Thursday Thinkers (42/24)

Just a heads up that I’m going to be in Japan all next week. I’ve got a couple of post ideas lined up but I’m not sure how much writing I’ll be able to get done while trekking across Kyushu.

Also, I’m planning to send out a reader survey at some point, so please keep your eye out for that one – I’d love to know what you think about Aussienomics and how I might improve it!

On to this week’s news, starting with the US election (what else!).

The dust has settled

It turns out that the US Presidential election wasn’t that close after all: Donald Trump has comfortably secured himself a second term, and will be sworn in on 20 January 2025.

Trust markets, not polls!

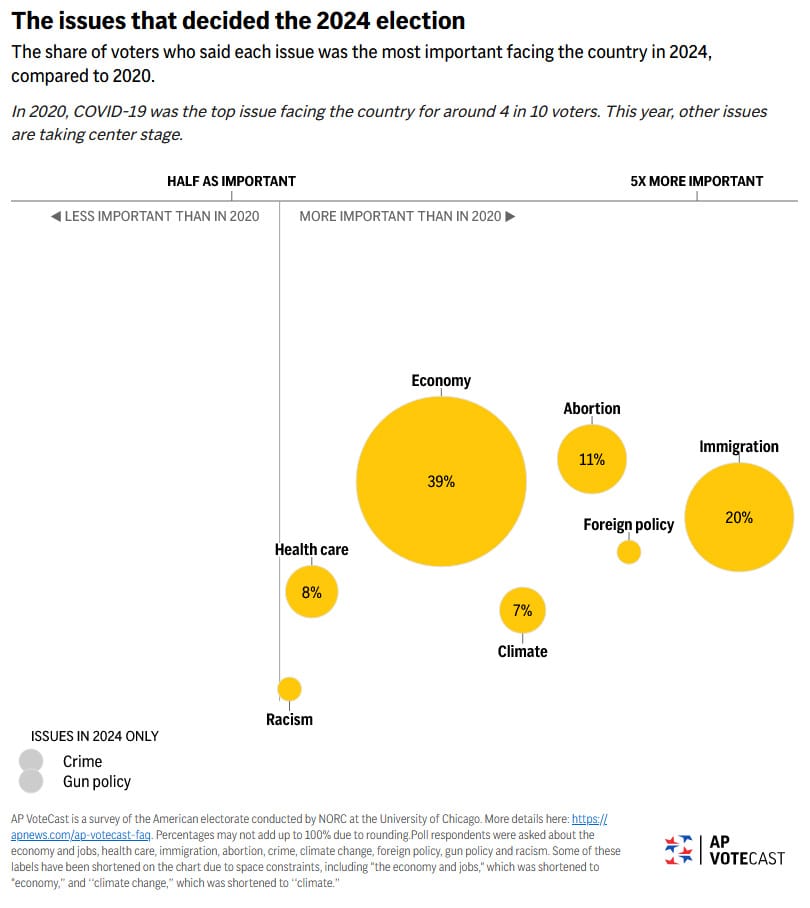

The result has big implications for Australia. First, people really hate inflation and are easily riled up by stories about uncontrolled immigration:

Both are also major issues in Australia. In his Budget reply back in May, opposition leader Peter Dutton mentioned inflation and migrants nearly a dozen times each. And he was right to do so, if a new McKinnon Poll is to be believed:

“It found 46% of Australians prioritise keeping inflation low, while just 12% believe keeping unemployment low should be the priority.”

