CBD) came in to play. Chen Yuan, son of famed Chen Yun and then head of CBD, helped local officials in Anhui and Wuhu concoct a simple but brilliant way to expand their economic footprint: create a corporate entity owned by, though at arms length from, local governments that could borrow unconstrained by the 1994 budget and regulatory regime. The entity’s raison d’etre was simple: (1) raise money and (2) build infrastructure.”

The whole thing went into “into steroidal overdrive” after the Great Recession, with Beijing directing local governments to borrow for countercyclical infrastructural stimulus. But as the bad debts piled up, Beijing started to crack down on the “weakly institutionalised, moral hazard laden system”. No one knows how bad the situation really is – from 2018, Beijing ceased making various regulatory documents public – but it’s definitely a problem:

“LGFV’s financial situation is, to put it frankly, very bad. In aggregate, earnings (before interest, taxes, and depreciation, i.e., EBITDA) do not cover even their interest payments. Including government subsidies only occasionally pushes the interest coverage ratio above one. Moreover, the average borrowing cost for LGFVs, 5% or so, far outpaces their 1% return on assets, posing obvious sustainability problems.”

That’s generally what happens when you borrow to build a bunch of cities that no one wants to live in and construct bridges to nowhere. How China cleans it up remains to be seen, but it would appear the days of LGFV’s driving “growth” through land-financed investment is over:

“At least one implication is clear: the land-finance system that for the last two decades has been the lynchpin for much of China’s development is being directed toward the dustbin of history. High-powered top-down incentives to boost growth are no longer so high-powered. Property developers have taken their hit, but LGFVs remain at large.”

China’s central bank just “cut a key short-term interest rate and announced plans to reduce the amount of money banks must hold in reserve to the lowest level since at least 2018”. That might help take some of the immediate pressure off the economy (iron ore prices certainly responded well), but only Beijing can address the structural problems caused by decades of LGFV mischief.

Fun Fact

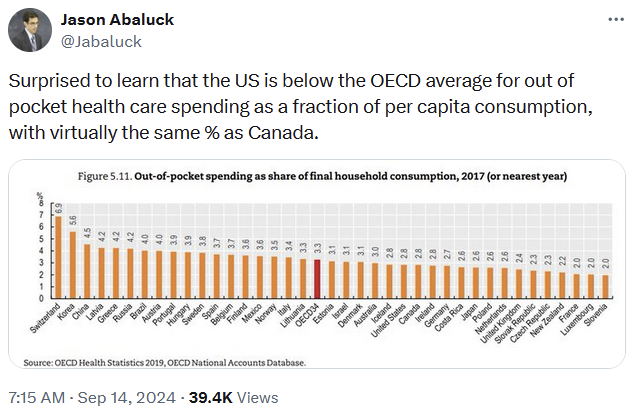

The US spends nearly three times as much per capita on health care than the OECD average (Australia spends about 20% more). But Australians and Americans don’t come close to personally feeling the true cost when using it:

In the US, a lot of health spending done by employer-provided insurance, which is problematic not just because it dulls price signals, but because it’s regressive (benefits high earners more) and can tether people to jobs, stifling labour mobility and job market matching. It exists because it’s very tax effective for both the employer and employee.

In many other OECD countries – including Australia – most health care spending is funded by taxpayers. Either way, there’s not a single OECD country that spends more than 7% out of pocket for health care. Even Singapore (not an OECD country), where over half of all health care spending was out of pocket as recently as 2005, now only pays about 20% out of pocket.

People don’t like paying for health care and politicians are happy to oblige by hiding the true cost across all taxpayers.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!