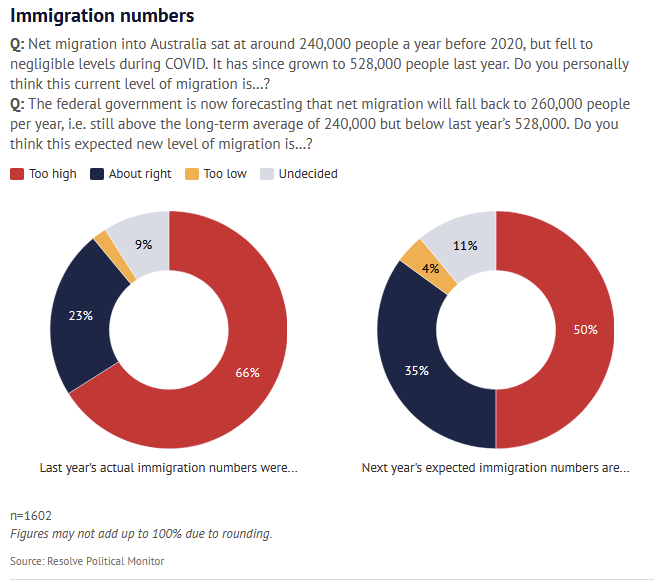

Most also believe that the current rate of migration is too high:

For voters, causation is irrelevant. Did the Albanese government cause the inflation? No. But it certainly hasn’t done anything to make it better: pro-cyclical policy during in an inflationary crisis is precisely the wrong thing to do!

Come the election, all that will matter is whether voters think the Albanese government will be able to fix these key issues. If not, then they’ll ‘kick the bums out’, just as the Americans kicked the Democrats out.

As for Trump’s economic policies, he’s a man whose views on many issues are Lyndon LaRouche-esc, i.e. grounded more in feels than empiricism. It’s one reason why he’s so keen on tariffs, despite the theoretical and empirical evidence showing that they harm both consumers and the producers they’re claiming to protect:

“Overall, the negative effects of higher input costs and reduced exports outweighed any benefits from import protection for manufacturers as a group.

…

Consumers are also hurt in ways less obvious than higher prices. For example, tariffs also reduce their options when they shop. Go into any grocery store today at any point of the year, and you will see a dozen kinds of fresh fruit. How? Modern trade. Consumers benefit from this variety instead of being stuck with canned peaches all winter.”

Trump also holds a litany of other poor policy beliefs that could be more damaging this time around, if he’s able to act on them (which is no certainty):

“The first iteration of Trumponomics was lucky enough to be implemented during a period of high growth and low inflation. Its next incarnation would not only be adopted in less benign circumstances, but would also itself be of a much more disruptive nature. His campaign is proposing a second, much bigger hike in tariffs, lavish tax cuts, a labour-supply shock in the form of mass deportations and attacks on the independence of the Federal Reserve.”

Trump’s policies are likely to raise real interest rates, which means the US Federal Reserve will have to keep nominal rates higher than otherwise, or allow inflation to ratchet back up. It’s no surprise that long term bond yields surged – including in Australia – as it became clear that Trump would win, with expectations adjusting accordingly.

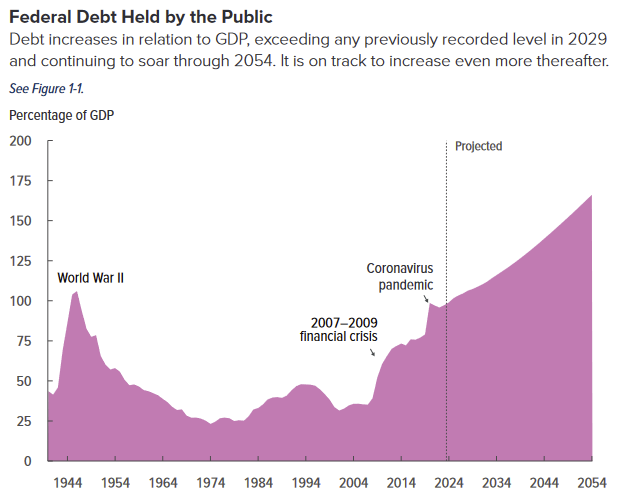

Like Biden and Harris, Trump also has no plan to address the elephant in the room: government debt. Well, unless you consider this to be a plan:

“Maybe we’ll pay off the $35 trillion US debt in Crypto. I’ll write on a little piece of paper ‘$35T crypto we have no debt.’ That’s what I like.”

The current US fiscal path is clearly unsustainable, even assuming no future shock, recession, or other reason for politicians to spend more than is currently budgeted:

At some point there’s likely to be a spike in interest rates – a Liz Truss moment – that forces a President and Congress to pro-actively address the debt. But as Scott Buchanan recently observed, until that happens more debt is likely to be a positive for markets, because a lot of US government deficit spending tends to flow straight to corporate earnings, boosting stock prices.

Enjoy it while you can!

‘Tis the season

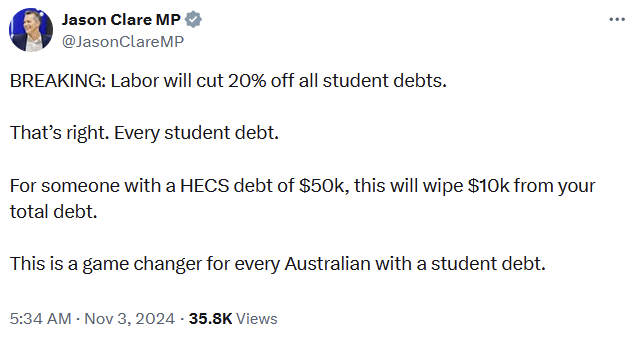

How do you know there’s a federal election coming up? The policy announcements get an order of magnitude stupider than usual. Like this from the Albanese government:

I don’t mind higher repayment income thresholds, which is also part of this policy package, even if Clare didn’t mention it. Raising them probably won’t even affect the fiscal situation all that much; maybe the average debt is paid off a few years later. Big deal.

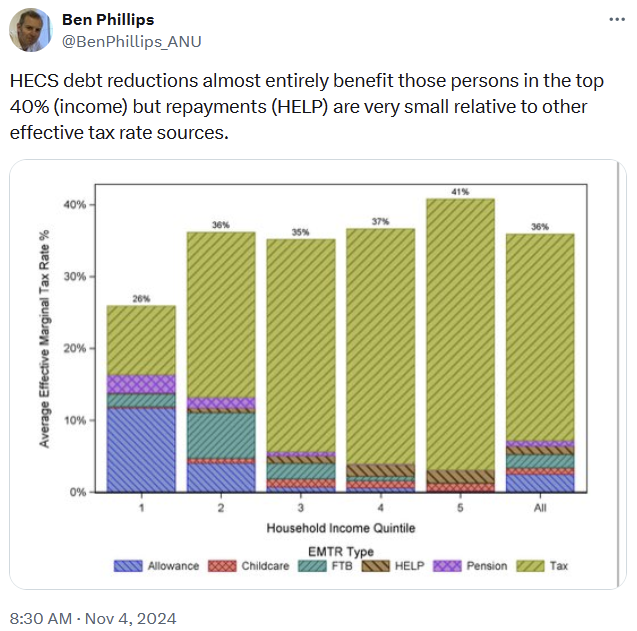

But cutting HECS debt is straight up a bad idea. It’s basically more than $11 billion worth of vote-buying welfare for those who least need it, given that people with HECS debt earn much more income over their lifetimes than those who never go to university.

It also won’t do anything about the cost of living. HECS is not a loan. It’s repaid based on a person’s income, not the size of their debt. Cutting 20% of the debt will only affect when the repayments end, not how large they are. The only thing this will do is increase borrowing capacity – so, more demand stimulus on the housing fire. Fantastic.

What about the incentives? Course fees – which is what HECS covers – aren’t even a barrier to attending university in Australia, given no payments are required to be made until people actually earn a certain income, it’s interest free, and ramps up progressively. Something like 25% of all HECS debt is never repaid because of this feature.

As for trade-offs, the government’s spending on this will come at the expense of spending that could have been used to assist genuinely poor people, or just not taxed away from non-graduates and those that have already paid off their debt in the first place.

It’s just really, really bad policy and shows that the Labor party doesn’t even pretend to represent the working class these days, but is instead competing with the Greens for the votes of inner city elites (the Greens, by the way, fully support this policy).

It almost feels as if we’re belatedly shifting in the same direction as the two major US parties, where the Democrats now represent the university educated, inner city types, and the Republicans the more traditionally blue collar ‘flyover’ states.

Basically, the opposite to how people voted back in the 1960s.

I also think that undermining the fiscal sustainability of HECS raises another issue: namely, that the federal government should start to move some of its “investments”, like HECS and the NBN, back onto its balance sheet. They’re not even pretending that these will ever pay for themselves anymore – who in their right mind will pay their HECS off early when uncle Albo will probably be back with more soon enough? – so being able to hide the losses from the public is just pure political deception.

I’d also argue that things like the Future Made in Australia slush fund should be moved onto the balance sheet, although I suppose it’s still early enough that there’s a small chance some of it isn’t worthless. Nonetheless, the tendency for more and more government policy to be classified as an “investment” and hidden from the voters is a disturbing trend that started long before the Albanese government and needs to stop (where are the ’ transparent’ Teals when you need them?).

How big should the government be?

Australia, for a brief moment, had a target to limit government spending (state and federal) to 23.9% of GDP. It’s now closer to 30%.

But is a bigger government inevitable, because of the phenomenon known as Baumol’s (cost) disease? Philippe Lemoine recently wrote an interesting essay about that question:

“The kind of services provided by the government also have low productivity growth, so even if waste and mismanagement in the public sector doesn’t increase, we should expect their relative cost to rise. In general, because of inflation, $100 today will get you less goods and services than $100 in 1950. But the prices of different goods and services don’t rise at the same rate and, in particular, Baumol’s cost disease implies that the prices of services in general and government-provided services in particular will rise faster than prices in general. In other words, even adjusted for overall inflation, the same dollar will get you less public services today than it did in 1950.

…

[T]his means that, to maintain the volume of public services per capita at the same level, it wouldn’t have been enough to keep public spending at the same level adjusted for overall inflation. Government spending per capita would have had to increase faster than overall inflation or the volume of public services per capita would have gone down. If that didn’t in fact happen, then Baumol’s cost disease would be a likely culprit for the decline of public services that people complain about.”

The only problem with that argument – which was recently made by a former World Bank economist – is that forgets that the denominator, GDP per capita, has also increased significantly:

“In turn, the fact that Americans are much richer means that, other things being equal, they can get the same amount of public services with public expenditures that are much smaller as a share of GDP.

…

Of course, other things are not equal, because due to Baumol’s cost disease the prices of government-provided services have increased a lot relative to other goods and services and in theory this could have more than compensated for the fact that GDP per capita has increased. So the question is whether the share of public spending in GDP has decreased enough or the prices of government-provided services have increased enough relative to the prices of other goods and services to make the volume of public services per capita go down between 1950 and 2023.”

Lemoine does the calculation and found that cost disease grew much more slowly than GDP since 1950, to the extent that the government is now able to buy or produce around 2.6x as many goods and services with the same amount of spending, as a share of GDP, as it did in 1950.

Basically, the size of government is much bigger today in absolute and relative terms than it was in 1950, because we’re a lot richer and so can afford more of it. In my view that means there’s a good case for fiscal rules that limit government spending as a share of GDP, preserving the more productive private sector’s share, if only to ensure that GDP per capita can continue to grow faster than Baumol’s cost disease.

Australia’s tobacco and vape wars

One of the first posts I wrote on this site was about vaping. Specifically, the likely unintended consequences of the government’s crackdown on them, one of which was to increase the demand for tobacco:

“At the margin, higher prices (time and cost) and a decline in quality (fewer options) could force people onto what looks set to be a lucrative black market, as it has done for cigarettes.”

Guess what happened? World-leading taxes on tobacco and the restriction on vapes – a substitute for cigarettes – has seen a huge black market emerge, sparking “what police believe is a turf war between organised crime groups”:

“In July, tobacco company Philip Morris, which has its own commercial interest in a crackdown on the trade, told a Victorian inquiry it believed the tobacco black market was considerably larger than has been estimated by the ATO.

Instead, it said, the illicit market ‘accounts for over 28.6% of overall tobacco sales in Australia’.

Meanwhile, a Therapeutic Goods Administration report examined by a Senate inquiry this year heard that as many as 97% of users were estimated to be buying their vapes from the black market, estimating the trade to be ‘worth well over $400m million annually’.”

The real winners from the vape crackdown have been local gangs and criminal enterprises, who have a lucrative new product they can sell to fund their activities.

Smokers and vapers – usually hailing from the most disadvantaged parts of society – are punished, either through a highly regressive tax that does little to stop them smoking, or forces them onto the risky and uncertain black market.

If the government wants to reduce smoking and vaping, it needs to ensure that the benefits of its policy (harm reduction) exceed the costs (e.g. rising crime, imposition on smokers). In this case, it looks to have achieved the opposite.

AI won’t take your job

Well, it won’t take all the jobs. And it will create many new better jobs, too:

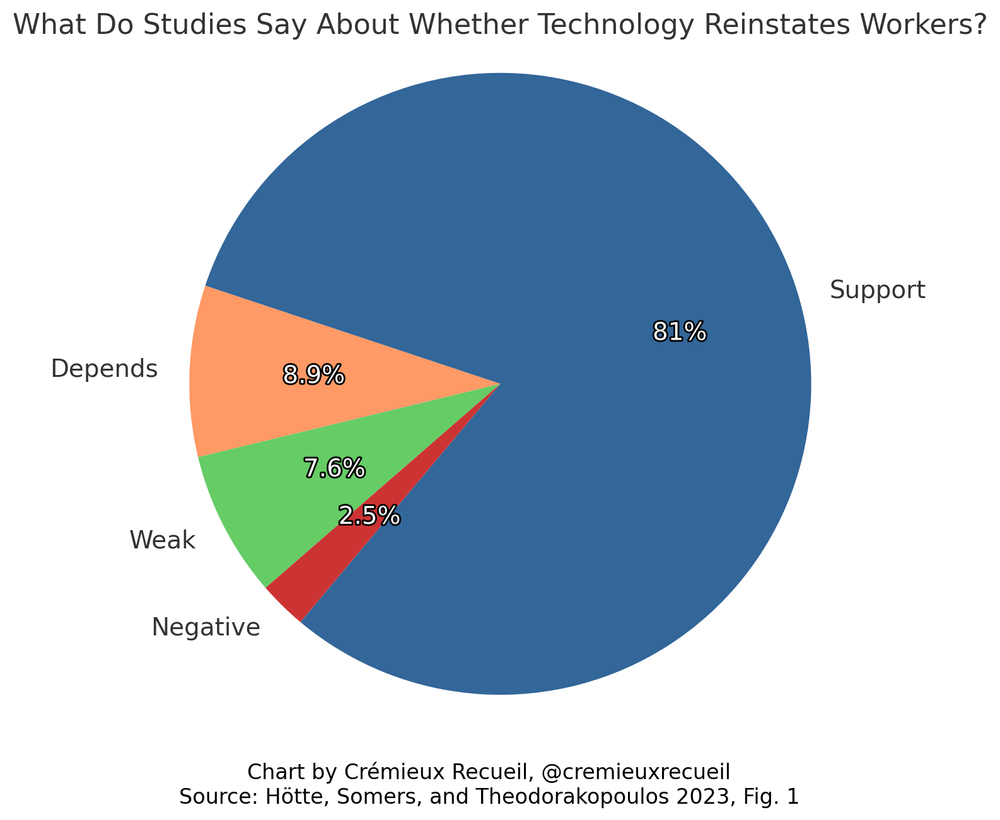

“When technology replaces workers, it does so by saving costs and potentially increasing productivity, ultimately stimulating the demand for labour. To that end, we should also expect technology to reinstate workers. Across 79 studies, there’s overwhelming agreement about the existence of a reinstatement effect:”

That’s from the excellent Cremieux Recueil, who spends a lot of time refuting the claims of a looming technology-induced jobs crisis made by recent Nobel laureate Daron Acemoglu, whose assumptions often tend to lead him astray in his more recent work.

One example of how AI could change the nature of work might be coders shifting from writing code themselves to prompting AI to do the tedious finger-work. For example, Google has already reported that “a quarter of all new code at Google is generated by AI, then reviewed and accepted by engineers”.

The biggest benefits are likely to accrue to “individuals with relatively lower ability”, which would reduce inequality – precisely the opposite of what people like Acemoglu are worried about!

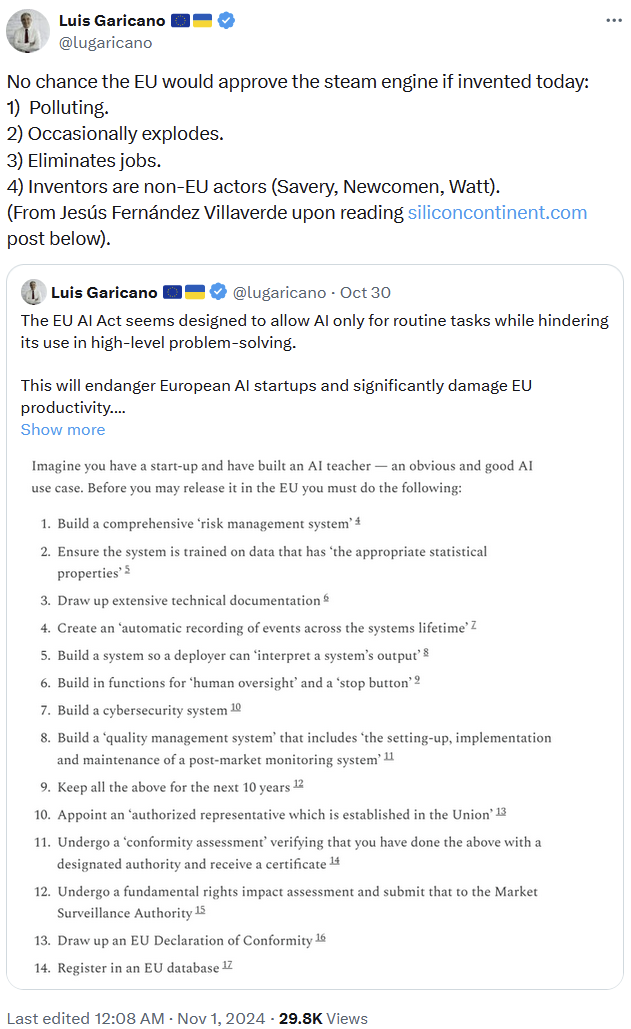

In my view, the single biggest risk is that regulators listen to people like Acemoglu and allow themselves to be captured by naive ‘doomers’ and the leading AI companies, which would kneecap one of the most promising productivity-enhancing innovations we’ve seen for decades.

For a window into what that future might look like, here’s the European Union’s approach:

“An AI bank teller needs two humans to monitor it. A model safely released months ago is a systemic risk. A start-up trying to build an AI tutor must produce impact assessments, certificates, risk management systems, lifelong monitoring, undergo auditing and more. Governing this will be at least 50 different authorities. Welcome to the EU AI Act.”

AI companies know they have no moat, which is why they’re trying to scare politicians who don’t understand large language models into passing “urgent… risk prevention” regulation in “the next eighteen months”.

That such regulation would also eliminate future competition and cement their position as market leaders is just an unfortunate coincidence, I’m sure (but Claude knows!).

Fun fact

Why do European nations stagnate once they’ve caught up to the frontier? Because the European Union actively fights against change:

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!